-

Posts

2,273 -

Joined

-

Days Won

502

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

What many do not appreciate is that much of Thailand's traditional Muay Thai is really a Shield and Sword style of fighting, because of its inherent priority of defense. Offense largely is built off of the dexterous use of "shield". Entertainment Muay Thai is essentially turning to Muay Thai's Shield and Sword and saying: "Hey, fight without a Shield!"...but still make it "Muay Thai". You can't really. It's Shield and Sword.

-

Reading now on the idea that "technique", well, much more the focus on the machine of artistic development and expression, the focus on the craft of making, can be understood as a prelude to contemplation. Poet-engineer, poet-warrior, understood through German Romanticism, Novalis and Simondon. This is really the discovery of the meaning of aesthetic. Just beginning the essay though. (I suspect this is much of what Sylvie has been doing, and is the proper perspective to take toward "technique" which can become quite fetishized and worse, commodified, biomechanized in fighting. PDF posted below if anyone wants to read the article. Simondon_and_Novalis_Notes_for_a_Romanti.pdf

-

This story is about mastering energy, and focus on the few techniques that will bring it forward. The Unexpected. Sylvie put together her commentary on Fight 285. The fight is a beautiful example of two huge things that determine a fair number of fights: Energy and technique. One of the things that had a shaping impact on this fight was that when we travel like this, Ronin style, just quite far into rings that are on the outer edge of Thailand, far from the tourism Muay Thai, there is a wonderful kind of freedom from the politics of expectation, and by that I mean the sort of self-judgement that a fighter can bring in fear of disappointing others. In this fight it felt like we were traveling all the way to the Moon, ready to fight all renegade style (Sylvie in fact was booked to fight a Boxing fight back in Bangkok the next day, we would have to get in the car and drive all night to just make the Boxing fight with a few hours to spare, so just a tremendous old style adventure). But Yodkhunpon, who had never been to any of Sylvie's fights before, but had sparred with her pretty much daily for 5+ years, just shows up at the venue as we are ready to lay our mat down, unannounced. He's perfect and wonderful, but it was a huge deflation in that fight freedom and mission, with almost a depressive effect, at least as much as I could feel. It's like you went and climbed a far off mountain nobody climbs, and your best buddy is sitting there at the summit "Hey!" - totally unexpected, and even though great, completely antithetical to what you had mentally prepared for. We were ready for a marathon run of two fights, the greatest challenge of which wasn't the fights themselves - it was the tons and tons of driving, and lots of exhaustion - but suddenly it was a Pop Quiz on a single fight late in the night - Yodkhunpon had no idea Sylvie was fighting back in Bangkok the next afternoon. She wasn't running a 10K, she was running an Ultra that nobody knew about. The mission was: drive 8 hours into the night, sit several of hours on a mat, fight, drive 8 hours through the night back to Bangkok and get to a hotel maybe around 10 am, fight the Boxing fight around 2 pm, two fights in 26 hours 1000+ km of driving (it was an off coincidence that she had been double booked, and decided to honor it). She can fight like that back to back because she carries very little mental baggage with her when she does. It's just like a machine, a runner that gets into her cadence. She just puts her head down and fights free. So, it was a very difficult mental test record scratch. Suddenly the mind is not on the fight, or really more the long term mission, its on this unexpected change, a new focus. I could feel her deflation. I'm very sure that Yodkhunpon was just offering huge support, because fighting without entourage is a definite cultural no-no in Thailand, nobody does it, and it signals only weakness. But, this is the beauty of fighting so much. You discover these mental challenges that arise out of nothing. (Yodkhunpon also showed up unexpected on the mat laydown 2 fights later in Buriram at Fight 287, to every different effect, as Sylvie was already fighting under Therdkiat and was geared for that kind of relation.) Secondly, Sylvie's outside grabs just killed any momentum and intensity should could muster (fighting that unexpected deflation). Outside position means that you have to work immediately to try and get to a positive position, so you are never imposing yourself upon entry. This means running up hill to start every engagement in the clinch, a serious energy/momentum drain. The combination of the two of these, the emotional energy, the weaker technical entries (and the skill of the opponent) just made this a very steep grade to climb. Add in the cuts (which swung the score) and its an near impossible elevation. And in fact Sylvie's grit and experience gave her a great performance under those conditions. She pulled enough together that if there wasn't the cuts and the score swing she still was right there. On the other hand the cuts of course were a technical focus and achievement by her opponent, lifting her out of a battle into a open lane. So props. I do think that a different mindset, without the unexpected reversal of the mental landscape, would have made the difference here. Sylvie's an extremely experienced fighter who can ride through pretty much anything unexpected, and she rode through this, but it was an incredibly unusual event, two very rare things coming together. Your long time legend sparring partner shows up to corner you 500 km from where you expect he is, no word that's he's coming, for the first time ever appearing at a fight of yours...just as you are attempting a fight ultra that needs to be extremely streamlined emotionally. She did kind of fantastic in this equation, but took 7 stitches for it. But, the main focus of my commentary here more is the way that individual techniques and broad scale "energy" shapes connect up together to determine fights. The energy and tempo of a fighter can be undermined or amplified by small technical things. Inside grabs can become accelerants just when you need them to lift you. I also thought that Sylvie fought great in the 5th round. She minimized it because of fight context and that she had refused to chase the win, but she actually was out timing a timing fighter, and seemed to find some special internal rhythms that got her clicking...not for this fight, but for layers of future fights, something to tap into. Sometimes in a fight - especially in a career of hundreds of fights - where you have to explore a space, even if it doesn't serve victory just then and there. There is no replicating the ring, even in sparring.

