-

Posts

2,265 -

Joined

-

Days Won

501

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

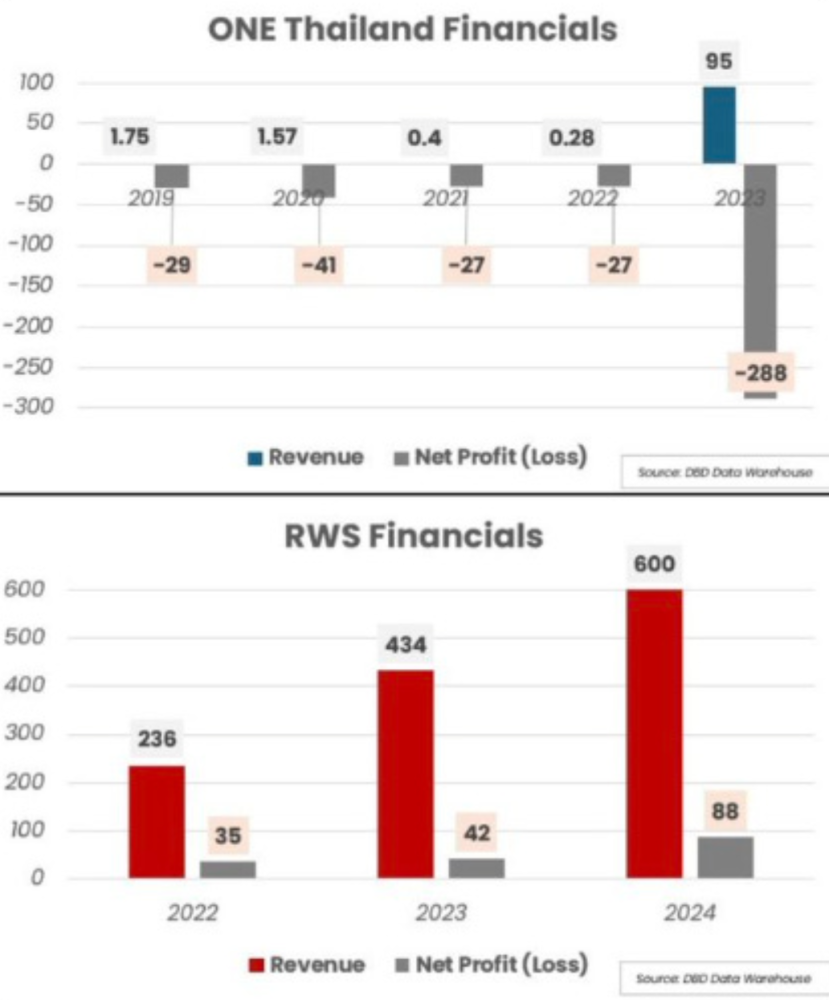

I thing that many people miss in assessing ONE's future, or even capacity to do anything, is that almost everything you know about ONE (aside from financial declartive documents, and the few voices that escape NDAs and non-disparagement agreements), has been told to you by ONE. So every concept of "reach" or success that is measurable or on a scale comes from the ONE picture building. And...its a bit like asking Trump how his Casinos and buildings are doing. A good, if small, example of this is how RWS is far exceeding ONE Thailand in revenue, by a factor of about 6. source It just shows a very different concept of business. RWS actually wants to generate revenue at the gate, ONE much rather would pack houses with loads of given away tickets and project massive success through its social media agreements and message control. ONE is trying to generate (one might even say "fake") the feeling of a massive moment...because everything is basically a commercial for the next investor round. They much less want actual fans, so much as the vast impression of fans, and spending everything they can to create the impression is a priority...because the "real" revenue" is a massive investment round, unfortunately something that seems to be drying up. They aren't selling the sport to fans, they are selling it to investors. Sizzle, not steak. So any kind of picture we draw from is already part of this enormous Image creation, which it was hoped would bootstrap itself through dramatic gestures of largess. Flaunting huge payment numbers, etc. A form of "Mystery"... Which isn't to say that none of this is good. The world, and especially the "good" of Capitalism, is made from ostentatious pretension. There is in the world the whole "escape velocity" theory, the fake it until you make it, and when fueled by more than half a billion dollars there is a lot one can fake, in fact the faking becomes quite real, affects real lives, turns into power, creating new capacities and opportunities. So, one of the most compelling questions about what comes now is that the actual question of revenue and profit making, peeled away from the presentation of profit-making, gets put up against other forms of Thailand Muay Thai that are pulling revenue. And, because so much of what has come to us has come through the filter of ONE's image making its very hard to know where anything is at all. Everything is bigger, better, about to break through. It's the Golden Rule of Trump-like positive image driving, which when looking at the world does lead to power itself. Invest now! Buy now! You don't want to miss out on this once in a lifetime opportunity! A certain kind of power. We of course should not be lead astray into thinking that Thailand's Muay Thai does not develop and express itself through all kinds of power relations, many of them institutional, many strongly divided by class differences and entrenched hierarchies, There is no "innocent" Muay Thai in the sense of a Muay Thai without efforts of domination and control, in fact the art and sport arguably is the ritualized performance of such. It's more though that maybe this form of economic magical portrayal, as it is so globalized, so hyperstated, so flowing from that which is outside and beyond Thailand, feels like it could be destructive. Too much sizzle...too little steak?

