-

Posts

1,719 -

Joined

-

Days Won

419

Posts posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

-

The above video is from almost 11 years ago. Sylvie is up the Hudson River where we lived, taking the train down to NYC to train in a Muay Thai gym in the city, more than an hour away from the small town we made our home. This video just gives me quiet tears, hearing her sincerity in response to some pretty harsh commentary coming through YouTube. One of the things Sylvie was exposed to was, from the beginning, being an outsider to "Muay Thai" proper. She was training with a 70 year old man in his basement in New Jersey, an hour and a half's drive away. She was putting up videos of her training because there was nobody like Master K, her first instructor, online anywhere. There was pretty much nothing of "Thai" Muay Thai online. A small community of interested people grew around her channel, but also came the criticism. From the beginning there was a who-do-you-think-you-are tone from many. You can hear it in her voice. She doesn't think she is anyone. She just loves Muay Thai. She's the girl who loves Muay Thai.

I cry in part because many of the themes in this video are actually still operating today. She's a huge name in the sport, but personally she is really still just the girl who loves Muay Thai, who takes the alternate path, doesn't ride with gyms, doesn't care about belts, doesn't want to fight Westernized Muay Thai. She's burned a path into Thailand's Muay Thai for many, but she's just replaced Master K - who to this day loves Muay Thai as much as anyone we've ever, ever met, with the possible exception of Dieselnoi - with legends of the sport. Karuhat, Dieselnoi, Yodkhunpon, Samson, Sagat. These are her fight family. And the same quiver is in her voice when she thinks about, actually yearns for, their muay. Wanting to be a part of it, to express it. From someone on the inside, it's just striking how little of this has changed, though like a spiral it has been every climbing higher, towards more ratified and accomplished feat, many of them feats that nobody will duplicate...simply because she's just The Girl Who Loves Muay Thai, and is taking the alternate path. She's running through the foothills of Thailand's greatness. And like then, when people in Muay Thai criticized her, today she has the same. The same unbelievers. And it's as pained today as it was on this day in the video. What's remarkable about her journey is that it necessarily has involved sharing, exposing, all of her flaws to everyone. She's likely the most documented fighter in history. We've put up video of every single fight and probably a 1,000 of hours of training. She has lived herself as exposed to everyone, as much as a fighter can be.

What I'm amazed by, watching this 11 years on, is her equipoise, her balance in holding the harshness of others, and her lack of ego in all that she was doing. One of the most difficult things she's encountered in developing as a fighter, reaching for the muay of yodmuay, is actually developing an ego, a pride or dignity, which is defended not only in the ring, but also in Life. How does one get from the above, to where one needs to be as a fighter? What internal transformations have to occur?

I happened upon the above video today, the same day Sylvie posted a new vlog talking about her experiences in training with some IFMA team teens at her gym. She was reflecting on how many of the lessons of growth she had not been ready for as a person years ago, especially lessons about frustration and even anger. You can hear the frustration in the video at the top. Mostly it falls behind a "I mean no harm" confession. She's just loving Muay Thai and sharing it. The impulse of those shared early videos of Master K eventually became the Muay Thai Library documentary project, likely the largest, most thorough documentation archive of a fighting art in history of the world. It's the same person doing the same thing. Even to this day, nothing of this has changed. But, what has changed is the depth of her experience, in over a decade of love for the sport, and in fighting an incredible 268 fights, and counting. Take a look at the vlog she put up today, and see what has changed. From the above has come one of the most impactful western Muay Thai fighters in history, both as a person and as a fighter. And the mountain is still being climbed:

-

1

1

-

1

-

-

What is interesting about this is that it is one of the few steps taken at the New New Lumpinee which doesn't seem like a bend toward Western (or Internationalist) ideas and instead is broadly in support of the ecosystem which has produced Thailand kaimuay Muay Thai superiority for decades. Modernist views are against children or early youth full contact fighting, but in this case Lumpinee is lending its name to younger fighters, in hopes of developing stars and their following much earlier in their lives. No matter what one thinks of child fighting in Thailand its a fundamental part of why Thais fight like no other people in the world, just in terms of skill. Interesting to see Lumpinee leaning into something there has been pushback on.

