-

Posts

2,274 -

Joined

-

Days Won

502

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

For even more context on this, Sia Boat is kind of the big next generation promoter and gym owner of today's Muay Thai. He's been very active trying to foster a new unity image of the sport, and this move to embrace Fahwanmai, who maybe typified what many, broadly in the country may feel is wrong with Muay Thai, the nakleng, the gambler. By taking Fahwanmai under his wing he was symbolically offering refuge to a class of people who had been under great scrutiny ever since the Muay Thai community took the huge hit of a blame for the initial COVID cluster (which centered on Lumpinee stadium). Lumpinee shut down, the military also permanently closed two important uncountry stadia under the auspices of ridding its of gambling influence, and the new Lumpinee promotions are taking very stark - but perhaps unsuccessful? - stances against gambling, at this point even barring cell phones on the grounds. It's enough to say that Sia Boat's bold, symbolic move to "save" Fahwanmai took a terrible turn with this thrown fight. Yes, pretty much everyone agrees that gamblers have too much influence on fights, able to move the odds during the fight, and nearly force particular wins and loses, but, the act of gambling on fights is deeply woven into the culture and passion of Muay Thai. Sia Boat was seeking a way to embrace a possible future that includes the cohesive powers of gambling, while minimizing its very public abuse.

-

I really don't know how France tends to score Muay Thai fights, so I'm only guessing. But...France does seem to have probably the closest, longest heritage to traditional Muay Thai, so maybe they take pride in being more traditional? The one clue we might have is that the ref in the ring ran the fight VERY much like Golden Age fighting. More traditional than current day Bangkok stadium reffing. I really don't know though. We had a fight where the ref in the ring, and both fighters fought in a very traditional way, which was pretty surprising. I have no idea about the judges at ringside. I would say though, an org like the WMC can't really impose how judging is to be done. They can say how it is to be done, but people read with their eyes. I'm not really saying the scoring was right or wrong, given it was in the West. If you read my original post I tried to cover that. No, just like with a kick, the "open side" (the side and direction the belly button is pointing) is the higher scoring point. If you are in orthodox, if you take strikes coming from your right, they score higher. This is for strikes that are unblocked by the shins.

-

In traditional scoring narrative is one of the most important criteria. Yodwicha was ascending moving from 2, 3 and 4, and each round matters more than the last, with the exception of the 5th round. It's not points added up on a calculator. Also in clinch it matters more which side you land knees on (open side or closed side), and if you land with the point of the knee rather than with a slap of the knee. And yes, body language and what Thais call "ruup", which is your posture vs your opponent's posture, also matters. Traditionally, you can't just add strikes up. But, Vienot seemed to perfectly understand - AND fight - this fight from a traditionally score perspective. The 5th round was fought more or less exactly how it would be fought in Thailand. A 5th round in the West you'd find both fighters pressing hard trying to outscore the other, adding up strikes. In Thailand the fighter who has the proverbial lead retreats and defends his lead. The trailing fighter then advances, which is largely a public acknowledgement that he is behind on the score card. It is up to the advancing fighter to do something dramatic, or at least take a dominant score to reclaim the lead (depending on how big of a lead there is). This is exactly how both Yodwicha and Vienot fought, which placed the entire fight in the context of traditional scoring (which to me was kind of surprising, and admirable). This would mean that narrative really matters. And, given how the 5th round was fought, basically with Vienot conceding, you'd expect Yodwicha's camp to be shocked. This was, especially with how the last round was fought, what in Thailand Sylvie and I call "a close blowout". Once the fight plays out where it is clear and acknowledged by both parties WHO has the lead, and then nothing happens to change that, that's a blowout...because there is no question, but, the fight might also be closely fought throughout. It's like a largely close footrace, and then both runners both let up at the tape. It might have been close much of the race, but the let up shows that both runners know who has the lead, the one breaking the tape.

-

A follow up, Yodwicha's team says they have turned down an offer for $115,000 to fight again for the same title in a rematch: Yodwicha, put off by the way the Vienot WMC title fight in France was handled just turned down 100,000 Euro ($116,000 US) for a rematch for the belt, a fight that would be in Las Vegas. "We have a long cue" his wife writes.

-

There was an update on this announcement which revised the new start date, pushing it closer to October 16, along with complaints that somehow the last stream was hacked (?) by nefarious gambling forces, and even the statement that they would look into the possible corruption/error of a decision of a 3 round fight on their last card, between a Venum fighter and an FA Group fighter, which is quite striking given the low profile of such a fight. Seems pretty Topsy-tervy right now, continually in adjustment as things unfold.

-

I should add, there is also a very odd thing that happens in the hybrid gyms that have a reputation of being "authentic". Where the training of Thais and of Westerners can be quite mixed. They train might regularly against or with each other, etc. But these almost always are TWO different gyms, existing in the same physical space. There is the Thai gym, with its business model and its customs and codes of control and expectation, and there is a Farang gym, that has it's buisness model and customs of practice. As a Westerner you simply can't see that there are actually TWO gyms. You think you are in the same gym, having the same experiences, more or less. But they are different. What's interesting about this article and interview is that the Western gym is starting to bleed into the Thai gym, more and more, in unexpected ways.