-

This is my wild guess about the possible future of ONE with the rumored loss of both big investors and Amazon Prime: My take...I suspect it will morph into a significantly contracted phase that is something the Thai gov will support as part of its Soft Power commitments which will somewhat balance out the loss of big investors. There may even be rule changes to bend a bit closer to trad elements (maybe glove changes? maybe a touch more clinch?); guessing there will be a significant downgrade of top end pay and bonus rates, and probably significant cuts into the all-important marketing budget too. It will fall more in line with Entertainment offerings like Thai Fight and RWS. The challenge is the struggle over the shrinking Thai talent pool, which is also no longer producing transcendent talents like Superlek and Nong-O, and how it will compete against other Entertainment promotions without big top end pay and bonuses (I believe RWS revenues were reported as much as 6x ONE's in Thailand). It may have difficulty continuing to snipe the high level names produced by other promotions. It still has a well-built-out, massive digital media footprint in a very small info ecosystem and that proven strategy, and has secured a place in the Thai combat sport imagination, two very big assets.

-

It's pretty amazing that ONE has under contract the woman who at least as an argument for being the greatest female Muay Thai fighter of all time -- but hasn't fought a "real" full rules Muay Thai fight for maybe 7 years now -- and they don't even have her fighting their version of "Muay Thai", or have her face their own very qualified female Muay Thai champion...who is having trouble finding opponents. Phetjee Jaa was a VERY good, multi-skilled, every distance Muay Thai fighter before she became an amateur boxer, and then an Entertainment Thai Fight fighter...now in the service of Kickboxing. Properly, Phetjee Jaa should be representing female Muay Thai to the world. It was her true art, that which she was raised in...until she ran out of opponents. Female Muay Thai has historically missed out through her absence. She's not really a Kickboxer, though she can handle the sport and ruleset. She's a Muay Thai fighter.

-

Was thinking about a commenter telling another redittor that they were "elitist" for not liking ONE FC, and preferring trad Muay Thai, the absolute irony of them thinking that a new globalized version of the traditional form of the sport (a sport which has been practiced and fought by the working poor throughout Thailand for at least a century, in some ways MADE by the rural nakmuay), a new commodity version which has been invented by hi-so wealthy, "elite" Thais, wealthy sons who went to school in very expensive schools in the United States, a new sport modeled in the Thai high-brow love of MMA (MMA is a Thai hi-so taste in Thailand, because originally you needed a satellite dish to watch it, so only rich young people watched it back in the day), so completely born of Thai elite taste making, and then funded massively, to the tune of more than a Half a BILLION dollars, by wealthy Arab investment and other very elite Venture Capital investment groups, some of the most powerful investment sources in the world...all of that, absolutely about as elitist as you can get, reinventing the traditional sport, inverting pretty much all of its values, in the image of wealth itself, so that affluent tourists and consumers will buy it...but, if you don't like it...you are elitist. The whole thing is about as posh as you can get.

