-

Posts

2,274 -

Joined

-

Days Won

502

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

If anyone wants to dive into my thinking on how to view the logic of possibilities of gender in female fighting, this is my essay to read, written 12 years ago: Wasps, Orchids, Beetles and Crickets: A Menagerie of Change in Transgender Identification This lays out the full Deleuzian, Guattarian, Wittgensteinian philosophical argument of why we are vastly underrating what is possible through female fighting projects and careers in Muay Thai. To be clear, Muay Thai is not the subject of the essay in any way, but the underlying argument and analysis is directly applicable to Muay Thai and gender. In short, if the analogy is not apparent, when female fighters - perhaps especially western female fighters, but also some Thai female fighters - take on the "clothes" of Thai hypermasculine performativity, this is necessarily the forming of a trans-gender assemblage. What is possible in these kinds of assemblages is infinite, and not reduceable to masculine or feminine essentialities. The most important - and potent - passage in perhaps all of Deleuze and Guattari's writing (cited in that essay linked above) is this, along with my explication: For, the body of a racehorse goes beyond our classifications of kinds—though these too demarcate the kinds of experiences a racehorse can have, for instance the experience of mating with a workhorse. A racehorse will likely experience things in a manner no workhorse will come to, while the ox and workhorse will have a community of affects historically determined across species. The body without organs is this veritable capacity to be defined through intensities experienced in particular ways; and from these intensities be able to disorganize from one’s history (deterritorialize), and reorganize in a line of flight, “jumping the tracks” of code so to speak, into new possibilities of material assemblage (reterritorializing), just as the orchid becomes an orchid-wasp. By extension, it invites us to see that, depending on how you slice the frame of reference, a serious western female fighter, and a serious Thai male fighter could arguably have more in common, than an imagined cosmopolitan Thai business man (who will never see the practice ring) and that same serious Thai male fighter. The workhorse and the ox. Gender, or any single taxonomy, is not the final frame of reference, and much more interesting things happen and are possible when we look to the specific assemblages being formed. The oxen very well could play an important part in the preservation of the most important values to be found in the art of work horses. Racehorses on the other hand may not. The ultimate analytical questions are: What is the affective capacity of intensive parts, and what are the comparable relations of extensive parts?

-

Let me quote the full paragraph, highlighting what I felt were the operative concepts and phrases of what you are saying. This was just my take on it. I see a lot of categorical thinking here, metaphysical claims, that seem to overtly exclude the possibility that this is just historically contingent patriarchy. I'm not sure at all how this can be read otherwise. This will "always" be the case, and women will "always" have this status, not because of the opinions of people, but because that this is essential. Also, please, just keep in mind that we had come to an agreement of what the values Odyssean and Achillean mean. You took these from my writings, I should have a sense of what they imply. Achillean is much preferred. Odyssean is really a kind of fallen state, at least by my original framework. So when you say: "...because of the odyssean ''foot halfway out the door'' of motherhood that is always latent to female fighters" you realize that you are also describing my wife, who is a female fighter of intense commitment, right? You seem to be arguing that she, and women like her, will always have the latent (and justified) position of being "halfway out the door" because of their ability to bear children. Given that we just had agreed Achilles > Odysseus, in what way should this not be considered a slight of her (and all other serious fighters?). If you scroll up to the top of this post and read the original study "Making Fields of Merit" attached and cited, very similar debates such as these surround the issue of whether seriously dedicated women should be able to ordain into monkhood (while only perfunctorily dedicated men regularly are). This is not me being sentimental about my wife. This is the very subject of this post. Scholars cited in that study debate about whether women are essentially "more attached to the world" due to the possibility of motherhood, and therefore essentially cannot take the same spiritual place that men can in the detachment commitment of Buddhism. It's a strongly analogical argument to the same one you seem to be presenting. I understand that arguing Philosophy is in its way its own world. It's the play of concepts, ideas, intuitions. But if Philosophy is to have importance, its because it impacts the Real. This is why I spooled out the kinds of conclusions that come from the positions you seem to be putting forth. It concludes with real, specific women, being barred from both recognition and opportunity, and other real specific men, being given the same, in a very asymmetrical way. Historically, this is done through these kinds of "eternal" "natural" appeals of that's just the way it is, and will always be, often with women finding themselves inherently, or latently, on the outside.

