Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 11/21/2023 in all areas

-

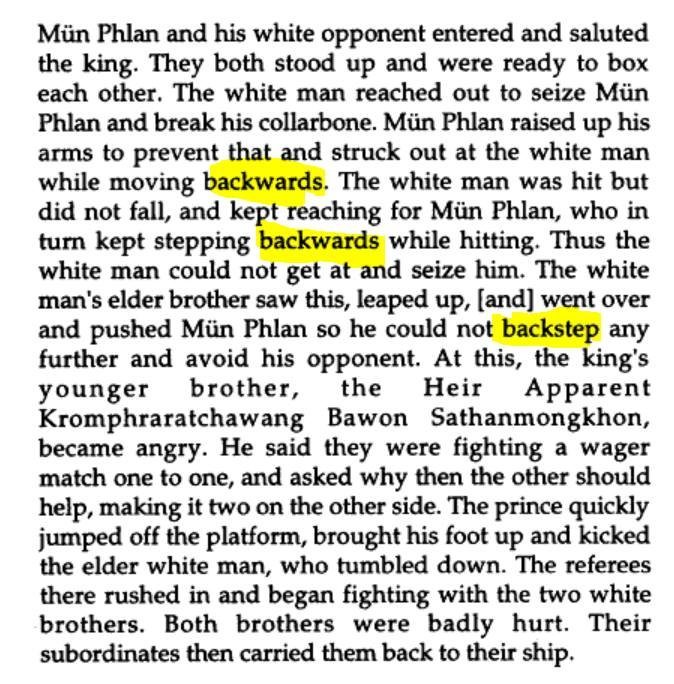

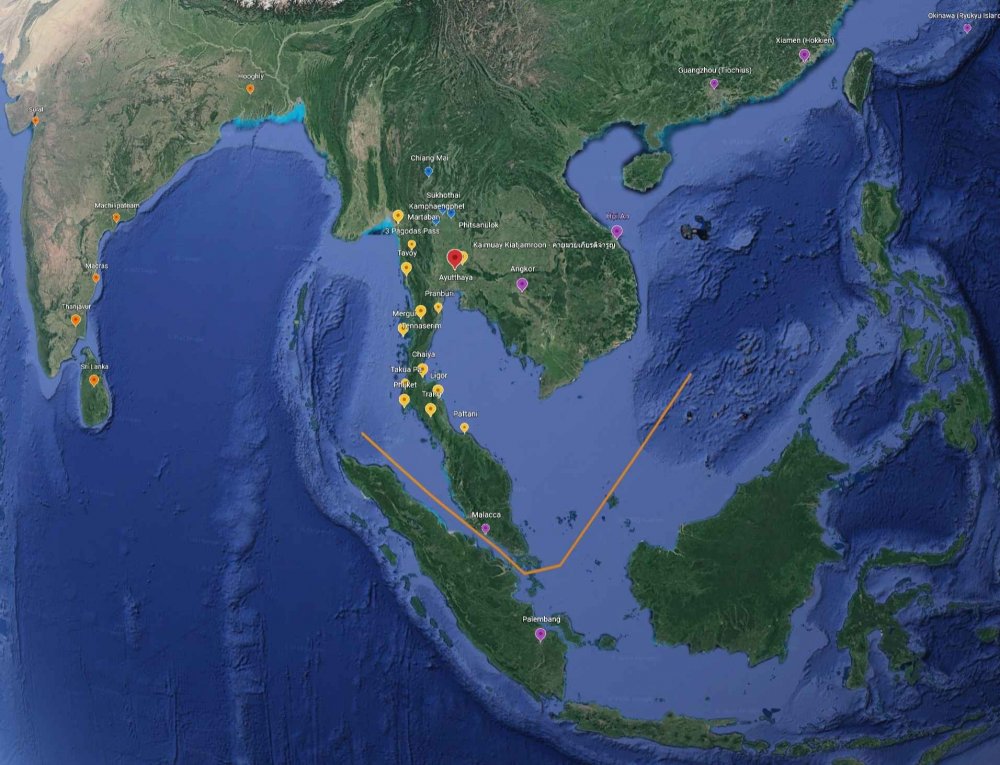

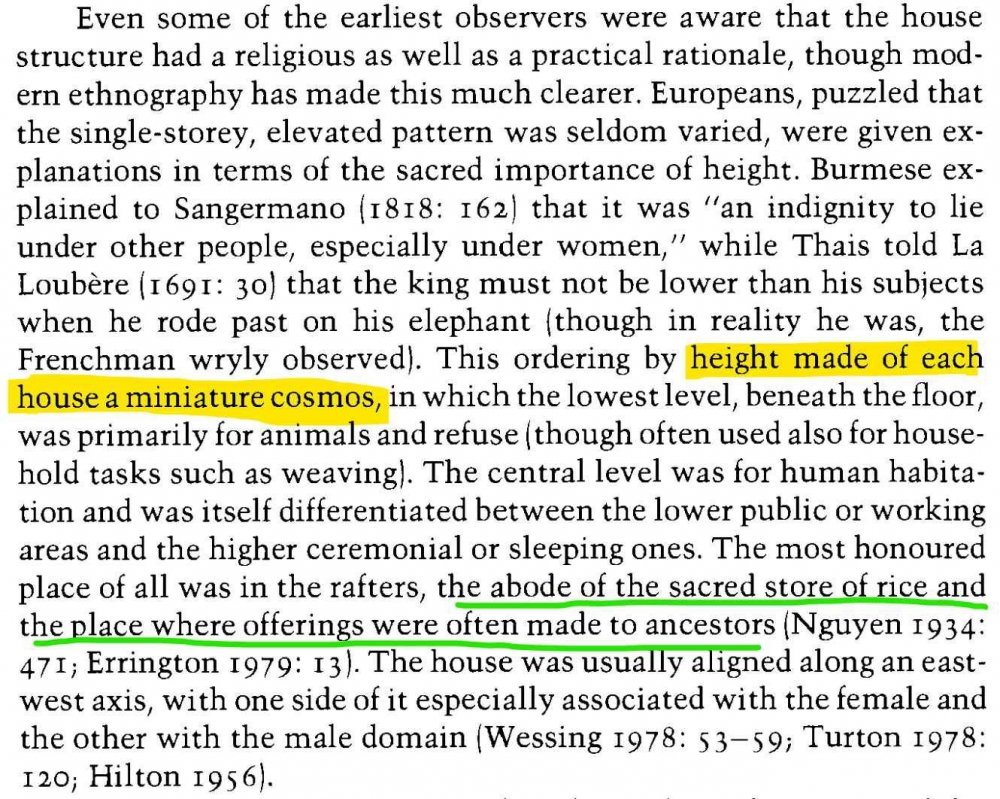

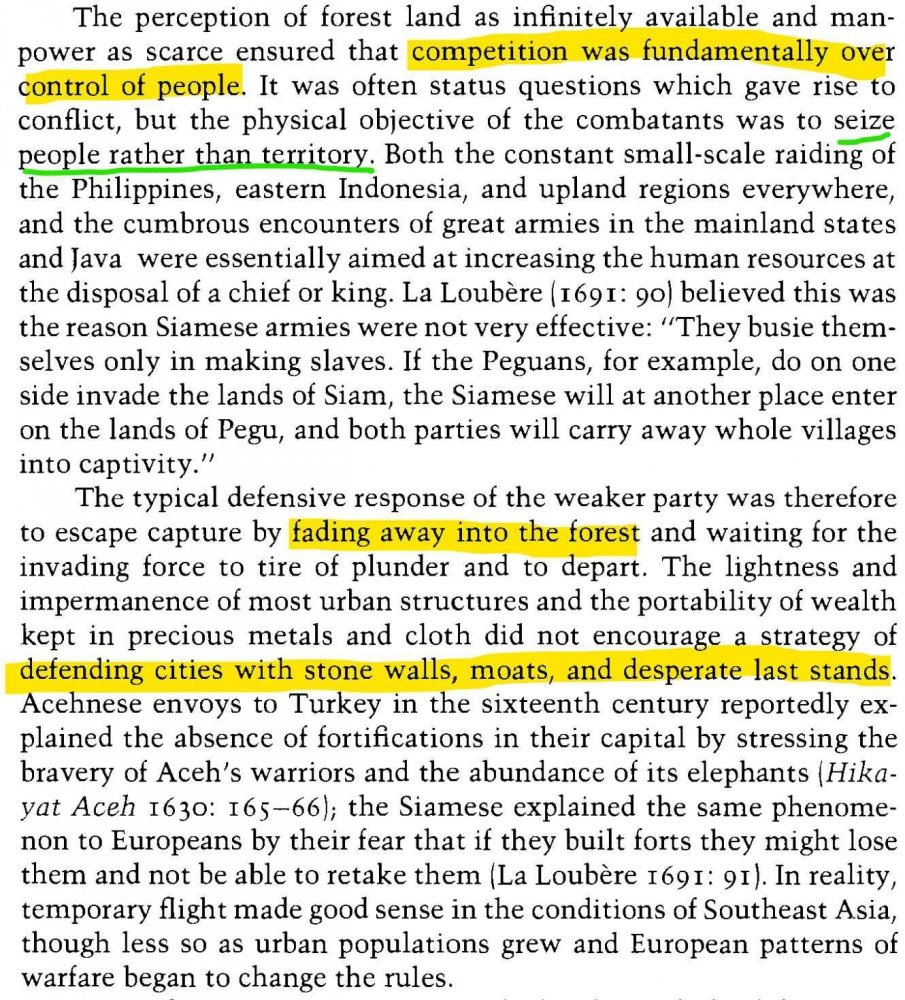

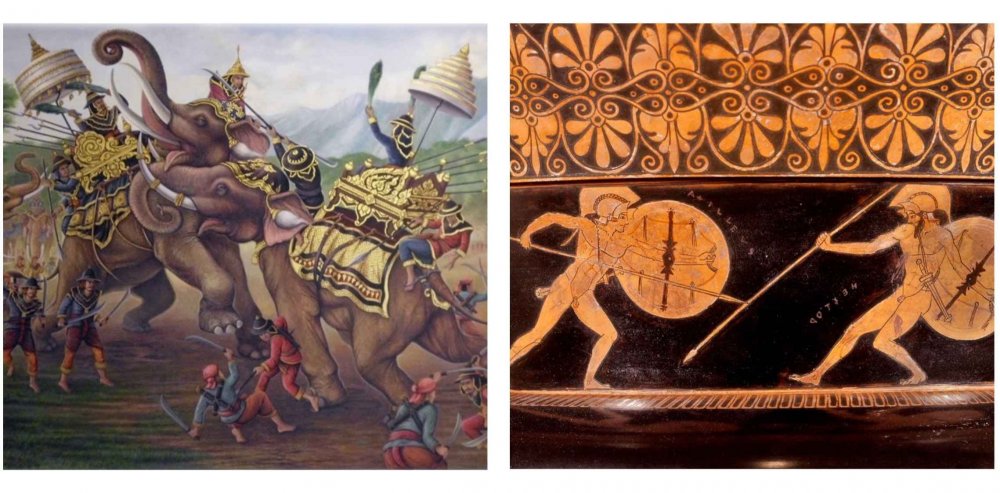

Below is a string of readings, mostly organized around the history of Siamese and Southeast Asian culture, discussing the possible historical foundations of a distinctly defensive orientation to Thailand's Muay Thai. They do not compose a single argument, but rather are read as extensive notes, with each post working somewhat additively & independently. When a Frenchman Fought the King's Champion 1788 I've always been fascinated with the historical account of two French brothers fighting a Siamese champion in 1788. It is not only the oldest account of Siamese/Thai fighters facing off against a Westerner, it almost surreally acts out a fundamental misunderstanding between Thai and Western cultures which plays out to this day. Teleporting across more than 200 years it somehow explains the profound misunderstanding of how Thailand traditionally sees fights, and even helps explain the new "entertainment Muay Thai" type of promotional model of fighting, designed to help Westerners win fights in Thailand and abroad, by finally getting Thais to stop going backwards. First the account: The French fighter finds it incomprehensible why the Siamese champion is fighting in an evasive manner, especially when honor is so much at stake. The occasion is so humiliating that his younger brother jumps in and shoves the Siamese fighter so he cannot retreat. He is trying to force him to "stand his ground" in what surely was Eurocentrically imagined to be a "manly" and proper way of conducting a fight. I am reminded of when MAX Muay Thai (the first big promotion of "Entertainment Muay Thai") opened in Pattaya and Thai fighters were given instructions that "If you go back you will lose" when fighting the Westerners the promotion had in mind. This was actually written in Thai in the early days of the promotion in the handout they gave to fighters; there was no corresponding message in the English rules. In terms of commerce the argument was that this was to make fights more exciting to the average viewer, and this is certainly the kind of product they created. Lower skill level, often smaller Thais facing off against Western fighters under circumstances which favored the Western fighters, and produced many Western wins. Thai fighters who in their art had become excellent retreat and counter fighters - mostly due to the traditional scoring bias that rewards counter fighting, and a fight culture which reads the retreating, defending fighter as in the lead (quite in contrast with how Westerners can read retreating fighters) - were being stripped of perhaps their greatest weapon, space-taking counter fighting, to level or even tilt the playing field the other way. And indeed it took Thai fighters on the promotion perhaps more than a year or two to adjust to this fundamental change. No matter how many times they were told "Don't go backwards!" in these early years they still instinctively retreated when they had the lead. Reading the account from the 18th century, and the infuriated response of the French brothers hauntingly echoes forward into today's