-

Posts

2,264 -

Joined

-

Days Won

500

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

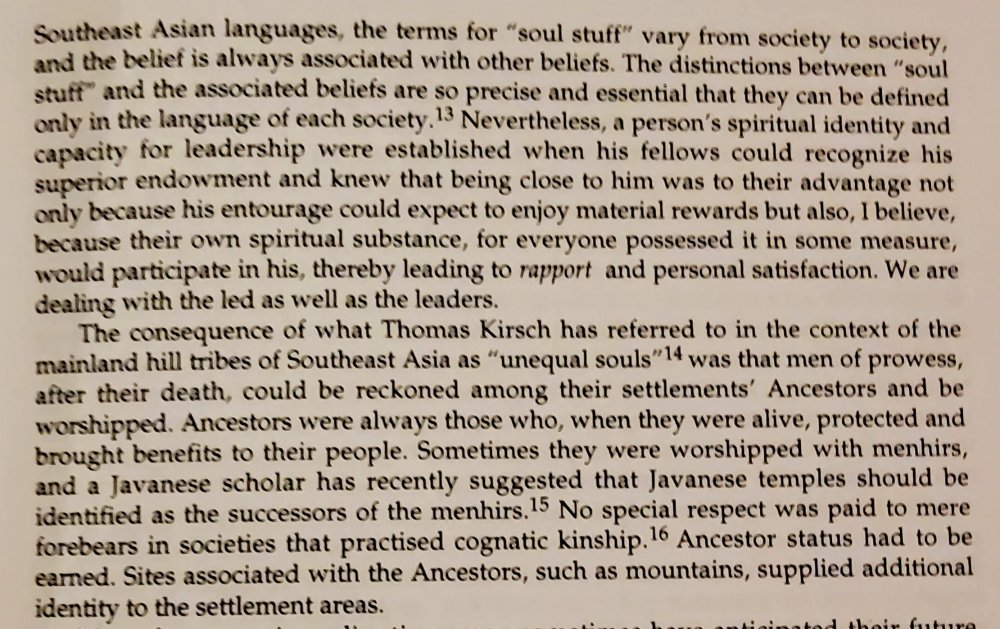

A question that sometimes is raised is: What is the religion of Muay Thai? Or probably better put: Is there religious meaning in Muay Thai? Sometimes behind this question are the pictures of spirituality within traditional martial arts like Kung Fu or Karate, an idea of self-perfection which is grounded in a deeper spiritual belief. The martial artist is perfecting themselves both physically and spiritually at the highest levels. Many answer this question in the negative, in a way that seems quite accurate at first. "There is no spiritual meaning to Thailand's Muay Thai." It is a fighting art, a sport, its meaning is in its efficacy. Looking for religious or spiritual beliefs in it would be like looking for them in Western Boxing. Yes, there are important cultural rites & practices which derive from Buddhism and the older form of Brahminism, and even the animism before that, but one does not have to be a Buddhist, let's say, to practice Muay Thai - and often these rites & practices are treated as cultural trappings by observers, a kind of respect paid to the past that could easily be shed without missing a beat. They aren't necessarily active religious practices, some say, while for others within the sport & art they treat these as highly meaningful, without which Muay Thai would lose its footing. If one had to give a single religion to Muay Thai it would be its Buddhism, in the sense that it grew out of a culture of Buddhism for the last 800 years, and in many respects has the qualities that it has because of Siam & then Thailand's Buddhism. It's traditional treatment of aggression, the way in which its scoring and overall style of fighting is classically handled with emphasis on ruup (posture), balance & self control, its treatment of the affects of anger and fear are quite Buddhistic. And notably within the culture there have been cultural parallels between between novice monkhood and the path of the young nak muay. You can read about some of those here: Thai Masculinity: Postioning Nak Muay Between Monkhood and Nak Leng – Peter Vail. When we see Thailand's Muay Thai through the lens of Buddhism not only do certain aspects of its scoring and presentation make more sense to foreign eyes, also questions as to how could such a violent sport be religious at all finds some resolution. There is an undeniable fabric to Thailand's Muay Thai which seems quite Buddhist, as it has been the dominant religion in the region within which it grew. And this is not to minimize that Muay Thai was also fed, perhaps for centuries, by the very high level Muay Thai of the South which has a significant Muslim population. Muay Thai is actually much more of a tapestry than many assume. There are threads in the fabric. We are left somehow with an unsatisfying answer. Yes, Thailand's Muay Thai expresses and comes out of a (largely) Buddhistic culture and holds several rites and practices which are religious in nature - the treatment of the mongkol, the pre-fight Wai Kru/Ram Muay are the most obvious ones - and even we might grant that in the cultural maturation of boys the kaimuay (boxing camp) has stood as an alternative to the maturation in the wat (temple). Or, we might even imaginatively acknowledge that in its history temples were likely houses that kept Muay Thai and transmitted its form, for centuries (perhaps even in some modest Shaolin, temple-kept, non-government sense), a magic-imbued Muay Thai that is likely lost to today (practices outlawed in 1902). But still, what is its religion? Are Muay Thai fighters doing anything religious that is intimately connected to their performance? Is the arduous and obedient training in Muay Thai in any sense a spiritual practice? I believe they are, and there is. "Soul Stuff" and Muay Thai Anthropologists and historians who have studied the history of Siam (Thailand), and Southeast Asian culture in general, have wrestled with thinking about the fundamental nature of its social organization, as it is has appeared throughout the centuries. Mainland Southeast Asia from about the 1st century AD went from small settlements and polities to eventual powerful trade centers and then empires, a transformation likely fueled by a connection to India. The great temples of the Khmer, the religious cults to Shiva, the establishment of potent royal figures has largely been credited to what is called "Indianization". The culture of India pervaded Southeast Asia in a manner some compare to how Roman culture passed over Europe. The presence of statues to Ganesh, the identification of Thai royalty with Vishnu, even the invocation of the Ramayana in the Muay Thai Ram Muay are all expression of this period of "Indianization" begun nearly 1,700 years ago. This is a very long lineage. Atop this layer of pronounced Hindu/Brahminist influence sits Buddhism itself, which transformed the politically Indianized culture further. It's important to realize that these two very strong influences are not (fundamentally) in conflict. The spiritualities expressed in Hindu form, especially in political contexts, were even furthered in Buddhist devotion. The forms of its expression are different, but the fundamentals of power and spirituality remained the same. And this is important to understand. Power and spirituality are bound together. We can see that even at a basic level questions about identifiable religion likely have braided answers. For historians the answer to why Hinduism, and then Buddhism, were able to powerfully graft onto Southeast Asian culture lies within the supposition of an older belief, something that lies below these historical sedimentations - why the receipt of salvation religions which gave voice and form to this older belief. It is this older belief (some have called it a "cultural matrix") which in a sense glues together the practices, and informs sociability itself, even the secular sociability of today. And this is the belief of "soul stuff". This belief interpretation was first put forward by the preeminent historian of Southeast Asia O. W. Wolters (link at the bottom of this post), but for our purposes this summation of it by Michael Charney in his book Southeast Asian Warfare: 1300-1900 (2004) is a very good entry point Everything in the world has a certain amount of stuff. A potency. And they do not have it in equal portions. Rocks have it, but a particular rock might have a great deal of it. Humans have it, but particular humans may have much more of it than others. Importantly, this is something you can acquire. You can have more soul stuff than you were born with, and it is something that can be transmitted between persons & objects. This can happen through association, physical touch, and a host of magical-religious practices. You can read into Wolter's original discussion of soul stuff here. Because he is investigating the origins of the Indianization of mainland Southeast Asia he is looking at the role of kings, and rulers of polities. For him it was the de-emphasis on lineage, the generational demand for personal performance, proving and acquiring "soul stuff", which kept Southeast Asia from adopting some of the more rigid social forms of Indian culture. Instead, because of the very nature of soul stuff in Southeast Asia political power had a fundamental agonistic quality to it, generation to generation, locality to locality, and (very importantly for our purposes), martial power and spiritual power were expressive of a single thing...soul stuff. He accounts how early kings were defined by their "prowess" and this prowess was expressed into only in terms of martial force, but through religious, aesthetic devotion. Within this under-fabric of Southeast Asian culture was a strong, bonded identity between physical prowess and spiritual prowess...and, the braiding of these two was expressed through "charisma". As Wolters writes: In the beliefs, the under-beliefs of Siam, the "priest" and the "warrior" were not separate. They were brought together in single personage, and this personage could be recognized by their charisma, their aura, which drew people to them. I think its important to realize that this isn't just a description of the rulers of polities. It actually describes how power ("soul stuff") is distributed throughout the entire lived world. Kings are said by historians to have mandala power, which is to say a certain sphere of influence which flowed out like candle-light in a circle. The further away from the center of this mandala power, the less it exerted itself. But lessor nobles, lessor polities also had spheres of power, a function of their charisma. In fact arguably, everything with soul stuff had circles of charismatic power. Some with very little, some with much more. The religious development of Siam can be thought of as expressing this much deeper, older sensibility toward the world and others, something that still persists (quite strongly) even today. It, in a sense, may animate present day Hinduistic and Buddhist beliefs with a particular logic of personal potency. Conquerous kings were also ascetic spiritual achievers who used the charisma of their personal achievement - the sign of their "soul stuff" - to glue kingdoms together. Here Wolters outlines how the much more ancient belief of soul stuff expressed itself in Buddhism through the personal spiritual achievement of Kings. The transmittability of soul stuff found firm expression in the Buddhist principle of merit (edit in: in later posts to this thread hpon, punna and merit are shown in the Thai concept of barami). I'm now going to race ahead to the subject of Muay Thai and religiosity, in this context, and work backwards from there. When one is training in Muay Thai in Thailand one is training in soul stuff. If you are not from the culture you might not realize or recognized why you are being trained a certain way, or even what qualities are being instilled in you, but if you undergo the process you are training in the acquisition and signification of soul stuff. And this is to some degree a spiritual ascetic practice, even if you approach it from a completely secularized place, and even if your trainers are not consciously expressing religious beliefs. This is the older form of the marriage of the martial and the spiritual, as it has been inherited, and to some degree sublimated, by the culture. And Thais who train in Muay Thai, who are part of the culture, are training in "soul stuff". The art of Muay Thai is developing the "prowess" which will eventually be expressed as a charisma (as it is culturally defined). One of the most subtly cutting criticisms of contemporary Muay Thai that we've heard was in a casual conversation between the legend Karuhat Sor. Supawan and WBC World Boxing Champion Chatchai Sasakul, both prolific fighters in Thailand Muay Thai's Golden Age. "Fighters no longer have charisma (sanae) today" they mourned. This wasn't a complaint about marketing, it was about the nature of the fighting itself. Fighting does not express the charisma that it once did. The reason why this criticism silently cut so deep is that the development of charisma was actually the point of Muay Thai fighting itself. Charisma is the aura one has, the capacity somehow (magically) draw people to you. It is a certain kind of personal gravity, which directly exudes your "soul stuff". It is your ittiphon, your power to influence. And it can be shown or lies in parallel to your ittirüt, which is your invulnerability. The connection between charisma and invulnerability is what lies beneath classic Muay Thai forms. The emphasis on ruup (posture, visible form), balance, freedom, control, and the fighterly aim of not necessarily "damaging" your opponent, as so much as dominating your opponent in a great variety of ways, including physical damage, is about the cultivation of charisma. This literally is the same kind of charisma of ancient kings, within the same scope of connective beliefs, trained for performance in the ring. Because Thailand is predominantly a Buddhist culture - and has been for much more than 1,000 years, the cultural form of that charisma has Buddhistic expression. In the same way