-

I think people don't even understand what it was that ONE did. It had almost nothing to do with small gloves, or rulesets or aggression or any of that. It bought up the most developed Thai talent (which was quite cheap, and many past prime) and then poured massive amounts of marketing dollars into taking over comms, and absolutely controlling messaging in very small information ecosystems, squeezing out almost all other content...and used this to create a constant "commercial" of how massive a success it was. They could have done comm control with a totally different combat sport product and have had the very same, if not even better success. It was about manufactured digital footprint. So when Entertainment Muay Thai tries to model itself on ONE promotional rulesets and styles its actually copying the wrong thing. There is some benefit to mirroring the style and ethos that ONE already seeded the ecosystems with, because all that groundwork has been done, and it changed consumption...but it actually wasn't all the aggression, or the scoring kind or even the knockouts. It was much much more about the sizzle and not much to do about the steak. Its actually the systematic control over messaging, from SEO link farming and story planting, to buying up social media sharing circles and influencers, all the narrative shaping. Traditional Muay Thai as a product is probably even MORE amenable as a product than the made up sport that ONE created. It has massive valuation in terms of depth of complexity (deeper retention investment), historical material (narratives to be driven), and overall skill level. Trad Muay Thai as it bent toward Entertainment versions has copied the wrong thing.

-

from the same article above, this is one of the primary confusions about traditional Muay Thai...it is not primarily "labor". As Stiegler conditions the difference it is "work" as it involves the "techniques of the self and others" and leads to the "trans-formatio of oneself" and others. In this sense it is vital as a form of work in the field of potential violence.

-

Why the preservation of traditional Muay Thai, its kaimuay origins and socio-cultural knowledge especially as it relates to violence and the affects matter...diversity of knowledge matters: Only by understanding work in this way can we identify the exosomatic innovations (whether technical or technological) actually required by and compatible with a desirable future for a locality …. This is the work of noesis, that is, of thinking, in all its forms, and as practical as well as theoretical, familial, artisanal, sporting and artistic knowledge, and thus theoretical, juridical and spiritual knowledge in the broadest sense. This belongs to what we therefore call noodiversity and noodiversification. - Stiegler Technophany_Entropies_V3N1_AA.pdf

