-

Posts

2,264 -

Joined

-

Days Won

500

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

Historical Spheres of Influence in 20th Century Muay Thai This is only a very rough sketch from compiled reading, but thinking about spheres of Muay Thai influence an historical trends. If I state things as fact this is only a parlance of my assumptions. On some topics I've read deeply into the history, in others I have only brushed over (for lack of English language record) and may make speculative leaps. It is hopeful that this informs, but not as an expert. Much more to set a broad picture, a framework, for real historical telling. It seems to me that any history of Muay Thai should include all 4 spheres. above, Chaiyut, a powerful Sino-Thai gym owner and promoter from the 1955-ish, son of Tankee who was the same before him (found via Lev). "The one on the left was an international boxing champion at Raja, on the right is Saipet the Chinese fighter who held the 126 title until he moved to boxing." Left: Sarika Yontharakit, Right: Saipet Yontharakit* Chinese The Chinese, who have been in Thailand close to 1,000 years, and perhaps even 2,000, at the turn of the 20th century were a huge political and economic influence upon Bangkok, and Siam in general. Chinese triads and secret societies (read here) ostensibly ran all gambling (which around 1900 made up 25% of the Siamese government's revenue around 1900 though vice tax farming), as well as large sectors of the economy such as the Chinese workforce on the docks of Bangkok, rice-mills, saw-mills, and tin mining in Phuket. Read Gambling, the State and Society in Siam, c. 1880-1945 here. When gambling was outlawed in a series of moralizing legal steps by King Vajiravudh in the 1910s, this was probably largely to fundamentally break off the government's dependency on Chinese financial power, or at least the secret society vice economy layer of that financial power. Notably, the King had to back off the outlawing of Bangkok Muay Thai gambling, as the sport's popularity took a nosedive. It was fundamentally a gambling sport even in 1920. The exception of Bangkok Muay Thai legal gambling goes back over 100 years to this time. The influence was not of Chinese fighting arts, as far as we can tell, though there were some Muay Boran vs Kung Fu fights back then (1921, below for instance), it was likely the consumate wholeness with the Chinese syndicates controlled parts of Bangkok economic culture. Even in today's Muay Thai almost all the large Bangkok promoters are Sino-Thai, and no doubt much of the "gangster" aura around Bangkok Muay Thai through the decades may have been due to this Sino-Thai lineage, tracing back well before 1900. Between these eras the Chinese population of Siam also underwent great discrimination, and there were immigration waves from China following the Japanese wars on China and China' own civil wars. I do not know enough of Siam-Thai history to follow the politics of the Chinese in Siam, but it would be worthwhile to trace this, from turn of the century secret societies and tax farms, to the Sino-Thai predominance in contemporary Bangkok Muay Thai. Was this development continuous, or did it suffer breaks in position and power within the culture? Most of the Western conception of Thailand's Muay Thai comes from the Bangkok Stadia, promotional scene, but almost none of this is understood through Thailand's Sino-Thai history. above, General Tunwakom, a naval general and teacher of military Muay Lertrit Military & Police Muay Thai and Boxing When King Vajiravudh, as prince, returned from his young-adulthood education in England at military college and other institutions, he was not alone in this trend of Siamese royalty and elites being educated in England in their youth, especially with a view towards military practice. King Vajiravudh's experience of British Boxing helped inspire him to reform Siam's Muay Boran upon the more "civilizing" practice of Boxing. This is to say, as part of a military education among the elite came the influence of Boxing. The organization of a National Police force brought with it a curriculum that included not only Muay Thai, but also Boxing and Judo. By the time Police run Rajadamnern Stadium opened Muay Thai had been reorganized to resemble Western Boxing in the Capital. Here, I'm not so much interested in detecting a direct influence of British Boxing on Thailand's Muay Thai, as to scope out a general sphere of influence that comes from military instruction (from foreign countries) and a certain relationship to Boxing. Boxing was taught in the academies, and prominent boxing leagues existed throughout the century, first probably on the British model, but then in the 1950s, under the influence of the US military which was taking an increased role in Thailand's military, aligning it within their own anti-Communism interests. In the 1950s the Siam Police force became incredibly well armed and trained by the US, and I believe by the 1960s Army and Police trained boxers filled out amateur and pro ranks in the region (Pone Kingpetch winning the first World Boxing title in the early 1960s). The Thai army ran Lumpinee and the Thai Police ran Rajadamnern, and by the late 1960s there were pro boxing fights on every card, something that continued until until sometime in the 2000s. This is only to say that there is a rather large, and also Boxing-infused, Military and Police Force sphere of Muay Thai influence which very few Westerners think about, or even have knowledge of. It's very hard to quantify or even imagine just how thoroughly this influence pervaded, as both the Army and Police are extremely esteemed, run the two National Stadia, and set a standard of excellence throughout the country. Even such things as very long running regimes for Muay Thai, one could speculate, likely came out of military training, on both the British and then American examples. (In fact it seems probable that in the American tradition of Boxing, long runs may have come out of US military practice.) Many of the biggest Bangkok kaimuay camps were headed by Police officers. The Police in Thailand for some time developed into its own border-policing paramilitary group, it is not quite how the civic Police may be in your own country. At times it has been like a branch of the Thai military. Royal Muay Thai This is not an insignificant sphere, though I won't sketch out much of it here - academic Peter Vail does a good job of outlining the discussion. Muay Thai holds a very prominent role in its political ideology, from its characterization as the force of the people that prevented colonization (unlike neighboring countries), to foundational stories of Royal martial prowess. Muay Thai has a very strong Royal history, and during the very long reign of King Rama IX his patronage of the sport helped lift it symbolically in terms of social esteem. This stands apart from, though no doubt also is braided with Military and Police patronage and development, in that this helps compose its signification in the culture, and grants to Muay Thai in the Capital a level of social importance that rises above the gambling stadia dynamics. The Capital of Thailand (and Siam) is a North Star of value, and Muay Thai has been embraced ideologically, likely for centuries. Provincial Muay Thai This is a Muay Thai that, in part, develops a far from the Royal, Military & Police and Sino-Thai Gambling cultures, in festival fights, themselves organized through gambling. Provincial fighting also culminated in indepdent major city fighting scenes, especially around the Golden Age. I write in some detail about the structure of this development, at least from my speculative view: How Thailand's Muay Thai Has Been Collectively Created Through the Wisdom of Local Markets and Gambling. Because provincial fighters fought in the Bangkok scene, and train both as Thai military and police, and even fought in the military boxing leagues, this provincial development did not occur in isolation (though it was likely highly accelerated with the building of railroad lines in the 1905-1930s, for the first time connecting populaces quickly over distance). Over the last century there was a flux of Capital and Military Muay Thai experiences and pedagogies fed back into the provinces as fighters returned to their homes. But, in thinking about the large spheres of influence on Muay Thai's development and practice there can be no doubt that a major one is provincial Muay Thai, not only in terms of Boran styles which may have reflected local, antique knowledges, but also in the very large number of fights, 10,000s that have occurred every year, going back more than 100 years, if not quite a bit much longer, the skill-tested, fitness landscape "laboratory" of its evolution. Included in this provincial history, though this would be its own branch of historical study, one would find the Muay Wat legacy of Muay Thai knowledge, the manor in which fighting techniques were taught in Thai temples, and still to this day are. Historically, there is likely a pre-modern legacy of magical practices and technical fighting practices that were braided together and preserved within the Wat. One could argue that the religious reforms that came with the fashioning of Siam into a modern Nation State, including the transformation of Muay Boran into a Boxing-influenced modernized sport, were in part to secularize the fighting capacities of Siamese subjects, moving away from the political power of regional Wats, and into a Nationalized Police and military force. The Wat connection to contemporary Muay Thai remain strong at the provincial, festival level. I discuss a bit of their relation to Muay Thai in this article: The 3 Circulations of Thailand's Rural Muay Thai - Buddhism, Rice & Masculinity .

