-

Posts

2,273 -

Joined

-

Days Won

502

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

Logic of Shadows Doing a little research into the aesthetic of Film Noir last night we watched Jeanne Eagels (1957) with Kim Novak. I was drawn to it because it was in a list of Noir genre busting Film Noir films, in a critical essay list that included 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was filled with beautiful frames. But this series below just captured my brain. Kim Novak, caught in emotional desperation, turns her face away from an old flame who has come to save her from self-destruction. I'm just mesmerized by her turn-away, how she suddenly incandesces in almost a blownout white of sun, as she turns away, despondent. The Logic of Shadows. Here she is "going away", but growing brighter, which in just a few frames enacts her tragic arc as a character in the film, a kind of Icarus of morality. Catching more light, but burning up. It shows that even in a simple binary of light and dark you can compose a calculus of great meaning.

-

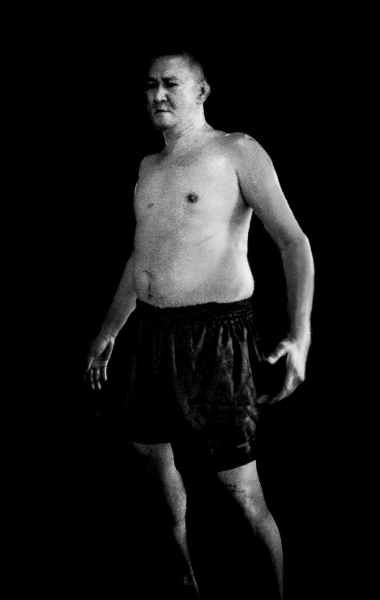

Unfortunately, this one didn't work out all that well! We got Dieselnoi to set it up, and he came with us and we all sat down and had a conversation, chatted old times, but Vichannoi was not in a place where he wanted to do any instruction. He's gained a fair amount of weight, and seems like a super successful businessman. So, we didn't push it, and instead and a nice talk. Not every effort to film works out!

-

In general, I think it's pretty good practice to learn to get comfortable throwing techniques higher because it kind of moves your baseline. When you get stressed, your teep might lose elevation. If you are used to throwing higher teeps mid-teeps will feel easier. As to ideal teeping height, this is the way the Dieselnoi explained it, if I recall. If facing a puncher, teep high. If facing a kicker, teep mid (controlling the hips).

-

The first thing is probably doing 100s of teeps each day, just to get more and more comfortable with the elementary action. As you get more habituated you become both more grounded (balanced) and quicker too. The second thing is to learn to pull that teep back after contact, a little like the jab is pulled back. Your teep is like a jab, its not a power shot, and all power comes from the body weight transfer, so getting the feeling of that little "pop" will just improve over time. Pretty awesome that you are listening to the Muay Thai Bones podcast! If you keep having trouble with your teep being caught, one thing to do to get a partner every day and have them hold your teep, and work on your balance and counters to the catch. A quick turn of your leg "in", with the knee turning to point toward the floor, should free almost any catch, if you do it quickly. You can also do a "heavy leg" counter, which is you just lean forward and just weight the leg directly downward, while it remains straight. It's surprisingly effective, most do not prepare for that weight transfer. And lastly, you might be more comfortable with more of a side on teep, like the one favored by Samart at times. A straight on teep gives your heel to the opponent, as a handle to cup from below. If you teep quickly it shouldn't be a problem, but turning the foot with a side angle removes this handle. You can see Samart using his side teep in this fight: Just a few thoughts. If anyone is wondering about the podcast in question, here is the episode, we talk about the teep in the first segment:

-

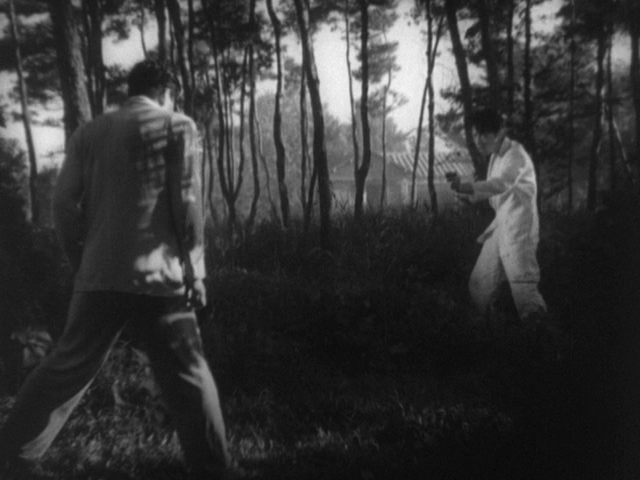

In terms of personal inspiration again, Kurasawa all the way. I've read that there is some debate about how many of his films would qualify as Film Noir (some fancy a very narrow boundary), but a film like Stray Dog (1949) definitely fits the bill, and is incredible. For my part, a great number of Kurasawa films are quite Noir, so many of them in the aftermath of a disillusionment in society. This is leaving aside for a moment his Samurai films, which may be one of the more important templates for a Muay Noir photography. Kurasawa is a director who sometimes slips from my mind despite having enormous impact on me, visually, and when I go back to him I shake my head and think to myself: There may never have been as great a director as him. Stray Dog

