-

Posts

2,264 -

Joined

-

Days Won

500

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

Yesterday I was quite surprised to hear Chatchai Sasakul telling us that people problematically slowdown their punches, and lack the natural acceleration that is necessary at the end. The "shape" of their punches is all wrong. I was surprised because this validated what I wrote 2 years ago, exactly that. I got a lot of flack from internet authority types.

-

Regional Golden Age Muay Thai - Khon Kaen Hanging with Karuhat I asked him: Are there any more good fighters from Khon Kaen (where he is from and famous for very femeu fighters like Pudpadnoi, Himself, Somrak, etc)? He shook his head. No, there was a very big stadium there, like Lumpinee. They had a big card every Saturday, broadcast on channel 4 - which I take to be a local broadcast. The stadium was the focus of the region's entire scene of Muay Thai. The stadium closed maybe 20 years ago. He said he fought in the stadium maybe 4 times.

-

That looks like a good list. A very toured gym for clinch is FA Group in Bangkok, but you might just be clinching a lot with Westerners? There is a very heavy Western presence, lots of Westerners trying to learn clinch. Kru Diesel is the kru who made FA Group (before it became a destination gym), so if you are looking for the deeper theory of the clinch fighting style kru Diesel is the source. Kem is very good teaching clinch, maybe take a few privates with him for that focus? A lot of clinch is like surfing, you need to spend time in the waves...but (who are you clinching with) the waves also matter.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

The Living Real. Goddess of warfare and wisdom. The goddess Pallas Athena was a divinity of both warfare and wisdom. Sylvie in her 285th fight, embodying both in the material world. The Greeks held ideas to float above us as inconcrete things...toward which we strive. I am inspired by my wife, as I would be by the ideas of Athena. She walks where no one else has and invites us to see. We learn from ideals. We learn from their examples. We learn as we all strive. I see this bloody photo in the corner between rounds, and I see the ideals of Athena, pressed through the mess of the human, the contorting real of bodies and wills clashing, in their techniques and arts (for we are all made of habits). Every Muay Thai fight opens with the embodiment of gods and divinities in the Ram Muay, some might say, quite literally. When fighters enter the ring they take on a role that is beyond the merely human. Athena always has been an anathema. She dictates the priorities of justice, rationality and even democracy, yet she wears the cult-like aegis which puts pure terror into enemies on the battle field. She was reportedly born virgin, from her father's thigh, is a maiden but stays the hand of Achilles with the scales of wisdom.

-

Deleuze, Guattari and the Machinic The "combo" or even "the strike", as it lives in the Western conception, would benefit from understanding the machine from a D&G perspective...from the excellent chapter "What is the Body Without Organs? Machine and Organism in Deleuze and Guattari" by Dan Smith. found here: What is the body without organs_ Machine and organism in Deleuze and Guattari.pdf << pdf

-

The West vs Thailand The more I think about it - and I've thought about it a lot - the huge difference between most combat sport conceptions in the West vs Thailand's Muay Thai is The Burst vs The Continuity. Short Wave vs Long Wave...with the exception perhaps of Western Boxing, which has a tremendous history of long wave fighting. With the advent of the "combo" (which helps people who are not fluent, teach and disseminate) and of the "highlight" (which increasingly becomes the narrative lens through which fighting is digested and understood), The Burst concept has accelerated...to everyone's detriment.