Entertainment Muay Thai shows. There must be something essentially Thai/Siamese about the retreating fighter for this cultural contrast and misunderstanding to have endured for more than two centuries. I've always argued that the answer to this is found within Buddhism itself, and how it regards the hotter emotions such as aggression, anger, fury, etc. Buddhism sees these peak emotions as a loss of control, whereas Westerners (and other Asian Cultures) may read them as peak experiences of self-expression, willing & desire. The Buddhistic appraisal of aggression and anger is an upside-down world to other cultural values of angered affects, and this played out in the form of traditional Muay Thai itself, giving shape & tremendous skill to the Thai fighter in a broad sense. (Traditional Muay Thai does have its own ritualistic contrast of defensive arts vs aggression in the customary contrast of Muay Femeu & Muay Khao pairing, but the ideological importance of that conflict is something not to dive into here, it's enough to understand that the overall bias towards reading the defensive, retreating fighter as the one who is in control, both of himself and his opponent, is a bias which has produced perhaps the best defensive fighters in the world.) For a long time I have used this Buddhistic explanation of the affects as a satisfying answer. But I was taken by surprise when reading about the history of Southeast Asian culture to discover that there are likely older, materialist explanations for the favoring of retreat in battle, aspects that likely blended well with Buddhism's prescriptives about the hotter emotions. What follows does not assert that there are no property, boundary-driven identity concepts in Thai culture, or in warfare. In fact Thai & likely Siam culture was diverse and historically quilted. Territoriality & fluidity are likely best seen in tension. There definitely has been territoriality and in a modern Nation State it can certainly be pronounced. Instead what follows draws out a particular history of a differing kind of economic martial logic in Southeast Asia & Siam, one that can lead to Western confusion. Wealth was Labor, Land Was Cheap (opposite of Europe) territory & identity I'll be citing from Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: The Lands Below the Winds, by Anthony Reid, which proposes a commercially driven trade-culture that perhaps developed over thousands of years, linking and extracting from the two great cultural powers of China and India. Many in the West, including for a long time myself, think of Thailand (and Siam) somewhat in isolation, a distinct and almost unicorn culture (and in some ways it is), but the Ayutthaya Empire was a maritime, commercial trade empire, one of dozens that rose up and lasted for centuries at a time, over the millennia. Anthony Reid's book attempts to describe the culture of this region in more comprehensive terms, especially in the time of its greatest commercial power. In the map above you can see Ayutthaya positioned along this trade route (on a river route to rich Northern Siam trade resources, and connected to the sea by that river); but the Southeast Asian culture Reid is describing covers the entire trade basin, stretching down to Java and Sumatra, over to Vietnam and the Philippines, and up into the north below Chiang Mai. Thought to