-

More on classic Film Noir aesthetics, from Paul Schrader's - Notes on Film Noir Most interesting in these observations to me is #3, that the subject and the context are given the same lighting. I experience Noir as plucking out the subject from the darkness, with the avenue of light, while I can definitely see what Schrader is saying. This is maybe a fundamental tension of a subject swallowed up by the corrupting or oeneric world, and the subject disjoined from it. Maybe there is a passing into and out of existence, between these two poles. I have to think on this.

-

I'm still thinking about your questions about performativity and femininity. There is really a perfomative aspect of Film Noir and also in Muay Thai, and there is a hyper-masculinity in both, but I'm not quite sure how they connect up. We get that line of Dorothy Parker's "Scratch an actor, you find an actress". The Film Noir construct seems to be pretty bulwarked against any such revelation, even if true. In some ways the performative elements of masculinity are the essence of masculinity, especially when we climb out of western sensibilities. The Samurai, highly performative. The executioner.

-

On the history of Noir. In this essay on the Noir found in the 1955 film Night of the Hunter, it is argued that while Americans may have created the classic Film Noir genre (preceded in time by the French), it was the French who created the concept in regard to those American films. Post World War 2 French audiences suddenly were exposed - after a 5 year absence - to triple billed films in theaters, drawing together their similarities. In this way it was from the start a kind of meta-genre. Derived from German Expressionist influences, born of post-war American social critique, and then recognized and theorized by French audiences. on an alternate reading of the same history, "Paint it Black: The Family Tree of Film Noir"

-

I think a recurring, and perhaps substantive element of Film Noir is captured in the phrase: A stranger in a strange land. (Heinlein's title, but not the book, only the phrase.) There's often a disjunction in Noir photography (when it's not quotational), like being out of Time, or out of Space. You can't say that definitively that this is a requirement, but is an important thread.

-

This photo shot by lordk2 I think was a huge inspiration on me, and maybe says a lot about what Muay Noir can be. lordk2 shoots a lot in black and white, but his work really has lost me (our aesthetics diverge maybe). I really adored his much earilier Sumo wrestling series, some of the most beautiful photography of athletes I've seen. This photo is special. It contains I think to very compelling elements of what Noir photography can bring: Psychology and Structure. And I think this photo really propelled me in my own direction. I think it's important to ask what the difference between just turning a photo black and white, and bumping contrast and creating a Noir frame or exploration. I think it has to do with focus, the nature of focus, maybe. In any case this is a seminal photo. It's Sylvie fighting for a WMC world title maybe 3 weight classes up, with two incredible legends in her corner, Dieselnoi and Karuhat.

-

A personal influence, which for me touches on some of my Muay Noir project are the frames of the filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, who often is Noir-ish, or German Expression-ish. If not familiar, here is a video montage of many of his films. I'm not completely sure what Tarkovsky has to say about Noir, but he does oscillate between the dark and contrasted, and also sci-fi subjects, working around tradition.

-

Sylvie said something interesting the other day, about my Muay Noir photography. Something along the lines of, Muay Thai photography has too long been focused on the action, but you focus on the stillness. There is maybe something about the use of shadows that produces a pervading sense of stillness, and this use of dark maybe is another thing that make Noir a compelling vehicle for Muay Thai photography. It allows us to open up the moment more, to catch the glimmer of immanence. or the foundation of a quality, or a relation. I think there is something too this. Shadows can slow things down. Non-being creates a bath of calm and rest. Of course shadows can also be used to produce tension and drama, a sense of dread (the father of Film Noir, German Expressionism), but for me they work in the other direction. The provide the conditions for a certain emerging, a revelation. Or perhaps a stage setting.

-

Another photo edit by Emma (origin) There is something revolutionized about a woman working on her own image, within the Noir framework which contains a history of the spectral projection of the femme. This edit contains the reversal of the contradiction in gender, autopoetically generated. Does it mean something different for a woman to be working in Noir, in the sense that they are more working IN the constructed Looking Glass to a greater degree, and therefore able to subvert or synthesize it?