-

Some of my thoughts on the weigh-in change, and how it reflects back onto deeper aspects of how Thailand's Muay Thai is fought, in this Reddit thread: Recently announced. This should produce much bigger weight differences in the ring, move towards even more power and forward aggression combination fighting, and the diminishment of skilled (femeu) fighting (the longtime hallmark of Thailand's art and sport), and should favor farang who are larger bodied and often more versed in Western style day-before, deeper cut weight drops. It also seems like it will put a greater burden on small kaimuay and provincial fighters, as they would have to come to Bangkok the day before a fight, increasing fight expenses when often its hard to even break even on fights (perhaps there will be some support?). For the longest time day-of weigh-ins were the standard of legit matchup Thai trad fighting. Silently this change could have long lasting effects. and As I mention above (here) there are some aspects about Thai traditional scoring that also keep deep weight cutting in check (these are things people are also trying to change to a more Western style). Thais can cut the way that they do, same day, in part because of how the sport is fought and judged. You just can't cut too deep and still win. Also, Thai trad weight cutting is very different. It's not about making huge plunges close to the fight. It's incrementally getting closer to the weight, with its own science and knowledge. and It's a National PAT (SAT) rule change. It's supposed to cover all Muay Thai, part of a "Grassroots to International" effort. Entertainment Muay Thai was already headed there, or there, so this most dramatically effects traditional stadium Muay Thai in Bangkok I imagine, and major trad promotions. Enforcement of rules in Thailand is quite varied, so I imagine it pragmatically has little to do with trad fighting in the provinces (?) unless a part of the new gov outreach there. (just guessing). Have no idea what it means for fighting in tourist centers like Phuket or Chiang Mai. and Some of deep weight cutting was constrained by two things in trad day-of fighting. The first was because you were fighting later that day you were really limited in how far you could effectively go...but the second hidden aspect is that because trad scoring aesthetics have of a lot of subtle by important aspects to them (ie, they aren't entirely about "points" or "damage" but involve things like "ruup" [posture] and balance), you couldn't really go into the ring very depleted...your ruup and just your substance as a fighter would be down-scored. This was even more reinforced by Thai narrative scoring aesthetics (which a lot of Westerners get upset about). If you FADE in a fight you are penalized, because the fight has an arc to it. You have to be strong in round 4 or you just won't win. This, combined with the same day weigh-in, created a natural barrier for how low you could go. You have to have stamina. You can't artificially pad your lead with early rounds point wins, and coast in the 4th. One of things people don't realize is that if you chop away at the narrative scoring structure (the new rules start heading in this direction), and at trad scoring aesthetics AND add deeper weight cuts, this produces a huge swing which could be dangerous. They are mixing Thai and Western protocols and also Thai and Western fighting aesthetics in ways that I think haven't been completely thought about. Thai practices developed over many decades within their own sport. and Longtime Thais have a very precise understanding of how to cut weight in the trad scene, day-of weigh-in, trad scoring aesthetics. Western weight cutting, and weight cutting competition trends will start to seep in. This is pretty dangerous in my view, because knowledge of how to do the deeper cuts will communicate itself very unevenly. Already there is a lot of pseudo "Sports Science" stuff floating around Thailand, often via lightly qualified farang who offer themselves as advisors or coaches. Lots of Thais will end up having partial or just plain mis- information about how to cut in a Western fashion. Add in the common use of diuretics which amplifies issues. The Western cut is very different than the Thai cut. And mixing the two, or moving back and forth between them could be dangerous. Doing a Thai cut with a Water loading cut or a sodium loading cut, or deep Albolene sweat, who knows what can happen. At least IVs (which are very popular in Thailand) are plentiful, but still, there is danger here. Once pieces of information start entering the culture they can become a game of telephone. Spread this out over an entire sport and its asking for risks. and I suspect that one of the main reasons for this is actually economic...that is as Thailand's labor pool for fighters shrinks its harder to fill the many cards. This rule change means that a wider group of fighters are available for any particular match. Matchmakers are less constrained. Also, it happens to serve folding larger-bodied Westerners into the trad market...ie, they can fight much smaller Thais. This helps with the labor market some (more fighters to choose from), and also helps with Soft Power (selling the sport abroad). More Westerners fighting, and more Western winners (probably more Westerner belt holders as well). It really addresses in the short term several pragmatic issues, and it seems like its a government ambition to kind of codify all of Muay Thai, so that it can export the sport more readily, which is unfortunate because much of the sport's uniqueness and ultimate marketability in a deeper sense, relies on its uncodified, un-rationalized nature. I also am not sure if it just leads to everyone then using the same weight cutting practices, as for instance happens in Internationalized sports, because as I have mentioned in other comments, Thai cuts are very different than Western cuts, and the way that knowledge and practices disseminate in Thailand really is uneven. It's much more likely that Westerners will just hold a significant advantage, as will big Westernized or Western-informed Thai gyms (who already have large political advantages in the sport), and the smaller gyms and provincial fighters will not be able to play the same weight cutting game, and may even be led into dangerous hybrid or misinformed practices.

-

Well, the PAT announced 24-30 hr weigh-in, a huge change the sport. Get ready for tons of weight bullying (including bigger farang fighting small Thais in trad stadium fights). Basically for all practical reasons all weight classes have been expanded. This is in part in relationship to the labor crisis mentioned above, the capacity to draw from a wider range of fighters to fill cards. Trad Muay Thai will likely have greater skill disparities (shrinking talent pools) and now more massive size differences, as well as drawing in more farang who will become part of this solution. This will also likely mean more farang stadium/promotion belts in trad fighting. Of course laws in Thailand are unevenly forced, so there could be major hiccups in implementation, including a significant problem that fighters now have to come to Bangkok the day before, which means even greater costs to fight...which could ALSO shrink the fighter pool. Already many gyms, small kaimuay, have difficulty even breaking even in Bangkok fighting expenses. Will outlying fighters be able to regularly afford to come to fight in Bangkok, especially in a scene that favors the political power of major Bangkok gyms (they can't dependably recoup their expense by betting on their fighters). These changes could have a massive stylistic impact on Thailand's trad Muay Thai over time, as it gives even more advantage to size and power. Saenchai was famous for his criticism of the loss of femeu fighting after he left the trad stadium scene, because large-bodied power clinch fighters (who he had some trouble with) had become the gambler's favorite. With the even greater increase in size differential now, and the influence of more smashing and clashing fighting styles of Entertainment Muay Thai, it stands to reason that power will become even more effective over femeu skill than ever before. In the Golden Age there were fairly substantial size differences, but the technical skill level of fighters was such - and the trad artful scoring bias in favor of - that small fighters like Karuhat and many others could handle 2 or more weight class (in the ring) differences. This high level of the art just really is missing in this era, and scoring biases are shifting toward the power aesthetic. Trad Muay Thai may become much more combo-heavy smashy with the big man coming out on top.