-

This is the thing, right? The problem is - or one would imagine it would be - that westerners are pretty ill-equipped to even understand these kinds of things in the first place. Almost the entire train/fight set up is framed as a commercial enterprise, conditioned under the "customer is always right" value system, and when it evolves into a Sponsorship this is often just seen as more of a commercial bargain for the westerner. They no longer have to pay for training (and the implied compliment that they are so GOOD they are being treated like a Thai)....when in fact you can't possibly be treated "like a Thai" in the real sense, because you don't really see all the bounds of the Thai subculture. To be sure westerners can and do have romanticized notions of respect and hierarchy. You can wai with sincere appreciation everytime you see the gym owner in the gym. You can listen to your padmen, and apply remarkable "work ethic" (in the Western value) which is cross-read quite well in the Thai world, but...you very likely would have no sense of things like: If you are in the 6th grade and your teacher says something that is blatantly wrong in passing, like "Germany won WW2" you would never raise your hand and correct them. Or, more close to home, if your gym owner or lead padman lost interest in you, or stopped finding you fights, this would 100% be on you, and in no way their fault or failing. You would have no idea that this is part of the traditional world you are trying to step in. There are other things that are complicating. We might think as fighters under a gym name that all you need to do is work hard, fight well, be respectful. That for sure is a good start. But if you fight well and win, and win...and win (bringing shine to the gym), you actually can be creating all kinds of tensions you can't see. The call of attention to your gym actually stimulates gossip and whispering in the community. We hear none of this, but this is a huge world of importance in the Thai Muay Thai online & local community. Anyone who shines invites detractors and lots of counter-whispers. The Thai subculture is extremely gossipy, in a way that really impacts the subjects of gossip. So, even if you do everything right, by the book, you can actually be intensifying the world of those you respect and obey, which means issues of freedom or performance in the future can get really complicated in the hierarchy. To take even a small, but pretty common example. Just asking a trainer other than your lead padman for advice, or worse, requesting to do pads with them, can be a HUGE political shift in the gym, if you are a fighter who has gained some value. For a western fighter this might just be "I just want to get better" or "see something new". I guess I'm saying, I agree, you need to accept some things if you want the "traditional" experience, but very few people are even equipped to imagine what those things might be, just because we bring with us our own value system, and our own sense of what is fair and respectful. The "REAL" traditional experience, perhaps much less common in Thailand today, is probably what the legend Pudpadnoi told us when we asked him why he left Muay Thai, pretty much at the peak of his career. "Because I couldn't do anything at all, no freedom at all, no control, when you eat, when you sleep, when you do anything." Sylvie said: "It's like a solider." and he said, "It was much worse." Leaving Muay Thai was like leaving the military. Maybe kaimuay are not like they were in the elite camps 1970s...and even if there are some that are close Westerners wouldn't have contact with them, but running through all traditional style camps is this very hard vein of control that we just don't see, or see very rarely.

