All Activity

- Yesterday

-

rajawaliparamakonstruksi joined the community

- Last week

-

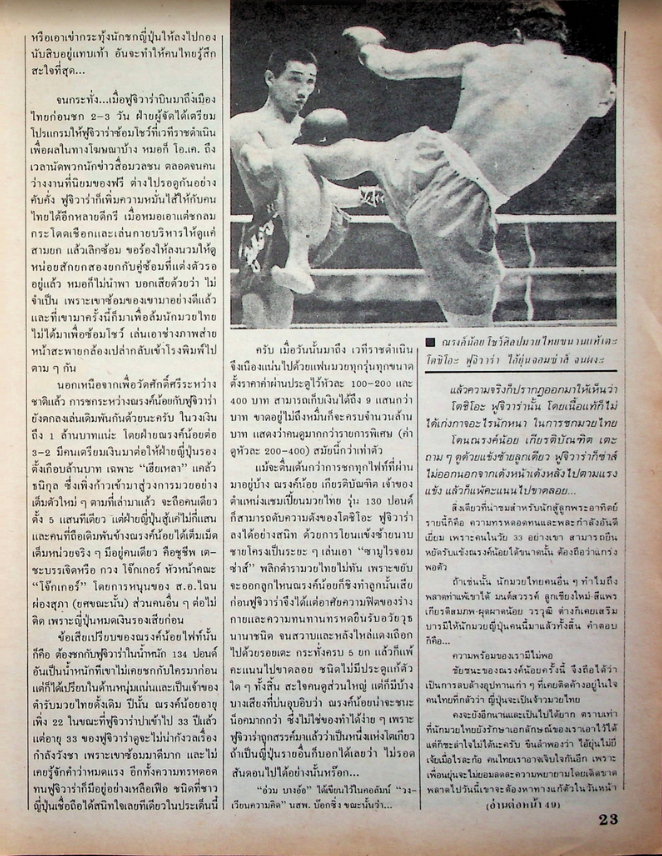

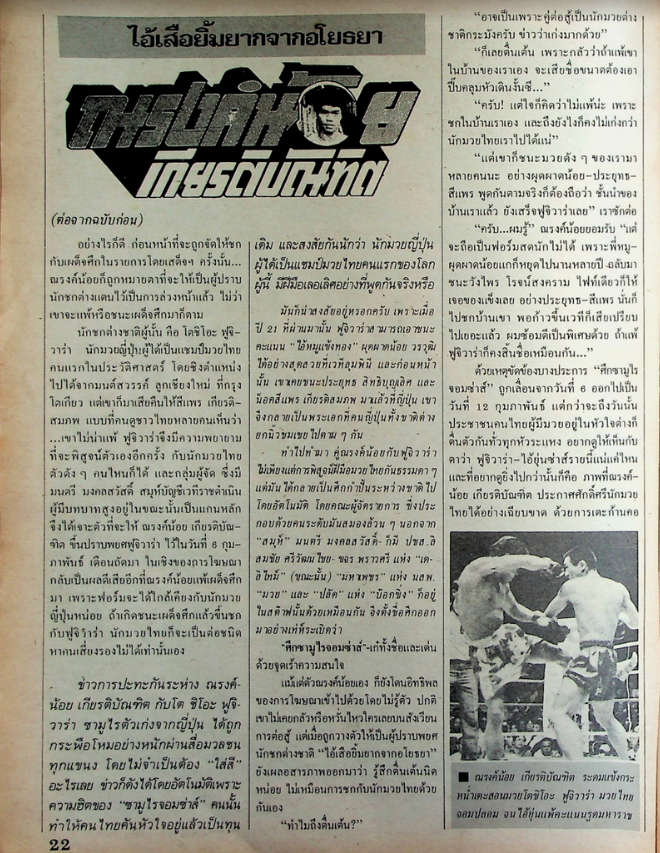

Translation: (Continued from the previous edition (page?) … However, before being matched against Phadejsuk in the Royal Boxing program for His Majesty [Rama IX], The two had faced each other once before [in 1979]. At that time, a foreign boxer had already been booked to face Narongnoi, and the fight would happen regardless of who wins the fight between Narongnoi and Phadejsuk. … That foreign boxer was Toshio Fujiwara, a Japanese boxer who became a Muay Thai champion, the first foreign champion. He took the title from Monsawan Lukchiangmai in Tokyo, then he came to Thailand to defend the title against Sripae Kiatsompop and lost in a way that many Thai viewers saw that he shouldn’t have lost(?). Fujiwara therefore tried to prove himself again with any famous Nak Muay available. Mr. Montree Mongkolsawat, a promoter at Rajadamnern Stadium, decided to have Narongnoi Kiatbandit defeat the reckless Fujiwara on February 6, the following month. It was good then that Narongnoi had lost to Phadejsuk as it made him closer in form to the Japanese boxer. If he had beaten Phadejsuk, it would have been a lopsided matchup. The news of the clash between Narongnoi and Toshio Fujiawara, the great Samurai from Japan had been spread heavily through the media without any embellishments. The fight was naturally popular as the hit/punch(?) of that spirited Samurai made the hearts of Thai people itch(?). Is the first foreign Champion as skilled as they say? It was still up to debate as Fujiwara had defeated “The Golden Leg” Pudpadnoi Worawut by points beautifully at Lumpinee Stadium in 1978, and before that, he had already defeated Prayut Sittibunlert and knocked out Sripae Kaitsompop in Japan, so he became a hero that Japanese people admired, receiving compliments from fans one after another(?). Thus the fight became more than just about skills. It was (advertised as?) a battle between nations by the organizing team, consisting of promoter Montree Mongkolsawat, Somchai Sriwattanachai representing the “Daily Times(?),” Mahapet of “Muay Thai” magazine, and Palad of “Boxing” magazine were also present, and they named the show in a very cool(?) way, “The Battle of the Fierce Samurai.” Even “The Smiling Tiger of Ayothaya” Narongnoi who was never afraid or shaken was affected by the advertising, confessing to the media that he felt a little scared, unlike usual when he faced other Thai boxers like himself. “Why are you scared?” “Maybe because the opponent is a foreigner. There’s news that he is very talented.” “So you’re afraid that if you lose to him in our own home, it will give us a bad name and be very shameful for you.” “Yes! But my heart knows that I can’t lose