be much like Europe's incredible rich Mediterranean basin which connected Northern Africa, the Levant & Middle East, and Europe, this Southeast Asian basin of trade produced a flowering of culture, positioned between China and India. Reid's descriptions are of this basin culture. The first thing to note is that, broadly speaking, individual houses were made of perishable materials. The only buildings that were made of stone were palaces or temples. Transitory human habitation organized itself around symbolized permanence in the stone-built temple. Just in terms of architecture and practice we already see a contrast with Western values (at least how they came to be). The wide-spread perish-ability of personal housing made it such that rebuilding a house, or moving a house if damaged was relatively as easy as repairing it. Already one can be tempted into seeing the wood & thatch transience of human life in a Buddhistic sense, compared to the stone truths of religion (or royalty). Houses literally were built to be discarded in the event of raid or war, or nature's damage, which seeds a difference in how one regards one's personal space, and where identity is located. If we account for the idea that one's abode expresses one's personal center we can see that perishable, moveable housing presents a different conception of "self". But, this does not mean that housing was without meaning. In fact observers noted that the SEA perishable house was highly ordered. It presented a cosmos in miniature. This high-low hierarchy of holiness is expressed in Muay Thai scoring to this day (as well as pervading the culture). Houses were often raised off the ground to survive flooding. The ground was where waste and animals were kept. The family wealth of rice & ritual objects were kept in the rafters. Most important though, in this context of perishable housing, is how territory itself was perceived. Anthropologists of the world over make a very large distinction between cultures that develop in two ways (there are of course complexities and variations in this). There are cultures where land is widely available (cheap) and the thing that is scarce is the labor to work it (expensive). And there are cultures where land is scarce (expensive) and the labor is plentiful (cheap). As Reid describes the SEA culture of this era it is definitely of the former. If you would like to watch a very good lecture explaining the deep cultural ramifications of whether it's land or labor which is scare I highly recommend anthropologist David Graeber's Debt, Service, and the Origins of Capitalism (1 hr, 17 min) Again, very broadly speaking, there are two economic flows at this time: city state/empire mercantile powers which are centers of maritime trade, and those that develop out of a plenitude of land and the scarcity of labor. The 600 year Srivijaya maritime empire (tweet link below) is a good example of a mercantile sea trade power. The Siamese Ayutthaya trade empire arose after the Srivijaya fall. For our purposes, thinking about how territory, identity and battle was conceived at this point the focus is on this fundamental economic dyad. A plethora of land, a shortage of labor to work enough of it to build wealth. Ayutthaya was a maritime trade power, drawing influences and wealth from all over the world, but it was surrounded by land that needed