-

watch the full fight here - note, the use of elbow pads is due to French law This is not so much a commentary on the controversy in the scoring - which I believe has led to the WMC vacating the decision and the belt, a decision they will re-award on review, leaving the belt to fought for at another time - but the fight itself which was really remarkable in many ways. At a time when clinch is being squeezed out of "modern" "Entertainment Muay Thai" promotions like ONE, Superchamp and MAX, this fight was refereed in such a beautiful Old School way it really went beyond what you'd find in Bangkok Stadia Muay Thai. The way that the clinch was allowed to go, and work itself free even from "stalled" positions was just pretty much 1990s Golden Age Muay Thai. And there is a lot to be commended in Jimmy Vienot to even keep up and fight through that kind of ruleset and aesthetic. He did have visible size on Yodwicha who I believe was fighting above his usual weight, but he was game for this kind of fight, through and through. The other thing that was pretty interesting to me was just how ineffective Yodwicha was in the clinch in the first two rounds. In his stadia days Yodwicha was the most dominant clinch fighter in Thailand, but he has spent a long time out of traditional Muay Thai scoring, having converted to a potent hands heavy attack that has kept him on top of the International fight scene. It is not often you see a Muay Khao locking fighter convert so seamlessly to the more Kickboxing-like promotions where he can face western fighters, One thing I had noticed on many of Yodwicha's fights in the International Style was that he actually no longer seemed dominant in the clinch. Even in short engagements he would appear uninterested in imposing himself there, even quickly, if the rulesets allowed. He had left behind his fame as a clinch fighter, it appeared, and fully embraced an identity as a Striker. Clinch dominance is actually a skillset that is, I believe, one of the most fragile in the sport of Muay Thai. It is so much reliant on feel, if you don't continually train AND refine your tool box you will lose a lot of your effectiveness. It's full of nuances, leverages and timing that just erode, in my opinion over the years, and you just have to work to maintain or regrow that elite sense of control. When watching Yodwicha in the first two rounds I was pretty surprised just how ineffective he had become in his lock game. He was taking outside arm positions and getting sealed. Jimmy had put a ton of work in, my guess was that Yodwicha, having transition to striking, put most of his work elsewhere, and it was showing. Jimmy has size, but it shouldn't be something one couldn't overcome. Then the 3rd round came. And this is what made this fight spectacular. Yodwicha switched up. He shed his Striker Identity and reverted back to his "Dern" Muay Khao fighter of his Bangkok Stadium days, when he won Fighter of the Year as a 16 year old. And see how his entire clinch game changed once he became a dern fighter. He no longer was taking bad lock positions from the outside. He started transitioning IN the clinch itself. He fought for that inside position for the right arm, he slumped out of waist clinches, he stance switched out of overturns. Watching this is just such a beautiful thing, and a big key to the higher vocabularies of what endless clinch fighting looks like, and is. There is a great deal of vocabulary in Yodwicha's scoring rounds, it was inspiring as a lover of clinch as an Muay Khao art to see. It needs to be stated, two things made this performance - this time capsule reversion to his Muay Khao days - possible. The first was that Jimmy Vienot was totally up for it. He contested all the transitions, he fought for and retook positions, he forced Yodwicha to keep finding a new advantage, AND the even more important thing is that the ref just let it all go. He let it evolve, evolve and evolve. What was a Golden Age flashback fight would turned into a completely stagnant clinch-break fest if the ref had applied modern sensibilities about the clinch. The theory that clinch is boring largely has been propagated through the repeated boring breaking of clinch. This beautifully contested fight could easily have been turned into a snooze fest. Also quite beautiful is that the fight itself was fought under a traditional, narrative scoring aesthetic. Again, Old School. I have no idea how it was scored in judging minds, but both fighters fought it like a traditional fight. This meant that round 3 and 4 were highly weighted AND round five was fought in the traditional Thai "I have a lead, I will defend, you will chase" ethic. Personally, I thought that the choice of Yodwicha to fight the 5th round in this way on an International stage was really, really risky. The West doesn't understand the 5th round all that often, there were boos from the crowd, but as Jimmy Vienot actually showed that he understood the 5th round aesthetic himself, and fought the round that way just as if he were in Thailand, it makes perfect sense that it should be scored in the Thai way...which would give the fight to Yodwicha...you would think. Thank you for the WMC and the French aesthetic commitment to traditional Muay Thai so that we could even have a fight like this. Other Thoughts On The Fight I also though that by Yodwicha fighting the first two rounds as less important and waiting to dern in the 3rd round, in an Internationally staged fight. It makes perfect sense in a traditionally scored fight, you transition to your most devastating game in the scoring rounds, but (I'm pretty sure) the WMC has 10 point must system, and it would really be unclear if non-Thai judges would apply such a scoring system with Thai sensibilities. You risk putting yourself in a meaningful deficit on the scorecard. I generally believe that you have to take circumstances into account, and change your fighting approach to any kind of anticipated built in bias, whether that is something in the ruleset, the judges, the place a fight is fought. You can't just go according to what is "right", you have to fight to overcome expected bias. Just fighting in France would give an expected bias, even if its an unconscious bias of very otherwise fair people. Also, of course, the beautiful slipper, transitioning locks of Yodwicha's mid-fight game was not really close to what he was when he was stomping the grounds of Lumpinee. He is still a long way from that kind of training and expression. It was just beautiful to see it come out again. Something to watch in those rounds is the way that he was manipulate his body, or his stance, to continue with his attack, another is to look at the quality of the knee strikes themselves. People who clinch train a lot sometimes lose the very form of a scoring strike. The slap with the knee, as one does in training, or even pantomime knees. Yodwicha had this extra dimension to his knees which made them scoring knees, speaking broadly. Just as with punches, knees need to be scored in how they connect, not just that they are thrown. Sometimes in Thailand you'll get credit for just the gesture of knees, showing balance or demonstrating control over your opponent, but when some knees are connecting, especially on the open side of the opponent, these have a much, much higher value. It's not exactly clear at this point how the WMC will handle this decision, all we have is something Yodwicha's wife has reported. Thais, as expected are pretty upset about the fight, and maybe it is because of just how traditional and Old School this fight was fought. It was so "Thai", that Thai scoring is even more expected I would imagine. Yodwicha says in the video clip of his protest "why would I come forward in round 5 if I'd already won 3 and 4?"

-

On the post, very little comment other than "you just have to accept this", a kind of resignation of the way it is. Well, he feels disrespected by another or other gyms, to be sure. But in this relay of his thoughts he is appealing to an authority to step in and regulate these kinds of things, because the problem seems to be growing. I think so. The problem is being seen as between different gyms, but also between fighters and their gyms. Loyalty is a complex thing here in these cases. As you know, Thai culture is much more hierarchical, concepts of family and inclusion are hierarchical, and this butts up against models of commerce, the freedom of a market, and also in many cases fairness. Also, the traditional "loyalty" conditions have been read as exploitative by the West when it comes to Thai practices some times. Basically once that contract is signed, often at a young age, your entire career is governed by your relationship to your gym owner. There are so many competing values of what is fair, proper, respectful here. That is very interesting. That sounds like a case where the community of local gyms contain between themselves rules of engagement. These are often hidden customary agreements, or ways of flexing power in the community that Westerners might not at all see or notice. The appeal to a regulating authority in the above case is likely because he feels he cannot control the situation just through social, or local flex. In either case the value of a western fighter seems to be rising in the subculture. And as it does westerners may find themselves bumping into the otherwise invisible powers of control that reside in the culture. It's a very complicated thing - especially at this time of COVID - gym owners sometimes stop investing in the training or growth of a fighter who has been with them for a long while. This of course can happen with Thai fighters as well...but they are contracted and locked in.

