-

Posts

2,265 -

Joined

-

Days Won

501

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

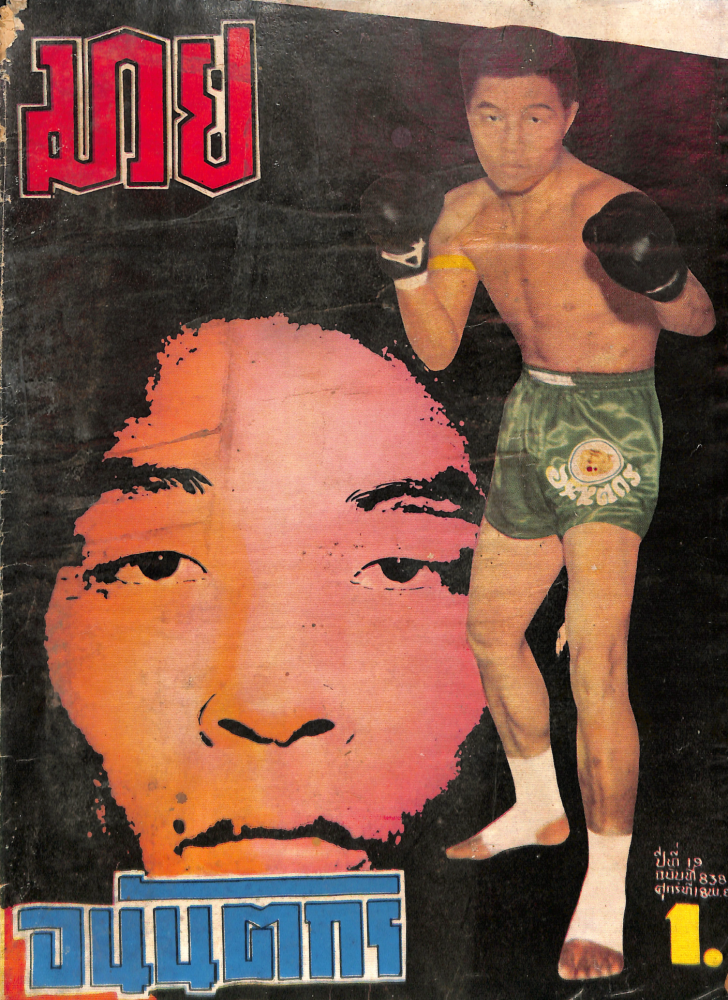

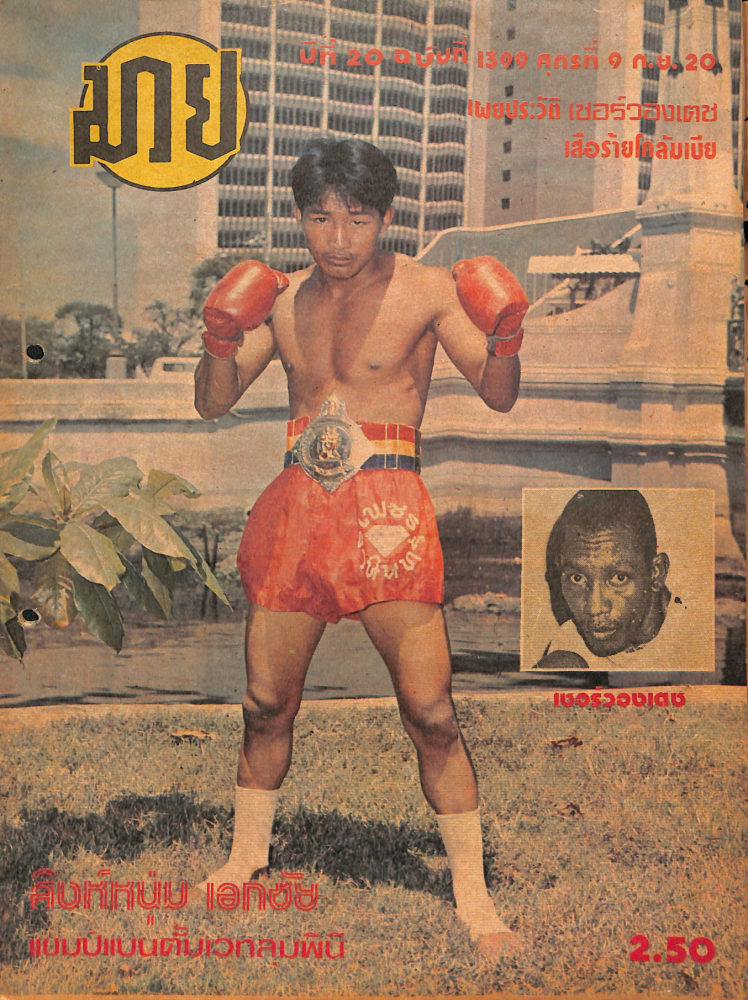

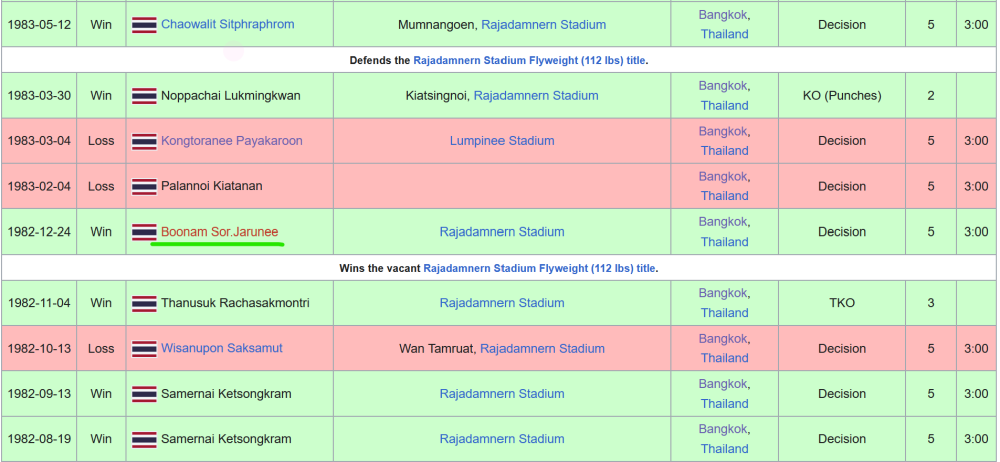

Lev brought to my attention Lankrung Kiatkriangkrai, who happens to be on the Holy Grail card, Christmas Eve of 1982, when Dieselnoi beat Samart. He's fighting Boonam Sor.Jarunee for the vacant 112 lb Rajadamnern title, and displays just a beautiful increasingly tempo'd style showing how boxing and the weapons of Muay Thai went together in early Golden Age. You can watch the fight below. He was a 1984 Olympic Boxer under the name Teeraporn Saengano. The good people of Muay Thai wikipedia, including Lev, have filled out his wikipedia page to give more anchorage of his fighting in history, a hugely important step in preserving the legacy of Muay Thai in Thailand. Without records we just have stories. You can find his wikipedia page here. This is some of his record context for the fight: Klaew Tanakul the promoter was a very big supporter of amateur Thai boxing, often financially lifting fighters up out of his own pocket, so its of no surprised that one of the best amateur boxers who was also a top Muay Thai fighter was featured on his promoted card. Video timestamped to about 25 minutes in if anything goes wrong. The fight starts very slow, but watch for his gradual uptempoing, his use of the jab, as he closes the distance round by round.