-

A Battle of Affects I've argued that the highly Westernized (Globalized) affect expression in ONE and other Entertainment Muay Thai, typified in the Scream face you'll see in fight posters (which sometimes ironically looks like a yawn) and in post fight celebration, expressing aggro values that work against the traditional affects of Thailand's trad Muay Thai, a fighting art that comes out of Buddhistic culture largely organized around self-control...(that's a mouthful!) is attempting to invert Muay Thai's relationship to violence itself. It is interesting that spreading in the trad circuit is this mindfulness/meditative post-fight victory pose, an example of which is here, the young fighter with his trainer. This is no small thing because arguably culture is made up of prescriptions of "how you should feel", largely expressed in idealized body language and facial expression. When you change that prescription, in fact inverting, you are challenging the main messages of culture itself. One of the gifts of Thailand's traditional Muay Thai, I have discussed, is that it provides a different affectual understanding of violence itself, which then cashes out in simply more effective fighting in the ring. Something of a gift to a world that is more and more oriented toward rage and outrage.

-

This was all in answer to someone asking if learning Boxing would improve one's Muay Thai, my thoughts on that: Thailand's traditional Muay Thai was developed through a century-long dialogue with Western boxing - first through the influence of the British in the early 20th century, then the influence of American boxing in the mid-century. A great deal of this simply never "got into" Westernized versions of Muay Thai, mostly because it was exporting specific techniques, and was focused on all the ways Muay Thai was NOT like boxing. It has, historically, a lot of boxing reference and influence, at least in strains. This if further complicated by the fact that Boxing's influence on TODAY's Muay Thai in Thailand has dramatically dropped off. Arguably the deep fall in skill level (eyes, timing, defense, improvisation, variety of techniques, etc) across the board in Muay Thai among Thais can in part be laid at the loss of this past relationship. So yes, I would say training and maybe even more importantly fighting in Boxing probably gets you closer to the highest levels of Thailand's Muay Thai as it was in the its past (for instance the Golden Age 1980s-1990s). Aside from countless insight into technical aspects of the sport, footwork, a feeling for the control of distance and continuity, just being able to become comfortable in the pocket and defend yourself there will keep you from having to defend yourself by taking distance, a common "hack" of defense itself. But also..."training combos" isn't really what I would mean by "Boxing"...something some people mistake. It's almost the opposite of Boxing proper. [edit in for context: a look at the two top Muay Thai fighters in Thailand in the 1930s who also were top boxers in the SEA boxing circuit: What Was Early Modern Muay Thai Like? New Film Evidence (1936): Samarn Dilokvilas vs Somphong Vejasidh