-

Thai language source This first time I've seen this issue publicly stated, Sylvie's paraphrase of the Thai news: "Sia Riam" the head of FA Group gym in Bangkok is quoted as being heartbroken by the pattern of international fighters coming to a gym and being welcomed with training, sleeping, eating as a group. They come with "no name" but after gaining some recognition or "fame" other gyms become interested and these fighters are swayed by promises elsewhere. He says he is sure other gyms have experienced this and asks for the Boxing Council to make a decision regarding the problem. (The issue being that Thai fighters are bound by contracts and a fighter changing gyms is a contracted sale, whereas non-Thai fighters have no legal contracts. His call maybe that gyms exercise more respect for another gym.) Opinion and Context This issue of farang gym loyalty in Thailand has been a long running one, wherein westerners seek to find traditional training experiences (and even traditional fight opportunities), but in the quest for authentic Thainess also find themselves outside of the structures of control which hold those traditional forms together. Thais largely are both legally contracted to the gym they train under, but also are often somewhat morally bound to the fatherly figures (or even motherly figures) in those gyms, which traditionally can be adoptive families. You'll recall, there was a very large Thai side dust up over this as Buakaw sought to extricate himself from his Por Pramuk contract which had been passed down from the gym's patriarch who died, to the owner's son. Buakaw was a world famous celebrity of fighting and did not feel still bound by his older, traditional contractual obligation, entered into when he was 9 years old. In the West this battle some years ago was largely portrayed as him breaking out of onerous workcamp ownership of Muay Thai, but in Thailand even though the contract he was under felt quite inequitable, some felt this public move was improper. He won his market freedom of movement. This was a rare, very public dispute. Unlike Thai fighters, Westerners on the other hand often found themselves in a hybrid, nebulous place. More traditional gyms that also were westerner-friendly like famous Sitmonchai or Sangtiennoi's gym gave a strong Thai family gym feel and experience, but westerners were not contractually bound to them. This contractless state is common throughout the country. Technically western fighters exist in a kind of psuedo-commercial arrangement, paying for training (and sometimes room and board), but also experiencing the closeness of family-style bonds that make Thailand's Muay Thai like no other Muay Thai in the world. This can become even more complicated if gyms extend "sponsorship" to a western fighter, providing room and board for exchange of fight percentage fees, and also an (unspoken) tightening of the sense of obligation, something a westerner may not fully feel because it isn't their culture. The western fighter may still remain mentally in the western idea of training wherein a "service" is being provided to them, which they pay for (either in monthly fees, or in terms of sponsorship with fight winnings), and in which they as the customer have ultimate choice and authority. For the Thai, they will see it shaded towards more traditional values and obligations. There is no ultimate "right" or even truth here, because each of these value systems are competing against each other, and are layered on each other somewhat simultaneously. But there is capacity for LOTS of miscommunication. One could romanticly attach oneself to the "traditional" model, but perhaps would also have to ignore the degree to which boys are contracted out at a very young age, often, becoming orphans in Muay Thai. There is harshness in the tradition. Or, one can see in the commercial arrangement where the customer is always right a highly impersonal, detached quid pro quo, the kind of which many come to Thailand to escape or be relieved from. Instead, in the past, westerners have found themselves often floating between the two, improvising respectful compromise and struggling through shared expectation. What seems to have changed at this point is I suspect the rise of Entertainment Muay Thai. Entertainment Muay Thai is a promotional style of Muay Thai that has become quite popular with tv audiences, and has given a shot in the arm to western-friendly gyms in Thailand. These televised fights had new rulesets that helped favor western fighters to win (forward aggression, shorter non-narrative rounds, reduced clinch, fought in a lower talent pool) and they drew a younger, more casual audience among Thais. Western friendly gyms suddenly had weekly televised promotions in which to showcase their fighters which not only grew the gym name, but also excited the fighters themselves. In the past a western fighter in a Thai gym largely would not be part of the serious business model of making stadium champions or sidebet stars. Instead they might compose a kind of side project, folding westerners into their Thai training. It varied between gyms just how integrated westerners would become, and some gyms would focus on them more than others, even promoting them, arranging belt fights with international organizations, etc., altering their business model to include more and more Muay Thai tourism. But, Entertainment Muay Thai seems to have done something interesting. It has raised the value of the western fighter, within the subculture itself. Gym names can become associated with Entertainment Muay Thai "stars" (promotions like ONE, Superchamp, Muay Hardcore, MAX), and with this rise in value is the absence of the traditional forms of control. The social bonds of fatherly or family control, or the legal bonds of contracts do not exist. What is really interesting about this FA Group statement is that both the shared family space of the gym, and the legal recourse of rules are referenced. It does not seem likely that this is in anyway to change right now, but as western fighters indeed do grow in value in the fight culture the lack of authority can produce conflicts and misunderstandings. It's also important to see that this issue is not just between a prospective fighter and their gym. It also, as its expressed, an issue between gyms themselves, the sense that other gyms can come in and poach the value in a western fighter that the prior gym has worked to build up. This is probably the even more serious issue. In the West we are much more used to thinking of things in terms of individual decisions and freedoms, and sometimes as difficulties between a person and an authority. But in Thailand its much more socially bound. Difficulties reflect power across the community in something of a triangle. This is because face is an important part of Thai culture. It's not just that a gym might lose a fighter of value (negative profit), its also the social consequences, the loss of status, that can happen when something appears to be taken from you. This is one aspect of how the contracting of fighters works. Contracts aren't just used to control the movements and opportunities of Thai fighters (they are of course, but they are more), they are also used to save face when fighters are leveraged to be moved, often beyond the control of the gym. The original gym gains compensation as a modicum of face. This is a pretty regular practice among smaller traditional Thai gyms that will find that their young star that they have built up locally, since a boy, is now being leveraged beyond their control by a powerful Bangkok gym. They have the contract, but perhaps the family of the boy sees much greater opportunity with the famous gym. The contract then gets sold, and a sign of face is given, even though the gym might not have an ultimate social say in the matter. This leveraging of built (youth) talent is what is being referenced here, but in the context of the built (adult) value of western fighters. If you want the latest in Muay Thai happenings sign up for our Muay Thai Bones Newsletter