-

These two statements conflict. You can maybe see why it has lead to confusion. I felt you very clearly put your observations into the non-historically contingent category. Almost all sociological aversion is historically contingent. You seemed to very clearly preface your "halfway out the door" comments with an appeal to eternal things. You seemed to be claiming not a personal belief, I agree, but really an appeal some kind of ultimate reality, which will "always" be the case (not dependent on history). You seemed to be arguing that no matter how history proceeds, these eternal things about women would ground sociological aversion. In other words, it would seem to be argued that such aversion was permanently justified. That's what I have some quarrel with.

-

I let this slide by, but in sitting with me it kept tugging. I'm going to point out something that I think is important. You - I'm going to assume that you are male - are positing really a nearly ontological priority of your own theoretical home in the fighting ring, which would read as more real, more committed, than let's say, that of Sylvie, who has fought in the ring over 260 times. I'm going to assume as well that you have never been in the ring, or at least you have never been in the ring nearly as much as Sylvie, but you position Sylvie, who has been in the ring more than any westerner in history in Thailand, as categoricallly "halfway out the door" (Odyssean), apriori, when compared to you (or any other male) who very likely never have even put your foot IN the door. I don't mean to be rude about this pf course, and yes, maybe you have 100 fights under your belt, and you have put your foot in the ring quite a number of times, but...odds are, not. This really goes to the original subject of this post. That actual lived experiences of human beings are discounted and pre-framed, just along the justified lines of gender. Just as Thai Maechi, who devoted their lives to spiritual development, are put on a lower scale than even men who become monks, symbolically, for only a few weeks, female fighters who have actually put their lives (yes, lives, women have died through the ring) and their social capital on the line, under real violence (Sylvie has taken 211 stitches to the head), are discounted, under some strange logic of the biological capacity to carry a child. Rather than this capacity being something to their super-credit, instead it is to discount them, fighters categorically "half-way out the door". You duplicate the very contradiction which originated this post. I know you don't take this position strategically, but really, naturally. Which is part of the problem. That this division is seen as natural, instead of as constructed. This is problematic. You may think that I am pushing a technical point, but it is actually a concrete, real world point. Sylvie, who has several careers worth of fights and fought over 1,000 rounds in Thailand, cannot even touch the ring of Rajadanmern, for instance, because of this same logic. While there are western males of very little skill or commitment, even those who have fought their very first fight ever, at Rajadamnern stadium, because they, supposedly "have both feet in the door", by virtue of imaginary relations within their sexed identity.

-

You would be very surprised. When all is told Sylvie will be responsible, not only as a journalist, but as a fighter, for bringing forth the embodiment of the principles of traditional Muay Khao fighting and it's aesthetic aims. She, in her fighting, her ability to beat larger and larger opponents in the clinch (when westerns habitually and historically have feasted on smaller Thais) has actually inspired a generation of fighting to explore Muay Khao fighting. Perhaps not for you, but we have seen a very definite change in fighting style choices, the acceptability of clinch fighting tactics, the efficacy of clinch nullifying size, as readable, through her fighting example. You cannot separate this out from her research and documentation, because her fighting is also part of the documentation. But I think you are missing a piece of the puzzle. It will become more clear over the next 10 years. When a 100 lb fighter is able to regularly beat the best 120 lb fighters in the world (a goal), through Muay Khao fighting, this will save, preserve and celebrate elements of traditional fighting that otherwise would just be lost. Adding as well, her otherwise unheard of fight totals have already changed the game of how westerners fight and conceive of their fight careers. She has changed the measure. It used to be just counting more or less "fake" or manufactured belts. Fighters never even used to reach for large fighting numbers, repetitions. Now fight totals are part of the new way fighters speak of themselves. In fact fighters are making up numbers. Large numbers push us to think about fighting as Becoming, a process.