-

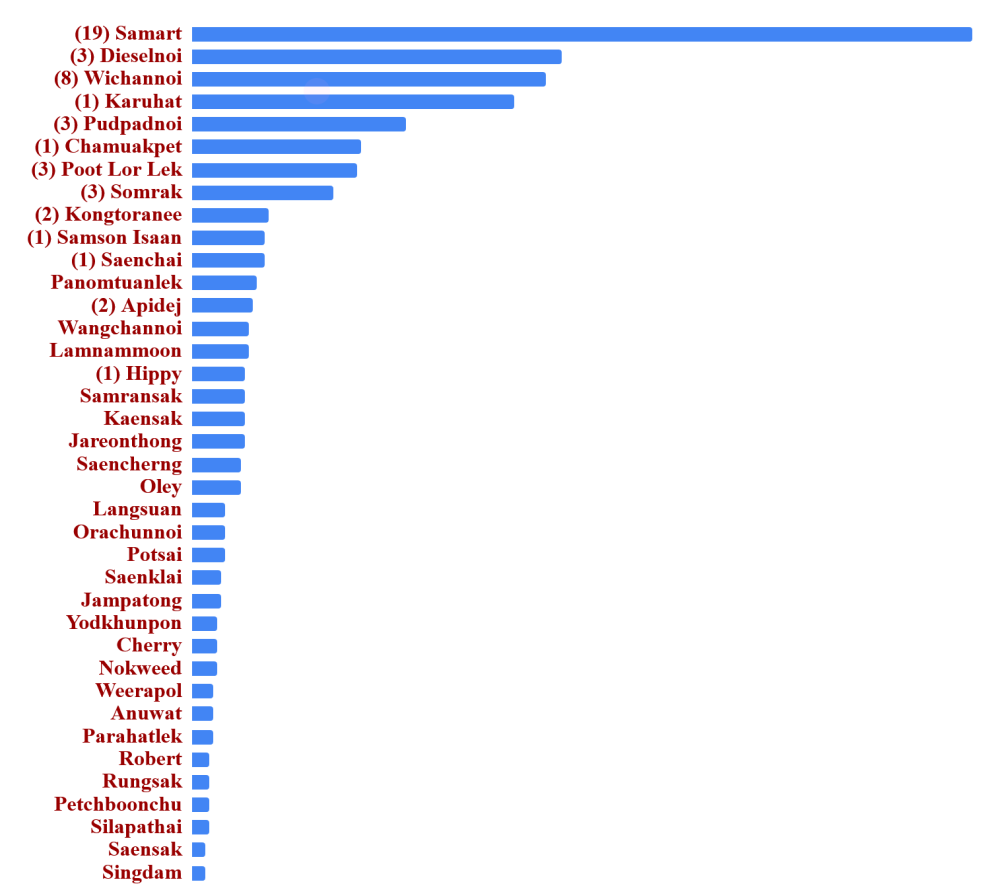

The way the power is generated, the relationship of the shin to the arc, the point of the knee in sympathy to the overall movement, the hip drive. I've been meaning to write a short entry on Kerner and the Golden Age knees of the Hapalang gym. As we've documented in the Muay Thai Library project, and in our conversations in doing that documentation, Thailand today has pretty much LOST the Hapalang knee technique. The greatest Muay Khao gym in the history of Thailand featuring 3 absolute legends of the Knee Dieselnoi, Chamuakpet and Panomtuanlek, had an expertise of kneeing that has largely gone extinct. I've mentioned it several times, watching Dieselnoi knee Kru Gai with his belly pad on, at the age of near 60 then, and blasting the pad so hard it actually stunned Kru Gai, an experienced stadium fighter kru. They were like shotgun blasts. The legends of the Golden Age and other fighters of that age have told us that today Thais knee without damage, they knee largely to score, or set up another knee, which is fine, but they have largely lost the power and precision of the Hapalang knee (and likely of many other less famous gyms of the Silver Age and Golden Age era). It's very cool that we have documented these techniques for coming generations, but the video above is also a wonderful piece of history. The French fighter Guillaume Kerner, whose original Thai teacher was the legendary Pudpadnoi, spent a year at Hapalang gym in 1985 when he was 17 years old. Dieselnoi was already retired and a said (pi) trainer, but Chamuakpet and Panomtuanlek were there ascending, peaking into their FOTY performances. He was in the middle of the greatest Muay Khao space in Thailand, right in the heart of the Golden Age, and if you watch his highlights above it shows. No farang I've ever seen knees like Kerner because he was tapped into the source, and Thais today really don't knee how he did, because so far removed from the training conditions and pedagogy that develops this kind of technique. And, his case is a beautiful one because sometimes in "convert" coming to a technique can kind of over-sharpen it, which causes aspects of it to become even more clear, and I think that's the case with Kerner's kneeing. I assume his foundations were developed with Pudpadnoi, but the art of the power, sharpness and freedom of the knee in space bears the Hapalang mark. He also trained at other notable gyms in the Golden Age, (read up on his bio here) for us like a time traveler deposited where we imagined no farang were. As someone who has studied the knee styles of the 3 Hapalang legends, and other kneeing techniques of Thailand, and watched Sylvie develop her own versions of these, in her journey as a prolific, undersized Muay Khao fighter, its actually quite beautiful to see this video. Each time I watch it I'm amazed at how much of Hapalang got transferred to him, the traces and arcs and ethic of kneeing that even Thailand today no longer really has. You can study the Hapalang 3 legends in the MTL here: Dieselnoi (1982): #48 Dieselnoi Chor. Thanasukarn - Jam Session (80 min) watch it here AND #30 Dieselnoi Chor Thanasukarn 2 - Muay Khao Craft (42 min) watch it here AND #3 Dieselnoi Chor Thanasukarn - The King of Knees (54 min) - watch it here #76 Dieselnoi Chor Thanasukarn 4 - How to Fight Tall (69 min) watch it here Chamuakphet (1985): #49 Chamuakpet Hapalang - Devastating Knee in Combination (66 min) watch it here #81 Chamuakpet Hapalang 2 - Muay Khao Internal Attacks (65 min) watch it here Panomtuanlek (1986): #131 Panomtuanlek Hapalang - The Secret of Tidal Knees (100 min) watch it here Of course there still remain in Thailand many beautiful knee styles, many of them quite effective in their own right, there have been legends and great fighters who have carried the art of the knee fighter on. But, as knee fighting has been downgraded in the sport, and in some versions outright suppressed, there is reason to fear that even more branches of the rich pedagogic tree of knowledge will be severed, as legends and great krus start to age out.