that Buddhist novice monks seek to discipline their bodies, temper the hotter emotions, cultivate a kind of stoicism under travail, the young nak muay seeks to do the same. And great monks, through their ascetic practices, acquire great charisma revealing their "soul stuff". In some sense Thailand's Muay Thai has split off from many of the religious forms of charismatic development, but still expresses the same spiritual reality, even if in practice if falls into a broken, or and much less unreadable state. The ascetic practice, and the hierarchies of respect and rite in the gym are cultural pathways of "soul stuff" development. And arguably, anything you are learning in a Thai gym, whether it's the ability to endless do knees on the bag, or how to stay calm under sparring pressure, or how to properly block, or how to compose yourself under the exhaustion of padwork, are all actually about charisma, a projected invulnerability and magnetic aura, each fighter of which would have their own version. As Wolters emphasized, it is both a physical prowess and a spiritual prowess. Soul Stuff and the Magical Policeman The role of magical beliefs in the history of Muay Thai development is likely quite pronounced. If you would like to read an account which exemplifies the parallels between combat prowess and magical capacities, read the biography of the southern Thai policeman, Khun Phantharakratchadet (1898–2006) whose prowess occurred in the decades of Muay Thai modernization, and Thailand's rise as a modern Nation. It is important to understand that the development of fighting techniques (the knowledge of them, wicha) were historically not divorced from the development of magical techniques (that protected or aided you). Wats, traditionally, were likely a home for both. The tale of Khun Phan, a legendary real figure of Thai early modern 20th century history, recounts his advance as a physically small man who was a fierce fighter, taking on the nakleng gangs of the Sangkla area, and eventually other regions of Thailand, armed with his knowledge of the fighting arts, as well as study of the magical arts at the foot of the famed monks of Wat Khao Aor Or. in Phattalung. He even became proficient in Western Boxing (& perhaps Judo) studying at a wat in Bangkok, as part of his advancement as a policemen. He was a man of a remarkable amount of "soul stuff", much of it acquired through rigorous study and practice. The magical arts of Amulet protection, and sak yant are expressive of this spiritual under-logic of soul stuff. Everything has soul stuff, but pieces of material can be imbued with soul stuff, and because soul stuff is transmittable, it can be conferred to you through proximity or practice. Holy men, through rite and ritual can transfer soul stuff to you, and through spiritual practice you can hold it. Sak yant (sacred tattooing) are often devices of "soul stuff" transmission. They are thought to express/transfer the soul stuff of animals (tigers for instance) or gods, or heroic figures. They are thought to bring powerful energies, and often sak yant specifically bestow powers of charm or charisma (the ability to influence), or the power to command (amnat). In some cases creating invulnerability. Today, in their more commercial form they may be more thought of as one-way transmissions, but originally they involved spiritual devotion and self-transformation through practice. You achieved their powers through a growth in personal "prowess". It's enough to say that in the body of magical beliefs in Thailand we can see the nexus between martial prowess, spiritual power and charisma. These beliefs and practices, based in the logic of soul stuff, developed in parallel to the fighting arts of Thailand. Khun Phan at the age of 90 commissioned a Jatukam Rammathep amulet, believing that the spirit of Jatukam Rammathep had helped him solve a difficult murder case. The creation of this amulet by such an auspicious person, under the blessings of the Holy Pillar of Nakhon Si Thammarat, thought to be invoking spirits of great personage and Buddhistic merit created incredible demand. The substance of the Holy Pillar, the legendary policeman Khun Phan, and the proposed spirits Jatukam Rammathep, were put into physical objects, which then could transmit soul stuff to you. This is a logic of soul stuff. My brief detour into the magical arts is not to ascribe them or their complex beliefs to the spirituality of Muay Thai in particular. One is not to exclude them either, as still there are amulet practices of blessing and transmitted soul stuff, including those of the mongkol and prajet, or the invocation of dieties in the Ram Muay to begin every fight. More important is not to locate any set of beliefs and practices as necessarily religious, but rather to look at these beliefs and practices to understand how the logic of soul stuff transmittability expresses itself in Thai culture...and in Muay Thai itself. Magic is part of its heritage, but that heritage is founded on much deeper, metaphysical ideas on how power works in the world, and between humans. And this belief, I would suggest, is embedded to this day in even the most secular-seeming aspects of Thai life. There is a Buddhist perspective which may say that because of karma and reincarnation everything we do is spiritual practice. Everything we do is an attempt to alleviate or ease the suffering of existence. In this spiritualization of the world and culture, the belief in the transmittability of "soul stuff", of unequal souls, also can be seen as universal and pervading every practice. Much as a Western philosopher like Foucault may see all our interactions transpierced with discourses of power, all sociability in Thai culture can be seen as practices of soul stuff. It's development, its preservation, its signification, and the ways in which everyone takes position in society in relationship to powerful personages (whether they be local persons of aura, or National) who exhibit soul stuff. It is a kind of religion of existence. Soul Stuff and Muay Thai We can leave aside magical practices for now, and think about how soul stuff and Muay Thai relate. The first and obvious way is that because Muay Thai is a public performance the job of the fighter is to express "soul stuff". That means knowing the cultural signatures of "soul stuff", being practiced in displaying them, including aspects of command and control, invulnerability and of course charisma. Perhaps no fighter in history displayed soul stuff more than Samart, who expressed a very Rama/Vishnu quality, a potent equipoise. You cannot thoroughly understand Samart's greatness without seeing just how much (read here:) he signified "soul stuff" within the culture. This photo of him with the vanquished and bloody (aggressive, Muay Khao great) Namphon, gives some sense of it. But the signatures of soul stuff in Thailand's Muay Thai, and even kinds of personal charisma are not only of one kind. A great, unrelenting knee fighter like Dieselnoi will have tremendous soul stuff. A great pressure fighter like Samson, or a complex style fighter like Chamuakpet (naming legends of the Golden Age). There are various expressions of soul stuff. And, unlike in Western conceptions of "great fighters", soul stuff includes many things beyond the fighter. Samart for instance did not fight up very much in his career. In a Western mind this may be something of a demerit when compared to other great fighters who did. But because soul stuff is transmittable, and governed by association, the fact that Sityodtong gym was so powerful to be able to dictate favorable matchups (or at least avoid unfavorable ones) actually goes to Samart's soul stuff. He is part of a local nexus of power. Sityodtong has soul stuff. Master Tui has lots of soul stuff. Samart has soul stuff. As much as we want to think about fights as being between two isolated fighters in the ring, the truth is that there is much more in the ring than that. All the soul stuff that brought these fighters into being, that is poured into these fighters, is in combat. (This is a big reason why many Westerners do not fully grasp the role of gambling in Muay Thai. It seems to them to be just a corrupt interference in "pure sport". But in fact it is a layering of the contest of competing powers, men with soul stuff outside the ring...for better or worse. Under the spiritual logic of soul stuff fighters are never just "them". They literally invoke deities with their Ram Muay. In their Wai Kru they evoke their teachers. All of their skills and ascetic practice in training is summoned, publicly, into the ring. Fighters represent and embody.) This is not fundamentally different than the spirit-logic of cosmic battle that governed warfare in the great Ayutthayian Empire 500 years ago. What has changed is "who" is seen to have soul stuff, fundamentally a question of changing culture and values. As to the practice of Muay Thai itself, in the training kaimuay, and in the ring, one has to grasp that the fighting art and the fighting sport cannot be completely separated. Traditional kaimuay are technical houses of the inculcation in soul stuff. One is learning the practices which will give you power in a physical contest, but a contest which ultimately is also a spiritual contest. The techniques of a particular kru, the styles of a particular gym name, are a practical knowledge of Thai combat power. And the conditions of its practice are necessarily those of discipline and ascetic self control. The fundamentals of posture (ruup), timing and balance are meant to create liberty in the fighter, and its presentation to the judges and audience. Specific techniques, ways of blocking, attacking, avoiding, punishing or damaging, controlling, frustrating, overwhelming, are a kind of complex grammar of soul stuff. You display that you have more, and in defeating your opponent, in some sense you take some of their soul stuff as your own. And, as fighters share the ring with you, they too can gain soul stuff through proximate association (if you have a great deal). For deeper dives into this here I write in some detail about the social conditions of Thai training practices through the thinking of the sociologist Bourdieu: Trans-Freedoms Through Authentic Muay Thai Training in Thailand Understood Through Bourdieu's Habitus, Doxa and Hexis, and here I write about how the philosopher Agamben's study of 13th century Franciscan monastic practices help explain the rule-following power of Thai gym training for Westerners: Thailand's Muay Thai Gym, Authenticity and the Escape from Capitalism | Agamben on The Highest Poverty The importance of this insight into soul stuff and its transmittability is I believe that it unlocks much of the question about the religiosity (or spirituality) behind Thailand's Muay Thai. Often it is simply dismissed altogether because it does not seem reducible to the few obvious, formal rites that surround Muay Thai fighting. And, the magical practices of its past do not seem to embody most, or even much of any of Thailand's Muay Thai as non-Thais experience it. I suggest that the logic of soul stuff is so prevalent, so shoots-through Thailand's Muay Thai, even in its most secular and commercialized expressions, its so omnipresent it is almost impossible to see by Westerners (and others) who can carry a different cultural view of power. It though is something that is much closer to a Chinese metaphysical concept of Yin and Yang, a base assumption which explains many diverse practices, whether they be spiritual or quite secular, woven into the perspective of a culture and how it bonds together. And, as the historian O. W. Wolters argued, these beliefs lay at root beneath very diverse cultures all across Southeast Asia, spilling well over any particular country's barriers. And...if you kept the logic of "soul stuff" in mind you would get a better sense of what the difficult training in Muay Thai is truly focused on...the melding of the spiritual and the martial going back perhaps 2,000 years, as it is expressed and conceived in today's contemporary culture, and as the art of Muay Thai itself has come to embody it over the past 100 years or so. For a the primary source on O. W. Wolter's concept of "soul stuff" read here:

-

adding my commentary notes: On pages 17-19 he introduces the concept of "soul stuff", specifically in the context of the "cognatic kinship" of the lowland regions of Mainland Southeast Asia: This kinship is one in which inheritance and conceptual descent passes equally from males and females. Importantly, powers (rights and otherwise) are not confined by particular gender. These are not family trees of continuous energetic progeny, of men or women, but rather individuals are emphasized by in the genealogy, by their performance. What he is breaking away from is the idea that "power" (however it is conceived, is much less structured by institutional positioning, and not even by lines of familial descent, than by the idea that through performance one can acquire, and also signify personal power..."soul stuff". You didn't get it from your "title" or your father, per se. If you've been in Thailand long you'll recognize the "big men" of political or social power. He though places this within a larger idea of "prowess", which some sense of martial performance. (In the appendix in the post above emphasis is on spiritual performance, even to the degree of asceticism, in Balinese and Javanese cultures which perhaps DO place more emphasis on direct lineage). The idea he's forwarding though is one of almost spiritual (or even charismatic) social mobility, as endemic to mainland Southeast Asia, achieved through performance, read as "prowess". You can see this social/spiritual mobility expressed in O. W. Wolter's summation: Cognatic kinship, an indifference to lineage descent, and a preoccupation with the present that came from the need to identify in one's own generation those with abnormal spiritual qualities are, in my opinion, three widely represented cultural features in many parts of early Southeast Asia. (p. 21) He views power to be, comparatively, performatively competitive, less restricted by bestowing institution or lineage. "Soul stuff" and the capacity to have it, or more importantly perhaps acquire it and display it, creates an under-logic of a certain mobility through achievement.