-

The Deskilling of Muay Thai Through Combo-Fighting Discussing again the deskilling of Muay Thai in the ONE promotion (and to a lessor degree, other Entertainment forms of Muay Thai): To be quite broad about it ONE is just bite-down combo fighting turned into a sport so larger bodied, less-skilled farang can win endless pocket trading (which is seriously up regulated by bonuses and hidden penalties), so the (new, invented) sport can be promoted to non-Thais. It has nothing to do with the history of Muay Thai. It has to do with trying to create a product that will sell through Knockout highlights on Instagram. It also has almost nothing to do with Boxing. The impression it does is just the rather vast conflation thinking "combos" = Boxing. It, in my opinion, is contributing to the accelerated deskilling of the art and sport, rather than introducing important new skills, or returning it to past sophistication. Boxing is NOT "combos". 3 Zones of Fighting Here is a graphic to help explain: Over-simplistically there are 3 Zones of Fighting: ONE has effectively removed the importance of 2 of the 3 zones (because they take the most skill development, and Thais have been much better at those 2 down regulated zones). This is a deskilling of the sport: And, in the zone that remains (Zone 2), by removing defensive distance taking (the Thai emphasis on retreat and counter-fighting, and clinch, the traditional counter to a hands-heavy striker) they have made Zone 2 a haven for bite-down combo fighting (and NOT Boxing proper). That is to say, you can succeed by combo-ing through this zone, especially if you are larger bodied. On the other hand, if you look at the top graphic with all Three Zones, you can see how Boxing proficiency connects up, or fills in the high level development of zones 1 and 2 in Muay Thai. When all three Zones are in play bite-down comboing through the pocket doesn't actually do this, because it lacks the timing, vision and control over position that Muay Thai deploys in Zones 1 and 2. Boxing, on the other hand, because its so highly developed as a mid-distance art developed over centuries really, like Muay Thai, adds great complexity to the management of the 3 zones. A Historical Example: If you want to see what combo-ing does against a 3 Zone fighter the classic example would be Ramon Dekkers vs the 19 year old Sakmongkol: Sakmongkol simply refused to trade in Zone 2 and completely controlled Dekkers. ONE is basically the complete inversion of the Dekkers vs Sakmongkol fight. It removes Zones 1 & 3, and ostensibly would have forced Sakmongkol to trade with Dekkers, if we reimagine it. Eventually Sakmongkol, if he was forced to trade would have probably gotten caught...but not because Dekkers was a high level "boxer". It's because he combos through Zone 2, and the traditional control of that kind of fighter is dominating Zones 1 and 3. This is why Dekkers struggled when fighting Thais in Thailand, despite usually having a pronounced weight advantage. ONE is basically a "reversal" of the imagined injustice Dekkers losing to Sakmongkol and so many other Thais, changing all the rules to down regulate everything the Thais did better than anyone else in the world. But, this has nothing really to do with Boxing. Thailand was plentiful with Muay Thai fighters who were better actual Boxers than Ramon Dekkers. It has to do with the role of combo-fighting. asked to "define Boxing" (ie, its not "combo fighting): It's pretty hard to define a sport or art in a few sentences - or even paragraphs! - but what I would say is that Boxing has always been a sort of parallel in principle to Thailand's "Muay Thai", if you could somehow extract all the Boxing influence (which you can't). This is to say that "Muay Thai" excels at controlling the fighting space that lies outside of the boxing "pocket", through timing, the capacities of strikes to relate to each other at that increased distance (improvisationally), and very importantly, through defense. Boxing (abstracted) compliments this with a priority over the control of the space of the pocket, through the same. And, Muay Thai clinch then takes back over at the closest proximity, as a stand up grappling art (though Boxing too has its own lineages of very close-pressed fighting and even grappling). Training bite-down combos is really the opposite of all of this. It's just firing of memorized movement patterns and using them to blast or chop through the fight space. Combo fighting is not about controlling space at all, but rather dealing with the fact that you can't control it.