-

A segment on Plotinus and light, from the philosopher Gilles Deleuze, setting up a possible metaphysics of photography, and perhaps a Noir foundation. Noir as immanence. Why does Being complicate all beings? Because each being explicates Being. There will be a linguistic doublet here: complicate, explicate… …Why? Because this was undoubtedly the most dangerous theme. Treating God as an emanative cause can fit because there is still the distinction between cause and effect. But as immanent cause, such that we no longer know very well how to distinguish cause and effect, that is to say treating God and the creature the same, that becomes much more difficult. Immanence was above all danger. So much so that the idea of an immanent cause appears constantly in the history of philosophy, but as [something] held in check, kept at such-and-such a level of the sequence, not having value, and faced with being corrected by other moments of the sequence and the accusation of immanentism was, for every story of heresies, the fundamental accusation: you confuse God and the creature. That’s the fatal accusation. Therefore the immanent cause was constantly there, but it didn’t manage to gain a status [statut]. It had only a small place in the sequence of concepts. Spinoza arrives… …It’s with Plotinus that a pure optical world begins in philosophy. Idealities will no longer be only optical. They will be luminous, without any tactile reference. Henceforth the limit is of a completely different nature. Light scours the shadows. Does shadow form part of light? Yes, it forms a part of light and you will have a light-shadow gradation that will develop space. They are in the process of finding that deeper than space there is spatialization. Plato didn’t know [savait] of that. If you read Plato’s texts on light, like the end of book six of the Republic, and set it next to Plotinus ‘s texts, you see that several centuries had to pass between one text and the other. These nuances are necessary. It’s no longer the same world. You know [savez] it for certain before knowing why, that the manner in which Plotinus extracts the texts from Plato develops for himself a theme of pure light. This could not be so in Plato. Once again, Plato’s world was not an optical world but a tactile-optical world. The discovery of a pure light, of the sufficiency of light to constitute a world implies that, beneath space, one has discovered spatialization. This is not a Platonic idea, not even in the Timeus. - rabbit hole here

-

This is really beautiful, so many of these frames inspire me. A video essay on French Film Noir, written about here. Some elements of French noir we recognise retrospectively, looking back (as it were) from vantage point of the later, almost over-adored American version: fatalism, doomed lovers, a melancholic portrait of city life and a visual style that borrows and develops lighting effects and camera angles from German Expressionist cinema. But other elements strike us as being very different from Noir USA: the emphasis on everyday life and labour; a sharper analysis of fraught racial and cultural relations, even within the most exotic Kasbah; an earthier, sometimes infinitely more perverse sexuality; and a refusal of last-minute, happy-ending resolutions.