-

This is a transcription of Appendix A of the preeminent historian O. W. Wolters' History Culture and Religion in Southeast Asian Perspectives (1982, 1999/2004), covering a very significant principle of his interpretation of early Southeast Asian beliefs. It is for him an essential under-belief which animates meaningful social structures within different SEA cultures, and for the study of the history and meaning of Siam/Thailand's Muay Thai it can be particularly illuminating. It's not a text I could find online, so I put it here. For larger context on how the concept of "Soul Stuff" may be used to illuminate the spiritual nature of Thailand's Muay Thai, read: Toward a Theory of the Spirituality of Thailand's Muay Thai Miscellaneous Notes On "Soul Stuff" and "Prowess" by O.W. Wolters I became interested in the phenomena of "Soul Stuff" when I was studying the "Hinduism" of seventh-century Cambodia and suspected that Hindu devotionalism (bhakti) made sense to the Khmers by a process of self-Hinduization generated by their own notions of what Thomas A. Kirsch, writing about the hill tribes of mainland Southeast Asia, calls "inequality of souls". Among the hill tribes, a person's "soul stuff" can be distinguished from his personal "fate" and the spirit attached to him at birth. "Both the internal quality and the external forces are evidence of his social status." The notion of inequality of souls seems to be reflected in the way Khmer chiefs equate political status with differing levels of devotional capacity. I then began to observe that scholars sometimes found it necessary to call attention to cultural elements in different parts of the lowlands of Southeast Asia which seemed to be connected with the belief that personal success was attributable to an abnormal endowment of spiritual quality. For example, Shelly Errington in her forthcoming book, Memory in Luwu, chapter 1, sumange is the primary source for animating health and effective action in the world, and kerre ("effect") is the visible sign of a dense concentration of sumange. Potent humans and also potent rocks, for example, are said to be in "the state of kerre (makerre)". Sumange is associated with descent from the Creator God and signified by white blood, but this is not always so. Individuals with remarkable prowess can suddenly appear from nowhere, and the explanation is that they are makerre. Kerre is not invariably contingent on white blood. In Bali the Sanskrit word sakti ("spiritual energy") is associated with Vishnu. Vishnu represents sakti engaged in the world, and a well-formed ancestor group is the social form required to actualize sakti. But sakti is Bali is not related to immobile social situations, for Vishnu's preferred vehicle is "an ascendant, expanding ancestor group." Such a group is led by someone of remarkable prowess. Benedict Anderson in his essay on "The Idea of Power in Javanese Culture," does not refer to "soul stuff"; his focus is on Power, or the divine energy which animates the universe. The quantum of Power is constant, but its distribution may vary. All rule is based on the belief in energetic Power at the center, and a ruler, often for concentrating or preserving cosmic Power by, for example, ascetic practices. His feat would then be accompanied by other visible signs such as a "divine radiance". The Javanese notion of the absorption of cosmic Power by one person presupposes that only a person of innate quality could set in motion the processes for concentrating cosmic Power by personal effort. On the other hand, the Power this person could deploy in his lifetime inevitably tended to become diffused over the generations unless it was renewed and reinvigorated by the personal efforts of a particular descendant. Anderson's analysis may recall the situation I seemed to detect in seventh-century Cambodia. In both instances ascetic performance distinguished outstanding men from their fellows, and in Luwu as well as in Java visible signs revealed men of prowess and marked them out as leaders of their generation. Again, according to Vietnamese folklore, the effect of a personal spiritual quality is suggested by the automatic response of local tutelary spirits to a ruler's presence, provided that the ruler had already shown signs of achievement and leadership. A local spirit is expected to recognize and be attracted by a ruler's superior quality and compelled to put himself at such a ruler's disposal. I have introduced the topics of "soul stuff" and "prowess" in a discussion of the cultural matrix, and we can suppose that these and other indigenous beliefs remained dominant in the protohistoric period in spite of the appearance of "Hindu" features in documentary evidence. I take the view that leadership in the so called "Hinduized" countries continued to depend on the attribution of personalized spiritual prowess. Signs of a spiritual quality would have been a more effective source of leadership than institutional support. The "Hinduized" polities were elaborations or amplifications of the pre- "Hindu' ones. Did the appearance of Theraveda Buddhism on mainland Southeast Asia make a difference? Historians and anthropologists with special knowledge must address this question. I shall content myself with noting a piece of evidence brought to my attention by U Tun Aung Chain which refers to the Buddhist concept of "merit". The Burman ruler Alaungmintaya of the second half of the eighteenth century is recorded as having said to the Ayudhya ruler: "My hpon (derived from punna, or "merit") is clearly not on the same level as yours. It would be like comparing a garuda with a dragon-fly, a naga with an earthworm, or the Sun with a fire-fly." Addressing local chiefs he said: "When a man of hpon comes, the man without hpon disappears." [my bold] Here is Buddhist rendering of superior performance in terms of merit-earning in previous lives and the present one, and we are again dealing with the tradition of inequality of spiritual prowess and political status. Are we far removed from other instances of spiritual inequality noted above? The king's accumulated merit had been earned by ascetic performance; the self had to be mastered by steadfastness, mindfulness, and right effort, and only persons of unusual capacity were believed to be able to follow the Path consistently and successfully during their past and present lives. Such a person in Thailand would be hailed for his parami, or possession of the ten transcendent virtues of Buddhism. A Thai friend tells me that parami evokes bhakti ("devotion"), and the linguistic association suggests a rapport comparable with what is indicated in the seventh-century Cambodia and Vietnamese folklore about the tutelary spirits. In all the instances I have sketched, beliefs associated with an individual's spiritual quality rather than with institutional props seem to be responsible for success. Perhaps de la Loubere sensed that same situation in Ayudhya at the end of the seventeenth century when he remarked: "the scepter of this country soon falls from hands that need a support to sustain it." His observation is similar to that of Francisco Colin in the Philippines in the seventeenth century: "honored parents or relatives" were of no avail to an undistinguished son. Others may wish to develop or modify the basis I have proposed for studying leadership in early societies of Southeast Asia. Explanations of personal performance, achievement, and leadership are required to reify the cultural background reflected in historical records, and in this turn requires study by historians and anthropologists, working in concert, of the indigenous beliefs behind foreign religious terminology. pages 93-95

-

I don't really remember their English because Sylvie spoke to them in Thai. I believe Kongtoranee though was a trainer in Singapore for some time, which usually means workable English. Cool that you did research and you feel good about it. Let us know how it turns out. Also, if you are there for a while consider taking a private with Chatchai Sasakul whose gym is not that far (a taxi ride). Former WBC boxing champion and one of the best boxing coaches in all of Thailand. There is tons of his stuff in the Muay Thai Library:

-

Adding in another connection between Greek Antiquity and the combat of Siam. Both were slave cultures, and the aim of warfare often consisted of the taking of slaves. This made the regard of an enemy quite different from that of the West where the aim was, often, the capture of (scarce) land with less regard for the enemy. The knockout, in some sense, may reflect this underlogic of Western land grab warfare, where the killing of the enemy may be a primary goal, whereas capture and control may be aims of slave warfare cultures because the captured enemy became your wealth. More on this as it relates to Thailand:

-

You'd have to hear from someone who has trained there recently, but an option to think about is Samart's gym in northern Bangkok. It's not going to be crowded like the most hyped gyms. It has the benefit of being run by Samart, perhaps the greatest Muay Thai fighter of all time, and a WBC World boxing champion (going with your background). I'm not sure how much Samart does in the training, but his brother Kongtoraneee was perhaps an even more accomplished MT fighter, and also fought for a WBC boxing championship is there. So you have a proper fusion of boxing and Muay Thai. Again, you would have to hear from someone who has trained there recently, gyms change all the time. It's kind of an off-the-circuit, but still reputable gym. https://web.facebook.com/samartpayakaroongym

-

Helpful Videos for Beginners

Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu replied to Leto's topic in Patreon Muay Thai Library Conversations

Sorry, I didn't get to see your post in time before you editing it. First posts always need approval, I missed it. -

Sylvie's made a very good comparison to food, to a nation's cuisine. You come to other cultures to eat their food. You don't come to eat your food. Yes, big business tourism will rely on giving visitors the food they are accustomed to, in hotels, in busy streets even. Hell, I am happy to find a good Hamburger after 10 years here, to be sure. But to have the cuisine literally be replaced, so that it no longer exists, so that it fits the tastes of foreigners feels like quite a loss, and actually undermines the long term potential of the culture, as an invested tourism destination. You can get that food in any country. The comparison to fighting styles is not out of place. I remember some fighters who have come to Thailand to learn "real", "authentic" Muay Thai, so to speak. They wanted to get away from the Muay Thai of their countries, where promotions are just "brawling". There was a kind of snobbery (in a good way) about coming to Thailand to fight...and then a few years on I see those very same fighters fighting almost exclusively on shows like Super Champ which are basically Western style shows. They came all the way to Thailand to escape brawl, only to find brawl. It's the same sort of thing. We bring with us our culture, often unconsciously. And we are comfortable with it, just as we are with the foods we like. I've seen this importation of Western training mindset not only in promotional rings, but in gyms too. Gyms as they hybrid between being commercial tourism houses, and as places that train Thai fighters end up absorbing some of the Western oriented training patterns and values. Thai fighters literally end up being trained more like Westerners. The entire fabric of Muay Thai becoming strained.

-

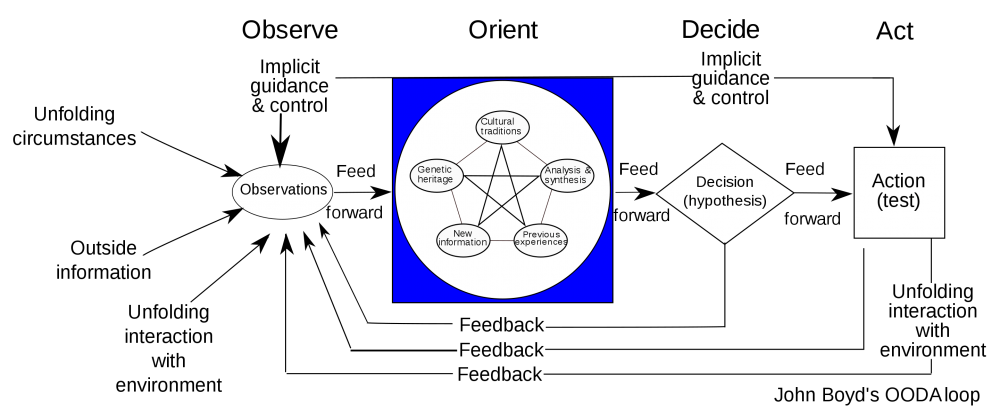

There is another suggestive productive branch to the Free Energy Principle application to Fight Theory in John Boyd's military thinking about combat and his model of the OODA loop. If combat is a form of information warfare, seeking to stress the opponent with information overload, John Boyd's fighter pilot derived theory may provide rich resource for thinking about where information entropy can occur. wikipedia on the OODA Loop.

-

This is a really interesting point. As Westerners (and other non-Thai cultures) import their values into fighting promotions, the kinds of things they want to see expressed and embodied by fighters, then I think it does also stand to reason that meaning of the training and fighting of children and young fighters also changes. The point of Muay Thai, traditionally, is not violence. It's not even aggression. It could be said to be about self-control, and the control over your opponent. If you change the point of fighting, then you have to ask whether this legit is something you would even want children to learn. You don't want to train children or even young fighters to be violent. Right? This is really the source of a lot of the Western misunderstanding of young fighting in Thailand. They've assumed that the purpose of fighting is what fighting is like in their culture. They miss the value-system of Thai fighting. In many ways its the opposite of what they assume. But, once they succeed in changing the Thai value system, so that fighters express different values...then their criticisms start to have more traction. They've turned fighting into what they believe fighting should be.

-

I think CTE is going to go way up, due to the influence of these promotions. Way up. A few reasons why: 1. Defensive excellence is being downgraded in terms of score, so fighters literally will not learn it. 2. There is going to be a lot more head hunting, which isn't the traditional form of fighting. 3. Thais learn to fight at a younger age. To some degree this is mitigated by the strong emphasis on control and defense oriented scoring, the lack of head hunting. But put 1 and 2 together, and bring it to younger fighters, its going to be epidemic. It's really hard to speak now about "Muay Thai" because even within 5 years the sport has significantly changed, and maybe more than once. Fighter skills have devolved, generally, over the past 15-20 years, but now with Entertainment Muay Thai driving the sport you are seeing very different fighting skill sets (less fluent). And, one imagines its just going to get worse, unless there is a backlash in Thailand. Traditionally though, the knockout wasn't chased in the sport, and the defensive awareness and boxing acumen of most fighters kept everyone pretty safe. We've met and known many, many high fight veterans and legends of the sport and almost none of them exhibit obvious signs of CTE. And most of those that do, that I've thought to take note of, have also fought in other combat sports after their career.

-

Muay Thai legends WBC fights

Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu replied to Nightshade's topic in Patreon Muay Thai Library Conversations

These are really great observations. Perfectly said. -

Muay Thai legends WBC fights

Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu replied to Nightshade's topic in Patreon Muay Thai Library Conversations

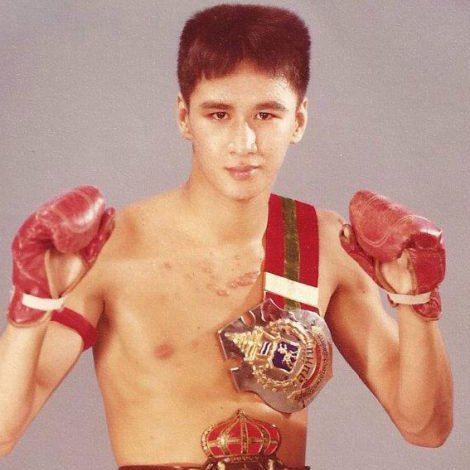

Nice idea. I'm not sure how many there will be, but here is Chatchai Sasakul vs Manny Pacquiao. Manny wins his very first world title: -

My first fight

Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu replied to Misael Lucas's topic in Muay Thai Technique, Training and Fighting Questions

I think that with first fights its important to just lower expectations. They are a mental blur. It will be very hard to execute what you feel you know, and because first time fighters tend to hold their breath under the stress they gas out quicker than they think they should or realize. I think just get your cardio up to give you a bit of a buffer, spar as much as you can with an emphasis on relaxation, and go into the fight expecting it to be more out of your control than you think. If you can relax, have solid defense, and enjoy the first fight experience, you've already won. The whole point of first fights is so you can get to your second fight. -