because I am fighting in my own country. And in any case, he probably won’t/wouldn’t be better than our boxers. “But he has defeated many of our famous boxers such as Pudpadnoi-Prayut-Sripae. To tell the truth, he must be considered a top boxer in our country.” “Yes, I know” Narongnoi admitted, “but Pudpadnoi could not be considered to be in fresh form as he had been declining for many years and could only defeat Wangprai Rotchanasongkram the fight before(?). [Fujiwara] fought Prayut and Sripae in Japan. Once they stepped on stage there, they were already at a huge disadvantage. I trained especially well for this fight, so if I lose to Fujiwara, my name will be gone(?) as well.” “The Battle of the Fierce Samurai” was postponed from February 6 to February 12, but Thai boxing fans were still very excited about this matchup, wanting to see with their own eyes how good the spirited Japanese boxer was, and wanted to see Narongnoi declare the dignity(?) of Thai boxers decisively with a neck kick, or fold the Japanese fighter with a knee. Win in a way that will make Thai people feel satisfied. [Photo description] Narongnoi Kiatbandit used his strength to attack Fujiwara, a fake Muay Thai fighter until Fujiwara lost on points. Fujiwara flew to Bangkok 2-3 days before the fight. The organizers of the show had prepared an open workout for him at Rajadamnern Stadium for advertising purposes. Many press reporters and boxing fans crowded together to see Fujiwara. Their annoyance increased as all he did for three rounds was punch the air [shadowboxing], jump rope, and warm up with physical exercises. After finishing the first three rounds, he was asked to put on gloves and do two rounds of sparring with a person who was already dressed and waiting. However, Fujiwara’s doctor told him that it was unnecessary. This time he had come to defeat a Thai boxer, not to perform for the show. Photographers shook their heads and carried their empty cameras back to their printing houses, one after another. In addition to measuring the prestige of the two nations, the fight between Narongnoi and Fujiwara was also wagered on, with a budget of 1 million baht. Narongnoi was at 3-2 in odds, and someone had prepared money to bet on the Japanese underdog, almost a million baht. Only “Hia Lao” Klaew Thanikul, who had just entered the boxing world, would bet 500,000 baht alone, and the Japanese side would only bet a few hundred thousand. The only person who truly bet on Narongnoi’s side was Chu Chiap Te-Chabanjerd or Kwang Joker, the leader of the “Joker” group, supported by Sgt. Chai Phongsupa. The others could not bet because the Japanese side ran out of money to bet on. Narongnoi’s disadvantage would be that it would be the first time that he will fight at 134 lbs. However, he would have youth and strength on his side, as well as having