-

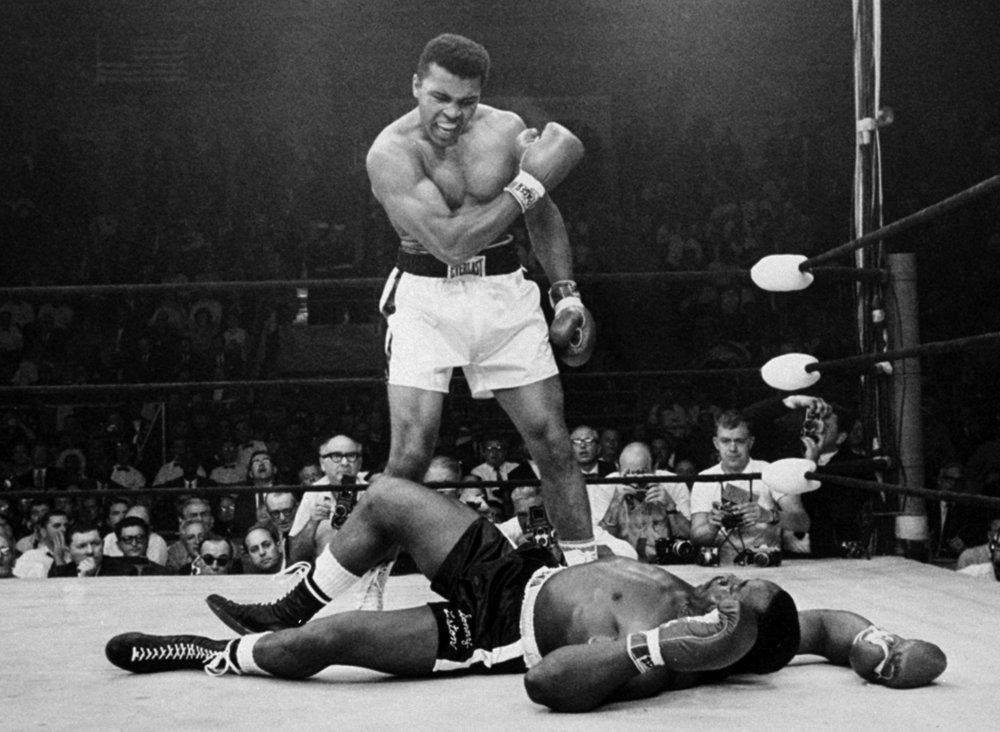

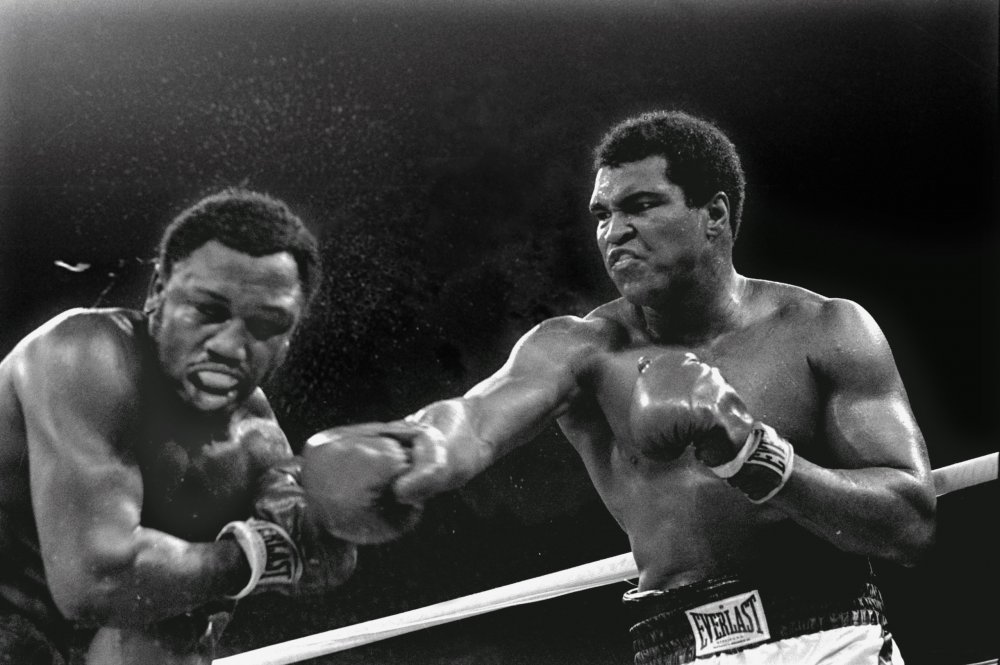

Noir Boxing References Looking at these early examples reminds us how far the genre has drifted. These are stark, simple depictions, almost atomic, and the cynicism comes through in an almost bold, ontological way. Far from the cult of cool, instead an unnerving, existential situation. Boxing sequence from Stanley Kubrick's Film Noir Killer's Kiss (1955) An increasing disorientation of angels and movement. The Set Up (1949) opening sequence: pre-fight

-

Rembrandt Light and the Metaphysics of Plotinus At least for me personally, there is an even historically older influence in the selection of Film Noir aesthetics, and even their root of German Expressionist film, and that is the very light directed painting of the Renaissance, maybe most typified by Rembrandt: And then in one of the most terribly beautiful paintings ever, Velazquez: Juan de Pareja (1606–1670) 1650 Fpr me, what is exquisite about these depictions is that the characters themselves do not contain their own light. It is as if, and in many paintings of this style, the light plucks them out from the darkness. The luminosity gives liberty or Being. This parallels the philosophy of the neo-Platonist Plotinus, who influenced the Philosophy of the day. It was Plotinus's argument that a thing only had Being (substance, reality) to the degree that it caught the light. The "light" was the illumination of the One, which shined on all things, and brought all things into Being. Not to get very esoteric, but the notion is that catching more of the light gave you substance. Turning into Being, gave you more reality. This framework is what I see in this form of lighting figures. You find this sort of theory more dynamically expressed in the 17th century philosopher Spinoza. This is where it gets more interesting, for me. Homeric descriptions, especially in the Iliad, had a somewhat Noir-ish capacity to cut-out figures of action in the world. The heroes of the epics were often reduced, or captured in the very actionability of their selves. They gained a certain reality through their ability to act. When they acted heroically this sometimes would be reflected in descriptions of their shine, their radiance, which in some sense communicated that they were catching or showing a bit of their divinity. The glinting of their selves. I think in this sense the western heroic epic holds the philosophy of Plotinus's glinting of Being (theorized centuries later). The warrior "catching light", and in that sense rising above the mortal and the mundane. I believe in some way Noir aesthetic captures of fighters, or Muay Thai, even as they partake in the aesthetics that derive from Rembrandt, communicates this transmutation, and Plontinus' argument that the more light you catch, the greater Being you have. In Homer, the hope of heroes was not only to "win", but to be sung by poets (thereby gaining a kind of immortality), catching more light in a sense. There is also the Spinozist expansion of Plotinus which is that the greater your ability to act, to move, dimensionally, the greater Being (or Reality) you had. In some ways the fighter, in the ring, is acting out some of the most primordial and essential metaphysical acts, and you could argue that a light and shadow dominant aesthetic like Noir is ideal for capturing and expressing that. I'm thinking something of these things for instance, in photos like this, where you can see the coming into Being, catching more "light" becoming extracted from the darkness.