-

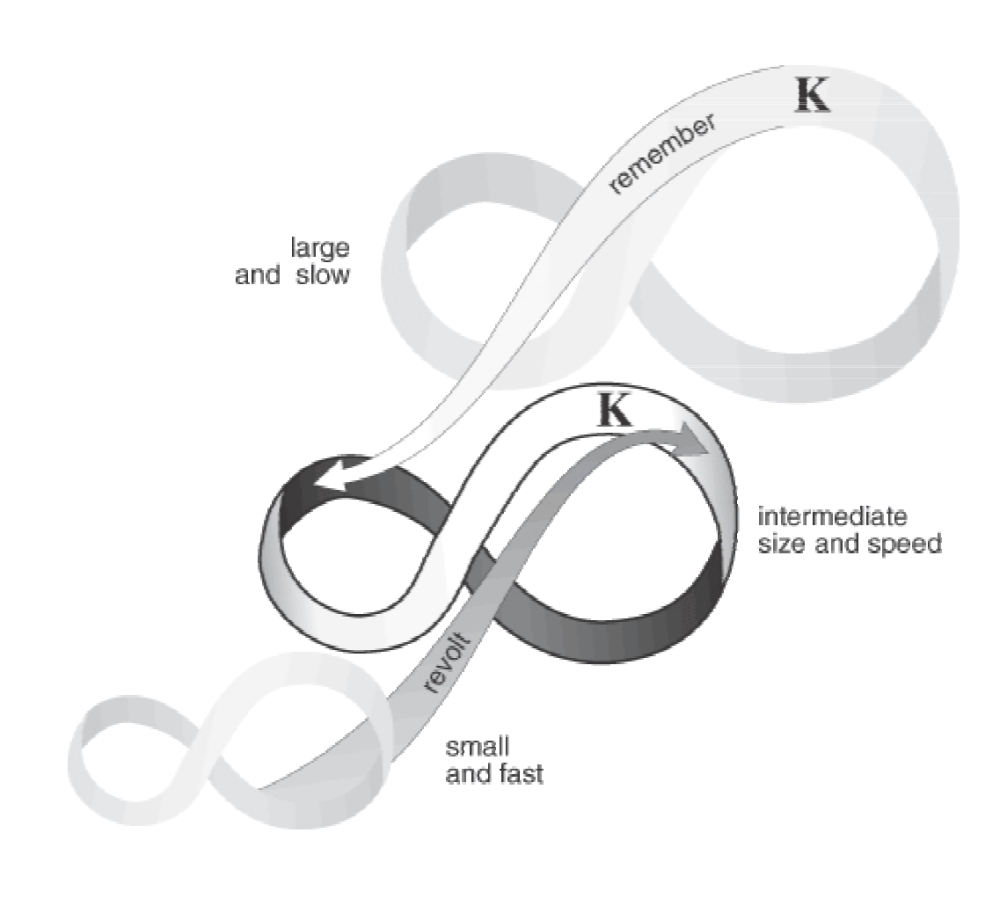

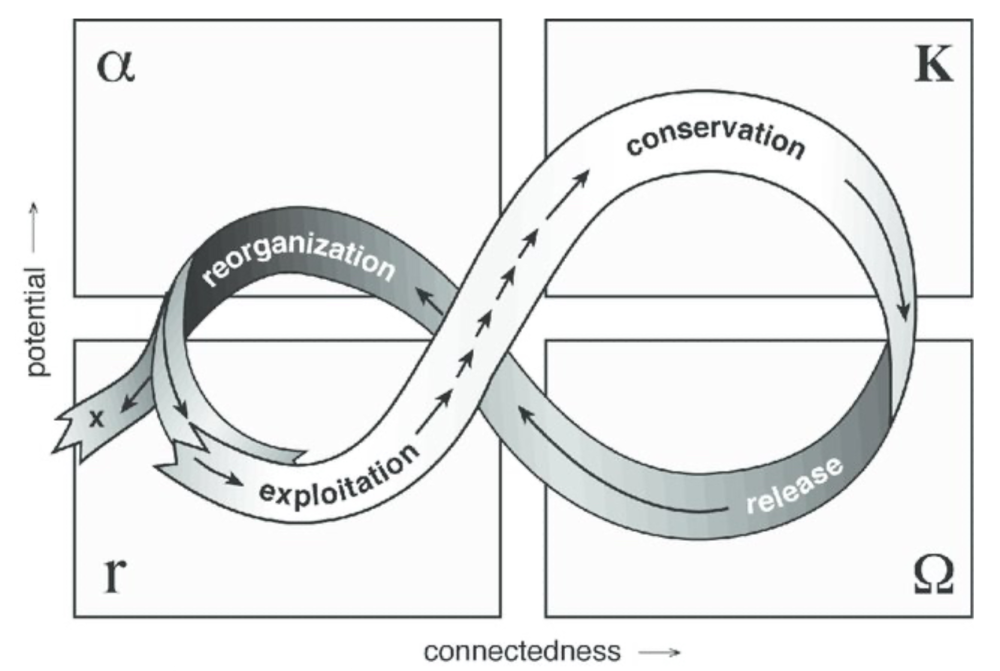

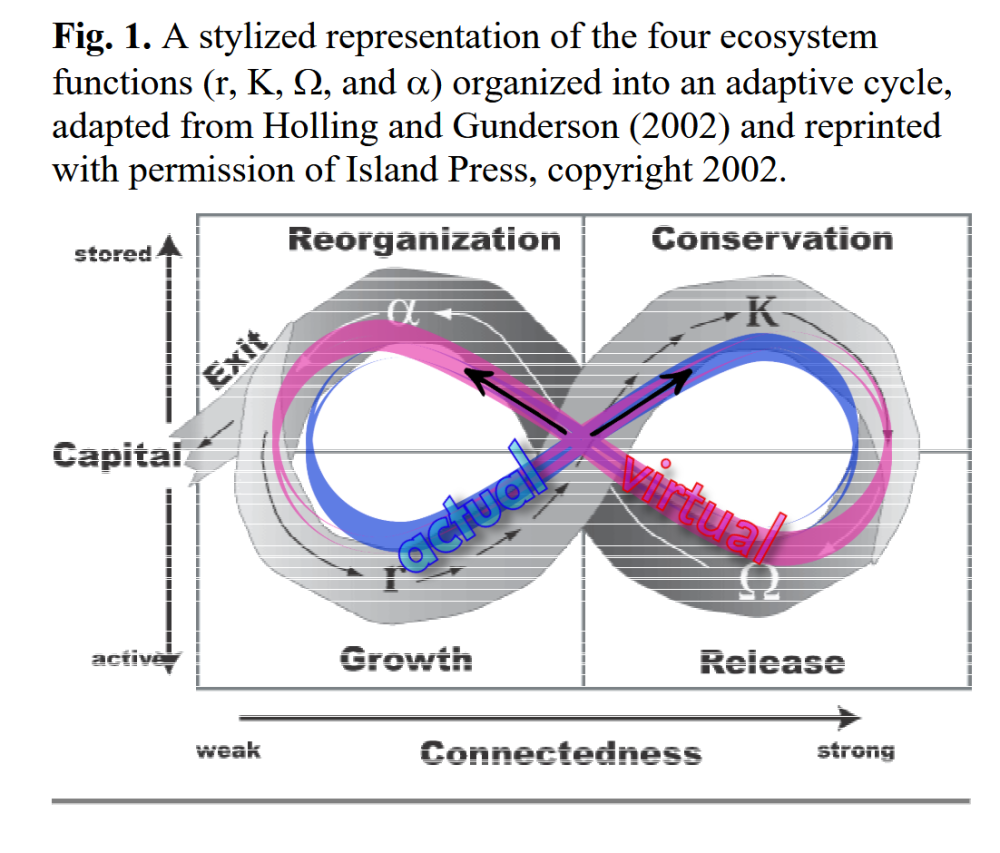

It is also notable that in this theory "colonization" occurs (expansion into vacated possibilities) as "reorganization" moves into "growth". This matches up somewhat with the colonization of Muay Thai by farang forces (including ONE and farang-focused Soft Power, an includes farang style gyms, and farang style training methods, farang fight promotion, etc), after a relative "collapse" of Muay Thai (release) through COVID lockdowns (and accusations). The "preservation" dimension, the recovery of past capacities, perceptions and know-hows, would occur through slower time scale adaptive cycles in this theory, because adaptive cycles are always nested.

-

Just a placeholding footnote here. I've been studying Panarchy Resilience Theory (one of the better articles attached) "Resilience of Past Landscapes: Resilience Theory, Society, and the Longue Durée" Author(s): Charles L. Redman and Ann P. Kinzig Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26271922 Resilience of Past Landscapes - Resilience Theory, Society, and the Longue Durée.pdf ...a theory first developed in the study and preservation of ecological systems, and then extended to archeology's study of the preservation and collapse of civilizations, in an attempt to formulate a stronger theoretically concept of the preservation (or just stabilization) of Thailand's Muay Thai. It argues that adaptive systems move in 4 phases, named here below: I've elaborated them overlaying other amenable philosophical terms and concepts. The aim is to build a concept in which conservation is only a phase, part in a series of adaptive responses, including phases of collapse.

-

To the above I would add, this is the enormous difference between transmitting the form of the ring sport, that is the living practices of (actual) training and (actual) fighting, including so much of its embedded social context...and simply trying to transmit its "techniques", as if a dead script of a forgotten language. The more we move towards the transmission of "techniques", the more we are heading towards the ossification (and likely ideologically, and unrealistically imbued "construction") of an art. Not "techniques".