-

Note to self...want to write of the female fighter as axis mundi, the christological (in Simone Weil sense of bridging sacrifice) pinning of the body down the in the turpitude of struggle, eliciting the sparks of the divine. Soliciting the female as artist, who builds the ladder to Heaven of oneself. see Possession (1981). What do I mean by this? Some of it is in relationship to my overall theory of ring fighting in Thailand as a rite, and I think my short film was tapping into this intuition:

-

[someone posting that students shouldn't be allowed to spar without 6 months in Foundations Class] Not to respond too directly to the above statement, more to just this kind of advisement which is maybe common, but it just shows how far trad Muay Thai development was from today's class centric, out of Thailand (but probably in some parts of Thailand too) is. They are just two very different worlds and practices. Sparring, especially as it seems it was in the Golden Age...was part of foundations. Yes, there was a lot of grueling bag work or shadow boxing, but sparring playfully in space was part of young fighter development. It's not this extreme, but its a bit like saying you shouldn't get on a surf board until you have the fundamentals down for many months. The point was to assemble fundamentals in relationship to others. And, I certainly understand there are huge differences between these worlds, Westerners spar with different intents. It's only to point out that what Thais traditionally achieved was through very different sensibilities over what Muay Thai even was. It much more than this, I hope to finish an article on how trad Muay Thai is developed as social rite of passage way-of-life development, but at minimum there is a huge difference in concept in how skills should be acquired.