-

see the Thai source here Sylvie paraphrases this announcement in Thai: Mr. Chai of GoSport announced that they will cancel all their Studio Saturday promotions (being produced in the Parking Structure next to Lumpinee Stadium), starting October 9th, 16th, and 23rd in order to spend that time rehearsing the "lights and sound" in the real Limpinee arena, ironing out some "timing issues" for a grand show on October 30th. He asks all fighters who had been scheduled to please keep training and be prepared for programs following from October 30th. No word whether the Giatpetch promotion, which precedes GoSport on Saturdays, will also be canceled or not. This is part of the evolving landscape of the New Lumpinee approach to Lumpinee Stadium, which involves intense commitment to producing promotions that have zero gambling influence, modernizing and Internationalizing its image, in this case the GoSport hybrid model of mixed cards with "Entertainment Muay Thai" type fights (3 round fights featuring farang vs Thai matchups) and also 5 round fights with a more traditional feel, coupled with the idea of an app that could give access to fights. GoSport which has been heading this movement had built a small green screen TV studio in the parking structure next to Lumpinee Stadium to be able to produce fights with the Lumpinee name under the Bangkok COVID prohibition of indoor events. Under this improvised solution they were able to put on the described "First Female Fight AT Lumpinee", making history. As the new promotion has been seeking its footing, overcoming a few early difficulties, this announcement anticipates that Thailand (and Bangkok) will be loosening up its restrictions at the end of the month. By shutting down their Saturday Studio shows which had featured their hybrid "modern" approach, they feel they can put on a more spectacular, tightly produced Grand Opening on October 30th, which will likely feature the first female fight IN the Lumpinee ring, the ring which historically had specific ritualistic prohibitions against anyone of the female gender entering its ropes, making history again. If you want the latest in Muay Thai happenings sign up for our Muay Thai Bones Newsletter

-

I hear you, but also understand that probably the most intense, most satisfying reading experience I ever had was as a child having found my mother's Critique of Pure Reason in the garage among so many dusty books - I was maybe 10 years old? - and trying to decipher that text painfully, without any context, as a 10 year old brain, sentence by sentence, almost word by word. I have no idea how far I got into it, but I was at it for months. I suspect I didn't learn very much about Kant's critique but it bestowed on me in the most powerful way a love for the hieroglyphics of Philosophy's over-specialized language, and led to to reading unending volumes throughout my young adulthood years up into my 30s and even 40s. That absolute incoherence, and my belief that special meaning was there, in those words gave me something that empowered my mind more than any cribnotes on Kant ever could. To this day it's a very special memory.