trained Muay Thai in Thailand(?). Narongnoi was only 22 years old, while Fujiwara was already 33. His 33 years did not seem to be a concern in terms of strength as he had trained very well and never knew the word “exhaustion.” Fujiwara had an abundance of endurance, to the extent that the Japanese could trust him completely on this issue. Yes [krap], when the day came, Rajadamnern Stadium was packed with boxing fans of all ages. The entrance fee was set at 100-200 and 400 baht per person, and the total raised was over 900,000 baht, less than ten thousand baht short of reaching the million baht mark. This means that the number of viewers was more than double that of the special events (200-400 baht per person) nowadays. Even though it was more exciting than any other fight in the past, Narongnoi Kiatbandit, the 130 lbs champion, was able to completely extinguish Toshio Fujiwara by throwing his left leg to the ribs every now and then. This made “the Samurai” unable to turn the odds(?) in time because Narongnoi would always stifle him. Fujiwara could only rely on his physical fitness and endurance to stand and receive various strikes until his back and shoulders were red with kick marks. After 5 rounds, he lost by a landslide, with no chance to fight back at all. Most of the audience was pleased, but there were some who complained that Narongnoi should have won by knockout, which was not easy as Fujiwara had already established that he was the best in Tokyo. If it were any other Japanese boxer, it would be certain that he would not have survived. “Am BangOr” wrote in the “Circle of Thoughts" column(?) of the boxing newspaper at that time: “Then the truth came out to show that Toshio Fujiwara was not really that good at Muay Thai. He was beaten by Narongnoi Kiatbandit who only used his left leg. Fujiwara was frozen, bouncing back and forth with the force of his leg, and he lost by a landslide... The only thing worth admiring about this Sun Warrior is his endurance and excellent durability. For someone at the age of 33 like him to be able to stand and take Narongnoi's kicks like that, he must be considered quite strong. Why, then, did other Thai boxers lose to him? Monsawan-Sriprae-Pudpadnoi-Worawut have all helped strengthen this Japanese boxer. The answer is that their readiness was not enough(?). This victory of Narongnoi is considered to be the erasing of the old beliefs that were stuck in the hearts of Thais who were afraid that Japan would become the master of Thai boxing. It will probably be a long time and it will be difficult as long as Thai boxers can maintain our identity. But we cannot be complacent. If we are arrogant and think that the Japanese will not give up, we Thais may be hurt again because they will not give up. If we make a mistake today, he will have to find a way to make up for it tomorrow."