to be worked. And just north of Ayutthaya was even more fertile land. There is one basic answer to this question of labor...slavery. And in fact all over the SEA trade culture of labor scarcity the raiding of villages and cities for slaves was the primary engine of wealth development. Warfare was much less battle over territorial lines (over well-defined and defended spacial identities) as it was for the capture of slaves. All over SEA the impermanence of housing, the portability of wealth (precious metals, rice), and the scarcity of labor and the plenitude of land produced the core reality that retreat was far more effective than standing one's ground. In fact militarily battle was understood in a much more fluid, spatial way. Fortifications could be over taken, and if lost could themselves provide enemy anchors which would be hard to unseat. Instead battles were considered like waves of raiding. The enemy would come, capture, plunder and leave. For Western observers this mode of warfare was not esteemed, in fact it defied basic Western concepts of martial strength (produced by cultures where land is scarce and labor plentiful, the exact opposite of SEA's economic reality). You can see the possible, deeper origin behind Western conceptions of fighting (fortified, territory-oriented) and their confusion over SEA fighting (fluid, retreat-oriented), as exemplified in the 1788 fight between a Siamese champion and a Frenchman. These are two different martial logics. In fact in SEA there was an intersection between martial logic and commerce expressed in the architecture itself. Below is the lesson-learned example of Dutch traders building a stone storehouse for their goods, which they then fortified into a small castle from which they could not be uprooted. In the fluid world of raiding warfare and slave-taking wealth stacking stones was a significant martial danger, and in fact forbidden, or taken as an outright threat in some principalities. One can see that these are very different worlds produced by different economic (materialist) foundations, a different sense of what warfare and battle is. I'm going to leave aside the other half of this equation, making only a note here, which is that: these are maritime trading powers, and that water itself was a medium of culture whose properties manifested in tendencies opposite to those traditionally attributed to land. There is a historian's adage: "Land divides, water unites". Land encourages drawn lines, and the battle over those lines. Sea culture is much more spatially fluid, less visually distinct and demarcated. What is not included in that adage is that land (when land is scarce) is much more divided/territorial, but land (when land is plentiful) can also be fluid and less demarcated, when it is labor that is scarce. Maritime trade navies, mercenary warriors, sea-battles (and fighting styles that involve piracy and on-water fighting), because watery, produce a very different fluidity to the notion of power, authority and wealth. There is much less of a sense of "high ground" which would be citadeled and defended, and instead a more tactical topography of techniques. And water produces wealth through connection (exchange), not through isolation. Martial wateriness exists in the context of exchange & the lasting of connections. The fluidity of land based raiding, slave-taking