-

Perhaps, when talking about "fighting" as a broad category, but Muay Thai, in the classical sense is really at terrible risk, and very likely will just be subsumed by the western "beast mode" ideal. The Golden Age principles of the kinds of "eternal dynamics" you might seek, already are being rather thoroughly effaced, or at least made mute or dumb. The reason why female fighting may actually provide an important role in "saving" Muay Thai proper is exactly because "fighting", more broadly, will be coded as "male", and therefore will be the site of commercialized, "beast mode", hybrid aggro-kickboxing's colonization. It's in the margins that the tradition will be preserved, because the tradition is devalued, and those in the margins are devalued. Exactly in that it took a little 100 lb female fighter in the west, Sylvie, to seriously appreciate the legends of the past, whose lives were already being significantly forgotten, and work to document them. It is not a coincidence that it was a female fighter who did this, and not a male fighter. The very fact that we are discussing Muay Femeu vs Muay Khao metaphysics, that we have the fleshed out identities of these fighters, and even the video of these performances, is because of a woman.

-

The only point re: Achilles and the Nak Muay Ying, is this: Like Achilles female fighters do not find themselves alienated from Being, but rather only from their contingent moment in history. Like Achilles they must find a language, I would argue an aesthetic language, a fighting rhetoric, in which to express themselves, within the heroic code. As might anyone need to do so, creatively, when their voice cannot be heard. There are other interesting pathways, in regard to feminine and Achilles. The occult story of the time he spent disguised as a maiden before he went to war, for instance, the role the feminine might play in the warrior spirit, etc. But that's aside from this main point.

-

I think there are some parallels. Achilles is the complete man, the archetypal man of war. Not only is he the most skilled, most unbeatable, but also is portrayed as coming from a time, a Golden Age of men and gods, in which the arts of speech, song and performative oath are high. Odysseus is the "modern man" who uses his intellect and cunning almost like a villain, in comparison. There is a sense of fallen-ness. At least that is the juxtaposition in the play Ajax. I'm not sure that it all matches up, but when we talk of the heroic, the charm of Achilles feels like the same kind of charm of the yodmuay of the Golden Age, in a very rough sense. Like, there are no fighters like this any longer. And I think for fighters like Dieselnoi, there is a generation before that, when Wichannoi and even perhaps Suk reigned, which feels like another kind of man who no longer exists. Ha. I don't know about that! Authority in such cases is never too good. But, it is cool that you have read into my past essays of life before Muay Thai when I took such a deep dive. I'm glad to have them connected. I find it super fascinating how deep the art and sport of Muay Thai is when seen through the philosophical lens. This was a very informing article about Old World masculinity in Thailand, and magic, which I really enjoyed. It helped shape my perspective on some of these things, including Thai concepts of magic, and a kind of old sense the West: Rural Male Leadership, Religion and the Environment in Thailand's Mid-south, 1920s-1960s by Craig Reynolds Rural_Male_Leadership_Religion_and_the_E.pdf Ancient Greek Love Magic and studies such as these helped ground my sense of magic in the roots of Western thinking. I think that any perspective taken on Thai masculinity and Muay Thai that does not incorporate a perspective on magic is maybe incomplete. I was talking about this with Sylvie after my last post and I realize that my own view of Muay Khao vs Muay Femeu has maybe missed out on this dimension some. Muay Femeu is not just a negating power of deflection, or evasion, but ultimately is about - I think - asserting a positive kind of power, a magic (where maybe magic is read as a more powerful technology, a technos) over the technos of the other. I seem to recall that in the original poem lines that captured the fighting superiority of Naikhamtom before the Burmese, it was accredited to him the enchanting power of his Wai Khru/Ram Muay, which bedazzled his multiple opponents, not just his skill. You also get the coincidence of magic and masculinity in the story of Kuhn Pan, a story Sylvie has really fixated on, the great warrior/monk/mage/Don-Juan of the epic. I think you also get a sense of that magic in the nickname of Karuhat, Yodsian, which is really untranslatable. The Great Master, the High Guru, the Superstar, maybe even Midas Touch, not too far from some of the Hong Kong movie fighting masters who possessed magic powers and spiritual powers, in those wire-fu movies. This was a really good book in understanding the relationship between magic and masculinity, and spirituality in Thailand: The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand by Justin McDonald It does a really good job of outlining the kind of syncretism that we mentioned above, the old animistic beliefs, and the overlay of State Buddhism. If I recall the author suggests that this is Thailand's capitalism and commercialism's way of digesting multiplicity in a postmodern world. But, the figure of Somdet Do, one of the great monks of the 20th century, embodies some of that magical/man masculinity. For me, this is why Aesthetics matter in Muay Thai, and they should matter. Aesthetics, like notions of magic, enable one to draw on the pre-rational affective forces of "Man" (in the humanity sense, put in the figure of a man). Spinoza's maxim: We do not even know all the things a body can do. The affective powers a fighter draws on, through aesthetics, go beyond the rational of exportable techniques. It's all the connective, inspired tissue that makes it a living art, a magic, and that magic is what transports and raises up the audience outside the ropes. The question is, starting back at the beginning, why cannot women also possess those powers and position of transformation and control? There is no doubt a great genealogy to this question's answer, but I sense it is not foreclosed. That it is possible. And maybe that the future of Muay Thai may depend on it.