-

vs Narongnoi Kiatbundit 1st of 6 (130 lbs, defending Raja title, 1976-02-12) - orthodox, win Narongnoi is a very accomplished fighter of the era, twice Raja champion and robustly built. It starts out with a bit of a lowkick battle, mostly flicking kicks from both fighters. Wichannoi uses this game to establish a speed advantage and finds himself tempoing up and pressing the pocket some because he's feeling so good about it. Even uncorks a couple of heavy hand combinations, this is his element. Too fast for his opponent, but he's setting up power. Third round you can feel from Wichannoi's bounce that he's feeling it. Quick kicks with his lead leg, but he's loading his right as he likes to do. It's like a gun on a turret. There's a dual mid-clinch battle and Narongnoi comes out of it wanting to fight Wichannoi out of his spot. He's too comfortable. He definitely gets Wichannoi out of the pocket and a little stalled. He elects to take a distance and start tempoing up his quick low kicks so he can establish his rhythm again. These are fast, shin bone, flicky kicks that he specializes in. He wants to get the bounce going again. He's having trouble with the distance though and gets a little frustrated, rushes in which a combo and get clocked by Narongnoi's right square on the raw. It stuns him and he almost gets in trouble with Narongnoi's pressure that follows. He survives the round. To start to walk in, but when he does this he likes to stand in and not punch yet. Low kick first, stand in, don't leave. Then once he's planted his flag, punches in accurate combinations come. What follows is iconic Wichannoi. He walks in and stays in switching between low kicks, mid kicks and punches, but not bouncing out. Sometimes the punches come in flurries. Narongnoi no slouch with his hands tries to punch him out of the pocket, he just refuses to leave. He starts ripping uppercuts. Then wild overhands, and upper cuts. Then he starts measure-pinning with his left hand and rocking rights, one after another. Narongnoi shows incredible toughness eating punch after punch. Wichannoi will not let him out and on pivot is on him. Nothing rushed, but not calm either. By the end of the round both men are exhausted and Narongnoi's left eye seems to be closing from all those right hands. The 5th round starts with Wichannoi twice pointing to Narongnoi's left eye. It's closed, the fight should be stopped. The round which is edited for time is beautiful. Wichannoi is teeping and using long guard and bramble guard, Narongnoi is attacking...but Wichannoi is refusing to hit that eye. The accuracy is something else. He still needs his right hand to keep Narongnoi off, but he either hits the top of the head, or on the jaw, or sometimes the guard. He refuses to go after the eye. Very cool to see. vs Jocky Sitkanpai (1976-08-18) - orthodox, win a marvelous 3rd round of boxing up a Muay Khao dern fighter, using lots of jab and pivot, jabs to the body to just piece him up with his hands. Jocky adjusts and derns leading with his teep in the 4th round, trying to bring his clinch back online, and this seems to work, ending Wichannoi's boxing. But Wichannoi already has a substantial lead at that point. Wichannoi coasts to a win vs a renown knee fighter. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6OxxQLX2NQM << watch here vs Jitti Muangkhonkaen 1st of 2 (1976-09-27) - southpaw, loss after very light feeling around by both fighters, in the 3rd Jitti legally (?) trips Wichannoi in the clinch, and even seems to apologize. It wakes up the fight. Wichannoi starts to crowd him and come with combination hands...though the round stalls out in a waiting game. It looks like Wichannoi is just holding his hands at ready. Looks like there may be another hooking trip in the 4th but Wichannoi is stymied. He's just waiting to land a heavy combo, he throws a couple but Jitti's size and southpaw distance seems to hold him at bay. With the lead Jitti gets on his horse and pivots away. Movement, teeps and clinch tie-ups hold Wichannoi off. The entire fight Wichannoi looks like a dog with a bark in his mouth that never got it out. vs Narongnoi Kiatbundit 3rd of 6 (132 lbs, 1977-06-02) Round 2 Wichannoi defiant swiping with lowkicks and stiff bodied, Narongnoi equally in the space, strong. A few heavy strike by both but its basically just both claiming ground. 3rd round, muscular jousting. Neither fighter giving ground, but also fairly still. Wichannoi tries to break the ice with some aggressive combos, reversing his usual strategy of chopping through to stand in the pocket and distract. This seems like a contest of wills. Wichannoi has beaten Narongnoi the two times he's fought him so far, so perhaps he's confident that he can just stand in on him. Round 4 Wichannoi puts his head into a forward lean, which is the sign that he's coming to plant that flag, he gets rocked a little though by an uppercut in combination. Wichannoi seems undecided on what he wants to do to claim this space. He tries some of his jab and lead teep stuff, Narongnoi answers back and shifts angles. Wichannoi tries to enter with a lead rear uppercut, usually unexpected, but nothing is having effect. He has the distance he usually wants, but not really pre-preped by all his chopping kicks. He looks like he just wants to go hands to hands, and Narongnoi is countering him and defending in space. Some lead stiff arm defense is working to stymie Wichannoi, tying up Wichannoi when his hands start rocking, lead openside kicks to add points. Wichannoi is used to having to fight to get where he's being allowed, and he's not having the success he usually has when he gets there. Narongnoi has adjusted to what Wichannoi does. Allow him that close range, defend at that range, counter strike and score a little. One of the consequences of this strategy is that Wichannoi has become very still. He's at his best when he has a high tempo about him. 5th round Wichannoi's coming, a higher tick. He's changed to lead hooks and lead kicks to intiate. The hooks are in answer to the long lead stiff arm that Narongnoi has been deploying. After a mid-clinch battle Wichannoi brings the lead hooks again, Narongnoi counter with teeps and deep pivots, he's defending a lead. Wichannoi then changes to body jabs, so interesting how he does this in 5th rounds. The body jabs become head jabs, he's all lead side. A lead hook, and upper cut rattles Narongnoi. Jab, jab the jab keeps landing. He's got his cherished metronome back, but its too late. Narongnoi outfoxed him by getting him to become so still in the 4th round, giving him the ground that he usually has to fight for. vs Wichit Lukbangplasoi 2nd of 2 (135 lbs, 1977-09-23) - southpaw, win Wichit the 1974 Lumpinee Champion 135 lbs Fighting up again, a weight class up. You can tell when Wichannoi is comfortable against an opponent, he starts pressing close right away. It's usually a combination of the feeling of his speed and not fearing his opponent's power. He's hand jousting lead hand to lead and chopping through the pocket with kicks, not jumping out. Round 3 he's starting out close. He wants to be in the pocket, but not punching yet. Kicks, teeps, everything in punching range. He wants to normalize that range for when his hands go. He's right where he wants to be. He gets closer and closer kicking to normalize, his consciousness going into his hands though. He doesn't care about his kicks...he's waiting for his hands to open up. His hands start opening and the larger Wichit grabs him in the clinch to nullify. More stalking. More proximity. More lowkicks to distract. He finally buckles him with a lowkick unexpectedly, rushes Wichit as he backs away and chops him to the ground. The 4th round Wichit is aggressive, he can't afford to sit back and be chopped at. He's firing big left kicks into the openside. Wichannoi has a high tempo though, he's amped and ripping combinations, but because Wichit is no longer fading back, Wichannoi is no longer the master of range, deciding when any strike should happen. He's been forced a little off rhythm by the newly aggressive bigger opponent. They fall into some boxing, and Wichannoi has the speed and accuracy advantage, plus he's got low kicks to throw in. His tempo is high. Wichit tries to bounce himself into a higher tempo, catch on. Wichannoi is left with his stinging lowkicks at range as Wichit throws hands at range. The round ends with neither fighter being where they want to be, each off tempo. Wichannoi starts the 5th round with his head bent low, he's focusing on the lower body. Jabs to the body, teeps to the body, some boxing movement. He's attacking under that lead hand from the southpaw, it must have been bothering him. An interesting adjustment for a final round. Wichit tries to counter by clinch grabbing and knees in space to mixed results, an interesting counter to the body attacks. Wichannoi starts boxing in combinations and continues to teep the liver, fighting off the clinch and knees, adjustment on the adjustment. Combinations, deep pivots, teeps, its really a beautiful round of fighting stylistics by Wichannoi, establishing the space and tempo he wants, not letting Wichit's size dictate. A very nice victory. vs Padejseuk Pisanurachan 3rd of 3 (130 lbs, 1980-03-05) - southpaw, loss Fighting the 1979 fighter of the year fight a little over a month after Wichannoi had lost to Dieselnoi. Dieselnoi would after this fight avenge his own loss to Padejsuek, so this is the top 3 fighters in a round robin of sorts, but Wichannoi doesn't look to be in his usually rock hard body shape. In round 2 Wichannoi is jabbing, crashing in with his right, but Padejsuek is boxing him off aggressively, not letting him stand where he wants. Round 3 Wichannoi has his tempo up which he likes. His right hand is in the defensive mitt position which means Padejsuek's power was bothering him. Padejsuek is using a boxing jab, movement and a switch lead kick to the openside to counter and keep Wichannoit from coming in. Then Padejsuek starts to attack with hands. He's long and powerful and driving Wichannoi back across the ring. He's an accomplished boxer having won the Raja boxing belt, and his long powerful, lancing style is trouble for Wichannoi who wants to wade in. Wichannoi tries to stand in, that's his style, which means he has to trade, but Padejsuek is a handful, adding in step knees under his hands. Padejsuek is ripping powerful over hands and hooks forcing Wichannoi to give ground with his long bramble guard in protection. Padejsuek has size and he's using it with fast paced hand in succession. Wichannoi has to resort to jabbing him off hard. It's a difficult round. 4th round Wichannoi has moved his right's knuckles forward, his offensive position. He want to stand in and trade if he has to. He's using bramble guard and jab, but he's being beaten back. He tries stiff arming with his lead hand, to no avail. Then he moves to the switch kick to the openside combined with jabs to the body, trying to soften the liver and get under Padejsuek's boxing. Some of those kicks are landing, some of the body shots, including his right, its slowing down Padejsuek. More jabs to the body on retreat, he's got to get to the point where he can stand in, he's still fighting off. He's keeping low, hiding behind his jab, shoots for a mid-clinch and throws Padejsuek to the ground. He's doing his best, making inroads, but he's still in retreat which isn't his game. That throw looks like it took a little wind out of Padejsuek and it allows Wichannoi enough space to start opening up his tool box of hands. Upper cuts come, an overhand, triple jab and switch kick. His tempo is high where he likes it and for the first time he's in his zone. More body jabs followed by the lead kick to the body, a very cool linkage. He's finally got Padejsuek a little frozen. A jab and cross to the body. Padejsuek feels the moment and lunges forward with hands, driving Wichannoi back, but Wichannoi lands a counter right elbow that lands (but doesn't cut) stunning Padejsuek for a moment, he didn't see or expect that. He backs up for a moment teeping to recover, than attacks again. More fast body jabs in retreat, and that lead kick to the liver on follow. A very sweet front side game from Wichannoi. His high tempo totally has Padejsuek off kilter, its a remarkable reversal from the 3rd round where it just looked like Wichannoi couldn't handle the boxing skills that were coming at him, like he was being outclassed. Man that jab was really working against the longer Padejsuek, put weather on him. 5th round comes and Padejsuek has made an adjustment. He stole Wichannoi's lead kick to the open side and is just spamming it with length. He's using that kick to complicate the pocket and deny that jabbing game. Then he collapses the pocket with double plum grabs and knees that as the taller fighter score very well. He's taking away everything that Wichannoi was doing to him in the 4th. Wichannoi tries to go back to the body and Padejsuek just double plums him and knees (likely how Dieselnoi did in his victory over Wichannoi). He basically has turned into Dieselnoi. Wichannoi is in retreat, tries to turn the body jabs and now a liver teep up. Padejsuek just goes to Dieselnoi like long stabbing knees, throwing elbows on top which was a specialty of his. He feels the lead and retreats, loading his Dieselnoi knees as ready counters if Wichannoi wades in with punches as he has to. It's actually an amazing round, because we basically get to see how Dieselnoi finally beat Wichannoi (a fight which has no video). He come in with a high long guard, Dieselnoi style, and long stabbing knees, and to finish the fight off he double plums with straight knees as if signing Dieselnoi's signature. Padejsuek would lose to Dieselnoi two months later. The adjustments and swings in this fight are incredible. Not that certain strikes changed things, stylistics changed things. Answer to answer. Wichannoi had swung the fight to himself in the 4th, Padejsuek became Dieslenoi to win it in the 5th.