-

RasheedDickinson joined the community

-

shkokkaindia changed their profile photo

-

shkokkaindia joined the community

-

harrybrock joined the community

-

modelincity joined the community

-

Ishikagupta changed their profile photo

-

Ishikagupta joined the community

-

Thailand Gym and Training Advice for Beginner

Imagineer replied to EJJ's topic in Gym Advice and Experiences

I've been to Watchara gym a few times for PT but haven't tried their group classes. Its more of a "casual" gym (its air conditioned (which is not a bad thing!), clientele are (mainly) non-fighters) but the trainers are knowledgeable/experienced. Honestly i've hopped around in BKK for a bit and i haven't come across objectively bad trainers - its more about finding one that has a personality/teaching style that fits you. The gym is used to foreigners (you book classes through Klook). If you do go for PTs I would recommend Em - he does focus on technique and speaks very good English. You can do privates with them on Sundays (most gyms close on Sundays). If you go gym hopping in BKK and want more training on Sunday, you could try them out for a Sunday PT session. -

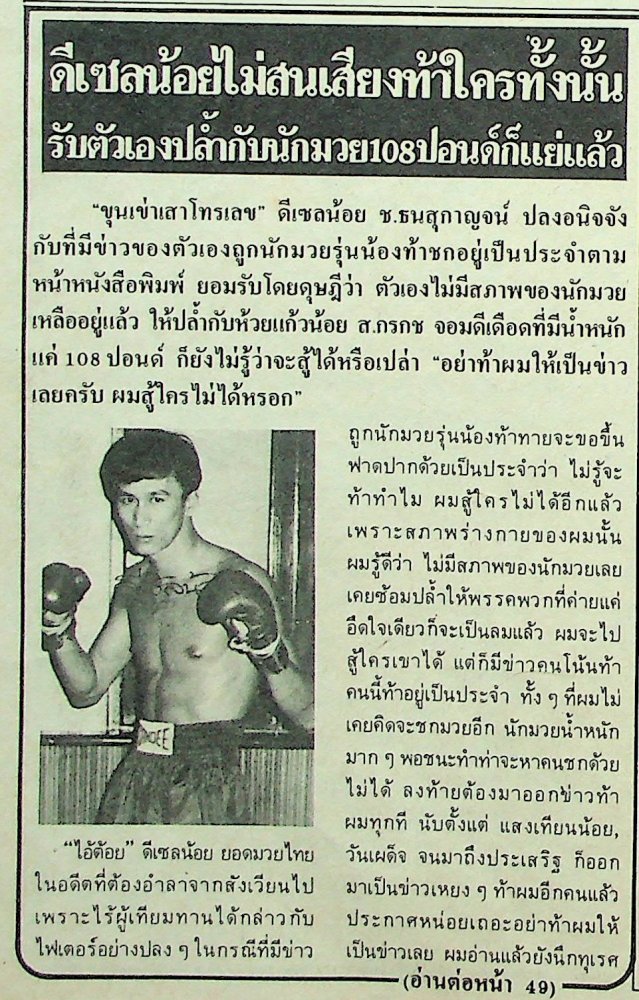

Well, this is really interesting. We sent this little stub article to Dieselnoi and he said the whole thing is just made up (and that writers back then would make up a lot of things). He'd never seen this, and its very, very far from the truth. He mentioned that 2 years after retirement he went to help out Wanpadej in clinch (one of the fighters mentioned in the article) and Wanpadej definitely could not stand up to him at the time. And none of the other fighters mentioned as well. As to the 108 lb Hapalang fighter that he appears to praise here, he had a fight coming up in this magazine, so maybe this was a way of hyping him? In any case, even turning to the articles of the day there might be an entire additional layer of suspicion or interpretation necessary. Magazines themselves creating their own narratives.

-

ricoadammuaythai started following Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu

-

ricoadammuaythai joined the community

-

Facebook Videos Downloader joined the community

-

PKS joined the community

-

Narongnoi also fought Benny Urquidez in March of 1977 (Los Angeles, California), a fight that ended in a riot. You can see that fight here: Just a little more history context, here is a 1977 card from Sylvie's archiving: "In 1977 Dieselnoi, still 15 yrs old, fought Paruhat at 118 lbs. On the same card the Wichannoi fought Narongnoi at 135 lbs. 10 ms later Dieselnoi faced the legend Wichannoi & got his first loss, jumping from 118 to whatever weight. "

-

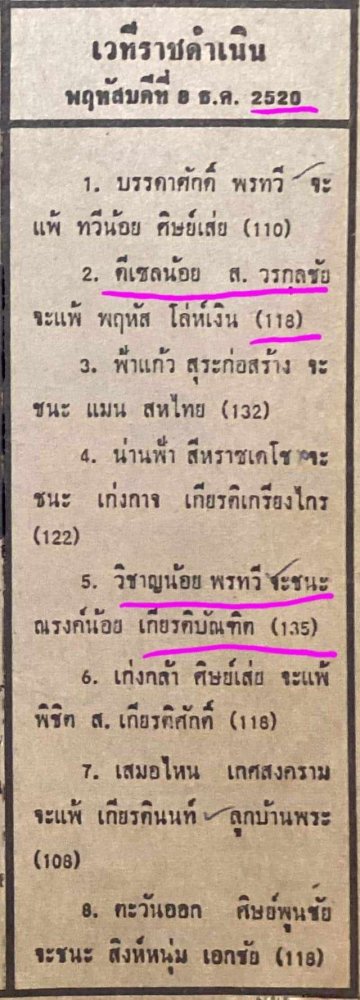

Narongnoi Fujiwara - Fighter Feb 20, 1987.pdf above, the higher res PDF Maybe someone could (machine?) translate the article and post it. Just adding the article here for archive purposes. A long history of Japanese fighters pursuing the glory of Thai ring fighting excellence, this was a milestone fight in Thailand. Fujiwara would end up with a curious career record boasting an enormous number of knockouts mostly fighting in Japan. In March of 1978, not even a year before this fight, he had won the Rajadamnern title, fighting in Japan (a knockout somewhat by tackle). Would be interesting to read this piece to see how Thai media looked back on the Narongnoi fight almost a decade after.