-

I was having a great conversation with Sylvie about the nature of Thailand's Muay Thai this morning, and why when you have the lead in the fight, traditionally, you begin to retreat and defend that lead, instead of marching forward and adding more pressure. You ostensibly "perform your lead" by taking defensive tactics, which to many parts of the world looks like the opposite of "fighting". In a comment on Reddit I was trying to explain this phenomena through how someone like Usain Bolt will ease up and coast into the last 15 meters, in a kind of dominance while everyone else is burning hard, because of a kind of excess, "I don't even have to punch it to beat you". This is a big part of the Muay Thai aesethetic. You can read that comment here: https://www.reddit.com/r/MuayThai/comments/pxtv2x/i_think_people_do_not_understand_how_thailands/hesx7fs/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3 The reason for this is that Thailand's Muay Thai is about dominance, not aggression. Aggression can be a tool toward dominance, but it's only one tool in the tool box. A lot of this stems from the fact that Thailand's Muay Thai evolved to express a Buddhistic culture (and a reason why I'd argue that turning MT promotions into hyper-aggressive shows can contain a hidden cultural betrayal), but as you can see from the Usain Bolt analogy, in the West we can understand this kind of "ease into the tape" signature of superiority. Even in Western boxing we can admire the artful boxer who just toys with his opponent's aggression with an artful jab, evasiveness or movement (think Ali or Mayweather), its not all that far from parts of our own sports values. It's enough to say this led to a really interesting analogy Sylvie gave me regarding the much derided 5th round dance off in Thailand's Muay Thai. Let's say right off there are admittedly big problems with the 5th round dance off. It's safe to say that it is an aspect of Muay Thai that has become distorted and exaggerated, and not only produces unexciting ends to fights, its become the signature of big name gambling's powerful influence in the sport. This post is really about the underlying logic of the dance off, and besides its current flaws, what positive values it is expressing, helping explain how it is also viewed. Why do two fighters dance off the 5th round at times? Why does a fighter who is behind not keep trying, keep fighting?! When one fighter is signaling an insurmountable lead, why isn't the other fighter "heroically" relentless in pursuit? Chess Gives A Clue Sylvie's analogy comes from Chess. In Thailand's Muay Thai there is a definite "Gentleman's Sport" ethic that works to compliment it's absolute violence, so Chess is an interesting parallel. She said to me: In chess once you've gotten to the place in the game where you know by sheer logic you are going to lose you tip your own King over and resign. Masters will resign in positions that casual viewers might not even understand. There are a lot of pieces on the board! What a player is doing when they resign is showing their IQ for the game. If you continue fighting to win from unwinnable positions you can be signaling your inability to even see the board. Yes, your opponent may make an unexpected blunder. Yes, there might be buried in the position of some improbable ability to leverage a draw, but largely what is happening is that you are placing yourself ABOVE this particular game. If you struggled forward, not really realizing your fate, your would be signaling to your audience and your opponent you lack understanding. You can't see. This keys into deeper Thai cultural views that regard sheer aggression as low IQ and somewhat animalistic (non-human). You don't understand Chess. Now, there are all kinds of Chess players, and some of them may become famous for fighting out of bad positions and stealing draws. This isn't to describe what one should do, it's to explain the logic of why a losing fighter would choose to dance off. They acknowledge the board position, they are above this particular match/game. Thai fighters fight a LOT of fights. The tournament of a career is composed of many games. Now, once you get the logic you can also see where the problems are. If there are TOO many sprinters coasting into the tape. If there are TOO many fighters touching gloves in the 5th round, the "board" of the game is being influenced by something (or the match making is very poor). In these cases its explained that the chess board of the fight, the position that fighters are responding to, involves the heavy thumb of powerful gamblers. You touch gloves not only because of the "position" of how the fight was fought, but also understanding the powers that shape the fight as well. You can see that the lead in front of you is of a type that you would look stupid if you fought against it. You would look like you didn't understand the game and how it is won. How the 5th round is fought has changed over the decades, to be sure. It has stretched too far into a direction, but the logic of the danced round remains the same, that of the Chess match. Taking Ideology Into Context Too I also think that there are cultural elements that make this hard to read from a Western perspective. In the West we have a big celebration of the Little Guy. In the mythology of the West we have the story of the insignificant man who through "hard work" overcomes all odds against him. There is not only great romance over this ideological story, fighting itself has been an entertainment form that expresses this romance. We see this in the entire Rocky Balboa Working Man franchise. For us a lot of fighting is about this. I do think these stories resonate with Thai storytelling. Great fighters of the past who became champions out of rural provinces, fighters like Samson Isaan (who literally took the name of Isaan), do represent a kind of working class, provincial victory against all odds, but this is in the context of a much less socially mobile society, than say America. The much older cultural stories of Thailand are ones of hierarchy, and layered, group-bound peoples. Part of the "checkmate in waiting" acceptance is probably best understood in this wider lack of mobility, a lack of a more highly Individualistic Self-Destiny mythology (which contains its own social ills). In "seeing the mate" in advance you to some degree transcend your situation by demonstrating that you understand it, you see the position on the board from above, you have that IQ...but you are also trapped by it, you accept THIS loss, in the name of having perhaps a better chance to win the next time. This isn't to say that dancing off the 5th round is the right thing to do, in any particular fight, or even to say that the practice of the 5th round in today's Muay Thai doesn't need to substantively change, it does. But it's to explain the logic of it. Today's Muay Thai in Thailand is trying to take the big name Gambler's thumb off the scale, not an easy task because gambling itself is woven into the seriousness of matches, a fighter's identity, and the passion for Muay Thai itself. It's instead to try and explain the nature of some of the thinking that is beneath a 5th round performance. It is not just fighters taking a break "because they fight so much". It's locating yourself, positioning yourself socially in the game, a game you are ultimately trying to win. If interested in my thoughts on what I believe underlies Thailand's Muay Thai can see my article on the "6 Core Aspects" https://8limbsus.com/muay-thai-thailand/essence-muay-thai-6-core-aspects-makes

-

Well, I think that's the point. In this case it was the class, collectively, which resolved the German text. The point being, the immediate "dumb" that you feel when confronted with a language you simply do not know could be analogized to being locked in a clinch lock that feels "impossible to solve". Yes, it is at first blush impossible. You are dumb. But then you start building inches toward a solution...and when done in a group even more is possible. It's the communal construction of, and passing of knowledge. It's not one person "mastering" a technique (for themselves), or having special insight into the meaning of a text.

-

Wow, that is very good. Reminds me of this experience: I had a very interesting professor who taught Foucault, the notoriously difficult Philosopher with very specialized language. She started the class with a passage of an unrelated text in German (anticipating that nobody in the class understood German). She then had the class draw out meanings from the German, a language nobody understood. Collectively people offered the meanings of words or even sentences, exercising bits of pattern recognition through cognates and similarities between English and German. This was so interesting because the assumption someone has when presented with a language they don't know is to just shut down. I don't read German. this text is nonsense to me. But the class actually did a pretty good job of drawing out meaning from the German. It's exactly this response to willing to feeling dumb. You start at dumb, and then you realize that you aren't completely dumb. It was also a marvelous teaching progression. Foucault's very difficult terminology and very opaque text, when presented AFTER the German text was in comparison much more clear. The difficulties in (trans) English of Foucault no longer were paralyzing, making you feel dumb. It suddenly became a challenge. How much of this text can I figure out on my own?