warfare over perishable housing that encouraged retreat was mirrored by the spatial fluidity of maritime power and trade-lanes. In a sense the land can have a kind of maritime fluidity as well. Some Battles Not Very Bloody There is a very significant dimension of warfare in the context of slave-wealth, which is that you do not want a bloody, kill-everybody rout. Once you get to a point of dominance in a battle you are just killing off-your own wealth when you kill an enemy. The purpose of the raid is to capture, not kill. I'm not going to say that this is conclusive, but it certainly evokes the wide-spread Western confusion on why there are so very few knockouts in Thailand's traditional Muay Thai. Legends of the sport in the Golden Age might have 100s of fights but only a handful of knockouts. (Even Muay Boran knock-out-or-nothing, rope-bound fighting, an older form of sport Muay Thai, may have more been fights of attrition, much as the bound boxing fighting of Greeks & Romans.) The aim of much of contemporary Western fighting - the decapitation of the opponent - is missing. I talk a little about this cultural difference in this article: The Cowardice of the Knockout - Hellenic Greek Concepts of The Beauty of Boxing. In the larger sense, in SEA warfare was not about killing your enemy. It was about capturing and controlling them. This is to this day a foundation of Thailand's Muay Thai scoring (though this ethic is being challenged and changed by the new Entertainment models): The idea that you would be only "shedding your own blood" if you killed an enemy is quite alien to some of the Western concepts of warfare, because of the fundamental land vs labor equation. In SEA the fluidity of raiding battles, the value of retreat, the desire to control and not maim your enemy ended up producing a very important "symbolic" or signifying dimension to fighting, one in which a winning side demonstrates, (through skill & even magical superiority) that by cosmic forces they were destined to win. In fact, much as in Ancient Greece in the West (in the Iliad for instance), at times the battle was symbolically waged between charismatic leaders. Above, King Narsuan's elephant duel, and the battle between Achilles & Hector in Greek literature bear resemblance (the story of Nai Khanomtom, the purported father of Muay Thai is another example of symbolic warfare, but in this case as a captured slave), as they both idealize champion vs champion symbolic fighting, the results of which express the destiny or favor of cosmic forces. One can see how the mythologizing of great combat heroes of a culture (aside from debates of historical accuracy) plays into the ritualistic practice of sport fighting itself. Westerners (and those other cultures) can become quite frustrated with for instance the 5th round dance-offs in Thailand's Muay Thai - and there definitely are many factors involved, including the role of gambling - but when the 5th round is seen in the much wider 1,000 year heritage of combat itself, where the killing of an opponent is not the aim, and wherein symbolized superiority becomes quite important, it makes much more sense that once dominance is established the fight is over. To put it in a very short form, bending back to the first observations about perishable housing: one is not life-and-death defending a