-

Some notes on the predividual (from Simondon), from a side conversation I've been having, specifically about how Philosophies of Immanence, because they tend to flatten causation, have lost the sense of debt or respect to that which has made you. One of the interesting questions in the ethical dimension, once we move away from representationalist thinking, is our relationship to causation. In Spinoza there is a certain implicit reverence for that to which you are immanent to. That which gave "birth" to you and your individuation. The "crystal" would be reverent to the superstaturated solution and the germ (and I guess, the beaker). This is an ancient thought. Once we introduce concepts of novelness, and its valorization, along with notions of various breaks and revolutions, this sense of reverence is diminished, if not outright eliminated. "I" (or whatever superject of what I am doing) am novel, I break from from that which I come from. Every "new" thing is a revolution, of a kind. No longer is a new thing an expression of its preindividual, in the ethical/moral sense. Sometimes there are turns, like in DnG, where there is a sort of vitalism of a sacred. I'm not an expression of a particular preindividual, but rather an expression of Becoming..a becoming that is forever being held back by what has already become. And perhaps there is some value in this spiritualization. It's in Hegel for sure. But, what is missing, I believe, is the respect for one's actual preindividual, the very things that materially and historically made "you" (however qualified)... I think this is where Spinoza's concept of immanent cause and its ethical traction is really interesting. Yes, he forever seems to be reaching beyond his moment in history into an Eternity, but because we are always coming out of something, expressing something, we have a certain debt to that. Concepts of revolution or valorized novelty really undercut this notion of debt, which is a very old human concept which probably has animated much of human culture. And, you can see this notion of immanent debt in Ecological thought. It still is there. The ecosystem is what gave birth to you, you have debt to it. Of course we have this sense with children and parents, echo'd there. But...as Deleuze (and maybe Simondon?) flatten out causation, the crystal just comes out of metastable soup. It is standing there sui generis. It is forever in folds of becoming and assemblages, to be sure, but I think the sense of hierarchy and debt becomes obscured. We are "progressing" from the "primitive". This may be a good thing, but I suspect that its not. I do appreciate how you focus on that you cannot just presume the "individual", and that this points to the preindividual. Yes...but is there not a hierarchy of the preindividual that has been effaced, the loss of an ethos. I think we get something of this in the notion of the mute and the dumb preindividual, which culminates in the human, thinking, speaking, acting individuation. A certain teleology that is somehow complicit, even in non-teleological pictures. I think this all can boil down to one question: Do we have debt to what we come from? ...and, if so, what is the nature of that debt? I think Philosophies of Immanence kind of struggle with this question, because they have reframed. ...and some of this is the Cult of the New. 3:01 PM Today at 4:56 AM Hmmmm yeah. Important to be in the middle ground here I suspect. Enabled by the past, not determined by it. Of course inheritance is rather a big deal in evolutionary thought - the bequest of the lineage, as I often put it. This can be overdone, just as a sense of Progress in evolution can be overdone - sometimes we need to escape our past, sometimes we need to recover it, revere it, re-present it. As always, things must be nuanced, the middle ground must be occupied. 4:56 AM Yes...but I think there is a sense of debt, or possibly reverence, that is missing. You can have a sense of debt or reverence and NOT be reactive, and bring change. Just as a Native American Indian can have reverence for a deer he kills, a debt. You can kill your past, what you have come from, what you are an expression of...but, in a deep way. Instead "progress" is seen as breaking from, erasing, denying. Radical departure. The very concept of "the new" holds this. this sense of rupture. And pictures of "Becoming" are often pictures of constant rupture. new, new, new, new, new, new... ...with obvious parallels in commodification, iterations of the iphone, etc. In my view, this means that the debt to the preindividual should be substantive. And the art of creating individuation means the art of creating preindividuals. DnG get some of this with their concept of the BwOs. They are creating a preindividual. But the sense of debt is really missing from almost all Immanence Philosophy. The preindividual becomes something like "soup" or intensities, or molecular bouncings. Nothing really that you would have debt to. 12:54 PM Fantasies of rupture and "new" are exactly what bring the shadow in its various avatars with you, unconsciously. This lack of respect or debt to the preindividual also has vast consequences for some of Simondon's own imaginations. He pictures "trade" or "craft" knowledge as that of a childhood of a kind, and is quite good in this. And...he imagines that it can become synthesized with his abstracted "encyclopedic" knowledge (Hegel, again)...but this would only work, he adds, if the child is added back in...because the child (and childhood apprenticeships) were core to the original craft knowledge. But...you can't just "add children" to the new synthesis, because what made craft knowledge so deep and intense was the very predindividual that created it (the entire social matrix, of Smithing, or hunting, or shepherding)...if you have altered that social matrix, that "preindividual" for knowledge, you have radically altered what can even be known...even though you have supplemented with abstract encyclopedic knowledge. This is something that Muay Thai faces today. The "preindividual" has been lost, and no amount of abstraction, and no about of "teaching children" (without the original preindividual) will result in the same capacities. In short, there is no "progressive" escalation of knowledge. Now, not everything more many things are like a fighting art, Muay Thai...but, the absence of the respect and debt to preindividuality still shows itself across knowledge. There are trends of course trying to harness creativity, many of which amount to kind of trying to workshop preindividuality, horizontal buisness plan and build structures, ways of setting up desks or lounge chairs, its endless. But...you can't really "engineer" knowledge in this way...at least not in the way that you are intending to. The preindividual comes out of the culture in an organic way, when we are attending to the kinds of deeper knowledge efficacies we sometimes reach for.