-

Watched Surviving Bokator: A story of the attempt to preserve Cambodian Bokator, decimated by the Khmer Rouge genocide. Fascinating to see the generational challenge as the "Grand Master" (who had granted himself the status of "Gold" Grand Master having mastered "10,000 techniques") experienced the peel off of his young students who saw the future of the art with training foreigners. What is so striking is how fragmented and strained the "dignity" of the art is, hanging on the threads of only a few lineages, where recognition and opportunity arrives in only small islands of hope. When an art is NOT a living ring sport, when techniques become somewhat holy, somewhat calling-back re-enactments rather than living answers to resistant fighting, it puts the question of transmission into deep social conflict. And, throughout, quietly, you can feel the ideological component of a struggle against Thailand's Muay Thai as the Master often nonchalantly (and fairly unrealistically) defeats versions of neck grabbing, saying at one point "Why lose two hands?" (if I remember). I feel somewhat saddened to see a fighting art caricatured in this way, struggling for recognition but caught up in very real National identities, especially in a culture that went through a horrific genocide that sought to erase its past. I don't really want to review the film, other than to say that it's best moments were in the countryside where the rural teachers were, and with the kids, the students, idealistically and passionately committing themselves to the art. And...in a melancholy way, the revelation of the Grand Master's psychology, seeking to justify his life before a dead father who rejected the art. I wanted to learn something about Preservation itself, since we are always engaged with this, not only from how its is being done in other circumstances, but also to see how a film works to preserve. I can only say that it is a blessing that Thailand's Muay Thai is so very far from this state of fragmentation and forgetting...though understanding that Bokator is much more akin to perhaps Thailand's Muay Boran codifications.