Entertainment Muay Thai, in Thailand, are the 3-round fight formats that change the rules and style of fighting, eliminating clinch and strongly discouraging retreating, defensive fighting. In Thailand, it began with MAX Muay Thai. As the original promoter explained, the new ruleset was designed to help Western fighters win vs Thais, with an unspoken sense that it was kind of a reversal of Thai Fight (which at the time was the most popular MT show on television, a promotion which was designed to highlight Thai greatness, often with lopsided matchups. The Entertainment model was designed to do the opposite. The ruleset was anti-Thai, and for the first few years (at least) it was regular to see mismatches that favored Western fighters, vs lower level Thais. It was designed for Westerners to win, or at least win more frequently. The Channel 8 fights were a spin off of the MAX promotion, with their own differences, but also within the Entertainment model. And since then the Entertainment model has taken hold across Thailand, at least in areas promoting tourism. The Entertainment model, I believe, was also used to evade the control of the Sport Authority of Thailand. These technically were not "Muay Thai fights", they were "shows" for entertainment, so could produce a non-Muay Thai mode of entertainment. ONE also has followed this model of changing Muay Thai, in a way that favors non-Thai fighters, I suspect so Chatri could produce non-Thai "Muay Thai" champions which are helpful for his marketing his promotion to the West. The ONE version of Entertainment Muay Thai has now been brought to Lumpinee Stadium, which no longer is a National Stadium (in the old sense) and which no longer, for the most part, hosts actual "Muay Thai" fights in the traditional sense.

-

Sorry, I didn't see this post. I actually think Dieselnoi knees would be somewhat effective in a K1 ruleset, in that they aren't overly dependent on the clinch lock, and a lot of them come in space. Yes, he locks to finish fights, but a great of what he's doing is in space, and having to do with length. But, in practical terms, it really would depend on how heavily knees are scored by judges, and how dynamic you could become with them. His technical level was incredibly high, just in terms of power, precision & drive.

-

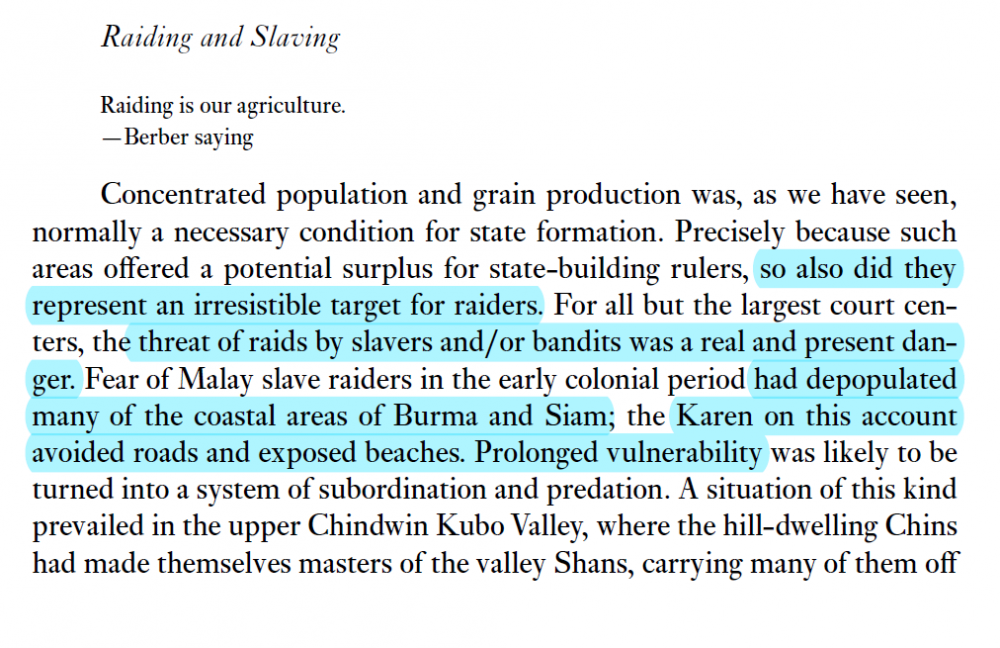

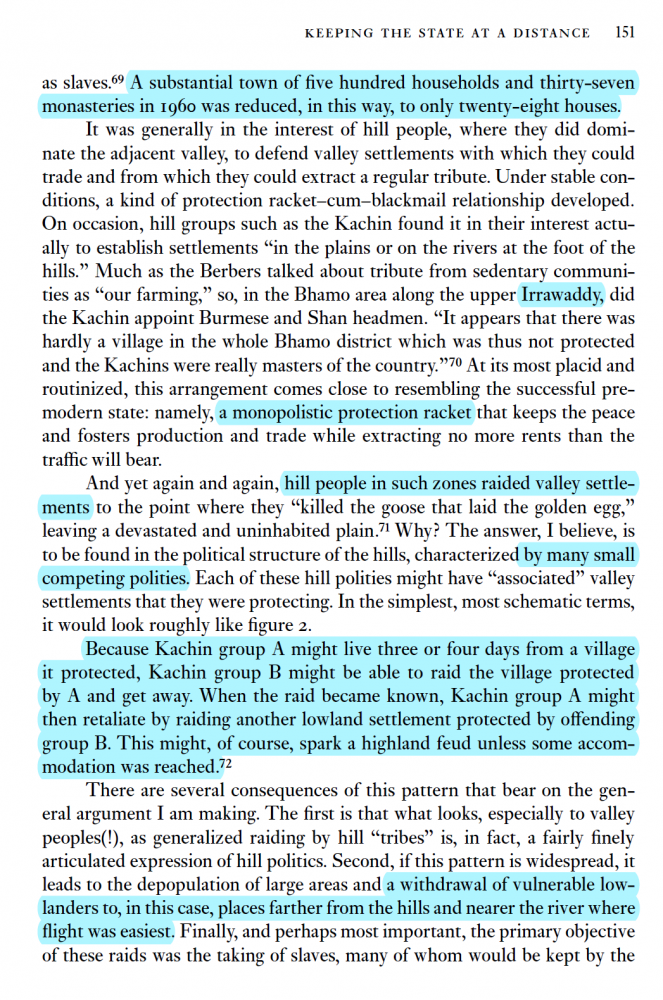

Scott finally takes up the dynamics of regular slave raiding. He is in particular interested in the littoral-edge between the valley and hills, but his logic seems quite probable within valleys and plains as well, between small polities, protection spheres, rural elites, a general agnoism of Dry Season warfare and capture. screencaps at length