homestead, willing to die for this territorial x without which you are nothing; one is engaged in a warfare of dominance on a fluid battlefield, within which retreat - with transportable wealth - might make very good tactical sense. And with this sense comes cultural value. The acceding to symbolic loss is much more readable in the context of SEA warfare. Much has been made of the fact that contemporary Muay Thai fighters fight very often, and from a young age. This frequency, some say, explains why dance-offs happen in 5th rounds in Thailand, fighters saving themselves for another fight which can be in 21 days. And there is much sense to this. But the roots to this persistent fighting/symbolic dominance likely go back to a veritable culture of constant warfare, endless skirmishes, but also one in which the death of the enemy is not the aim. A very high level of skill was developed across of lifetime through repetition and a culture of contest. Muay Thai is perhaps the most brutal of combat sports, with incredible moments of violence and very technical skill, but it is likely couched in a history that regarded battle itself quite differently than the West, a Southeast Asian perpetuity of fighting. Thailand of course is a very different place than Siam trading principalities of the 16th century, and its Muay Thai certainly has adopted many aggressive tendencies and tactics in its dialogue with the West and other cultures. Siam/Thailand has been a nexus of trade and international martial influence for a very long time, but there is a very important regard in which Thailand's Muay Thai is essentially Thai. It expresses something that feels deeply seated, manifesting both its Buddhistic culture, but also the foundations of the land itself. There is a significant measure in which the very high art of retreat and counter defensive styles which are coded into its scoring and passionate appreciation (including the narrative structure of gambling interest) speaks to a very logic of warfare that is not that of the West (or of the more globalized world). Its capture and control methods of combat borne out of near constant fighting going back hundreds if not thousands of years are essentially Thai, even though they produce confusion in many who come from a different logic of warfare developed out of different material conditions (land vs labor). If we change the very logic of Thailand's Muay Thai to fit a non-Buddhistic, kill-over-capture ethic for commercial reasons there is some sense in which we are radically changing, and even erasing Muay Thai itself, its very grace and meaning, and with it what it has to say about combat. I suspect that in some manner the absolute and real violence of Thailand's Muay Thai, its heightened brutality through elite skill display that many outside of the culture are drawn to actually comes from its capture-not-kill, agonistic (yet Buddhistic) cultural roots, in which retreat and counter fighting is prized. Many confuse that violence with aggression and the aim to end the other, and do not see its watery, transitory foundations. Edit in: I went back and read the original source for some of the most "not very bloody" accounts of Siamese battle, to get more context for them. Here is that source material, The Ship of Sulaiman, an Iranian report of the court of Ayutthaya in the last 17th century:1 point