-

Here is the fight vs Wangchannoi in January of 1994 Karuhat felt he won, on which the 1993 FOTY lay...Karuhat desperately wanted a quick rematch to get revenge, but Wangchannoi begged off, and wouldn't face him until after the FOTY was announced. Karuhat instead defended his Lumpinee belt vs Boonlai and then Chatchai.

- 2 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- karuhat

- wangchannoi

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

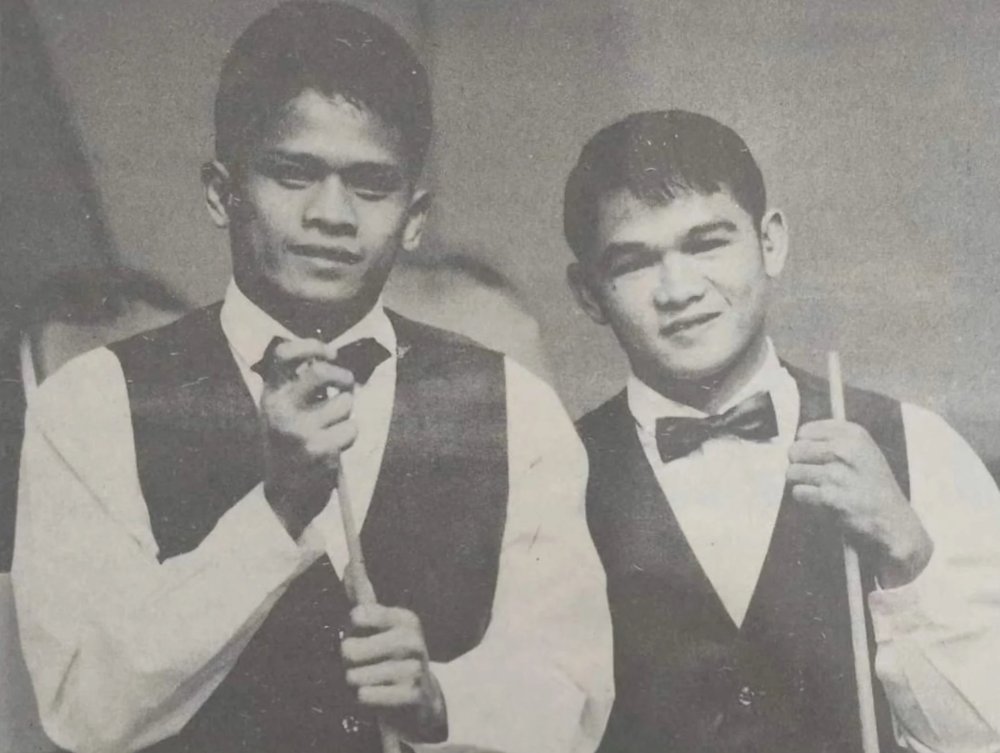

My favorite photo illustrating this is them with their bowties at the pool hall. While Karuhat was fighting for the 1993 FOTY award at 122, defending his belt vs a monster roster of 122ers, an award he would lose to Wangchannoi (due to a razor close fight he felt he won in January of 1994), he was just a smaller sized person.