-

Wichannoi Porntawee is a fighter like no other in the history of Thailand's Muay Thai. While many in Anglophone Muay Thai conversations had hardly heard of him, when legends put him at the top of their picks for the greatest Muay Thai fighters in history we picked up our ears. He fought with a very boxing based, combination heavy foundation at close range, but had a highly developed style for controlling all ranges, often facing powerful fighters much bigger than himself, which for me is always a key to measuring greatness. He was nicknamed The Immortal Yodmuay (legendary nakmuay), and Dieselinoi, himself a GOAT candidate, called him "my teacher in the ring", Wichannoi the man who stopped Dieselnoi's 20+ fight win streak and meteoric rise to stardom, with back to back wins against the much taller fighter who was wrecking everyone. Watching his fights one night, one after the other, all 11 which exist, was an extraordinary experience, I think the most intense and education video watching experience I've had in my study of the art and sport. Below are my watching notes and each of the fights in chronological order. You can find Wichannoi's complete record on Wikipedia thanks to the great work Muay Thai wikipedia has been doing giving us all a foothold in history. This is a very good breakdown of the weapons and tendencies of Wichannoi by Ryan. It's excellent. Its well worth the time even though the illustrative gifs no longer exist. A summary of his style objectives: Some of what follows stems from my philosophy that fighting is a struggle over time and space, and less really a question of technical striking which is usually overemphasized when discussing the aims of a fighter. For me fighters are usually trying to get to the right space and at the right tempo where they hold superiority, and conversely preventing their opponent from doing the same. It's more of a temporal-cartographic concept of fighting. I usually watch with two questions: where do they want to get? What tempo do they want to be at? This is just what I see from a close watch of all 11 of Wichannoi's fights. It's not necessarily correct, just a sharing of what I saw and noted for myself. The notes weren't really for anyone else, but I share them because you might write your own when you watch. Wichannoi's primary objective in a fight is to get to a sweet spot, which is pretty deep in the pocket. Ideally he wants to stand there with his hands at ready, in a state of measuring. Normally a Muay Maat fighter would be punching their way into the pocket to get to this spot, but he's very different. He wants to stand there and measure, and the means by which he does this often with lots of low kicks, and mid- kicks at close range. He does this to stabilize the striking zone, and its really extraordinary to see it unfold. He wants to be the eye of the storm, and leave you standing in the storm. When he gets there like in the first Naraongnoi fight, he can be devastating. Of course his opponent isn't going to cooperate most of the time, so a lot of the early portions of fights are feel out rounds where he starts working on the legs from distance, with quick timed slapping kicks (you find this lineage of Muay Maat in Golden Age fighters like Takrowlek or Thongchai but in those cases hands and kicks are more joined together, Rambaa also deploys some of this outside fighting). These are all small bodied Muay Maat fighters. With Wichannoi its not really in-and-out fighting so much as that he's wearing down the edges of the pocket he wants to stand in later. He's taking down the outer walls of the citadel. On top of this quick kicking game he also can deploy a beautiful use of body jabs (highly unusual in the sport) and at times lots of boxing jab work to the head to compliment. These are part of his tempoing up. When he enters he wants the tempo going. In Wichannoi's case the fight has an arc and he is using all these weapons to get into a calm pocket - he actually wants to get to his sweetspot in a state of survey. Once he gets there he is using low kicks largely to freeze his opponent so he can measure, his hands waiting. But, what makes it so instructive is that many of these preserved fights he is fighting much larger, highly skilled fighters, so he can't really get to or stay in the spot. Against the giant Saensak Muangsurin he absolutely could not get there at all, and as soon as he was close enough he was smashed. Against Padejsuek, again too much power and size in front of him, he ended up having to manufacture a lead with backwards jabbing and body attacks, just to control Padejsuek enough to get to some state of equilibrium. He wants that equilibrium up close, he believes he can win it. And...he wants that tempo climbing up when he gets there (the lack of this tempoing was a fatal error in his 3rd fight vs Narongnoi who simply allowed him his spot, but at stagnant energy, and defended). As opponents that prevent him from achieving that sweetspot, in that failing you can see all the diverse skills he used to still try and get there, all the ways he tried to solve the problem. You see a great fighter exploring solutions - he isn't just doing one thing, like a cartoon of just lowkicking to get in and punch. And you learn a lot about other Silver Age fighters who are very adept at denying what a fighter wants to do. It is said of today's trad Muay Thai that nobody "solves" anything anymore. They have their specialty and they can either impose it or not. There is very little shifting of approaches. These fights contain so much solving and counter solving, especially from round to round, they are an education in themselves. Because Wichannoi is smaller in stature and relies heavily on his hands in combination if he can't get to his sweet spot he often has very few chances to win, especially against the top tier talent he was facing. So the joy is watching him invent solutions, even when they fail. He's a bit like a great clinch fighter who has to get to the clinch, the lock, the swim, and if he can't get there he may not win, but instead Wichannoi's an in-the-pocket equilibrium fighter, who wants to deploy his hands...on his time, under his terms. He's willing to trade, but that's not what he wants to do. He wants to stand there and look, up close, while whacking you with his lower body, and then get the ball rolling with his hands. And once its rolling, to keep it rolling hard imposing intimidation if he can. So many of his fights are filled with compromises with this, but that is where we get to see his extraordinary skill and improvisation. For me, once I realized the goal of it all, then all the pathways to that goal suddenly stood out. Everything he's doing from the outside isn't really to win the fight, and he's very skilled there. It's to prepare the ground for where he wants to be. Sometimes he can only be there for a second, like when he knocks out Pudpadnoi in their first match, sometimes its almost an entire round like with Narongnoi. Fights I'd say to watch as Don't Miss are that first Narongnoi fight, the fight vs Padejsuek which is a fight of incredible compromise and recalibration. His fight vs Sirimongkol is beautiful because he's facing a bigger boxer who is slick and long, and just refuses his spot. They are all actually really good at teaching the use of tempoing, of spatial goal setting, of combining level change and use of angle taking. He's just really a profound fighter who was regularly struggling vs size disparities. The Fights and Notes The notes that follow below are varied. Some of them were just personal notations so that I can recall later what were essential characteristics or turning points in a fight, so