-

"He who does not know how to read only sees the differences. For him who knows how to read, it all comes to the same thing, since the sentence is identical. Whoever has finished his apprenticeship recognizes things and events, everywhere and always, as vibrations of the same divine and infinitel sweet word. This does not mean that he will not suffer Pain is the color of certain events. When a man who can and a man who cannot read look at a sentence written in red ink, they both see the same red color, but this color is not so important for the one as for the other." A beautiful analogy by Simone Weil (Waiting for God), which especially in the last sentence communicates how hard it is to discuss Muay Thai with those who don't know how to "read" its sentences. Yes, I see the effort. Yes, I see the power. Yes, I even see the "technique"...but this is like talking about the color of sentences written out at times.

-

from Reddit discussing shin pain and toughening of the shins: There are several factors, and people create theories on this based on pictures of Muay Thai, but honestly from my wife's direct experience they go some what numb and hard from lots of kicking bags and pads, and fighting (in Thailand some bags could get quite hard, almost cement like in places). Within a year in Thailand Sylvie was fighting every 10 or 12 days and it really was not a problem, seldom feeling much pain, especially if you treat them properly after damage, like this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ztzTmHfae-k and then more advanced, like this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mcWtd00U7oQ And they keep getting harder. After a few years or so Sylvie felt like she would win any shin clash in any fight, they just became incredible hard. In this video she is talking about 2 years in about how and why she thought her shins had gotten so hard: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFXCmZVXeGE she shows in the vid how her shins became kind of permanently serrated, with divots and dings. As she discusses only 2 years in (now she's 13 years of fighting in) very experienced Thais have incredibly hard shins, like iron. Yes, there are ideas about fighting hard or not, but that really isn't the determining factor from our experience with Sylvie coming up on 300 fights and being around a lot of old fighters. They just can get incredibly tough. The cycles of damage and repair just really change the shin (people in the internet like to talk about microfractures and whatnot). Over time Sylvie eventually didn't really need the heat treatment anymore after fights, now she seldom uses it. She's even has several times in the last couple of years split her skin open on checks without even feeling much contact. Just looked down and there was blood.

-

The race for cheaper "grassroots" labor to fill Entertainment Muay Thai cards is on. Rajadamnern vs Lumpinee, trad Muay Thai vs Entertainment Muay Thai. This is the next economic challenge for the sport. Who can tap the rural fighter labor source better, as the trad festival fight culture that has feed the sport for over a century is quickly eroding.