-

Enjoyed watching Petchneung's grit. First fight of his I've enjoyed (not everyone's style is for everyone). Went to another country, walked through all the beatings. I could feel his heart. Hard to absorb that kind of loss at 19, but his toughness means a lot. Kinda ridiculous that the Raja belt lives in Japan, or even that non-Thais fight each other for the belt, but we are in a new era of promotional Muay Thai.

-

It was a pretty beautiful thing to watch Sylvie box yesterday, learning how to chase the Thai femeu fighter (something she's mastered in Muay Thai), at a completely different distance, under different rules. Unable to close and clinch she actually ended up getting caught in a defensive clinch, not having the Duran techniques of punching with arm control, it was just such a special thing. When you isolate like this, holes come to the fore. Everything is that 6-18 inches that pretty much every female (and many male) Muay Thai fighters ignore. Some combo through them, but its just a huge blindspot in everyone. Boxing happens in that blindspot, which is why (if you aren't just memorized combo-ing), you need eyes, and feeling feet. Sylvie has spent so much time fighting huge opponents, multiple weight classes up, she has a very strong instinct to brace for shots, to freeze. Boxing does not allow this, which is beautiful. The sport opens up, like an analytic, upon female Muay Thai, and for Sylvie origami unfolds a huge potential of being able to see and feel in those 6'-18", unlike almost every other fighter. It was very cool to see up on the rope. And, it was very cool to see her putting it on her in the 3rd and 4th rounds, her fighter's instinct coming on.

-

This point I was making about big gyms in Thailand with top active names, was also recently made by Gilbert Areanas when talking about Bronny (LeBron's son) training with LeBron. ""I don't wanna learn from a 40-year-old... I'm not learning what got the 40-year-old to his 40th year. I wanna see what LeBron was doing his first year." Even Thais at 23-25 are very developed and experienced "vets" of the sport, and are likely training very differently than how they trained as rising fighters, becoming the fighters they are. Also of note, a lot of older Thais are very drawn to Western "modern" training, if only because it is so different from what they have been doing for years, which frankly they see as boring. It also can keep them from having to grind, which mentally can be fatiguing. "Modernity" as its own allure in Thailand gyms, but does not necessarily make the best fighters.

-

The Origins of Muay Thai Clinch Fighting Through Indianization Bookmarking for later. Southeast Asia went through an extensive Indianization period, a 1,000 years (?), in which much of the royal court structure of governance, and Hinduism (the Buddhism) established itself in mainland SEA. It has been broadly likened to perhaps the Romanization of Europe. Aspects of the Indian caste system also established themselves. What has been little discussed (that I have seen) is the likely martial arts influence from India. Things like Thailand's Muay Thai and its Khmer and South China precursors are not really discussed, historically, in the contest of an Indianizing influence (even though quite late in this), in Ayuthaya, the Siam King had a personal guard of 200 Persian/Indian warriors. I don't have much to say on that, but for a while now I imagined that the wrestling portion of Siam's Muay Thai likely came from this very old influence from India. The oldest sport versions of Muay Thai (gambled) include the mention of wrestling. Things of note: Hanuman was famed for being a great wrestler in the Ramayana, and was even homaged to by wrestlers of India. The Indianized orgins of Thailand's royal structure, the sacred gods of Hinduism, if wrestling too was part of this cultural heritage, puts Thai clinch/wrestling in line with some of the highest forms of Siamese/Thai culture. There is a Burmese Indian form of wrestling (which more clearly marks out this influence). One wonders if some of the anti-wrestling Muay Thai rulesets that are often (rightly) described as anti-Judo (Japanese), could also be anti-Burmese in origin (a traditionally hated National enemy). Wikis to look up: In the Burmese state of Rhakine a form wrestling that is traditionally practices in the rural villages, and fought in festivals (sounds familiar). It has long been my thesis that sport Muay Thai developed in parallel lineages, one at the level of the Capital or civic centers of Kingdoms, with royal (and formal martial) auspices, but another at the level of the populaces, in festival rites of contest and social organization (gambled).