-

This basketball commentary can EASILY be a primary insight into what is wrong with a lot of Muay Thai, and what set out the great Golden Age fighters of Thailand, from today. Everyone is "technique" training, trying to crib, drill and copy in Muay Thai. In kaimuay culture the higher level capacities of fighters were made through play, and fighting.

-

Honestly, I'm watching Karuhat reconstruct his movement heritage as he is gaining more capacity in his ACL'd up knee (3 weeks now maybe), and sometime shadows just the gesture of his right kick, lancing forward on his left, recovering knee, and he laughs,, because he knows that this little movement, this little lance, is like nobody else in the world. It's incredible. This micro movement, not even healthy, and he's already expressing in himself something nobody else can reach. and...he's standing in my livingroom.

-

I remember - I've probably written it somewhere else - driving to Phetjeejaa's family gym, which was up a few lanes and a dirt road, when she was the best female Muay Thai fighter in the world, at only 13 years of age, something we did everyday so Sylvie could train with her. And to get there we motorbiked up Khao Talo road, a pretty active road, and would pass by a Taekwondo studio with a large plate glass window showing the training mat inside, where numerous kids around Phetjeejaa's age all glowed in their starched white Gis, Ha-ai-ing in their moves. And I thought to myself...we are driving to where the best female fighter in the world trains and all these kids, the parents of these kids, don't even know she's there...up the road. And even if they did, they wouldn't train with her at her gym, because Muay Thai is low class, its dirty, nothing like the promise of a clean white Gi. The story of Muay Thai cannot be told without this strong division of class.

-

As Thailand's Muay Thai Turns Itself Toward the Westerner more and more, people are going to yearn for "authentic" Muay Thai This is one of the great ironic consequences of Thailand attempting to change its Muay Thai into a Western-oriented sport, not only changing the rules of its fights for them, and their presentation, but also changing the training, the very "form" of Muay Thai itself...this is going to increase the demand and desire for "authentic" Muay Thai. Yes, increasing numbers of people will be drawn to the made-for-me Muay Thai, because that's a wide-lane highway...but of those numbers a small subset is going to more intensely feel: Nope, that stuff is not for me. In this counterintuitive way, tourism and soft power which is radically altering Muay Thai, it also is creating a foreign desire for the very thing that is being altered and lost. The traveler, in the sense of the person who wants to get away from themselves, their culture, the things they already know, to find what is different than them, is going to be drawn to what hasn't been shaped for them. This is complicated though, because this is also linked to a romanticization, and exoticization sometimes which can be problematic, and because this then pushes the tourism (first as "adventure tourism") halo out further and further, eventually commodifying, altering more of what "isn't shaped for them". This is the great contradiction. There has to be interest and value in preserving what has been, but then if that interest is grown in the foreigner, this will lead to more alteration...especially if there is a power imbalance. So we walk a fine line in valuing that which is not-like-us. What is hopeful and interesting is that Thailand, and Siam before it, has spent centuries absorbing the shaping powers of foreign trade, even intense colonization, and its culture has developed great resistance to these constant interactions. It, and therefore Muay Thai itself, arguably has woven into itself the capacity to hold its character when when pressed. This is really what probably makes Thailand's Muay Thai so special, so unique in the world...the way it has survived as not only some kind of martial antecedent from centuries ago (under the influence of many international fighting influences), but also how it negotiated the full 100 years of "modernity" in the 20th century, including decades and decades in dialogue with Western Boxing (first from the British, then from America). The only really worrisome aspect of this latest colonization, if we can call it that, is that the imposing forces brought to Muay Thai through globalization are not those of a complex fighting art, developed through its own its own lineage in foreign lands. It's that mostly what is shaping Muay Thai now is a very pale version of itself, a Muay Thai that was imitated by the Japanese in the 1970s, in a new made up sport "Kickboxing", which bent back through Europe in the 1980s, and now is finding its way back to Thailand, fueled by Western and international interest. Thailand's Muay Thai is facing being shaped by a shadow of itself, an echo, a devolvment of skills and meaningfulness. On trusts though that it can absorb this and move on. some of the history of Japanese Kickboxing:

-

Wow, just watched an old Thai Fight replay of top tier female matchup that featured Kero's opponent in her last fight, someone she pretty much overwhelmed right away (with probably a 4 kg advantage). It was amazing to see the difference in performance on Thai Fight. Very skilled, very game, sharp. I came away realizing just how HARD it is to fight up. It changes everything. Sylvie takes 4 kg disadvantages all the time, and honestly overcomes them more often than not. What she does is so unappreciated, not only by others, but by Sylvie herself. Giving up significant weight and winning doesn't just take toughness, it takes an incredible amount of skill to keep that fighter away from what they want to do, to nullify all that size, strength and the angles. It's a complete art. You see this in female fighting all the time, big weight advantages REALLY matter.