-

Heard backstage at a trad promotion in Bangkok, Dieselnoi loudly complaining that Thais don't know how to knee anymore, nobody even knees to hurt. Just kneeing for show and points. *This isn't a question of intensity (how hard), its one of technique, and continuity. The knee techniques of Hapalang gym have just been largely lost.

-

What many do not realize is that ONE has so thoroughly commandeered the social media ecosystem of Muay Thai in Thailand (quite consciously, as part of its marketing approach, absorbing trad social media accounts, controlling messaging across all platforms through various systematically means...and quite brilliantly I would say), that many, many New Gen Muay Thai fans in Thailand, who speak no English at all, now have bought 100% into the ONE Entertainment full power smash aesthetic. Demographically much of it is somewhat a new fan base for Muay Thai, but its very vocal in SoMe post comments, and has influenced the older online gen as well. What we in the West are drawn to in traditional Muay Thai is now is ardently being pushed against by a segment of Thai fandom now, even in the trad ruleset. There is a kind of tug-of-war now between the traditional values of superior fighting and the new International smash values, and hybrid promotions like RWS are kind of caught right in the middle, but seemingly for now siding with trad values for the most part. It does mean though that some trad fighters are just going to go in there and smash on trad cards, which is kind of amazing because this change has occurred in only a few short years.

-

Sylvie faced an undersized opponent yesterday in a Boxing match, beyond her control, so on the way home we counted up the number of times in her 280 plus times she's faced someone smaller than her, and it is now 6. And each time it was a no contest bad match. Size differences do really matter. Firstly, it is absolute remarkable that Sylvie's only faced 6 opponents smaller than her, this is a just a very common and in fact pretty pursued advantage for Westerners. Some Westerners are in fact hard to match because they are big, but also gyms that represent Westerners also leverage for size advantage as well. This is something Sylvie just never has engaged in, its an advantage she NEVER wants...in part because she knows what its like to be the smaller fighter, having fought vastly up for most of her career. (This is one reason, among many, that Sylvie has never hooked herself up to a powerful gym or promoter trying to advance her, its the form of the sport to try and find and push for as many advantages as possible in Thailand, this is just how its done...this is often done with the aim of just declaring your fighter unfightable, and retiring, a career arc Sylvie has wanted nothing to do with. The other thing is that size f-in matters. Give Sylvie a few pounds and its an incredible problem. Which means her victories fighting way, way up, often multiple weight classes, just shows how unique and incredible fighter she really is. She overcomes the single most determinative factor in fighting, weight, regularly. Be that as it may, it also was a good opportunity to fight with some size, even a little bit, because fighting up so much really constricts what you are even able to do, or build confidence in. She was able to bring her power down and increase accuracy, hold more relaxation in her ruup, free up her feet instead of having to brace for large bodied strikes.