-

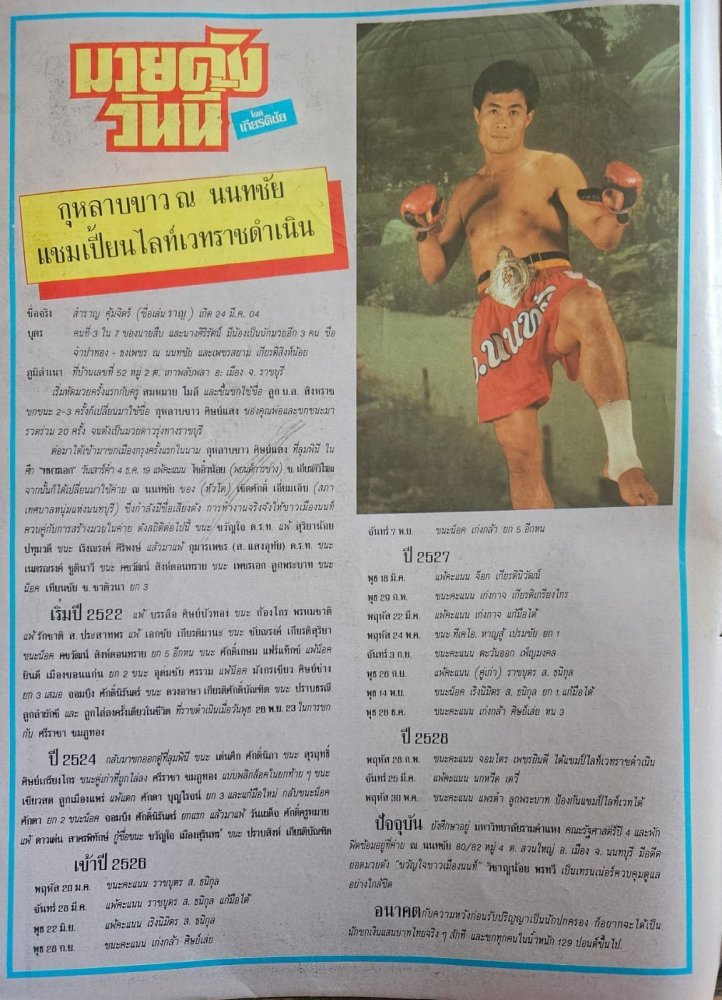

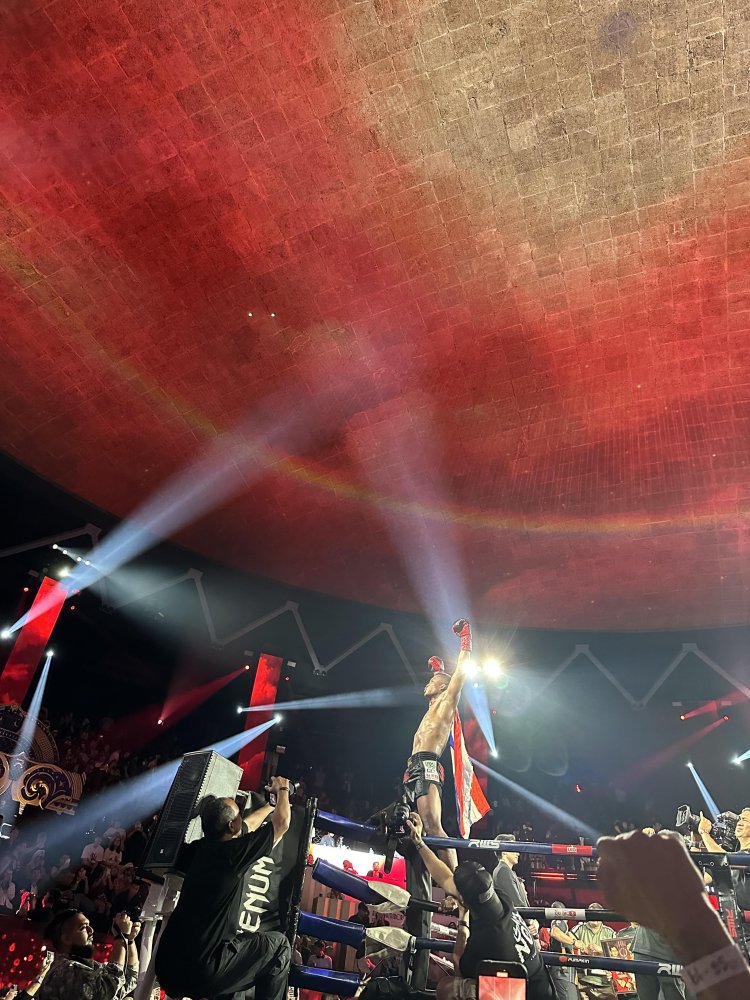

I was legit sad to see Rajadamnern do away with the lighting they had, with the checkerboard, because it allowed me to take some of my best photos ever. I just loved this photoshoot. It gave such a sculptural light. But, this informal shot (sorry I don't know who took it) from the new lighting shows that there can be some very dramatic photography in the stadium. I hope I get to shoot there again with the new lighting. Props to whomever made the bold move, from something that was already a strength of the stadium, pushing for something that might be better.