-

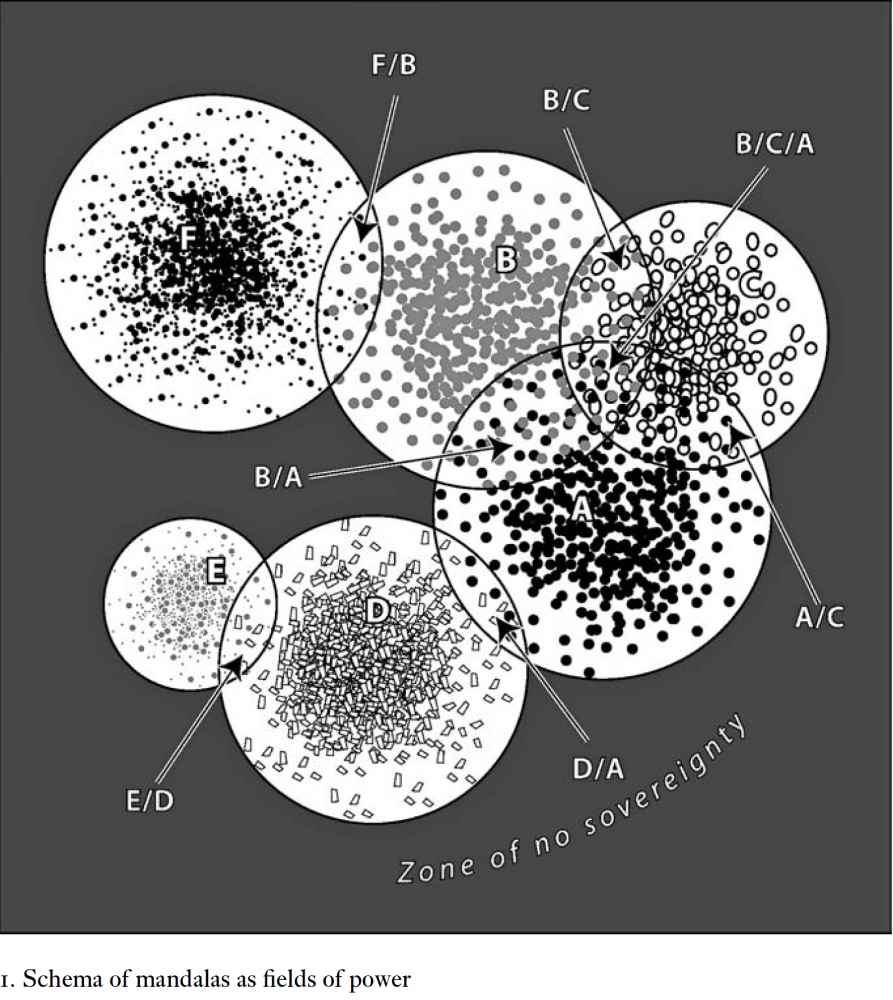

Here is a proposed set of dichotomies of values involving mandala power. Near the core, and extending out toward the ebb. These values are sometimes from the perspective of the inside, sometimes of the edge, and can express themselves conflictedly within relations, within mandalas, given their shifting sphere. Important in thinking about this is that there is no pure "outside" of mandala power. Mandala powers are nested and overlapping, so these values become relative to specific centers and their sphere of influence.

-

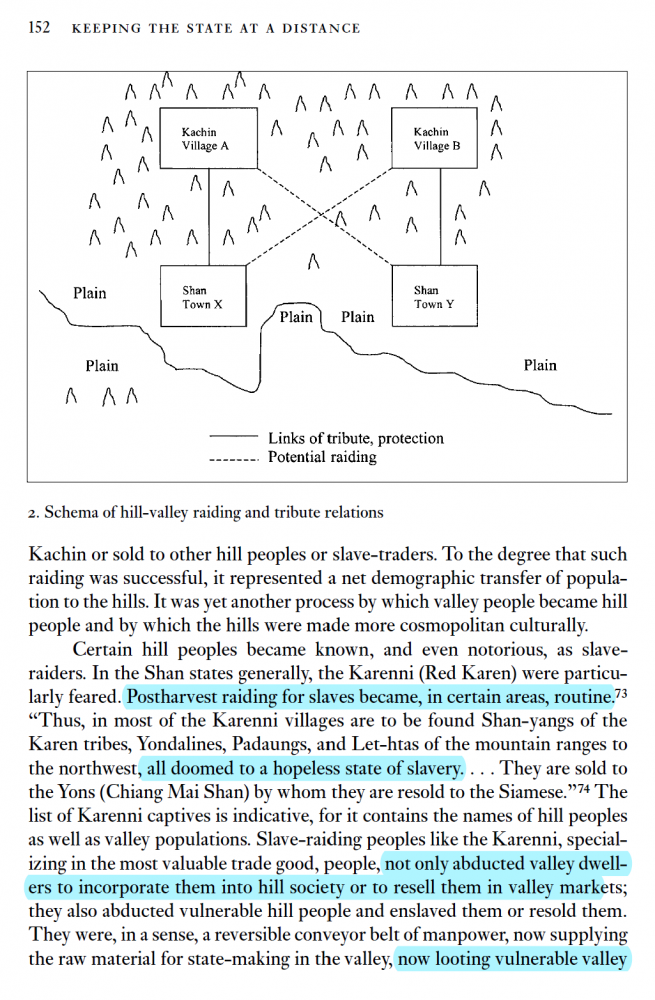

Let me bend back to this notion of mandala, which historians use to describe how political power was conceived of in Southeast Asian, pre-colonial states. There was no notion of a Nation, or even a country. There was no ideological boundary which defined one's powers or rights. Rather, a Kingdom was defined (and experienced) as a sphere of influence. It's authority went as far as it could extend, not unlike candlelight only goes as far as candlelight goes, in the darkness. And, because ancient Kingdoms considered themselves centers of elevated civilized authority, founded on an Indic concept of royalty wherein the King expressed divinity, the darkness at the edge of that candlelight was seen as primitive, animalistic, savage. Where land was plentiful, and population sparse such concept of madala candlelight was variously easy to establish. Art centers, ritualistic royalty, confluences of international trade became the heartbeats of regions, and because these mandala's of power were fed by surrounding wet-rice field padi agriculture, the more manpower (often slaves) one drew into one's realm, the wealthier and more stable a Kingdom would become. But...mainland SEA had many mandalas over the centuries, and these mandalas competed, often for that manpower which made the candlelight shine bright. There spheres of influence overlapped, not only geographically, but also in terms of time. This graphic from The Art of Not Being Governed shows the idea: But, for our purposes, these mandala of power, these orbs of candlelight, probably did not just exist at the level of Empires and Kingdoms. The modes of symbolic power, on the Indric model, likely extended itself in imitation, across much smaller regions, even village to village. These are all nested, competing spheres of power, all overlapping. If you've spent a great deal of time you likely have run into this, not at the level of Kingdoms, but within Muay Thai itself. Individual gyms have spheres of power (candlelight), individual promotions, (the much bemoaned power gamblers), city officials. Regional Muay Thai - just to use an industry and art example - is often defined by competing and overlapping mandalas of local power. (The above graphic is meant to describe Kingship & nobility mandalas of power in 17th century Siam, but one imagines could just was well ethnographically describe dynamics of power in Muay Thai, in a contemporary city.). Westerners are starting to discover that even moving between gyms in a local scene can produce significant problems, because everything is held in a network of hierarchies and spheres of reach. Even if modern Thailand, far removed from the 17th century, these spheres of reach and power define the way that power, legitimacy and authority exercises itself, symbolically and in realpolitik terms. It is not too far a reach to suggest that even though these micro-mandalas of overlapping spheres of power have not been recorded by written history, they made up the fabric of the lived, political landscape of Siam. And, because - as anthropologists rather widely argue - wealth was made of manpower, and manpower was largely composed of slave capture, the economics of even small spheres of candlight made for a constant agonism of capture. The great wars and captures of history - the worst from the Thai perspective being the fall of Ayutthaya in the 18th century when Burma took an estimated 30,000 slaves back, repatriating many of them within a hierarchy of labor - are what has been written, but countless and likely endless skirmishes & perhaps annual battles made up the living calendar, year to year. The Dry Season, which today is the festival season in the provinces, was also the War Season, and the season for Elephant capture. Following the rains of monsoon, upon harvest of rice, any locality faced the prospects of contest and capture, a real of martial tension.