that I can recall them more easily. And some are quite lengthy moment to moment perceptions, where my understanding of Wichannoi is really expanding in real time. The watch started out as mostly the attempt to recall a particular fight that I enjoyed, but became a full blown fight after fight watch study attempting to assess and record just what was so special/unique about Wichannoi. What was he about? As notes I tried to clean them up but typos may be plentiful. vs Pudpadnoi Worawut 1st of 3 (1971-12-17) - southpaw, win a very femeu fight vs one of the great femeu fighters in history. Lots of quick low kicks and pivots, lots of positioning. Then in the 4th Wichannoi uncorks a quick 2 punch combo that lays Pudpadnoi out. The only time Wichannoi would beat Pudpadnoi in their 3 match ups. the fight: Huasai Sitthiboonlert (139 lbs, 1973-06-22) - orthodox, win fight waaay up, you can see the visible size difference. Early Wichannoi is just picking at the legs. Huasai look like a ponderous boxer with power. Huasai starts bringing the fight to him, a deep pivot out by Huasai puts him against the ropes. Wichannoi measures and puts him out with a powerful right hand just as Huasai opens up to punch, and even rips an elbow or a tight hook, just missing the falling Huasai. Huasai looks done laying their motionless, and then suddenly springs up energetically to life. Wichannoi pressures and pounces, never snuffing his punches, always liquid in range, landing combinations and putting Huasai down again. He's up again on the count the giant who cannot be killed. Wichannoi catches him on a dive out next, landing a hook and declared the winner with 3 knockdowns in the round. Does several somersaults in celebration. vs Sirimonkol Looksiripat 2nd of 2 (134 lbs vs 136 lbs, 1973-10-26) - southpaw, loss giving up two pounds vs a the future FOTY (1973), a legend of the sport. Early on big weapons are out. Sirimongkok is openside southpaw kick blasting and throwing his straight, Wichannoi knocks him down (no count) with a right straight of his own. Sirimongkol's big kick and boxing keep Wichannoi waiting, and he even rips a kickout trip on Wichannoi. He has more weapons with force. Against the added size Wichannoi can't intimidate with his own power. 3rd round Wichannoi has decided to chop the lead leg down, a favorite against southpaw. Quick inside and outside kicks. Sirimongkok adjust, keeping things long, and teeping with his lead leg to avoid it being excessively targeted. Wichannoi heats up his boxing combinations closing the space, but Sirimongkol has boxing himself, and keeps it long with jabs, slipping Wichannoi's best punches, jabbing and pivoting out. He also answers Wichannoi's tough leg kicks with powerful leg kicks of his own, giving him game to game. 4th round you can just feel that Wichannoi wants to land powerful hand combinations, and he's holding them in wait, only throwing them occasionally. Sirimongkol is still keeping it long with his boxing and a few openside kicks, its mostly about distance. He's also added a left knee in space this round, which is a weapon tailored to beat a boxer. Sirimongkol uses his size and maybe even strength advantage to just deal back Wichannoi whatever he offers, even winning at trading punches. Again, game on game. Wichannoi just can't get to his sweetspot with his hands, and even when he does Sirimongkol just fights him out of it. 5th round Wichannoi is just determined to get to his spot and stay there. He pressures and buckles Sirimongkol some with low kicks. Sirimongkol is doing everything to get him off his spot. Jabbing out, trading low kick for low kick, Wichannoi is staying where he needs and is waiting for his big punch to land. The battle of distance and Wichannoi finally planting his flag is what this fight is about. Sirimongkol finally grabs him to stall it out, but after the break Wichannoi lands a painful low kick and a heavy cross. Sirimongkol grabs to stall, but then shoves off. Wichannoi wades in with pseudo clinch, and then kicks out Sirimongkol's ankle dropping him to the ground. Wichannoi is bringing his legendary toughness, he feels he has a window late. He's trying to kill that leg, staying in. Sirimonkol's deep boxing pivots to the left save him. Wichannoi started too late, and in the end Sirimongkol's size and boxing was enough. vs Saensak Muangsurin 3rd of 3 (1974-08-22) - southpaw, loss Fighting way up vs the 140 lb Lumpinee champion. This fight is a difficult and indeed dangerous fight stylistically. Saensak's known for just sitting on his huge left hand. He has tremendous power. Wichannoi likes to encroach with kicks, eventually stand in and keep his right hand there loaded with power...but he almost always throws his right in combinations. To sit in the pocket though, while Saensak who is two weight classes bigger trains his .44 magnum at him is just asking for pain, and Wichannoi starts this fight tentatively at distance, holding his right glove like a trainers mitt. It's purely devoided to defense. There is some hand fighting as Saensak's .44 is pointed at Wichannoi's smaller caliber with a kick, Saensak crashes in with a straight and its a lot. Wichannoi shifts at the angles, pings at the legs, but its very unclear what he can do. That big left is staring at him. He lands an off-rhythm straight, no combination, and it does nothing. In the 2nd round Saensak realizes that he has control over both range and power and fights passively, backing up, just letting his left wait for Wichannoi to come in. He has to come in, there is no way else to win this fight. Wichannoi starts bouncing around to bring rhythm, this is kind of one of his triggers, and Saensak follows him in it, bringing more life to his own feet. Saensak has long, slow openside kicks that land because Wichannoi is seriously worried about that left. His lead growing. 3rd round Wichannoi has turned the knuckles of his right hand a little bit more forward, its no longer just a trainer's mitt. He's creeping in as he likes to do, usually he wants to plant that flag and punish with lowkicks, but Saensak is beast and even his misses are frightening. Wichannoi tries with lead hand to hand pressure with then his right, or a short body kick. Somehow he needs to get to his spot, he's standing in. Saensak throws an absolutely blazingly fast 2-5-2 combination where the first 2 isn't even a complete punch. It's just a gesture which opens up the guard, the 5 and the next 2 knocking Wichannoi out. wow. Saensak doesn't throw a lot of combinations but this one is just incredibly fast and accurate, and it delivers the left hand bomb. Because Wichannoi is so wary of that left hand that 2 to start just opens him up. He walked into the exact buzzsaw he feared, but some craft with it. They fought 3x, Wichannoi had beaten him 2 years before (I can't imagine how). Saensak: King's Fighter of the Year in 1973, WBC World Boxing Champion vs Pudpadnoi 3rd of 3 (1976-05-27) - southpaw, loss the fight starts out with a bit of range-finding but it becomes clear that the range that Wichannoi is looking for his Muay Maat punching range. He's pressuring, differently than in fight 1. Lots of powerful (rather than flicking) lowkicks early. Round 4 Wichannoi's power kicking game is turned up. Not only kicks to the legs but also to the open side, always measuring for a big right hand. Pudpadnoi is just slippery enough and lands two big kicks with his famous left leg, but Wichannoi had him flinching on low kicks too. He couldn't land his right though. In the 5th Wichannoi still kicking but you can feel he wants to land his heavy hands, the fight is staked on it. He is waiting, but the Golden Leg of Pudpadnoi holds the fort.