-

Well, this is maybe the source of a fundamental misunderstanding of the more traditional approach. It is never just "an individual" learning stuff. The Thai Kaimuay is composed of social learning. Techniques are not re-invented by every single person, every single time. Instead they are passed down - but not through top-down (mechanical) instruction. They are learned by training against superiors (at times) from whom you mimic solutions. They are learned by imitating the more accomplished fighters, older, who are training next to you. The entire social group passes knowledge across its members, once you learn to watch and learn. It's not a guru of some kind "teaching" everyone the same mechanics, the same solutions. There is top down instruction at times, but it happens at a very young age, and it usually is composed of aesthetic guidance, posture, demeanor, etc, the framework through with solutions flow. The Thai Kaimuay though isn't really something westerners can expose themselves to at a young age. But yes, there is no guarantee that a single boy will figure it out. A Thai Kaimuay isn't making 30 champions out of its 30 boys. I suspect actually, that the powers of self-discovery, imitative solution making, self-motivation to persevere acts as a kind of filter on the 30 boys in the Kaimuay. Not only is it teaching the under-structure of the art, and developing elite skills...it is also weeding out boys without those possibilities.

-

Eventually figure it out, because it isn't endless. When Sylvie started clinching with the Thai boys she would face the particularly difficult lock of the gym owner's son (who was pretty young, but also very strong). She suffered under this lock for a very long time. We guess it was maybe about a year before she "solved" it. I don't think he particularly liked clinching with a female (or even clinch at all) so he would just lock her hard (w/ a great technical lock I think he learned from his uncle, who has since passed), and would kind of stagnate the clinch and wait out the time. She just had to suffer it. I'm sure once in a rare while someone would go to her and show her a counter, which she might try (and the boy would just counter lock the counter), she got a little bit of information, but it honestly was a full year before she solved the position. People might think that a lot of that year with the boy was wasted. It wasn't. She had to learn to relax in that lock. Nobody was telling her "Relax!" "Relax!" (which was the proper thing to do). She had to struggle against it. Fail. Get seriously frustrated. Dread it. Almost give up. Suffer it. There was no way "out" of the lock. It was a death sentence. It was what you call "endless". But, think about the things she did learn. She learned tons and tons of deeper principles of Thai clinch. The answer wasn't a mechanical solution to a mechanical position, though it could certainly have been taught that way. When he does THIS, do THAT. And now, try it again and again and again, until you get it. Yeah, you could do that. No, she learned the nature of Thai clinch at an emotional level, at what it took to take...and eventually figure, when someone is dominating your will in a position you do not understand. This was a huge lesson in technique, and in clinch development. It gave the tools not in how to solve THIS position, but how to solve ALL positions, and how to properly comport yourself in Thai Clinch in Thailand (which has very specific aesthetic demands, from a judging standpoint). The result is that she probably is the best female Muay Thai clinch fighter in the world, at this point. Not because she has some kind of "technical" encyclopedia of "answers" to "questions". I mean, she does have a pretty big technical understanding; but beneath this she has a much deeper understanding. She, over a year of frustration, developed great resources within herself. Emotional and mental resources, but also tons of micro-physical, technical ones. Slight ways of turning the body to just delay or retard the endless lock (because you know its coming). Even though the lock would get there, even delaying it, slipping it for a moment, was a victory. These micro movements play into all other kinds of solutions to other positions, because SHE invented them, improvised them out of necessity. Because the fighter invented them they become part of your style, your language. They are like the micro movements that a surfer makes on the board, it only comes from riding the waves, endlessly. She learned to start to deny primary positions which would then result in the lock, counterfighting the lock before it even comes to be. She learned to eventually micro-wiggle out space for herself, when locked. Or to score when locked. Or to minimize the visual impact of the lock. All of it born from frustration, and lots of "endless" toil, which might seem to not have any real purpose. She learned to solve a very difficult puzzle, importantly, a puzzle that was put on her to control her in a social space. The solution had to be gained on every level. Now, if she had only been in the gym for a month, and a Kru had seen the lock and walked over to her and told her the antidote. Hey, when he does that, do this! And she practiced it over and over. Maybe they even would use the boy to set up the position, so she could practice the solve...and THEN she went back to her gym in the West and face smushed the hell out of anyone in the gym who would try to lock her (much less skilled than this Thai boy), and even defeated any attempt to lock her in a few fights, this would be considered VICTORY! But these are very different things, very different levels of knowledge, and importantly, very different experiences of the art of clinch. Yes, you can say there are LOTS of reasons to gain Knowledge #2, to be used in lots of circumstances, but Knowledge #1 is - at least to me - where true value is. Not just because it's more effective, in the long run, but its because its more meaningful, its more complete, more connected to oneself.