- 2 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- karuhat

- wangchannoi

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu started following Lumpinee Rankings, December 30 1988, Fighter Magazine

-

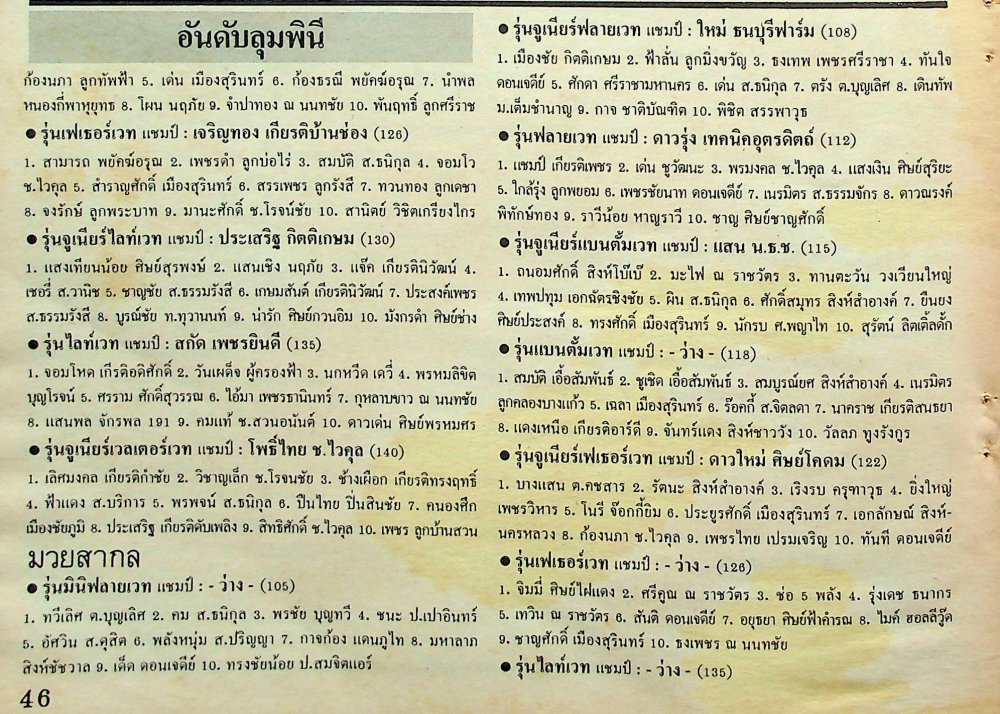

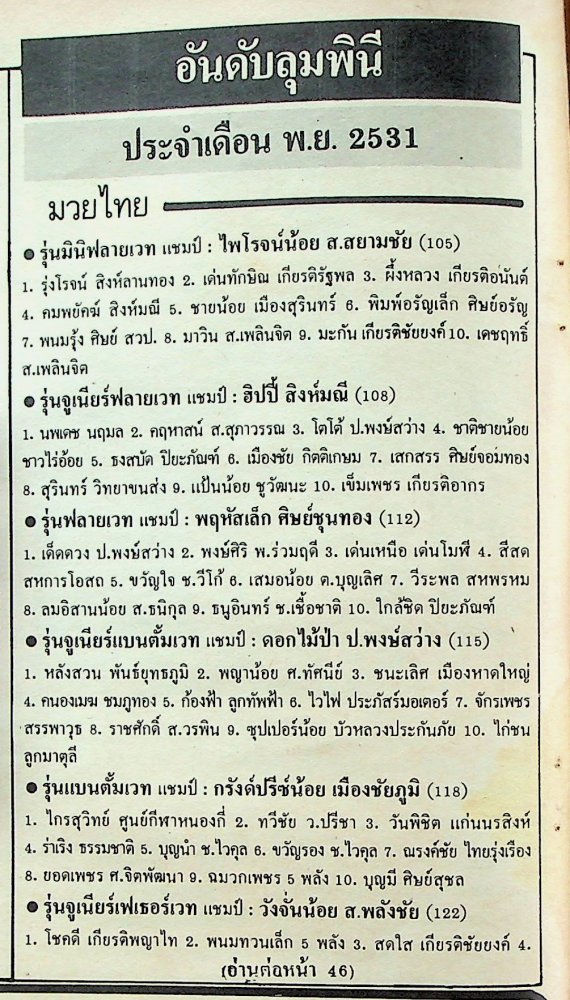

Of note in the end of 1988 rankings, Somrak was ranked at #6 at 105 lb. Hippy was champion at 108 lb, Karuhat was ranked #2 at 108 at the same time that Wangchannoi had just become 122 lb champion. Karuhat does not get enough credit for how much he fought up in size. He didn't still weigh 108 when he became 122 lb champion, but he was properly a 115 lb fighter when he did. Wangchannoi and Karuhat are one year apart in age, they are just differently sized men. Rankings continued: of note, Jaroenthong was champion at 126 lb while Samart was ranked #1 behind him. And Sagat was 135 lb champion, with Gulapkaw (now head trainer at Jitmuangnon) was ranked #7 (he would later become champion).