-

Saying a thing or two about the Patong Fight Night promotion. This is the creation of Num Noi who owns Singpatong gym in Phuket, and who has been behind some of the bigger high-profile farang wins at Lumpinee (before the rise of Entertainment Muay Thai), with both Damian Almos and Rafi in his stable of fighters. He has created a wonderful traditional promotion with strong production values, broadcast on YouTube. All the fighters (on this card) fought in the trad style, always with a distinct effort toward Thai techniques, even when their skills were not of the highest caliber. You felt like you were watching actual Muay Thai, and not some Western mashup. This was forwarding Muay Thai. Even at the bigger weights, in farang vs farang matchups, it made a huge difference in enjoyment. Instead of fighters holding their breath and letting go with clashing combos, they were trying to figure each other out, find advantages and solve disadvantages. There was actual narrative structure. In the fight before Dangkonfah's a Libyan fighter (I believe), in a close fight the 3rd round switched to Southpaw and discovered his American opponent had real trouble blocking kicks to the open side. It was a great adjustment, he found a weakness. Then the American (sorry, I don't remember anyone's names) started teeping his opponent's groin, repeatedly. Someone must have told him that this was legal (which it is), and may have even encouraged him (its poor sportsmanship, but hey, it can be done). It was something to watch the Libyan fighter fighter deal with this once he realized it was intentional. He got mad, switched out of Southpaw so he could go hard in his more comfortable orthodox. In a way, it had worked. The kicking advantage was lost. Between rounds, going into the 5th, he must have been told to go back to Southpaw and he did, and he regained his advantage. With some excitement he finally had pinned his somewhat enraging opponent in the corner with leg kicks, and you just held your breath. Would it keep kicking? Would this be a leg kick KO? The whole thing had tremendous narrative, even with the somewhat dirty play, because this is traditional Muay Thai, and fighters are forced to solve each other. It doesn't matter that the fight wasn't at some elite level. The fighters were well-matched, they were bringing the weapons they knew well, it was a wonderful dialogue of combat. If it had been Entertainment combo-ing over and over it would have been unwatchable (for me personally). Instead, it was a joy to watch. Muay Thai when it is properly fought has something to say at all levels.

-

We first met Dangkongfah 7 years ago, when she was on a festival card in Nongbuacoke (Isaan) that Sylvie was on. Her name is Nong Ploy (play name), she was 15 and came out of the crowd to spontaneously help corner for Sylvie. That is her in the Hawaiian print shirt, giving Sylvie advice in the fight. We watched her fight that night too. She was dynamic, and masterful at turning the fight at the right moment.