-

Pink is definitely not a female color, at least not traditionally in the sense that we read it, boy/girl, but maybe it has some sense of flair. The Muay Femeu panache of elite starts like Samart, Karuhat and other very artful type fighters does carry with it I think some sense of the feminine, but maybe in the way that the artist, or the aristocrat has feminine overtones. With some elements of hyper-masculinity you can get transgressions into the feminine, for instance Hair Metal rock bands with scarves and mascara. I think the sense is that "I have so much masculinity, I have plenty to spare, and I'm not emasculated by these markers. The great, artful Muay Femeu masters of the age had something of that, like the singer or the movie star (as Samart was all 3). But, I'm not sure how much of that fits into Noir. I mean, Bogart definitely is counter-punctual to femininity in almost every way. Maybe as Noir became quotational we get closer to concepts of "cool" and its enactment, which then brings us more in the real of actress, pushed to the extreme maybe the masculinity of K-Pop boy bands? John Woo's intimacy between men, maybe there is something subversive to the Classic Noir structure, the way that opponents mirror and complete each other. It maybe partakes in that same sense that I had that the "opponent" holds the role of the femme fatale in the Noir universe. The alluring, and destructive other.

-

In a bizarre bit of Noir crossing, before director Martin Scorsese had produced his first hit, he approached Philip K. Dick for the rights to his Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, a year after it was published. Raging Bull would be made in 1980, Blade Runner in 1982. source Was he seeing Dick's work as a Noir film back in 1969? Godard had made the ground breaking Noir sci-fi film Alphaville in 1965. Trailer below:

-

Dana Hoey, an artist who I've had some preliminary discussion with before posting this, added this great comment on the possibilities of Muay Noir, bringing up Hong Kong Noir which is also a powerful inspiration source. If I'm not mistaken, the glorification of the hitman (maybe apexing with Meville's Le Samouraï) had a significant impact on the cultural figure of the Nakleng (gangster) in Thai culture, as cited in the Peter Vail article above (nakbun). Hong Kong cinema has exactly the quotational aspect of the hyper-cool. That's a super important point in the Muay Thai of Thailand. There is always the sense that masculinity is being performed, and that the qualities are being embodied and acted out. In the history of Noir, from Bogart on, masculinity is stylized. I think that makes another good argument why the stylization of Noir photography fits with Muay Thai portrayals. It encases stylization withing stylization, making it at home. Does Noir complicate, or produce an inordinate layer between the viewer and the Muay Thai subject? Or, does it act as a prism to clarify and focus the eye on those effort at "cool". I remember listening to Karuhat Sor. Supawan, a legend of the Golden Age, and a fighter who embodied cool, talk with Chatchai Sasakul, a WBC Champion, and also a fighter of the Golden Age. He was complaining that the Thai fighters of today no longer have charisma. Charisma was an essential component of the great fighting portrayals of the 1990s in Thailand. For him, and Chatchai who agreed, it simply was missing from contemporary Thai fighting. So, in some sense, as we add the Noir layer to Muay Thai photography we may be capturing the last bit of starlight, a vital aspect of the art, that already has dimmed in Time.

-

Especially that 2nd one, which is one of my favorite photos of yours for me. I've commented before how that metal riveting and the texture of his face create such an amazing rhyme. I also find it interesting that Classic Noir used great depth of field, but neo-Noir uses shallow depth of field (often) to further enhance the separation (alienation?) of the subject. Your is a perfect example of that isolation.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.