-

This is our latest Muay Thai Bones podcast where we discuss MMA coming to Lumpinee stadium:

-

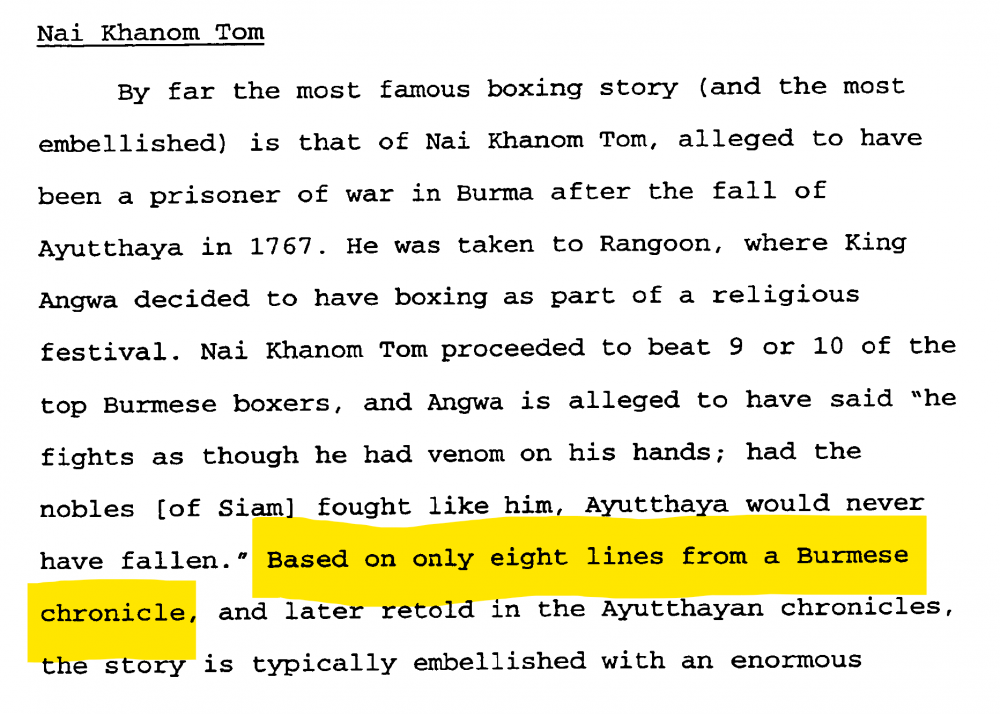

On 5/9/2021 at 9:25 PM, MuayThaiHistory said:

Yeah, I hope I can find it. I think I will contact Cornell University and ask if it is possible to obtain a copy of "Violence and Control: Social and Cultural Dimensions of Muay Thai Boxing (1998) ", because I saw they are one of the few universities with a copy in their library. Then it would be possible to obtain the source of the Nai Khanom Tom tale. If anyone can provide me with more information in the meantime, I would love to hear it.

I found Peter Vail's dissertation again. Unfortunately, he does not cite the Burmese Chronicle:

Vail repeats the omission in his article: MODERN "MUAI THAI" MYTHOLOGY.

-

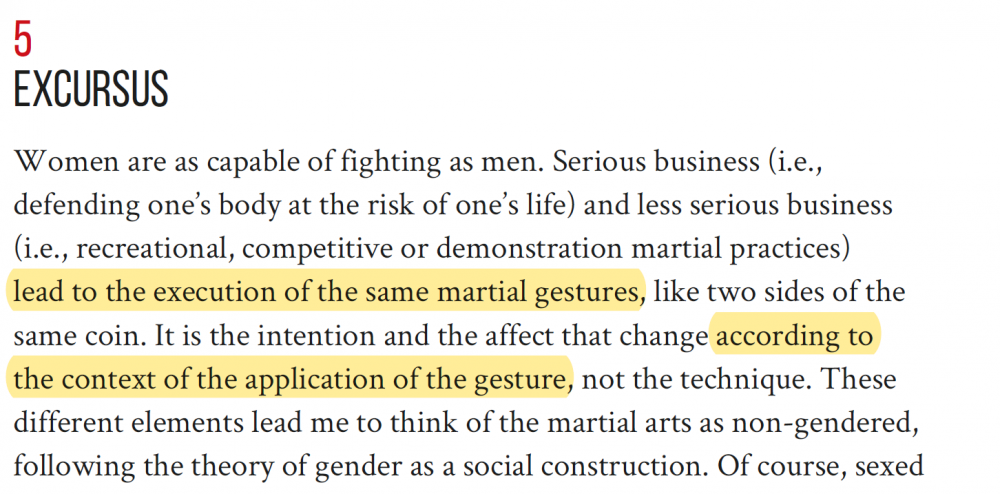

Seeing the Ungendered Body As Lines of Force

quoting to begin...