-

What a Fight. One of Most Personally Enjoyable Female Fights I've Seen in a Long Time I may not expect others to thrill at this fight as much as Sylvie and I did, but Dangkongfah vs Karolina Lisowska of Poland was just quite an experience for us to watch. A big part of that joy was being so familiar with Thai female fighters in Thailand (Sylvie has fought nearly 150 Thais, easily the most any Westerner has fought), so in explaining what made this fight so awesome for us I get to tell the story of Thai female fighters in general, over the past 10 years or so, so I can point out just how good Dangkongfah's performance was. As a sidenote, none of what I write is significant commentary on Karonlina, a fighter I do not know. Appreciating That Female Fighters, Understanding Their Development The best Thai female fighters, historically, but also still, develop their skills in the side bet circuits where local fight scenes in the provinces produce top fighters in a gambling milieu. The female fighters fight a lot, and the fights are very traditional in style (which is to say, narratively driven, balance, control and dominance being major scoring factors, purity of technique rewarded, and with clinch a significant part of all cards). Local top fighters travel around to other local top fighters in festivals, and the bet sizes go up. This prize-fighting scene produces highly skilled, complex fighters...but they tend to hit their apex around 14-15. That's when they are fighting the most frequently, training hard, and are actively being sharpened by the gambling. Once they get around that age they stop fighting so much (often because it is harder to find opponents, but also in terms of just the changing social status of young women). They can still be very, very good fighters, but they usually flatten out. In the past great fighters like Chomanee, Lomannee, Sawsing, Loma, and Phetjee Jaa came out like this. These are the yodmuay of Thai female fighting. In their later teens they might fight on the Thai National Team (amateur), but really in terms of development by 16 the peak of sidebet skill driving is missing (this side bet process is what traditionally drives the skills of male Thai fighters, well into their late 20s or even 30s, in the National Stadia. The next gen after the one mentioned above, because the side bet scenes have been eroding, haven't really produced the classic female "yodmuay", the one who takes on all comers, and has reached the apex level in the traditional way. Potential side bet yodmuay came through like Nongbiew and Pornphan, pretty strong fighters at 15 or so, but nobody reaching those past levels (Sylvie fought both of these fighters when they were at their apex, giving up significant weight). What ended up happening in this gen is that with the rise of Entertainment Muay Thai mid-level Thai female fighters, and some top level, from the side bet circuit were brought into Entertainment oriented training. A lot of these fighters who had developed a timing and narrative prize fighting game were newly taught bite-down and combo fighting (which is pretty foreign to them). Entertainment Muay Thai wanted clashing, so female Thai fighters (who were timing fighters) learned instead how to just come in with memorized strikes. Some, got good at this, and did well in Entertainment Muay Thai, but most floundered a bit. They were fighting out of their element, away from their skill set. Always the Underdog The interesting thing about Dangkongfah is that she rode this wave of opportunity in Entertainment Muay Thai, she began using combos and clashing, becoming recognized on (televised) Super Champ, which was somewhat promoting her as a Thai story, but she really wasn't pretty with it at all. She in fact had been in the Fairtex stable around with Stamp was taken in and began being fashioned into an Entertainment star, but Dangkongfah was not taken seriously, perhaps viewed somewhat as a backwardish Isaan fighter, from the countryside. What people didn't appreciate, and what Entertainment Muay Thai didn't really care about, about Dangkongfah is that she's a highly developed prize-fighter, she is really, really, REALLY good at managing a fight, in the traditional sense. She doesn't usually LOOK like she's doing much, but she is really good. So Dangkongfah was something of the Cinderella step-sister to Stamp at Fairtex. She left Fairtex, had some recognition on Hard Core (an Entertainment, small-glove show), and then got some revenge on Entertainment Muay Thai. The excellent Allycia Rodrigues beat Stamp for the ONE World Muay Thai title in August of 2020, and then one month later Dangkongfah faced Allycia for the Thailand belt (trad Muay Thai). She beat the ONE World Champion for the belt, not looking pretty at all in her combo-ish strking, but managing the fight with the brilliance of a fighter who had been fighting for prizes since a kid. It must have been a tremendously satisfying win. Allycia would then defend her ONE belt vs Janet Todd 6 months later. Around this time Dangkongfah also took the 112 lb WBC World title vs Souris Manfredi, in a fight set up basically with the aim of giving Souris the opportunity for the much desired title shot - there had been many roadblocks. Again, in a way that was probably frustrating to her opponent, Dangkongfah controlled time and distance, walking away with the belt. She's just such an interesting fighter, but to see it, to feel it, you have to have her in the traditional ruleset. When she fought Meksen in ONE Entertainment Muay Thai, fish out of water trying to trade wonky combos in that style with an experienced fighter, with some visible size, who will just combo cleaning up the middle. It was a blowout. Dangkongfah had gone up to Buakaw's Banchamek gym, which had worked with talented trad female fighters trying to help them fight in the Entertainment, Kickboxing style. Sylvie's long time opponent Nanghong Liangprasert (now using the fighter name: Nong Faasai PK Saenchai) was up there. Again, this seems to largely be trad teaching timing, narrative Muay Thai fighters how to throw Entertainment combos, so they can get fight opportunities in the growing Entertainment versions of the sport. There is another element to this story, and the appreciation of this beautiful fight (on Patong Fight Night) which is that some young Thai side bet fighters end up on commercialized gyms like Banchamek or Fairtex and start weight training and drilling combinations, but many others move out of their teen situations and stop training hard at all. They will be adding combos so they can fight and clash in Entertainment Muay Thai vs Westerners, but they will gain weight pretty quickly. By the time they are 18 or so a 51 kg fighter can easily be a 60+ kg fighter, facing Westerners. They will have added a bite-down style for Entertainment, but many are outside of the rigorous training that made them quite good when they were 14-15. This is enough to say, when we see a Thai female fighter on television, who was once pretty skilled and sharp, often someone Sylvie has fought when they were apex, and they have gained a lot of weight, the first thought is: Are they training hard? Are they running? Will they gas? And, will they just be throwing combos (which really isn't their deeper skill set)? The expectation is that they no longer are peak. This is what made Dangkongfah's performance so stunning, and so enjoyable...so admirable. She has gained a substantial amount of weight. She's only 22, but the guess would be that she was quite far from her peak as a fighter. She was NOT far from her peak...in fact this is probably the best I've ever seen her fight. We've seen maybe 5 fights of hers, including when she was maybe 13 in Isaan, we know her arc really well. She was so good. I feel bad for her opponent Karonlina because there is no way she could know how good Dangkongfah is. And looking at her she might have thought she'd have it easy. This was a late replacement fight. It was NOT easy. This is what I LOVED about Dangkongfah's performance. First, she was able to fight in the traditional style, which is HER art. So much praise for Num Noi (the promoter) for creating a REAL traditional show, right in the heart of Phuket tourism. You need a properly reffed, full-rules setting to see what Dangkongfah is, since a kid. But, what is even more cool is that wherever Dangkongfah is training they gave her a wicked jab. In fact she worked almost the entire fight through one of my favorite inner games for a fighter, Jap-Teep in combination. But these are not memorized combinations, this is using them in a creative game of timing, changing levels, intensity, feints. Entire fights can be fought through just these two strikes, and Dangkongfah is doing it at a very high level. She actually isn't teeping much, but her teep-fake is so hard (with the knee bounce) it makes the opponent bite. The form of that feignt is almost as good as a teep itself, changing levels. Just watching these two lead attacks, and the sharp quality of her jab was a thing of beauty. She had practically given up all together the wild combos she had taken up for Entertainment Muay Thai, she had returned to her timing art. This was very moving for me. By the 3rd round her jab and teep had subtly managed to change Karolina's fight distance, putting her "on the porch" as Sylvie and I like to say, exactly where Dangkongfah wanted her, so she could control, negate and counter. In the 4th Karolina figured it out, her distance was wrong, and she tried to walk through the porch, but it was too late. Dangkonfah is very experienced with this. She just muddied up the 4th with clashes and more jabs and teeps, (a big teep to the ground to establish stylistic dominance) denying any change in the fight. She is expert at spoiling the clinch, and it served her very well, draining away any chance for a change. It had already been decided in the 3rd, in terms of style and narrative, and she just used the 4th to lock it away. Then in the 5th it was a walk home with the lead in the trad style. This is how I like to watch fights. I don't really watch strikes. I see them like anything else, but I like to watch distance control and timing, the way the fighter manages these things. Also, even though she had put on significant weight, she looked FANTASTIC. She wasn't winded at all (maybe a little in the 4th round some of the edge came off?), she was incredibly light on her feet (lighter than in many of her past fights), she moved like an optical illusion, subtly shifting, driving, changing angles. As a basketball fan I have a certain weakness for very light-footed, super skilled big boys like Charles Barkley or Big Baby Davis (above). When athletes are big bodied, but display finesses, touch, speed and agility, its just plain stunning. And looking at her, it even seem possible that even though she's much bigger than even a year ago, she may be power lifting? She just looked fantastic, like even though this isn't a normie body, this is HER body, and she looked totally at home in it, even maybe apex in it. All these things together just made the fight unbelievably joyous to watch (nothing against Karolina who fought admirably). Dankongfah as the continual underdog, from Fairtex dropout to wild Entertainment combo-ist, here getting to do HER art, and with these beautiful new tools, tools of real Muay Thai, in a promotion that favors the trad art. And that she's found a place in her body where she just is being her, being free in the ring, in a non-trad body, using all her skills and instinct. Seeing this wonderful fighter having a place, a trajectory. It meant a lot.