-

I'm not really interested in whether someone is "cheating" in a sportmanship sense or not. When you "hack" a process you are changing the process. You are trying to extract the benefits of a process by other means. Very often "hacks" are perfectly necessary and warrented, especially when discussing developing "Thai" techniques, simply because the original processes of their development are not even available to you. Many of these processes are not even available to Thais today. But, if there is a "cheat" it would simply be representing the "products" of two different processes, as the same products. They are not. If a traditional recipe is to make a stew over 3 days of cooking, developing depths of flavors, textures and in the end meaningfulness in cuisine, but someone cleverly decides they can "hack" the recipe, and make the "same" stew in 30 minutes, by identifying the spices, this certainly is a possibility. But they are not the same stews. Attached to this, there might be very good commercial reasons to make this 30 minute stew for sale in a series of businesses (profit margin), and even to advertise this stew as the traditional one. Yep, you can do this. But, noting the two different stews also holds value. If the old process of stew making is lost, we also lose the stew itself. It will simply disappear. In the case of Muay Thai, the advanced level of artistry and the superiority over the fight space will no longer be reachable. Our biggest focus has been what is largely a misunderstanding of what even Thai technique is AND how it is developed (it's not developed THROUGH precision-hunting, though it expresses itself with precision, for instance). The reason for this misunderstanding is how it has been historically exported out of the country. Its important to keep track of these transformations. It doesn't mean it is wrong to learn in all kinds of other ways, or to "hack" the longterm processes for all kinds of other uses. What I'm really concerned with is only when the "hack" (a radical change in process) REPLACES the original process, and starts to represent it as authentic. The reason why this is a concern is that if it becomes replaced in the mind's eye of the public, efforts to preserve (and respect) the original recipe and keep it from vanishing will fall away. If someone's aim is to beat everyone in their weight class in a particular talent pool, or whip everyone in their gym, or protect themselves on the street, or mix some Muay Thai into MMA there are TONS of ways to learn skills and attempt to deploy them. I would not criticize any of those projects, under those aims. They just are not - in my opinion - in the tradition of the high art, and do not result in the quality that distinguishes the absolute beauty and effectiveness of the Thai tradition of fighting. But, this goes not just for the West. Thailand itself is losing its own connection to those processes. Thais themselves are becoming less effective fighters. The change in process is pervading.

-

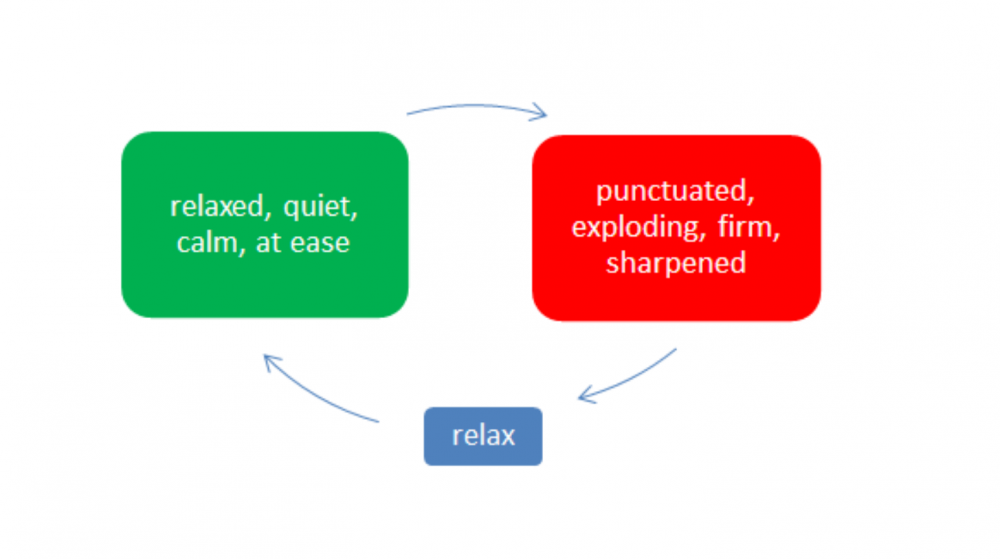

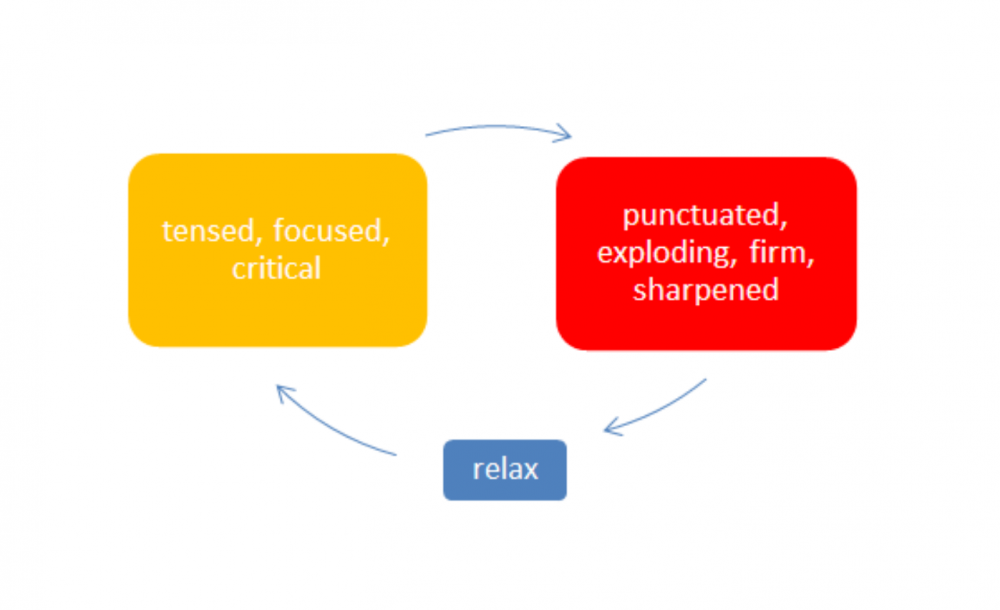

This is a very helpful article on the subject, if you'd like to understand our perspective: The Slow Cook versus the Hack – Thailand Muay Thai Development https://8limbsus.com/blog/the-slow-cook-versus-the-hack-thailand-muay-thai-development And this article as well: Precision – A Basic Motivation Mistake in Some Western Training https://8limbsus.com/muay-thai-thailand/precision-a-basic-motivation-mistake-in-western-training with these graphics:

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.