-

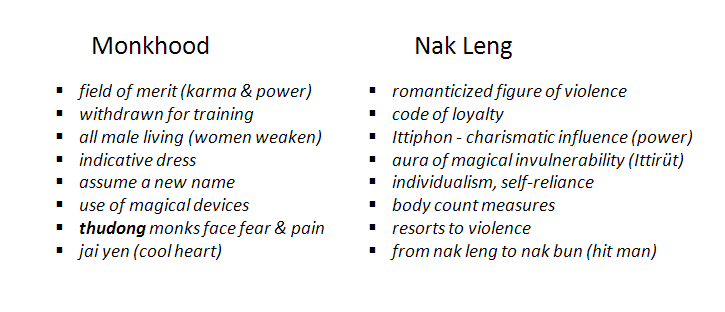

This brings up a very interesting parallel. One of the characteristics of yodmuay, especially femeu yodmuay, is their charm. Karuhat and Chatchai complained that the superstars of today no longer have charm. What empowered Samart, perhaps more than anything else, was his charm. This is a list Sylvie and I compiled from Peter Vail's article on the hypermasculinity of the Muay Thai fighter, borrowing from the image of the gangster and the monk. You can read about that here. I want to bring out that the "art" of femeu fighting isn't just a pretense, but it also has a kind of mysterious power that is like magic. You get this in Ancient Greek thought as well, where the artfulness of a person's speech contains a kind of magical control over you. Persuasion is magic. This is why seductive women are not to be trusted. Or someone who could make elaborate plans. Odysseus was "the man of many turns". On the nakleng side above you have "Ittiphon" which is just this kind of artfulness, the "aura" of someone, their power, and it was linked to their unkillability, their Ittirut. Klaew, Dieselnoi's Godfather manager was shot with endless machine gun fire with his magical protective amulet in his mouth, for just this reason. I would suggest that the aura of the femeu yodmuay contains this kind of magical sense of power. The reason why Samart can just dangle his arms and float around when Namphon is rushing at him, is not just because he is displaying self-control, in a Buddhistic sense, but also because he is displaying that kind of Ittiphon and Ittirut, his charm and invulnerability, which strongly partakes in that polytheistic/animistic tradition of beliefs. He is jai yen like a monk, but he is also magical like a monk (the great monks of Thailand in the early 20th century were known for their magical knowledge and powers). So you touch on something really interesting in the dichotomy. The artfulness of the femeu yodmuay is not just a kind of rarification of the Self, but the skill also creates a positive (effective) aura of magic, which draws on the older beliefs. You've helped me work towards the positive assertion of the Muay Femeu fighter, the assertion of power. But not physical power.