-

I wonder if that is Nungubon's gym. Nungubon does have transfer over to Hongtong (the Hongtong boys are from Ubon), in fact I believe that farang who handles Nungubon's IG trains at Hongtong at times, if I'm not mistaken. More broadly though, thanks for such an informative, and personally grounded post to help others out Joseph, good stuff!

-

You could try Silk Muay Thai in Pattaya, which has a very openminded attitude, is organized around serious training, combines Thai style training with more Western concepts, the vibe is good, its a new facility, and there are Westerners there (which means bigger body-types). Daniel the owner is a straight up, positive guy. The fighters fight a lot, the excellent pad man Chicken Man (Kru Gai) can handle size. I don't think its a pricey gym. https://www.instagram.com/silkmuaythai/

-

Watching Orachunnoi vs Phetpayao (Phayao) from 1977 today. Phetpayao is "Phayao" the first Thai to win an Olympic medal, a Bronze at the 1976 Olympics in Boxing. Orachunnoi is in darker shorts. Phayao was trained by Arjan Surat (legend and friend, of Dejrat). He would win the WBC World Boxing title in 1983. Orachunnoi is 6 years or so his senior. Two legends of the sport. Orachannoi also was a boxer, though in the amateur Asian scene, nicknamed Golden Fist. Because both fighters are known for their hands, and involved in boxing I really was interested in how they would face each other. Phayao's lead fan-sok elbow, and even elbow combinations were pretty surprising, elbows flowing in his boxer's set. Orachunnoi just a wider tool box. The wide-sweeping low-kick and teep working combination. Lots of Smart side teep, and even a kind of sweep-back teep to the face (twice at least), and then in the 4th round he comes inside to do the dirty work with his hands. What a beautiful fight.

-

It's pretty awesome and amazing to be having the trainer of the legend Orachannoi, a now past legend of the sport, called The Poor Man's Champion, 60 years later Arjan Gimyu, who trained Orachannoi watching Sylvie's boxing at Rambaa's and saying that it reminds him of Orachunnoi, who was known as "Golden Fist", if only to be the reason that his memory came back to him. Orachunnaoi Hor Mahachai Arjan Gimyu holding for Kaensak back in the FOTY days Gimyu was a top Thai Boxer before he became a trainer, and was a stadium Muay Thai fighter as well. He retired from fighting at 44. He now hangs out at Rambaa's just watching the Muay. This post is just an appreciation of being in contact with these memories, and also something of the belief that Western Boxing has had a profound impact on Thailand's Muay Thai, and that Sylvie in boxing her first "official" boxing fight on Saturday, and training up for it, it touching those historical threads. Arjan Gimyu looking back on his own life, and those he trained, and kind of getting excited is pretty cool for what it is.

-

I feel like I've kind of resigned myself to realizing that I lived through the last of maybe classical Muay Thai, the Muay Thai of Rama IX, and it is just passing into another phase. Maybe it will bend back at some point, the country is incredibly resilient to foreign influence (though very open to it, as if it has developed an immunity over the centuries through that contact and impulse). I feel maybe less like we have to struggle to pull it all back into the other direction, away from its commodification, and more that I'm just so joyed to have experienced its final decade, to have seen it, and be living in that afterglow. I still hope to preserve as much from those final generations, hoping the seeds of that beautiful art are thrown forward...but at least today I'm more in a state of appreciation and thankfulness.

-

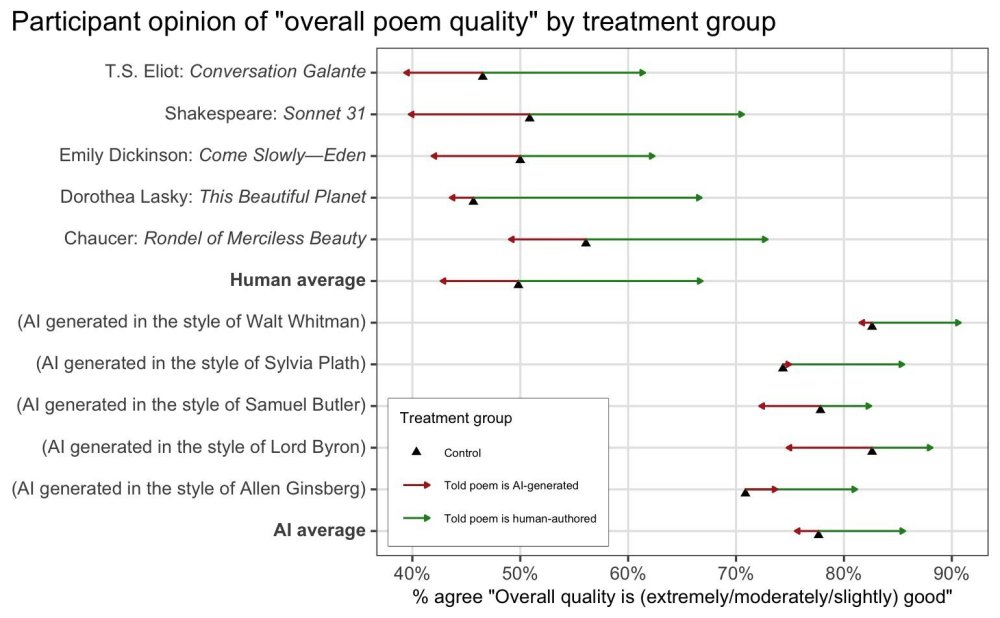

Muay Thai Rules The commercial generalization of a diverse art and sport into codified rules (legalization), is not entirely unlike AI generalizing living language into patterns...without actually understanding language. It moves from the specifically general, to the generally specific, via algorithm. This is to say that the specificity of a verdant expression, a concratized variety, then becomes refined as a specific generalization (a governing rule, laws), for the purposes of export, rules/laws not really involved in the generation of the concretized variety itself. Relevant graphic:

-

At times I think to myself "now, is a good time to dig into Sylvie's record". It's found here on Google Sheets, with links to every fight, estimated weights of opponents, details and notes. It's one of the most comprehensive and thorough public records of fighting in Thailand ever, if not the most. The reason why I occasionally find myself cycling back into it is that its a record like no other in the history of Muay Thai fighting in the world, especially among female fighters, so it is quite hard to assess. Comparison is how we like to values and in many ways Sylvie's record is without comparison. Also, if the work is not done, the story is not written, it will fall to forgetting, and sport survives through remembrance. One of the biggest issues of comparison is just its sheer size. She is coming on 300 fights fought. She likely holds the record for most documented fights fought by a female fighter (an amateur boxer, I'm sorry I don't have her name at hand) is very close to the same. She definitely is the female fighter with the most documented pro fights, regardless of combat sport, there isn't really a somewhat second place (that I know of). And, most of her opponents are opponents you would never hear of unless you are extremely knowledgeable about Thailand female Muay Thai (from 2012-present), about as niche a combat sport knowledge as there is. Far from international coverage there are 1,000s upon 1,000s of Muay Thai fights fought, not near the capital, as Thailand is the home of Muay Thai and fighting in the sport is culturally robust. Each region has local champions or elite fighters, many of which would not find their way to Bangkok (particularly before the recent rise of Entertainment Muay Thai and Soft Power initiatives); there is an entire network of side-bet (gambling) fighting throughout the provinces, in their cities, towns and wats. Some of these female fighters find their way to Bangkok, increasingly now they do, but in the years Sylvie was most active many did not. So, we are left with a relatively unknown reservoir of talent which does not register on the common Western fan's radar. So, what I did was take out all fighters in Sylvie's record who have not reached Western awareness (including only those that also would have, anachronistically). The list is of all fighters who have at one time, before or after Sylvie has fought them, been World Champions for International orgs (incl: WBC, WPMF, WMC, WMO, IFMA). These are fighters who at one point were regarded as the best in their weight class in the World. 39 times Sylvie has fought these one-time World Champions. Below records her opponents and her record against them. 18 fighters in all. Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu vs World Champions *adding to this Sylvie's 3 World Titles (WBC, IPCC 2x) The second difficulty in assessing Sylvie's record is that unless any female fighter (likely in history) she has fought well out of her weight class, sometimes 3 or 4 weight classes up. In her voracious drive to fight as much as possible she took fights that just no other officially managed fighter would take. Because she grew within the sub-culture and its language she was able to operate like a free-agent, booking her own fights. Because she was not represented by a powerful gym, or a powerful promotion, she could take fights that would be far outside the possibility of opportunity for others. This makes comparison with other female fighters extremely difficult, simply because nobody else has done this. There was a bold (and beautiful) challenge of Smilla Sundell for her belt by the excellent Allycia Rodrigues, fighting up a weight class (it may have been closer to two weight classes, as Smilla is large for her class, and Allycia seems modestly sized in hers). So much admiration for her to go for it. It's extremely rare for strong female fighters to fight opponents 2 or 3 weight classes up, even among Thais. Sylvie has done this regularly, not only against the talent pool of Thailand at large, but against World Champion skill-level opponents. In the graphic above there is also recorded a rough estimate of how many weight classes Sylvie was reaching up. Most often in Thailand (in part because Westerners are large-bodied, in part because Western friendly gyms have a lot of power in the fight-game), Western fighters are fighting down. Size advantages are quite common place in Thailand for the Western fighter. Sometimes its only a few pounds, sometimes its quite significant. This makes Sylvie size-charging even more difficult to assess. If she was managed in an official way most of the fights above would never been arranged. Gyms like to flex and get advantages for their fighters, and weight is one of the most common advantages pressed for. So, leave aside for a moment all of Sylvie's other fights, and just look at these 42 (including her own 3 World Titles). Notably, these are not champions derived from a single organization or promotion (sometimes champions can be produced out of very small fighter pools), these are champions recognized by different selection processes and politics, a cross-section of the sport. This is an unparalleled collection of challenge, and if she had only fought these fights, especially given the weight differences, it would likely count as the most difficult female Muay Thai record in history, fighting a whose who of a generation of female Muay Thai fighters within 3 weight classes. Again and again Sylvie took the very steep climb, getting into the ring against fighters, many of which she would not be favored again. 42 fights in generations past would be considered a decent career total for a Western female fighter. No, Sylvie did not fight each of these fighters when they were World Champions, that is not even concievably possible, they were not champions at the same time, and fighters ebb and flow in skill quality, but this remains a meaningful cross-section of female fighters, each of which have reached the peak of at least one org's measure of elite. Sylvie vs Internationally Ranked and Local Stadium Champions The additional list below shows the same fights individually, but also includes fighters who have been recognized by International organizations, ranked at some time by the WBC, WPMF, WMC or WMO. This list also includes local stadium champions, most of these drawn from Chiang Mai. Chiang Mai at the time when Sylvie did most of her fighting up there was a haven for female fighting because there was a female Thai stadium scene that was quite organized, and not for the Western tourist. Kob Cassette who ran the Muay Siam Northern Chapter, and the Thaphae stadium fight scene, specifically steered the scene away from Thai vs farang matchups, limiting such fights to only one on a card. Thais mostly fought Thais for the stadium belt, because they were working to build a Thai female Muay Thai legitimacy in the North. (In fact, Sylvie beat Faa Chiang Rai for the Northern 105 lb Muay Siam belt, but was stripped of it after she won it because it should only belong to a Thai). This is to say, these belts were seriously organized, primarily reflecting the best of the region among