- 2 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- karuhat

- wangchannoi

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Sylvie is collecting old Muay Siam and Fighter magazines, reading and studying them. She puts up some of what she finds (archiving articles in high quality JPEGs and PDFs) on the Muay Thai Library Instagram, but this sub forum is where we can post those archives much more thoroughly, and where others can also drop in articles and help with translation or commentary.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

This is the March match up of Dieselnoi's teammate Chamuakpet and Langsuan, both Muay Khao legends, where Ngo Hapalang is killed in the corner. Dieselnoi has already hopped into the ring to receive Chamuakpet between rounds. The unspoken presumption is that the killing was at the behest of the powerful Muay Thai promoter Klaew Thanikul, a very power mafia King Pin, who had significant connections to the Hapalang gym and its fighters. Klaew for instance promoted the Holy Grail fight between Samart and Dieselnoi in 1982.

-

Quick summary (maybe others can contribute). With fighters like Sangtiennoi and Wanpadej fighting bigger there seems speculation that Dieselnoi could come back and fight after almost 3 years off. He says he would but that though he trains and is conditioned his skills have declined and even struggles clinching in training vs Hapalang's 108 lb Huaygaewnoi Sor. Karakod. This article comes out just after the owner of his gym Ngu (Ngao) Hapalang was assassinated at the ring in Lumpinee between rounds in the Chamuakpet vs Langsuan fight (a month before their rematch). The gym must have been in terrible turmoil. Also, this is the month before his good friend Samart returns to the ring during his FOTY comeback run, after a 4 month rest, to face Samransak. Yodthong had said that Samart had a hand fracture he was going to not get surgery for at the time. So,speculating (?) one imagines that Dieselnoi & Samart are out partying a bit, Samart (famously a reluctant trainer at the time) not fully on board with the comeback (?), and Dieselnoi being interviewed about coming back. Just some possible context setting, we'd have to ask him. The story about him struggling in clinch vs Huaygaewnoi in training is also interesting, though sounds extreme. Clinch is a very fast-eroding skill, perhaps the fastest eroding of all Muay Thai skills, and Dieselnoi in the very clinch heavy gym wasn't especially renown for his clinch skills by comparison. He told us that Chamuakpet would trip him all the time, and Chamuakpet has said it wasn't a Dieselnoi strength (when compared to him and Panomtuanlek, where were legends of clinch). Dieselnoi was more of a neck-blumb and kill knee fighter, so he really relied on that double collar lock to finish opponents. If it wasn't sharpened he might struggle?

- Earlier

-

Hello all! Just like other users, I am looking at Sit Thailand, Manop, and Hongthong. I’ll be in Thailand for a 4 week training camp. Totally skippable background info: I learned about Muay Thai when I was a Peace Corps Thailand volunteer and now have racked up more than a dozen fights in about 2 years back stateside. I wouldn’t describe myself as highly skilled; just relentless. I plan to move to Thailand indefinitely but for now, I have a couple of opportunities coming up and may be fighting some VERY accomplished women (I fight at 118) and so I’m taking the opportunity to for a camp. Does anybody have suggestions with the following info in mind? •I’m female, fighting 118 •this is a camp for a specific fight •I don’t have an unlimited budget (which is why I’m not going to Kem haha); I’ve just been saving for years •I want to spar and clinch a lot •I like smaller more intimate training and really want to work on my technique •I’m not skilled enough to attribute myself with a certain style, but I would say I lean muay khao in my forwardness and love for clinch. My fight IQ is… coming along lol Hong Thong looks awesome, and I do like that it’s close to the center. I love their enthusiasm and there would be more sparring partners for me, I imagine, as it seems a bit larger, and I love the on site accommodation. I won’t be able to rent a bike. (I do speak Thai though so I’m not at all worried about navigating public transport and asking for help.) Manop sounds like a rad teacher, and he trains probably one of the the best women in the world at my weight, but I don’t even know if I’d get to spar her Sit… I just keep hearing good things! Thanks so much; I welcome any suggestions, and while I’m excited to be in the north (I lived in Korat so that’s why I was thinking Kem initially) I am open to other suggestions.