-

I would be wary of the opinions of the East from a 19th century European, who had his self-centric problems with race and stereotypes, to be sure. This does sound pretty reductionist to take his lead, but it certainly is a line of thought as well. Nietzsche probably knew very little of the lives of actual Buddhists, and all of it filtered through the prism of ideology. There is an ascent being performed in the Buddhistic ideals of self-mastery I would insist, which are reflected in the scoring asethetics of Thailand's Muay Thai. The artful matador is ascending over the bull, in one way or another. The bull of the Other, or the bull of oneself. The bigger debate seems to be about the bull. The bull is both blind instinct, in the cul-de-sac of its circuits and drives..."dumb", and also the progenitor of its own brilliant, un-guidable Becoming (...perhaps). This Self-Mastery, owned in the Buddhist ideal, is a potent path. I remember talking about Samart with Krongsak (a powerful, forward-fighting, Muay Maat fighter who drew with Dieselnoi). Krongsak nearly spat out disgust over the very accomplished femeu fighter Robert of JockyGym. All he does is run. He's not even a fighter. Its as if he was saying, he's not even a man. But, when he turned to Samart his eyes melted. For Thai fighters of the time nobody moved like Samart. Nobody existed in the space like Samart. He just shook his head in awe. (He also humorously said, when asked who would win between Somrak and Samar, "What promoter would book that fight? Who would pay a ticket to fall asleep!"). I'm just saying that if we are really going to get a handle on this dichotomy you can't reduce this incredible beauty of Samart, the femeu ascension, to just a "civilized slave morality". This is a performed transcendence that was very real in terms of violence in the ring. We have to account for the effect of Samart...or, you can replace Samart with someone who is even an more interesting aesthetic fighter, Karuhat. I realize that you are just free-wheeling in associations and ideas, which is, after all, where lots of good perspectives can come from.

-

One should say, also, if talking about the archetypal dichotomy of Muay Khao and Muay Femeu that many Golden Age Muay Khao fighters will really complain about the clinch fighters of the present era. They will complain how the game has become just a strength game, that all the art (femeu) has been lost in Muay Khao fighting. So the carriers of the High Art of Muay Khao, who themselves were demoted in the ideological pairing, use the same qualifiers to complain about the Muay Khao fighters of today. I'm not saying it isn't a fair criticism, it is for real and accurate I believe, but it is ironic to hear legends of the sport who were downgraded, aesthetically, use the same ruler to measure the next generations.

-

This. Totally. What is so interesting is that for decades now, with the fight lost to history, Samart losing to Dieselnoi was but a blip in his career. But when the actual fight video surfaced you see Samart being basically destroyed by Dieselnoi, totally overwhelmed in a way that had never been recorded before. Samart's sheen of the undisturbed fighter completely fell off. Before that video surfaced it wasn't even questionable who the GOAT was, but then it became questionable. Yes, you see the size difference, but you also see the art in Dieselnoi. And you see that Samart performed much worse than, say, Chamuakpet did facing even greater size differences like Sangtiennoi. The entire "story" of femeu inherent superiority falls away a bit, like a myth, because honestly the only people who saw that fight in the stadium, actually saw what happened. The aftermath of that fight, one would think, would have catapulted Diesenoi into GOAT status, the Muay Khao becoming proved itself, it won the eternal battle. But instead Dieselnoi said "No one would choose to have my life". Samart went into further glories, then movie roles, singing performances. The princely becoming continued its ascent. One cannot also, in this dichotomy escape the real sense that the poor and rural lay on one side of the Becoming divide, and the educated, urban, cosmopolitan on the other. It feels as if a myth is at work. An eternal myth? Or a particular ideological one? There is a very interesting gendered quality to Muay Khao vs Muay Femeu, in how fighters (and probably fans) think of it. Dieselnoi will joke and giggle, saying "Samart hits like a girl" (they are very, very good friends). I recall Samson Isaan, when he filmed with Sylvie with Karuhat present, would imitate a Muay Femeu fighter, dancing away like a girl, waving goodbye in an effeminate way. The "art" of Muay Femeu can contain strong feminine overtones when parodied. To the old school Muay Khao fighter the Muay Femeu fighter is not manly. While Karuhat would then make fun of Samson, pretending that if they fought Samson would just keep stumbling and falling, tripping over Karuhat's deftness, like a dumb man. There is an amazingly gendered (and also class) quality to this. But, going back to the original point of the post, women, female fighters, do not have access to this "feminine" (or maybe androgynous) ascension, by virtue of their sex. Female Thai fighters tend to adhere to the Muay Femeu aesthetic, for just this same gendered aspect, but it lacks transcendent powers for them. That's a really interesting thought. Maybe? I mean, they definitely appreciate the comeback, when it happens and succeeds, but there is a certain stench of desperation in even the attempt. A sense of shame, I think. Part of this though is that, for instance, in America and other mythologies of the Self, social mobility is highly encouraged and celebrated. The individual is cut free from the fabric of his/her conditions. Whereas in Thailand and the karma of community and rebirth, there is no such thing as the "self made man". Social mobility is quite rare on the whole. Facing a 5th round where you find yourself well behind in a fight, is a condition you have made for yourself, and I think there is a kind of embrace of that that creates a dignity, at times.