Thais. These were not the kinds of stadium belts that rotate among various fighters in tourism Muay Thai of other cities. The reason for including stadium champions though, aside from just respect for Thais in the Muay Thai of their own culture, is that these champions would in fact be ranked now, in today's leading procedures. The way that rankings of Thais work for orgs like the WBC is that knowledgeable Thai headhunters and promoters help inform the committee who is top in the country. This is extremely difficult and shifting knowledge in Thailand, and orgs that rank Thais in an updated fashion really need to be commended, but, this is to say, a Chiang Mai stadium champion of Sylvie's era in Chiang Mai would definitely be ranked by this process...now. So the list accurately captures a cross-section of fighter quality as it has been recognized by international orgs, or would be. These are all recognized fighters. There are some supremely good opponents in the rolls below, which could easily have been World Champion if given enough opportunity, fighters worthy of special mention like Gaewdaa (as sharp as any at 45 kg), Jomkwan (who in her prime when Sylvie fought her was as good as anyone she has faced), Muangsingjiew (Sawsing's cousin) so skilled, such a fighter, Thaksaporn (so tough). Adding up all lists these are, in total 149 fights. This total alone would be more documented fights than any Western fighter in Thailand, or more documented pro fights by a female Muay Thai fighter...in history. And all opponents recognized for their quality on an International standard. The entire collection of opponents, leaving aside the repeated weight disadvantages, is unheard of in female Muay Thai fighting. It's maybe 3 prolific female fighters records, combined in a single fighter, none of it of unknown fighters on a Western scale...and Sylvie has 125 more fights not on this list, made of fighters you might never have heard of, unless you were in those communities. But this doesn't mean that they also are unworthy. The interesting thing about Sylvie's record is that because she was not being booked by a powerful gym or being promoted by a promotion, almost all her fight matchups were created within the Muay Thai community, according to what seemed an equitable pairing. Nobody is punching down because nobody is exercising power on Sylvie's behalf. Each of these is a someone who has dedicated herself to her sport. This is the primary reason why Sylvie has fought up so often, and so much. It was regarded that notable weight disadvantages leveled the playing field. The community of Muay Thai regarded as these matchups as worth making, and Sylvie is almost always fighting up against these fighters. You never are going to get adequate one-for-one record comparisons within the sport of female Muay Thai. Female fighters follow different paths, and politics and opportunity combine to present distinct pools of fighters to face. And with the rise of Entertainment Muay Thai it is easy to think that the small pools of a single promotion's fighters may represent quality on the world scale (they might!), but fighter pools remain diverse and separated, generally speaking. Each prolific and great female fighter has told her own wonderful story in the pools she has been able to reach. Just because you may not have heard of a fighter doesn't mean that they lack quality. They might, but they also may be incredibly skilled...this happens all the time in Thailand, because the fighting is so widespread in the culture. Multiple times Sylvie, who has been about as aware of who the best female fighters in the world are as anyone, has been shocked by the skills of someone she faced who seemed to come out of nowhere. And, in Thailand, it is not completely uncommon to show up to a fight against an unknown fighter, only to find out that a World Champion (literally one of the best fighters in the world) has been subbed in, or is appearing under another name. No lights show, no fancy stadium, and you are facing one of the best in the world. Sylvie has fought so much, and so many opponents (now approaching 150 different Thai fighters), that she's learned that Entertainment shows, and org rankings are all drawing on the very same opponent pool that she is fighting. And often its Sylvie facing someone that puts them on the Entertainment radar. This is to say, let Sylvie's record be what it is...wonderful. A tremendous celebration of the female fighting of Thailand, especially of Thai female fighters...it is their sport, we are only privileged to be a part of it. As much as we Westerners would like to lay claim to achievement, what we have come to learn is that Thai female fighters are the best at muay of their country, the muay of their culture, the muay of their people. It's great to be exporting the sport, and building enthusiasm and passion for it around the world, but it all needs to start with respect for the Thai fighter, the fighter who knows it better than anyone else. You can find a spreadsheet of the above 149 fights of Sylvie's Record here. And the Complete Record of Sylvie's Fights is here (with links to video of - nearly - every single fight). We from the beginning have not only sought to be as transparent as possible about our experiences, we also have worked hard at documenting every single fight that we could, because the whole thing is a testament...not to Sylvie, but to all of Thailand's female Muay Thai. Sylvie video record captures the Muay Thai of more than a generation of female Muay Thai fighting in Thailand, including fighters of importance, passion and skill that may not yet or even been swept up in the Western media gaze, and so many who have been. It is an archive of female muay...that's why we record, that why we post and organize it all. You honor your opponents when you name them, and record their efforts in anyway, when you send their passion and commitment forward to the eyes of others. Also...and not less than this, Sylvie's commitment has been to the belief that the best way to love Muay Thai, and to know Muay Thai, is by fighting. She realized early on that generally belts meant very little compared to the actual experience of fighting itself. Fight everyone, fight often, that is the only way to come in contact, intimately, with the art and sport itself. Have those experiences. Each and every time you come out of a fight transformed, changed, grown. Take challenges, fight up! Each fight is precious, and this is the same feeling she has coming up on 300. If you think you are good at 50 fights, try 75, try 100, you'll be better, you'll know something more, something else. You'll love the art and sport more. The documentation of it all, is about that. This isn't to say that if you fight in other ways, under other standards of excellence, in different fighter pools, you are less great or wonderful. There are so many ways of fighting, of measuring, competing, becoming recognized, and fighters and their teams necessarily compare themselves. That's all good, its part of the passion. This is just to present this one wonderful example, hopefully to inspire this kind of fighting, if only a little bit.