-

The Chicken Wing Punch in Thailand my answer below to this Reddit question, which the moderators for some reason deleted. Who knows why, maybe some kind of AI filter, etc? This is a very interesting subject though, reflecting on the way techniques get preserved and passed on. Do people who do muay thai punch oddly? The author then went onto describe how they've been told by some that they punch like they are throwing an elbow, but that this is how their coach taught them. I assume you are talking about straights and crosses. In most examples, in Thailand this chicken wing punch honestly is likely just a collective bad habit developed out of bad padholding, often with wider and wider held pads (speculatively, sometimes because Thais hold for very large Westerners and don't want to take the full brunt of power all day long). It also has proliferated because Thailand's Muay Thai has moved further and further away from Western Boxing's influence, which once was quite pronounced (1960s-1990s, but reaching back to the 1920s). Today's Thai fighters really have lost well-formed punching in many cases. It has been put out there that this is the "Thai punch" (sometimes attributing it to some old Boran punching styles, or sometimes theoretically to how kicks have to be checked, etc), but Thais didn't really punch like this much 30 years ago if you watch fights from that time. It's now actually being taught in Thailand though, because patterns proliferate. People learn it from their padmen and krus (I've even heard of Thai krus correcting Westerners towards this), and it gets passed on down the coaching tree. Mostly this is just poorly formed striking that's both inaccurate and lacking in power, and has been spreading across Thailand the last couple of decades. There are Boran-ish punching styles that have the elbow up, but mostly, at least as I suspect, that's not what's happening. We've filmed with maybe (?) 100 legends and top krus of the sport and none of them punch with the "chicken wing" or teach it, as far as I can recall.

-

The BwO and the Muay Thai Fighter As Westerners and others seek to trace out the "system" of Muay Thai, bio-mechanically copying movements or techniques, organizing it for transmission and export, being taught by those further and further from the culture that generated it, what is missed are the ways in which the Thai Muay Thai fighter becomes like an egg, a philosophical egg, harboring a potential that cannot be traced. At least, one could pose this notion as an extreme aspect of the Thai fighting arts as they stand juxtaposed to their various systemizations and borrowings. D&G's Body Without Organs concept speculatively helps open this interpretation. Just leaving this here for further study and perhaps comment. from: https://weaponizedjoy.blogspot.com/2023/01/deleuzes-body-without-organs-gentle.html Artaud is usually cited as the source of this idea - and he is, mostly (more on that in the appendix) - but, to my mind, the more interesting (and clarifying) reference is to Raymond Ruyer, from whom Deleuze and Guattari borrow the thematics of the egg. Consider the following passage by Ruyer, speaking on embryogenesis, and certain experiments carried out on embryos: "In contrast to the irreversibly differentiated organs of the adult... In the egg or the embryo, which is at first totally equipotential ... the determination [development of the embryo -WJ] distributes this equipotentiality into more limited territories, which develop from then on with relative autonomy ... [In embryogenesis], the gradients of the chemical substance provide the general pattern [of development]. Depending on the local level of concentration [of chemicals], the genes that are triggered at different thresholds engender this or that organ. When the experimenter cuts a T. gastrula in half along the sagittal plane, the gradient regulates itself at first like electricity in a capacitor. Then the affected genes generate, according to new thresholds, other organs than those they would have produced, with a similar overall form but different dimensions" (Neofinalism, p.57,64). The language of 'gradients' and 'thresholds' (which characterize the BwO for D&G) is taken more or less word for word from Ruyer here. D&G's 'spin' on the issue, however, is to, in a certain way, ontologize and 'ethicize' this notion. In their hands, equipotentiality becomes a practice, one which is not always conscious, and which is always in some way being undergone whether we recognize it or not: "[The BwO] is not at all a notion or a concept but a practice, a set of practices. You never reach the Body without Organs, you can't reach it, you are forever attaining it, it is a limit" (ATP150). You can think of it as a practice of 'equipotentializing', of (an ongoing) reclaiming of the body from any fixed or settled form of organization: "The BwO is opposed not to the organs but to that organization of the organs called the organism" (ATP158). Importantly, by transforming the BwO into a practice, D&G also transform the temporality of the BwO. Although the image of the egg is clarifying, it can also be misleading insofar as an egg is usually thought of as preceding a fully articulated body. Thus, one imagines an egg as something 'undifferentiated', which then progressively (over time) differentiates itself into organs. However, for D&G, this is not the right way to approach the BwO. Instead, the BwO are, as they say, "perfectly contemporary, you always carry it with you as your own milieu of experimentation" (ATP164). The BwO is not something that 'precedes' differentiation, but operates alongside it: a potential (or equipotential ethics) that is always available for the making: "It [the BwO] is not the child "before" the adult, or the mother "before" the child: it is the strict contemporaneousness of the adult, of the adult and the child". Hence finally why they insist that the BwO is not something 'undifferentiated', but rather, that in which "things and organs are distinguished solely by gradients, migrations, zones of proximity." (ATP164)