-

In thinking about Muay Thai training techniques, and the deploy of techniques in fighting, I always turn to a chess analogy. There are "bad" moves one can make against mediocre players, that are in fact "good" moves in terms of results. But, it feels questionable to learn and train "bad" moves of this kind, not only because you might run into a strong player - you might, or you might not - but also because when you learn bad moves, and don't see "why" they are bad or weak, you just don't understand the game at a necessary level. The whole point of looking at moves and thinking about this is understanding the underlying principles that make moves (or tactics, or strategies) good or bad, so that in thinking at that level, you can creatively and spontaneously create novel moves for a given situation. There is an interesting sub-example of this floating out there, the "don't turn your lead foot on a hook in Muay Thai because you'll get kicked". There are layers to this idea. The first is the idea that "sure, you can get away with this against a poor opponent, but if you fight a good one, you'll get kicked". Sounds good, sound penetrating, along the lines which are above. But, not the case. There are any number of ways that this isn't really a readymade practical danger, no matter the skill quality of an opponent. Strikes always exposed oneself to counters. The efficacy or dangers of strikes relies very heavily on set up and situation. What is your range? What comes before and after? A 100 questions that matter. There isn't really just a "if you do x, y will happen", and a lot of the discussion of techniques falls into this error. You can't boxing slip or you'll get kneed. You can't body punch or you'll get elbowed. There are always trade-offs, and its important to see potential weaknesses, but honestly getting calf kicked with a turned foot (which isn't likely to happen at the right distance in most effective hook throwing scenarios) isn't that much different than getting your calf kicked without your foot being turned, in fact if you are weight transferring to your back foot its probably not a major problem...and if its a problem, you adjust. Is your foot outside the stance of your opponent? How far are you, what is the distance? Are you proximate enough? What did you just throw? What are the trade-offs? Inotherwords you need to look at all the pieces on the board. Instead you just get meme'd wisdom. If you do x, y will happen. This is the layering of the chess analogy. This is when we think about the larger picture, the larger principles. In some cases turning your foot may not be optimal, but in others it may give you several trade-off advantages. Some of this goes to the philosophy of the hook itself, why you are using it and how are you generating power? In general though, its worthy to move past the "it works it must be good!" assumption, because there may be larger principle reasons why it will not work against a better opponent, or, the success of the technique may mislead you into thinking a whole class of approaches are fundamentally sound. But, on another level, any question of soundness because of reason "x" also has to be put in larger context of how it matters how a strike is executed, how strikes work in concert, and the trade-offs of offense and defense.

-

Because I've mostly studied the Golden Age of Muay Thai and after I'm often of the opinion that "Muay Thai doesn't have combinations"...and this is often true. The use of punches are much more vision driven and creative, and at times very good boxers like Somrak won't even be throwing punches, but will be using boxing's footwork or angle taking. But...if you go back to the 1970s many Muay Thai fighters did use boxing combinations to great effect, perhaps no fighter more than the great Wichannoi who punches with speed and power along a grammar of combination fighting. In fact after watching all his fights last night I think one could say that his entire style is organized around his close range combination Muay Maat attack. It's very clear how important they are to him. Last night I also put this brief edit of a 2-5-2 knockout combination that Saensak used to knockout Wichannoi, which is just electric. It really works because Saensak has a thunderous left that Wichannoi is very wary of and has to commit to shut down. But, in the story of boxing's influence on Thailand's Muay Thai that goes back to at least the 1920s, it does seem that there was a qualitative change between the 1970s, then the 1980s, then the 1990s. It's almost as if Western Boxing was digested by Muay Thai, and its influence became more and more diffused, affecting more and more elements, but also less standing out stylistically through combinations. Golden Age punching styles took on their own unique character, through a widespread integration. One of the interesting things is that because Thailand is becoming combination oriented in its training, with the influence of Westerners and the rise of Entertainment Muay Thai, the Silver Age with its much more distinct combination fighting may be a better touchstone than Golden Age excellence. And Wichannoi in particular perhaps.

-

Geez. I spent the whole night watching all 11 of the existing fights of Wichannoi Pontawee, who many legends named as the GOAT. I've watched his fights before and have enjoyed them, and a few times wowed, but I felt like he's just too important a fighter to be only "somewhat" familiar with him. I had crisp idea of how he fought, and I saw him have some spectacular moments. But its an entire different thing to sit down and watch all the fights - taking lots of notes - back to back, one after another. I don't think I've learned as much watching any other fighter. It's remarkable. Hopefully I can put these notes together for others.

-

One of the effects of deteriorating defense in Muay Thai is that sub-optimal offenses will become more effective. Which is to say, they will no longer appear sub-optimal (based on flawed principles). The lack of eyes, or distance control, or sound principles on defense will elevate certain offensive trends which would never fly in the past...one of the subtle ways deskilling is happening. Basic combo-ing sudden is proven effective. Blind pocket trading, effective. Spamming elbows, effective. And with that effectiveness the loss of skill.

-

One of the great ethical difficulties to the above is: Do you want to make visible what is currently invisible to the cartographic appropriations of colonial capital? Or, just let them sit safely out of range, in their unseen character? On one hand it feels like you must make them visible so to marshall forces to protect and safeguard, and even possibly restore; on the other hand by mapping the invisible then you just set the conditions for appropriation and distortion, and eventual elimination. One of the aspects which I believe kept Thailand's Muay Thai so resilient, despite so many international influences (probably for 500 years even), is a certain kind of hermetic quality to provincial Siam/Thailand, the way that there are cultural dividing lines, which provincial ways of life and culture exist in their own right, than you are passing into another "land".

-

This is an English translation of a Facebook post written in Thai by a prominent figure of Southern Muay Thai, protesting the new government and stadium changes brought to make Muay Thai more amenable to foreigners. A lot of truth here in how the knowledge of the sport actually lays within the villages and at the festival level...some of this language is quite strong though, far beyond Thai etiquette. Just posting it here because many don't realize that there are Thais that firmly resist these changes, and see them as undermining the sport and art itself: "I have been in Muay Thai my whole life. I've been in it before it became corporate. I've stayed in it with love for the sport. Muay Thai is a poor people's sport. Only children of poor families will fight. In the past, this was a "mafia" sport. Hence, no organization wants to get involved. However, this sport still does things the countryside way. Fights relies on temple fairs and annual events. Rules and regulations that are used were made by the people who of Muay Thai who truly understands it. For example; the 5 rounds, 3 minutes per round and 2 minutes break, weigh-in in the morning. It's all made for fairness, even if the bigger fighter will gain an advantage if the fight is at night time, because morning weigh-ins will impact a fighter's management. In the current day, rules are about to change, because the organizations responsible for Muay Thai do not understand the life of the people of Muay Thai. They don't understand fighting in the Muay Thai way. They attempt to compare Muay Thai with the foreigner's martial arts. They try to shove foreigner's rules on to the roots of our sport and tell us it is universal. They are trying to change our way of life by washing away our Thai identity with their papers and regulations. They bring specialists who've never made any contact with the sport to write the rules without asking of what the people who will be following these rules and bequest the national arts think about the rules. This is borderline of selling the country, selling it's traditions, selling your own roots, just to impress foreigners. The spirits of the ancestors will call you damned children."