-

Sylvie's Elitely Difficult Fight Record Just organizing Sylvie's record a little bit this morning, and noting this. It may very well be that no female Muay Thai fighter has fought a tougher collection of opponents than Sylvie has in the 39 fights. These are all her opponents who have been World Champion at one point in their career, and Sylvie's record against them. What is unparalleled, I believe, isn't the sheer number of World Champion quality of fighters, but also how many times she went up in weight to face them, including jumps of multiple weight classes. Weight is the single most determining factor of fight match up fairness, whereas Sylvie has consistently fought much higher than her weight even against elite level fighters. I can't think of a fighter who has done this.

-

How to Judge a Long Term Muay Thai Gym in Thailand A perspective of Muay Thai gyms in Thailand, from someone who has seen a few (usually with an eye towards: would this be a good place to train for Sylvie?) I've already written at length on the Authenticity of Muay Thai gyms, this is something else. This is something else. It's just a basic conception we've relied on in judging gyms. I see them something like production lines in a factory, maybe like a cupcake factory. This is not to say that the workings of a Muay Thai gym in Thailand are mechanistic, but rather that the dynamics of the gym may be occluded from view. You have all these gears and mechanisms, many of them you might not even understand or appreciate. Ways of training, reputation, social hierarchies & politics in the gym, the personality of the owner, fight promotion alliances, its a whole living thing in Thailand. But, what you want to look at...what I look at, is "what does it produce?" What cupcakes come down the conveyor belt? That's what the whole process is doing. Now, this is a little complicated in Thailand because in terms of Thais bigger name gyms actually buy their cupcakes already made. They buy them baked. They might put them through an additional process, develop them some, but mostly they were made elsewhere, by other processes. Their core skill sets, sense of timing, eyes, defensive prowess have already been "made". If its an Entertainment Muay Thai oriented gym they may now be training combos much more (added on top of their core skills), or hitting the gym for strength. If in trad shows the fighters may just be more tuning up and staying in shape and sharp. As someone coming long term to Thailand you probably, on the other hand, really want to get into the deeper processes themselves, which may not be where big name fighters are. There could be very good training around big name fighters, but it isn't likely developmental training, the thing that makes the cupcakes. For that you need to see Thai kids and teens. On another level though, many gyms have long term Westerners (and others). Pay less attention to the supposed training and trying to judge that from afar, and more paying attention to the way farang fight that have gone through that process over time. See what foreign cupcakes are coming down the conveyor belt. What do they fight like in the ring? What skills or styles do they show? Look for the kinds of cupcakes being made that you want to be like. Long-term farang usually settle into a training culture of their own in a gym, and may be even more important than the training prescription itself when it comes down to what the gym is going to make of you, because one is always taking cues from those to the left and right of you. It's one of the beautiful things about Thailand. Things like: how fast do you wrap your hands, how much do you chit-chat, do you do full rounds on the pads, do you do shadowboxing, or finish the run will be shaped by your co-fighters (students). I remember in our first year of Lanna 30 minute hand wrapping in the morning was kind of a thing, a thing Sylvie had to consciously fight against, because its was the gym tempo. Gyms might have reputations, good or bad, but look at what they actually make. That way you can align your desires to commitment. I want to undergo that. And...if the kinds of fighters coming out of a gym, made by that gym, both Thai and farang, aren't the kind of things you like, perhaps move away from that gym, because if you undergo those processes you too will look like that, those cupcakes. This isn't to criticize gyms, there are all kinds of cupcakes. This is actually one of our ways of thinking about gyms, for Sylvie (and sometimes others). To see the value of the forces that are at play, see what they do, and think: do I want some of that? Now for Sylvie who is intensely experienced (and pretty much fluent in Thai), and who has unusual requirements in Thailand (her size, her desire to be near Thai culture & training ethics, some freedom from Thai politics), things are a bit more complex. We think about this in layers. We look at gyms and see what cupcakes they make, and take from that a certain education about what the processes will do to you. Sometimes the cupcakes that are coming out of a gym might not be all that awesome, in terms of what you want to be, but you can still learn valuably from what is produced. Sometimes you can be: I want to train at this gym for this reason, or that (but I have to be careful because I don't want to be turned into that kind of fighter, the kind that this gym's processes tend to produce). With this you can ward off, or look for those things that make that kind of fighter, or...take precautions to look for these things in oneself. A great deal of training in a gym is unconscious. You become shaped by people training beside you, for better or worse. That's why the cupcake example is important. You don't necessarily have to identity what is producing quality x or y...you just have to be aware that this is what tends to happen. Sometimes its as simple as: This gym produces lazy fighters, this gym produces very tough fighters. Even broadbrush things like this come out of the culture of a gym and its practices. The way that authority and values are exercised, the aesthetics of its muay. This alone might be a reason to train at a gym, or avoid one. The vibe is contagious, and shaping, even if you are experienced. For Sylvie she build-a-bear's her training, from different gyms, and private training, because its hard to find a gym that has "everything" so to speak. You look at certain things different gyms do well, and try to weave them. This though, is incredibly difficult in Thailand politically, and isn't advised. I mention it only to expand on the cupcake factory idea, that gyms can tend to produce qualities, qualities that draw your eye. To return to more regular examples, if you are drawn to technical training don't just think about whether there is correction in training. Look at how long term farang fighters fight, coming out of that gym. If you are looking for Muay Khao training, do the long term farang from that gym fight as strong Muay Khao and clinch fighters? Look at Instagram and Facebook pages and watch some fights, if you are researching seriously. Off the top of my head if you want an example from female fighting I'd take a look at Alycia and Barbara at Phuket Fight Club, something I've thought about. I haven't a clue what their training is like, and I really don't care that they are on big name promotions. If you look at the two fighters you can see what they train. They are both intensely driven, have sound principles, fight within themselves (what they know they do well), have a core, effective forward style, are tough minded with a technical dimension and are open to clinch. There are many important things that could probably be said in much more detail by people in the ground, but you can see what the gym has made, its processes. Jalill Barnes who also trains there, much of the same qualities. I'm not even recommending the gym (I don't know much about it), I'm just using the example to show how you can see the process in fighters. I don't mean to single it out, but I needed an example to keep the whole thing from being too abstract. It's not that everyone fights the same, or even that a gym has a style (some might). It's that certain qualities get disseminated through the process of training, and a gym's support or allowance of those qualities. Sometimes this is expressed in style, sometimes in other things. But, largely when positive qualities show themselves, things you are looking for, this is a good thing. It means that there is a consistent way.

-

Fighting Big It's crazy, just looking at Smilla's record, a very fine fighter and possibly this gen's best fighter (?). Of the 17 documented fights, Sylvie has fought TWO of Smilla's opponents (Pornpan & Nongbiew, 1-1), and also 2 high profile opponents of her opponents (Dongkongfah - who beat Alycia Rodrigues for the Thailand belt & Hongthong who beat Diandra Martin on RWS). Smilla is a 125 lb fighter, Sylvie a 100 lb fighter. One of these was a ways a back, so Smilla, who I love as a fighter, wasn't as big probably....but it goes to show that Sylvie has fought pretty much more than a full generation of Thai female fighters, across all weight classes. And Sylvie is 4-3 against them.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.