-

For anyone interested after reading the first part of my post: In the meantime i trained with a boxing Coach who learned his foundation in the Kronk Boxing Gym in the U.S. (partly with trainers at an international Level). From his point of view you can and should rotate the elbow upwards, as long as you dont flare out too early.

-

raradrivingschool changed their profile photo

-

Rate my instructor

The Bongo replied to Doloriferous's topic in Muay Thai Technique, Training and Fighting Questions

Your instructor is a fool. Pad holding is a serious technique in its own right. He should have taught you how to kill the power in a kick with movement. -

TatianaVoronova changed their profile photo

-

Joelxthewolf started following Dry Needling (electro-acupuncture)

-

Signature Prestige changed their profile photo

-

was doing a kick boxing class and the student i was paired up with had a strong roundhouse kick, i was holding thai pads for him. i told the student to kick lighter and he did as it was hurting my arms, but instructor came along and edged him to kick harder even when student said yea he cant handle the kick . i could take it for 6 kicks but after that my arms started to really hurt. i evaded one kick as it was too hard and instructor said you need toughen up. i think instructor was trying in injure me. my arm is bruised also got feeling instructor doesnt like me as he didnt come along and give me pointers in my technique but he did with other studentss whats your thoughts.

-

That was such a good read, Thats exactly what I'm looking for.

-

tmagicmushroomss changed their profile photo

-

kunjanaswetha changed their profile photo

-

Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu started following Calf Pain

-

Calf Pain

Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu replied to Brentwood's topic in Muay Thai Technique, Training and Fighting Questions

Do you stretch, use a foam roller, or get massages? -

Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu started following Thailand Gym and Training Advice for Beginner

-

Thailand Gym and Training Advice for Beginner

Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu replied to EJJ's topic in Gym Advice and Experiences

Sounds like you have a good approach, and a great trip. I think gym hopping is okay, but if you find a place you like it doesn't mean you have to leave. Maybe move around with the idea that if you find something good you can just stay and enjoy it. Kem or Sitjaopho for 6 weeks is a very different experience. Maybe the thing to do is once you get up to Chiang Mai see how you feel about moving around, and if it doesn't vibe with you and you haven't found a place you love consider changing it up and going to Kem's or Sitjaopho. The key to Thailand is being very flexible, discovering things that connect with you. It won't be like how you expect. -

Hi all, thank you for making this resource available there is so much useful information available here. In September I have the opportunity to visit Thailand for 6 weeks to train. I have no experience with MT although I am a generally active male in my mid 20s. Would very much appreciate advice on training before the trip and gyms to visit during the trip. Firstly, training and conditioning beforehand. Work and other commitments make attending MT classes frequently problematic day to day. However, I run 3x per week for 30-40mins (occasionally longer) and strength train 2-3x per week. I have a background in endurance running and cycling. The plan for the next few months is to carry on this routine, perhaps with the inclusion of 5-10 minutes skipping before runs. Is there anything else I should focus on in order to arrive in Thailand ready to train? Secondly, on trip logistics and gym selection. The plan is to fly into Bangkok and take a combination of classes and privates, probably training only once per day while acclimatising to the heat, humidity and training. Have read good things about Petchindee, Sangmorakot and Watchara gyms. After 4-5 days in Bangkok, the plan is to head north to Chiang Mai to try a few gyms and eventually settle down for 2-3 weeks of training 2x/day. The main appeal of Chiang Mai is the density of gyms and affordability. Gyms on my list include Dang, Bear Fight Club, Manasak, Manop, Sereephap, Sit Thailand and Lanna. The objective of the trip is to pick up a solid foundation in MT, with an emphasis on sound technique and fundamentals (including the clinch). Absorbing local culture is also important of course. I view fitness gains as a byproduct of training rather than an end in itself. My questions are: -Are there any obvious gym options I am missing? Particularly for a beginner seeking technical instruction in the basics. -Is it a waste of valuable time to gym hop too much? Would it be more beneficial for my development to settle down sooner or head straight to a well regarded camp like Kem or Sitjaopho for 6 weeks. Any advice and thoughts on the above would be much appreciated. It will certainly be a great and instructive experience either way.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

.thumb.jpg.cd79266be0eb8c9d36059aaf2c7ea5c7.jpg)