-

Yes, I would in no way suggest that Muay Femeu is reactive. The matador leads the bull. The whole point of Thailand's scoring biases is to affirm the control and dominance of artful imposition. What is interesting is that the classic pairing Muay Khao becoming and Muay Femeu becoming are in tension with each other, but also rest on a hierarchy of ascension. What is one to make of this really ideological and even politicized hierarchy? Is the Muay Khao fighter necessarily "lessor", and if so, on what anchored basis? I like this.

-

Here is the great ideal hero Rama (Vishnu) in the Ramakien, perfectly balanced as if in repose, firing his deadly arrows. This is Samart and his dangle-arms: How does one balance out, or rectify the continuous becoming of Dieselnoi, that tragic joy of affirmation, which counters the "beast mode" of negation, and the Princely cancellation of "beast mode" clashing, found in the elevation of Samart and figures like Rama? Are these the twin, and perhaps irreconcilable philosophies of Transcendence and Immanence? In this famous photo of Samart and Namphon, you have the princely transcendence of the future movie star Samart, and the bloodied Muay Khao man from a small Isaan town, cut by "intelligence" and "art" (I use these descriptions to bring out the dichotomy of judgement, not because they are real or fair). Ironically enough, Namphon's little brother Namkabuan would go onto to somewhat fuse these two aesthetics, the handsome, dashing technical fighter, and the relentless, explosive Muay Khao stylist: Interestingly, when we talked with Samart he told us, quite proudly, "I have never lost to Muay Khao" (despite losing quite dramatically to Dieselnoi). These are very loaded and powerful aesthetic judgements.

-

I can really buy into this at a kind of fundamental level of philosophical critique of the west and "beast mode" negation. But...I might have some difficulty making the pure equation between "chon" and affirmation. I mean, when you write: This really communicates a great deal of what you can FEEL off of Diesenoi when you are right there in his presence, to this day, a kind of tragic joy of affirmation. It's incredible. But, in Thailand there is also a kind of laddered critique of "chon" that is built into the scoring aesthetic, and the ultimate eternal battle between Muay Khao (chon, the bull) and Muay Femeu (su, the matador). What is so incredible about the Samart vs Dieselnoi fight, and finding it after all these decades, was how definitively the Muay Khao fighter just dismantled and broke the illusions of control of the fighter who is otherwise regarded as GOAT in style. In Thailand the Muay Femeu fighter, all things being equal, will always be more esteemed than the Muay Khao fighter. As Thais may say: Animals "chon" (clash), humans "su" (fight). So while there is a kind pan embrace of fighting "chon", there is also a scale on which it is judged. I always think back to this fight between Samart and Namphon. Namphon was one of the better Muay Khao fighters of his day. We have only a highly edited version of the fight, but from this fight edit it is almost impossible for me to see where Samart won this fight. It is clear that he did, you can see the frustration and resignation on Namphon's face, but it looks like Samart just "dangle-armed" his win. He went into a theater of play and superiority, and this theater (and his reputation) just stole the show. (You can see Samart trying to do these same dangle-arm tactics in his loss to Dieselnoi and his final fight vs Wangchannoi, but where they just appear as lost attempts at dignity): Samart in some ways is Vishnu, the conquering god who does not break a sweat, who with his lazily flung destructive arrows vanquishes demons. He embodies the "Bangkok" courtly Muay Thai that claims almost moral superiority to the Muay Khao, lower class clashes of the Muay Khao fighters of Isaan. He is princely. Almost all Muay Khao fighters have to fight against the stigma of just being "chon" fighters (low IQ, super strong and enduring, work animals). Dieselnoi has to explain how he was an accomplished, strategizing fighter. Chamuakpet is named "Mr. Computer Knee" to emphasize his intelligence. Elbow fighters have to use elbows artfully, and not with too much force or repetition (this is one reason why Yodkhunpon's career is vastly under appreciated by Thais, because he didn't). All of this is to say is that as much as Thailand celebrates a "chon" of fight culture, and an incredible tragic joy of affirmation, it also has a parallel path, a secondary channel, which overlays a story of transcendence, which also is quite hierarchical, political and ideological. But, you see this not just in Thailand or Muay Thai. The same thing played out between the "working man" Joe Frazier and Ali in western boxing.