-

The Labor Shortage in Muay Thai As the Thai government is pushing to centralize Muay Thai as a Soft Power feature of tourism, and as Thai kaimuay become rarer and rarer, pushed out by big gyms (scooping up talent, and social demographic changes), there is a labor shortage for all the fights everyone wants to put on. There are two big sources to try and tap. There are all the tourists who can come and fight on Tourism Muay Thai (Entertainment) shows, and there are the provinces. The farang labor issue is taken care of by rule changes and Soft Power investment, but how do the provinces get squeezed in? Well, ONE Lumpinee is headed to the provinces, trying to build that labor stream into its economic model, and cut off the traditional paths from provincial fighting to Bangkok trad stadium fighting, and top BKK trad promoters are focusing more on provincial cards. There is a battle over who can stock their fight cards. ONE needs Thais to come and learn their hyper-aggressive swing hard and get knocked out sport, mostly to lose to non-Thais to grow the sport's name that way, fighting the tourists and adventure tourists, and the trad promoters need to keep the talent growing along traditional cultural lines. As long as the government does not invest in the actual ecosystem of provincial Muay Thai (which doesn't involve doing money handouts, that does not help the ecosystem), the labor stream of fighters will continue to shrink. Which means there is going to be a Rajadamnern vs Lumpinee battle over that diminishing resource. The logical step is for the government to step in and nurture the provincial ecosystem in a wholistic way, increasing the conditions of the seeding, small kaimuay that were once the great fountain for the larger regional scenes and kaimuay. headsup credit to Egokind on Twitter for the graphics. "You can get rich!!!!!!" (paraphrase)

-

The Three Great Maledictions on Desire I've studied Deleuze and Guattari for many years now, but this lecture on the Body Without Organs is really one of the the most clarifying, especially because he leaves the terminology behind, or rather shifts playfully and experimentally between terms, letting the light shine through. This is related to the continuity within High level traditional Muay Thai, and the avoidance of the culminating knock-out moment, the skating through, the ease and persistence. (You would need a background in Philosophy, and probably this particular Continental thought to get something more out of this.) And we saw on previous occasions that the three great betrayals, the three maledictions on desire are: to relate desire to lack; to relate desire to pleasure, or to the orgasm – see [Wilhelm] Reich, fatal error; or to relate desire to enjoyment [jouissance]. The three theses are connected. To put lack into desire is to completely misrecognize the process. Once you have put lack into desire, you will only be able to measure the apparent fulfilments of desire with pleasure. Therefore, the reference to pleasure follows directly from desire-lack; and you can only relate it to a transcendence which is that of impossible enjoyment referring to castration and the split subject. That is to say that these three propositions form the same soiling of desire, the same way of cursing desire. On the other hand, desire and the body without organs at the limit are the same thing, for the simple reason that the body without organs is the plane of consistency, the field of immanence of desire taken as process. This plane of consistency is beaten back down, prevented from functioning by the strata. Hence terminologically, I oppose – but once again if you can find better words, I’m not attached to these –, I oppose plane of consistency and the strata which precisely prevent desire from discovering its plane of consistency, and which will proceed to orient desire around lack, pleasure, and enjoyment, that is to say, they will form the repressive mystification of desire. So, if I continue to spread everything out on the same plane, I say let’s look for examples where desire does indeed appear as a process unfolding itself on the body without organs taken as field of immanence or of consistency of desire. And here we could place the ancient Chinese warrior; and again, it is we Westerners who interpret the sexual practices of the ancient Chinese and Taoist Chinese, in any case, as a delay of enjoyment. You have to be a filthy European to understand Taoist techniques like that. It is, on the contrary, the extraction of desire from its pseudo-finality of pleasure in order to discover the immanence proper to desire in its belonging to a field of consistency. It is not at all to delay enjoyment. This is not unrelated to the Cowardice of the Knockout piece I wrote:

-

Wow, Dangkongfah "moo deng" (as they call her) won again. It fits a beautiful way. Always enjoy watching her fight. Such an interesting fighter, we know her so well. Her opponent fought valiantly, trying to solve Dangkongfah's frustratingly minimalist style, but it wasn't enough. Dangkongfah won an important, decisive exchange in the 4th that locked up the narrative win, and then coasted to close femeu in the 5th, what she's so good at, retreating and nullifying. It's very nice to see Patong stadium reffing and judging in the traditional style, holding the line against Entertainment Muay Thai. A very well reffed fight. The promotion looks so solid, right in the middle of Phuket's Muay Thai scene. Very cool. This was a great test-case fight for those kinds of differences. Two fights in a row (at least) down in Pkuket, I wonder if Dangkongfah has moved down there to live and train. If so, she'll have a substantive trad promotion to fight on regularly.

-

What farang authoritative convo was like in 2006-7, training Muay Thai in Thailand, interesting to read through. As a sidenote, apparently Fairtex has been "reconditioning" older Thai fighters with "modern" training (including being trained by an "ex Mr. Universe, being given "scientific nutrition such as post workout protien/carb drink etc"), moving some of them up weight classes so they can fight Westerners for over two decades at least. The Entertainment recipe has had legs there. some of the back and forth, the whole thing interesting. the link is here, I got a minor virus warning on it when I posted it so click over on your own caution. It wasn't a problem for me: www.defend.net/deluxeforums/forum/martial-arts/thaiboxing-and-kickboxing/21237-training-camps

-

In some sense this is like asking MCU or DC Universe films, and thinking Marvel is good "cinema" just because it's not DC. RWS is better, in fact much better, but its still the same kind of thing, both of them trying to cast as many "traditional" fighters (actors) as possible, to give that authentic cinema feel.

-

The Chinese Middle Man to Provincial Siam, and the Muay Thai of the Provinces from A History of the Thai-Chinese One of the most interesting (mostly hidden from Westerners) aspects of Thailand's Muay Thai is the headhunter for Muay Thai talent in the provinces. Many Sino-Thai Bangkok promoters and big gym owners constantly have their feelers out in the provinces, seeking fighters for the Bangkok Stadia. This pattern exists today, even for female fighters. The attached pages tell the story of how the Rice Boom in Siam, wherein it became the rice-basket for the labor markets of Southeast Asia and beyond, helped create this pattern of isolated provincial production and the Sino-Thai middleman manager who traveled the country, collecting product. In the case of rice, to be transported and milled in the Capital. If you read the pages you'll find the same insularity of village culture whose imprint you can still experience today, and the liberty with which the cosmopolitan Sino-Thai businessman flowed across Siam, creating a symbiotic relationship, which actually helped preserve village life and culture (for better or worse, depending on your politics). In Thailand today there still is a firm, almost world barrier between major city centers and the countryside, the capital and the provinces, with cosmopolitan agents cross-crossing the territories.

-

This was just an incredible slice of Muay Thai that Sylvie and I experienced, just talking to her about it now. For an entire year Sylvie training like this ending up at night at Jeejaa's gym, mostly just her and her brother and father, training with an absolute unicorn of a female fighter when she was arguably the p4p best female fighter in the world, at the age of 12-14, traveling around to fights with her in the provinces. This is a reality nobody else could have experienced, as she wasn't part of a gym with other fighters, she was made through her family, and a side-bet fighter. I think at this age she probably was the best Thai female Muay Thai fighter who has ever fought, though Loma has a case. Some of what we filmed of Phetjee Jaa fighting then:

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.