-

Been pondering a new style gym, but one radically different than what Thailand knows. Something of a studio. And even a profit sharing concept...but I suspect that Sylvie will never let me do this, as she really doesn't want anything to do with having or running a gym. But, it may not be what she thinks. It's a space like some spaces, many moments really, we have experienced in Thailand, where "Muay Thai happens". It's not practiced, its not done. It "happens". There could be an environment like this, which is not lost to the restrictive difficulties of the past, or the vast commercializations that are coming. This would necessarily not be a "successful" gym. In fact it would be structurally against any such possibility. Much more like an experiment in Muay Thai thought, a small island...which then might echo out and influence other spaces, spaces we are not really interested in. #idea

-

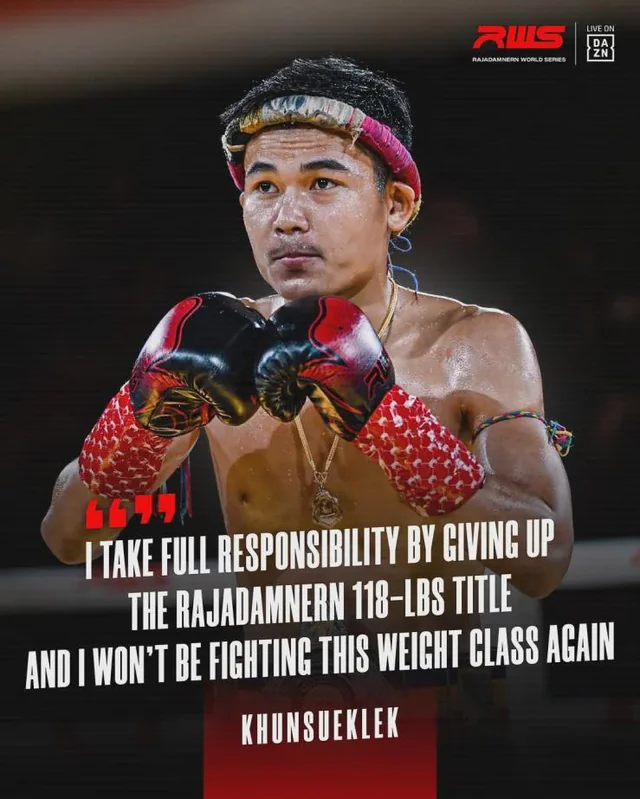

This will be one of the significant challenges of trad Thai fighters going forward. They are increasingly not within the discipline and authority of the kaimuay system which developed them when young (socio-economic changes are creating a new autonomy and a cross-mix of progressive motivations) and Thailand's Muay Thai is being bent toward Western style weight cutting with new weigh-in processes. The Science of weight cutting of the trad kaimuay is made for the trad fighting system, and of the kaimuay subculture. As those disciplines become loosened they will find the new world of weight cutting competition quite difficult. There will be a lot of missed weights in the New Muay Thai that is coming. I don't know about his particular situation, but it does provoke these thoughts I've had about an increasing trend. Thais in trad Muay Thai really seldom missed weight by custom. Trad fighters near the top of the sport are going to be caught between (non-rigorously applied) Thai cutting practices, Western cutting practice suggestions (a bad combination because Thai & Western cutting is very different), amid bigger weight cutting demands. They'll find themselves chasing down big cuts late (or just deciding not to make weight like Superlek vs Rodtang), which could incur not only bad or weak cuts, but also real risk. As I've written about before..."professionalism", which is a Western concept and identity trait, is not Thai, especially in the fighter subculture. The motivations and shapes of training as fighters - that which produced the best fighters in the world - are not those of "the professional". "Be professional" is not a Thai prescription. The cultural bounds of the kaimuay, its hierarchies, social obligation and shame are often what held a fighter's weight in check...these things are loosening, if not in some cases becoming undone all together. Khunsueklek (the purported best Muay Thai fighter in Thailand) misses weight, gives up his Raja belt. He had to go to the emergency room.

-

ONE didn't invent giving bonuses on top of fight pay in Thailand. In fact it took a long tradition of gamblers providing injections during fights to inspire fighters. When you hear about traditional fight pay you are missing out on the "injection" bonuses which can be substantial. Here today a fighter winning 500,000 injection bonus ($15,000+ USD) and being guided into the stands to thank the gamblers (who are often portrayed in simplistic caricatured ways). It's an ecosystem out of balance, but its still an ecosystem, in which parts support parts. Instead in ONE this bonus tradition has been transferred to only ONE big boss, being handed out on the preference of a single man, who is attempting to steer the aesthetic of Muay Thai itself...away from tradition. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=791304983340912&rdid=mUWvMklDzJ4i3xa6

-

Watched this fight yesterday, and was really moved by Devy. Looking back at Bill's skills he's everything Entertainment Muay Thai dreams of for a fighter, mixing combinations with Thai techniques, eyes and timing. Beautiful stuff. But Devy is incredible...in such a subtle way. He's like: I'm take your pyrotechniques and just hold position and cover, then move the set, take, hold blast a lowkick to your back thigh. It's like watching a chef cook a masterpiece with 3 ingredients. It really doesn't matter who won this fight, its up over 150 lbs, its the art of this cloistered, minimalist fighting, and his shrug-offs of the aggression and attempts to intimidate. Bill probably the most skilled Western fighter in history, but something deeper and older going on here with Devy. Something that is almost painful to receive beamed across the decades to here and now, as everyone is trying to push Muay Thai into Entertainment and Westernization, Globalization.

-

Saenchai with another KO win on Entertainment Thai Fight. He's the last magical fighter of Thailand, that last of Thailand's greatness, and we are all blessed as he continues in the ring. I don't watch it much (or any of Thai Fight), but still consider it a blessing. When he stops it will all be gone, even though this is kind of half-fighting, and surely he'll do show fights after his retirement. What I love about this photo - and the first thing is that it suddenly feels like Saenchai has aged, and this happens - but what I love about this photo is that you can see his "coal eyes", which is what I call them. There was an old trainer at Lanna named Nok, who when you trained with him his eyes, if you got any advantage or edge, would just turn black. You could see, he just went into that state. And you knew, stop fucking around. Saenchai has always had such a joyful, playful visage, and a charm of handsomeness that he carried everywhere, even into intense battles. But every great, experienced fighter, even Saenchai, has "coal eyes" inside of him, they have to or they couldn't do it the way that they have. And, in my poetic view, it feels like in this slightly aged photo you can see his coal eyes come out. And its really beautiful.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

.thumb.jpg.a4c51d2fdfe94a529a911dbeec75c411.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.73ecaa510849d11bf4120944c8ad2465.jpg)

.thumb.jpeg.f9dae93f814d0abbfafe4cc2a8b08f40.jpeg)