-

There is an additional observation or note when taking up the maturation process of Thai boys through Muay Thai, and monkhood regimes of self-control. And that is if we take them to be parallel developmental paths, it perhaps sheds light on something that has always mystified me. Former fighters who fall to drink, who become alcoholics, have serious social stigma attached to them, even from within the community. As a westerner this just strikes me as just another vice, common among any in the population...but alcohol in particular seems to have an excessive strain to it. For a long time I just took this to mean that alcohol in its history in the culture just developed certain associations. There are legends of the sport who just became slotted very low, socially, because of their functioning alcoholism. It never quite added up. But, if Nak Muay are held up and esteemed, in the art, in part because of the very same self-control values that monks are idealized with (by degrees), then the fall from grace, the contrast of control vs a lack of self-control, just might really feel morally stark. We think of these great fighters and are like: How can you forget with they were!? (and in a way, still are). But, if you had a great monk who then at a certain point didn't abstain from celibacy in a vivid way, you really would not be thinking back to what a great monk they once were. Instead you would just get a very strong feeling for the depth of the fall. I'm not entirely sure about this, but it does lend itself to this analysis of value through displays of self-mastery and control. And the social shame that comes with falling from those states.

-

I know you are being cheeky, but just to be clear, it isn't actually the adult language, it's the part that begins.... Usually, anything that begins "not trying to be an asshole" and then follows with profanity, well...you know, is lacking in tone. I'm just trying to keep it all cool. If you want to cuss, curse, bust out all kinds of language in a friendly way, go for it. Sylvie and I are pretty sailormouth when it comes to enthusiasm.

-

To add to what Sylvie is saying: But, they are connected, because when your body folds, you can appear affected even if you don't show it on your face. So being really aware of your ruup, or disciplined in it, can help you appear to be ning. You can still be ning if your body folds, just in how your play it off, your continuity, your energy, not becoming mad, showing pain, or being hyper-aggressive (emotional control), but having great ruup supports the sense of ning.

-

I really hesitate to jump in here because you and I have very different frames of reference, and a great deal of what you assert just doesn't jib with what I know and experience, but I might as well give it a try... this just isn't what padwork is, or is for in Thailand. Yes, gyms that handle a lot of westerns do start molding padwork as a kind of simulated fighting...because they are westerners, and they often lack basic rhythm or responses...and, importantly, westerners like it. But this just isn't what padwork is for in the building of Thai fighters. Padwork, originally, was designed to "charge the battery" (as Kaensak put it) leading up to a fight. It's pounding out fighting shapes, building endurance and explosiveness. It isn't really a "teaching" mechanism. It's kind of become one for westerners, because gyms are changing, but this isn't what it really is for. Thais don't need to "simulate sparring", well, because they spar. If there are any teaching, or leading aspects of padwork, traditionally, maybe for developing fighters its about rhythm, posture, constancy, spacing, in the exercise of power and endurance. No, padwork really isn't "simulated sparring", at least in the core of it. Westerners do experience this "simulated fight" quality in Thailand, and then bring it back to their gym and mark it as "very Thai". And, I do think that for westerners who do need a lot of developmental experiences, it's a very good thing to try and bring out the "fight" energy in their Thai trainer, who usually is an ex-fighter and probably pretty bored with their endless rounds. Its a very good thing. It's more fun, etc. But no, that isn't really the purpose of padwork, classically.

-

I really don't mind the turn to metaphysics here! And I like how you picture "beast mode" as a negation, while traditional Muay Thai as an affirmation. There is something genuinely Dionysian I think about Thailand's traditional celebration of the art (and I suppose something of Apollo of course). It is that ascending spark, through the hierarchies of Being, or at least it feels like that. It is no accident that a Muay Thai fight begins with a dance.

-

Ali played a lot with "just looking tired" in an exaggerated way, to buy himself time to rest, or to create dramatic reversals when he really hit the gas again. Instead of tired, great femeu fighters like Samart or Somrak instead look disinterested, or like they aren't fighting hard. They still have ruup, in the sense that they aren't staggering around, but instead they make it all look like it is effortless, and nothing is effecting them.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.