-

Just finished the first part and I absolutely love this topic. I have a better understanding for what dominance is to Thai people and then fundamental difference of there perspective of warfare. The whole land vs labor is so eye opening and learning about how southeast Asia approached warfare is eye opening and just very interesting to me. The story about the French fighter in 1778 is pretty crazy and I love it. Thank you for sharing this, can't wait to finish reading1 point

-

Kathoey is not a Thailand-specific cultural identity, so you can use this word for yourself here without any problem. It's not the most polite word, but it is the most common word and speaking to your trainers and promoters, this is the word everyone will use. It is also how Trans folks here refer to themselves, outside of formal writing. I think your chances would be best for fighting up in the North, in Chiang Mai, as there are so many stadia, fights almost every night, and the levels are along a spectrum. There are a number of Kathoey fighters active right now up in the North, sometimes coming down to fight in Bangkok, but with good recognition and presence in the stadia of Chiang Mai. You could also go specifically to train with Nong Toom at her gym in Bangkok. That will absolutely provide a supportive training environment and Parinya (Nong Toom) will have the kinds of connections you'd need to fight, but the opportunities would likely be less frequent than in Chiang Mai. I also am catching myself as I'm saying this, because even though there are tons of fights in Chiang Mai and they won't be making a big deal about your gender, there is never any guarantee that opponents will be available for anyone all the time; it will depend on size and skill matching.1 point

-

Hallo Everybody I am planning a trip to Thailand in January for around 30 days full of Muay Thai. I could really use some guidance and advicer to make completely special from all of you. My plan is to do a private lesson in the morning and one in the afternoon. Is that good or a bad idea ?? My plan is to start in the northern Thailand with Ajahn Burklerk Pinsinchai in Lampang and train with him for 2 weeks. Ajahn Burklerk Pinsinchai Will you recommend rending a room nearby or is it possible to stay in his camp/gym??? There after to go to Bangkok and train with Namsaknoi, Yudthagarngamtorn in Sinha Mawynn Gym, Sagat Petchyindee, Samart- and Kongtoannee Payakaroon. Namsaknoi, Yudthagarngamtorn Is Namsaknoi doing or takes private lessons at his gym?? What is the best way to make at contact with Namsaknoi How much does a private lesson with Namsaknoi cost?? Sagat Petchyindee Is he still in 13 Coins Gym in Bangkok?? What is the best way to make at contact for private lessons with Sagat?? Samart- and Kongtoannee Payakaroon. What is the best way to make at contact with Kongtoranee and Samart Payakaroon email or Facebook?? I am there to learn the technical and cultural part of Muay Thai, and I would like to be very respectful to theses legends of Muay Thai who is teach me. To Sylvie and Kevin I am a long-time member of your Patreon and I have see all the videos. I use them as inspiration in my own training You are a Huge Source of Inspiration and a role model for many People. I cant not wait for the next video to come. Keep up the good work, All the best to You and Kevin All guidance and advicer will be gratefully received Thank You All Georg1 point

-

Thank you so much! Glad you are getting a lot out of the material. Your trip sounds fantastic, and you've picked some great mentors to train with. I don't know much about the private training situations, but I do think with Burklerk you should stay with whatever accommodations he has as Lampang can be spread out. And Sagat isn't at 13 Coins which closed a while ago. He trains privately in various gyms, often at Jaroenthong's gym in BKK. Sylvie helps book privates for him. I suggest contacting her through Instagram.1 point

-

It's awesome to hear you studying the fights of Chamuakpet. I haven't looked at them closely in a while so I couldn't say, but I like your idea that he's tracking the openside with his knee. Karuhat's switches seemed to be score relevant, closing the openside when he had the lead, etc.1 point

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.