-

I'm exploring two aspects of (seeming) spontaneous order (complexity) in Thailand's traditional Muay Thai. At the level of fights themselves there seem to have been a market dynamics in betting customs which drove diversity and escalating skill level, and within the traditional kaimuay there seems to have been an individuation process in training which also escalated skill level and diversity (or at least individualized expression), each of these with not a great deal of Top Down structuring, steering. I'm searching for the nexus between these two "self-organzing" dynamics, which may really be more complimentary, social systems.

-

Here is some private discussion traditional Muay Thai description which helped develop this parable of the Guitar. The challenge, from a philosphical sense, but also from an ethnographic sense, is to explain the diversity and sophistication of technique and style that arises in the Thai kaimuay, without much Top Down instruction. Here appealing to Simondon's theory of Individuation. But...in the Muay Thai (traditional) example, you actually are learning through a communal resonance with your peers, everyone else in the camp. Through a group memesis. It's not a direct relationship to the "music" per se, between you as an individual and an "experience" It's horizontal... how the person next to you is experiencing/expressing the music and relating to the authority and the work. I've compared it to syncing metronomes. youtu.be/Aaxw4zbULMs?... the communal form of the kaimuay (camp) brings together a communication of aesthetic, technical excellence, in which there is very little or NO top down direct control or shaping. young fighters sync up with the communal form, which actually also involves an incredible amount of diversity. Everyone kicking on a bag in a traditional setting has a DIFFERENT kick, because they haven't been "corrected" from the top down... But all the kicks in the gym have a kind of sync'd up quality, something that goes beyond a biomechanical consistency. There is a tremendous Virtual / Actual individuation dynamic that I think you would vibe on. This is what gives trad Muay Thai so much of its diversity. So much of its expression. It's because of its horizontal, communal learning through mimesis and a kind of perspective-ism If you go into a Western Muay Thai gym all the kicks on the bag, from all the students/fighters will be the SAME kick. With some doing it better or worse, with more "error" or less than others. In a trad Thai gym all the kicks are different. ...but, its hard to describe...because they all express some "inner" thing that holds them together. Maybe the same thing can be seen in other sports, like inner city basketball or favela football/soccer, things that have a kind of "organic" lineage. They hold together because they are a cultural form that is developed in horizontal context and comparisons with peers (not Top Down), but everyone has their own "game". It is very diverse. When people try to "export" knowledge from these, let's call them "organic", contexts, processes, not only are things "abstracted" (often biomechanically, traced into fixed patterns), but they are also exported with Top Down authority which channels and exacts "faithfullness" to some isolate quality. I think this is Deleuze's main issue with Platonism. The idea that there is a "form" and then "copies" which are more or less faithful. This, I'd argue, is actually something that prevails in "export" (outside of a developmental milieu), under conditions of abstraction (and perhaps exploitation). This is the "cut". 6:29 PM Here is a video where we slow motion filmed the kick of Karuhat, one of the greatest kickers in Thai history. We not only filmed him, but also Sylvie trying to learn through imitation. He is the only person who has this kick, in all its individuation. You cannot get this kick by just imitating it...(in person, Sylvie) or as a user practicing it from the video. It was developed in a virtuality of the kaimuay, by him. But, in documenting it...some (SOME!) aspects of it are transmitted forward. ...its a kick that is very different than many Western versions of the "Thai Kick" The keys to it are about a feeling, an affect array perhaps, and its uniqueness came out of the shared "metronome" of the traditional gym, the horizontal community of training, which also produced other kicks of the same "family of resemblance" (as Wittgenstein would say) Ultimately, its preservation is about returning to the instruction of a "feeling"...but also highlighting that the kick itself came out of a mutuality of feeling, and not a Top Down instruction. It's much closer to something like all the diversity of qualities of different pro surfers, who learned to surf not only one-to-one on individual waves, but in communities of surfers who would all go to one spot, and kind of cross-pollinate, compete in a mutuality (non-formally), steal and borrow from each other, a milieu. Not because there was some kind of Top Down authority of "how to surf" or "what exact techniques to use", or because there was an ideal "form" and a lot of error'd versions of it copying it. Almost everything that Sylvie produces is Sylvie learning through imitation and FAILING before the living example, because what we are actually documenting is not the Ideal vs the bad copy...but rather the actual, embodied, lived relationship that integrates oneself with another, converging in communication. She is "copying", but that's not really it. It's about syncing up, and the material/psychological relationship between two people, which smooths over the biomechanical "copy", and fills in some of the affects. But...this mutuality is really also artificial, because its one-to-one, and this isn't how Muay Thai technique is transmitted. It's developed in community. One-to-many. Many-to-one.