-

One of the more interesting struggles in any attempt to describe the origins of Thailand's Muay Thai as an essentially Thai fighting art falls along ideological lines between an urban, cosmopolitan elite (Bangkok and before that Ayutthaya) with its very important royal patronage, high-culture shaping and international influence, and provincial Muay Thai, organized around networks of villages, provinces and various local centers of knowledge. Is Muay Thai of Bangkok? Or is it of "the people" (ie, of provincial development)? While Muay Thai's very thin pre-1900 history is coded in royal record, and the stories of capitals, it is perhaps likely that there was something of a loose dialectic, tides of development of martial prowess & necessity, between the centers of warfare's, occasional, great military sieges of Capitals of Kingdoms, and what may have been a continuous local agonism between shifting centers of local power, in regions that now are Thailand's provinces. It is this unrecorded life of shifting agonism, focused slave-raiding skirmishes (not the seizing of territory as in Europe), the need to know how to defend, capture & escape that would be woven into the fabric of the land, complimenting the warfare centers of Siamese culture, in an ebb-flow sort of way. In thinking about and researching this there were two texts that I found really interesting. There is the essay "Southeast Asian Slavery and Slave - Gathering Warfare as a Vector for Cultural Transmission: The Case of Burma and Thailand" (the article here) which describes the way that large scale slave capture between SEA capitals became avenues of cultural transition, and James Scott's account of SEA hill people in The Art of Not Being Governed. Both works brought out the idea that it may not have been the actual bloodiness of large battles that was the dominant reality of martial awareness, so much as the slave-capturing (and other manpower) dynamics of political power itself, especially as it resided in cultural capitals like Chiang Mai or Ayutthaya, or eventually Bangkok. What Scott argues - apart from his much larger claims to a kind of hidden country of highland peoples which he calls Zomia - is that there was an ebb and flow of populations which variously were captured by mandala powers (city centers of Statelike authority) and which also fled from them, often away from valley centers, and sometimes up into hills or forests. Hills and forests became associated with the uncivilized and barbaric within the dominant Siamese culture, and those value judgements came to be spread across the land in a spectrum, centered in the Capital of Kingdoms. For the purposes of thinking about the origins of Muay Thai these tidal dynamics really flesh out the possible details of what combat consisted of, year upon year, and are suggestive of its possible influences through need. Rich city Kingdom centers like that of Ayutthaya not only engaged in occasional long-distance warfare marches, capturing slave manpower, they likely also exercised annual warfare capture of much lessor scale, replenishing the manpower drain that Scott suggests was continuous (one would imagine). And, provincial, village life, across sparsely populated valleys and plains, may also have faced continual more localized security issues, in the Dry Season, when slave capture warfare began, even annually. In otherwords, perhaps like in the American West (creating a very loose analogy) where there were large scale armed expeditions and wars, there were also sparsely populated demands for family and clan security as well, village & wat centers of security and identity, a fabric of local martial competence and its regular development. Mandala power (centers of influence and patronage) did not likely exhibit itself only in the great cultural orbs of civilization which have made up our historical record, but likely also were found on a much smaller, imitative scale, overlapping spheres of influence of rural elite, or village autonomy, all within the shadow of the manpower economic demand that anthropologists argue comes with plentiful, fertile land and a scarcity of labor. The capture of others was the regular means of developing wealth, afixing identity, and protecting one's own, and there is evidence that this process of wealth concentration, as culture, was practiced and imitated down to the small scale, even quite far from kingdom centers. In short, the sparsely populated villages of the land had martial need to know how to defend themselves, escape & likely also capture. Scott likes to set up a basic dichotomy between large States (anchored by Capital centers) and the hill/forest people that evade them, but the fabric of incorporation and localized, shifting liberty likely was far more nuanced, geographied, even fractal (in terms of smaller and smaller mandalas). For me the main contribution of his approach is the idea that in the story of Muay Thai development there was a kind of ebbing & flowing dialectic of people, culture and skill that came from both city centers and rural identity, and that back and forth this wove together the fabric of what would become Siamese Muay Thai (1300-1900). A warp and weft of Capital vs village which still expresses itself in today's Muay Thai in Thailand, according the ideological sway. As I've suggested in the past, even Muay Femeu vs Muay Khao classic Golden Age dichotomies can express this fundamental divide, city vs rural. And in thinking about how concepts of retreat from the Capital still play out, even our recent documentation of Samingnoom's return to the simple life of Buriram, away from Bangkok Muay Thai, to a hand-built house and a small neighborhood ring, embodies something of this ethic of liberty vs civilization, land vs city, each of which can be idealized. Quite telling in this attempt to piece together elements of Siamese history which have not made it into the dominant written record of Kingdoms, or the lasting architectural remainder, are stories of how armies would devastate and capture, not in their battles, but simply in the marches, consuming an estimated 26,000 square kilometers in even a 10 day march. These thoughts develop from this point in this thread:

-

James Scott on the "path of war" devastation of large scale Siam war expeditions. It wasn't necessarily the battles which produced hardship, it was the paths of armies, and "booty capitalism" which could enslave: AND, (note the first reference to smaller, more frequent campaigns, not yet speaking of more nested, localized combat) small vassal state banditry mentioned (p 150)

-

That is a very good question! Sylvie's dying to fight but things have become very difficult in Thailand, and its very hard for her to find fights at all. The combination of COVID over the last 3 years, and the dominance of 3 round Entertainment Muay Thai has had a serious impact on the female fighting we once knew, and, it seems that Sylvie's reputation as a fighter has cleaned out almost all possible opponents, at least opponents we can find and that promoters have tried to book. The first problem is Entertainment Muay Thai itself. It is a mode of fighting that is designed to help Westerners win, and is pretty far from the Muay Thai that Sylvie came here with passion to learn, so Sylvie has tried to hold a firm line in trying to fight in the traditional 5-round style. It's why she fights. This means that there are fewer promotions and fighting opportunities to choose from. It's really become something of an ethical stance for her, as the encroachment of Entertainment fighting is actively eroding the art of Muay Thai itself, in our opinion, and if she can she doesn't really want to become an advocate for it, if she can avoid it. Who knows how long she can hold out? COVID for the last couple of years also impacted female Muay Thai in that a lot of the strong local fighters that Sylvie used to face, giving up a lot of weight, have retired from the sport, so there are fewer possible opponents. Areas where we used to fight very frequently, like in Chiang Mai, simply cannot find opponents for her...we are told. There may be opponents in the provinces, there should be, but provincial fighting is pretty insular, and its been difficult to find matchups there. Everyone wants her to fight someone near her weight (for gambling purposes), but there seems to also be the feeling that she's too strong to fight someone near her weight. A top fighter near her weight has turned down 3 different promoters for a match. So we are in a catch-22 situation. Too strong of a fighter, by some reports, and provincial gambling fights don't see giving up big weight as appropriate. This has to do with the culture of fighting. We have several people looking for fights in the provinces, which hold the best traditional fighting in the sport for women, but none of them can find a match. We can't really seem to crack into Phuket fighting, can't fight in Chiangmai for lack of opponents, local traditional shows like those in Hua Hin can't find anyone who wants to fight Sylvie, and provincial fighting is very difficult to book. It leaves very few opportunities at this point. Sylvie is an exciting fighter and Thais love her when they see her fighting, so it really is just a matter of finding our way into new fight scenes and people enjoying it. All these problems were exacerbated by a significant injury Sylvie suffered, being thrown from a horse into a concrete fence, which really scared us. Luckily she avoided serious injury, but she was immobile for a few weeks, and it took 6 weeks or so to get back to training. So the hunt for fights took a hit in that time as well. So, Sylvie's been training as if she has a fight. She has one lined up in a few weeks (but fights and fighters have pulled out several times lately, so we are just crossing fingers). She's developing as a fighter, sparring with Yodkhunpon every day. It's all good stuff, but Thailand is going through a phase right now, in female fighting. Hopefully the trend will swing back toward traditional fighting, and female Thai fighters will become more numerous now that COVID shutdowns have relaxed. That's the long answer. The short answer: It's very hard to find fights right now, Sylvie would love to be fighting several times a month, we'd really drive anywhere in Thailand to get them. We are doing everything the same as before. Working hard on the Muay Thai Library project, Sylvie's pushing herself as a fighter, developing in training, and we are looking hard for matchups.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.