-

Muay Thai, Colonialism and "Techniques" not a competition, its a celebration There is a lot that is culturally complex in how the West (and others) interact with the traditional Muay Thai of Thailand, and honestly it is worth of analysis and thinking about. It's likely full of contradictions, and doesn't present only a single picture of motivations, but...there is one thing that is pretty common place and intense, and that is the way that fighters, coaches and various purveyors of information on Muay Thai to the West, usually in the form of demo'd techniques, simply present themselves as "experts", as if their knowledge, what they came to is simply something OF them. It becomes the signature of their authority and value, especially in social media contexts where a lot of platform reach comes from "demos" of one kind or another. This is just a serious trend, a pattern. But really it is almost inexcusable when sharing or teaching others not to share where and even more importantly WHO learned something you are demoing from. Almost uniformly, it wasn't something you learned from yourself. This means, with every share you are actively erasing the past, the actual lineage of that knowledge, you are erasing the people who actually knew something more than you, and you are removing their importance for anyone who might be interested in what you are sharing. This is pretty extreme, in that it is quite widespread. One of the biggest problems Muay Thai has right now is that as it internationizes, as it reaches for more commercial markets, so many of its roots are being erased...it has less and less concrete rootedness. And while this may help it spread quickly, charged up by the popularity of influencers and such, soil without roots will just wash away when there is a change in season. The roots are what holds everything together. Further of course, if you aren't naming teachers, krus, padmen and coaches that gave you that bit of information you are undermining the entire hope of Thailand in sharing Muay Thai in the world. You are erasing the very thought that you have to go to Thailand to learn specific things (or, in other countries well educated krus and gyms), the notion that to learn something better or more completely you should go further down the coaching tree, further into the roots. This was a huge motivation for pretty much everything Sylvie has done. Her path started learning kind of psuedo-Muay Thai from a strip mall gym that had a lot of TDK in the mix, but there was the photo of a guy on the wall who had taught the head coach of the gym his Muay Thai. This was "Master K", Sylvie's first Thai teacher. What do we do? We go to the teacher of the teacher. And this is exactly what lead us to Thailand, eventually to the Muay Thai Library documentary project itself. It's been an instinct from the beginning, but also a motivating value. Shine the light backwards. The teacher always will know some things the student will not. Because the teacher's knowledge comes from something very complex, a lived experience that is full of details and reasons and contexts that don't get filtered down into the particular technique. The teacher is full of richness and intensity...and its our job to raise up and preserve the teacher, to pull them into the present, and thus into the future. And this should be done with every share of technique possible. It should be just regular, not only etiquette, but also passion to bring the sources of what you know forward with you, and build a picture of knowledge that immediately causes people to look past you, before you, when they learn something. The krus, coaches and padmen need to be known. If you've been to Thailand and trained seriously you already know that many Thai padmen in gyms in some ways know more much more about Muay Thai than you'll ever know, even if you are a very experienced fighter. Muay Thai needs for us not to erase its own past, it needs to stop cutting off the vines below the flower. It is just amazing to me that so many shares of technique do not automatically tell of where it came from...who it came from. This doesn't mean you have to authorize your knowledge, because you got it from someone more famous, or more esteemed than someone else. As I said, there are so, so many in Thailand who are just brimming with knowledge who are almost completely unknown to but a few. Common padmen just walking experts of Muay Thai, padmen who don't have even much social standing in their own gym. Lift these names. Inspire people to connect to your own knowledge tree. It's not a competition, its a celebration. There are many krus that we've documented in the Muay Thai Library who are not or were not social important krus or padmen, but they are full incredible knowledge and wisdom. Raising their names, and sharing their muay is absolutely vital, and can change their lives as well. There are so many example of this, even very famous names now. Sharing can be something as simple as: "Point your toes up on checked kicks, this is something learned from Kru Big at Sinbi [made up name] and a few other places as well" or, "Hook-lowkick is a great go-to combo, this is a mainstay of the Sitmonchai style started with Kru Dam" or, "Kru Toi always told me to use the teep more in fights, and its something I've had success in when I did it". It's just a way of talking about advice or demonstrated knowledge. Also, if this became more regular it would undercut just people cribbing demo advice from other content sharers, other influencers or breakdownists of varying quality, something that thins out the knowledge base. There isn't much wrong with learning from other sharers, but maybe just mention that you have? Create and build lineages, and inspire others to do the same. Muay Thai itself needs this.

-

I put together this compilation of little notes Sylvie has taken in a stretch of training and sharing Muay Thai, and was surprised that there is a full 30 minutes of these. I'm just struck and really almost shocked at how much knowledge she drops and the nature of it. These are not "demos" of techniques, but looking beneath or within techniques, something that comes from being closely connected to techniques for many many years, and her self-transformation. I can't think of another person in the world who could drop notes like this, of this much variety, because this just comes out of her path. These are like reading notes of Muay Thai. It's a very interesting, and kind of inspiring level of knowledge. She's a walking encyclopedia of experience and knowledge. That foot-drop taught by Manop is just this kind of thing. It's not "technique", its a piece of a technique, but its related to a generative principle that informs all sorts of other techniques, and even can touch all of your Muay Thai. There are so many of those.

-

Dropping this PDF link on market dynamics and FEP: Market Self-Learning of Signals, Impact and Optimal Trading: Invisible Hand Inference with Free Energy Igor Halperin, Ilya Feldshteyn If I ever have the time to develop more rigorously my thoughts about how the diversity, efficacy and richness of Muay Thai developed out of rural "wisdom of markets" gambling festivals:

-

Padwork porn. Ugh. It hurts my eyes. I'm not sure I've ever learned anything instructive or interesting about a fighter by watching a padwork video. Lots of things to learn about the pad holder...sometimes. Watching Karuhat on pads would never let you know what an electric, absolute GOAT of a fighter he was.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.