-

Balibar on Matheron, on Spinoza and Ego-altruism: Re-reading this essay, as well as many subsequent conversations involving Simondon's Pre-Individual Field (PI Field) theory of individuation, spurred me to write this Guitar parable explaining some of the developmental dynamics of the Muay Thai kaimuay today:

-

Imagine there is a guitar school, where boys come to live at a pre-teen age, that has something of a feel of a family. None of them know how to play a guitar. They are given guitars and given very basic drills to practice each day. They may be taught how to basically hold the guitar, or hold strings, but there isn't much technical instruction. They can see from older boys who have been at the school how it is done, and there is a lot of imitation. The drilling is fatiguing. Everyone drills together, playing scales or basic chord series over and over, and everyone is doing it together. They can see each other, and even the most experienced players in the school are sitting with the most inexperienced. Some may struggle, they push through. There is a strong sense of obligation, and the dynamics of the group hold everything together. Sometimes this drilling is grueling. Experienced student players are so adept at the drills they can do them in a very lazy fashion, or they can do them with flair and personal small variation. Sometimes they can find themselves "competing" with others in the group, just in a sort of expressiveness, because the drills are so boring. The fatigue units everyone. Younger boys watch the older boys add small qualities to their drills. Aside from drilling like this, there battling. This is almost always quite playful...though there is always a dimension of dominance, of agonism. In pairs students "battle each other" in back and forth exchanges of aspects of music, much of it drawn from the skills in the drills, but the battles are musical, and expressive. Communally there develops an aesthetic where one knows if they are losing a battle at any point, mostly from watching the playful battles of older guitar students. The younger students battle in a rather simplistic way. There is a kind of metronome of music as everyone is battling at the same time. There is almost no "instruction" given in these battles, no correction. In the drills there may be some correction, but the correction is toward the intensity and focus given. Most of the correction comes organically from the group, and the lead examples of developed players. Because fatigue is involved in these sessions, playful guitar battles, which last in rounds everyone follows, may by quite lowkey. Students that know each other well may just used them to rest, in only a gentle back and forth, together "mock" battling. And then other playful battles may really escalate, because social hierarchy in the school, where everyone lives together, is always contested. Winning at any one time feels substantive. So, in these sessions of fatiguing drilling together (drills which develop personally expressiveness, and extraordinary endurance) and playful battles (which vary in intensity from sleepwalking imitative back and forth, to outright contests of superiority, and sometimes passing between the two intensities in alternation), make up the conditions for skill development, not only at the technical level, but also the level of styles. At a fairly young age the students of the school also participate in public guitar battles versus other guitar students of their own approximate skill...as do the more experienced students. Everyone attends these, and guitarists in these battles win money, some of it for themselves, some for the families they don't live with, some for the school. Gambling abounds in these public battles, so guitarists on stage can always tell if the battle is close, who is winning, from audience bets and their shouts and energies. The battles have a strong aesthetic shape, composed of 5 rounds. In the aesthetics of music, as the battle builds the most intense back and forths occur in rounds 3 and 4, when the music is really building. Wins and losses in these public battles raise or lower the social standing of the students when they go back to the home school. And the display of creative skills in play is fed back into their play battles and drilling back in school. Sometimes they are corrected, often they are urged to be more of a certain way, a way they would have won, but there is a cycling dynamic between the public battles, and the playful battles back in the school. Everyone in the school is watching everyone. Student learn from imitating the better, older, more developed students, but also from others that are their own peers. Because everyone of a certain age and experience is sharing the fatigue, and the struggle, how others your age are doing things affects and inspires you. The environment is incredibly mimetic. Identities and skills are developed in the context of others. The host of schools in a region, and their 100s of local public battles, collectively create the styles of the music of that region. Certain techniques or tempos fall out of favor, others rise, according to the gambling values. Much of this is shaped by the underlying culture, and the cumulative history of the music, generations of public battles, and even famous musicians that grew out of these battles. It is an agonistic aesthetics of music, full of styles and localized techniques that have developed in diversity, but it holds together as a single "music". If you hear this music being played, you recognize it right away.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

.thumb.png.5f06d27e0aa911e17d9e746c91a86aec.png)

.thumb.png.d5943433772f13869fbd7a45b2531809.png)