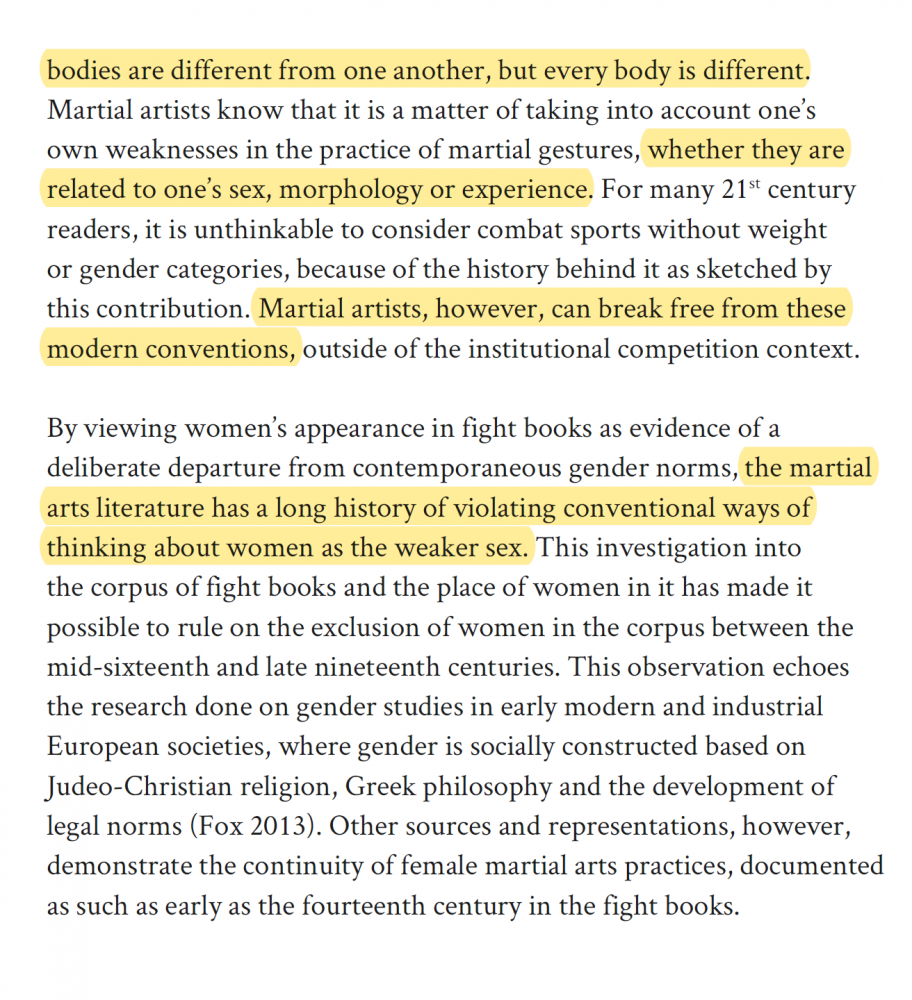

The above are the concluding thoughts of the excellent short article: Fight like a girl! An investigation into female martial practices in European Fight Books from the 14th to the 20th century by Daniel Jaquet. It presents in brief the basis of a coherent argument that though there are physiological differences between the sexes, distributed over a population, martial arts are about developing the advantages you can have that overcome any physical differences that might weigh against you. I present this argument about Muay Thai and women more at length in: The “Natural” Inferiority of Women and The Art of Muay Thai. Just as shorter fighters can fight (and beat) taller fighters, smaller fighters can beat heavier fighters and slower fighters can beat faster fighters, whatever projected or real physiological differences between women and men there may be, they can be overcome. That is the entire point of a fighting art, especially any art stemming from combat contexts. Interestingly enough, Daniel Jaquet actually points to modern "institutional competition" as over-informing the way we think about the capacities of a fighting female. We think in terms of classified differences (weight classes, and even rulesets, etc), and one of these classifications is simply gender.

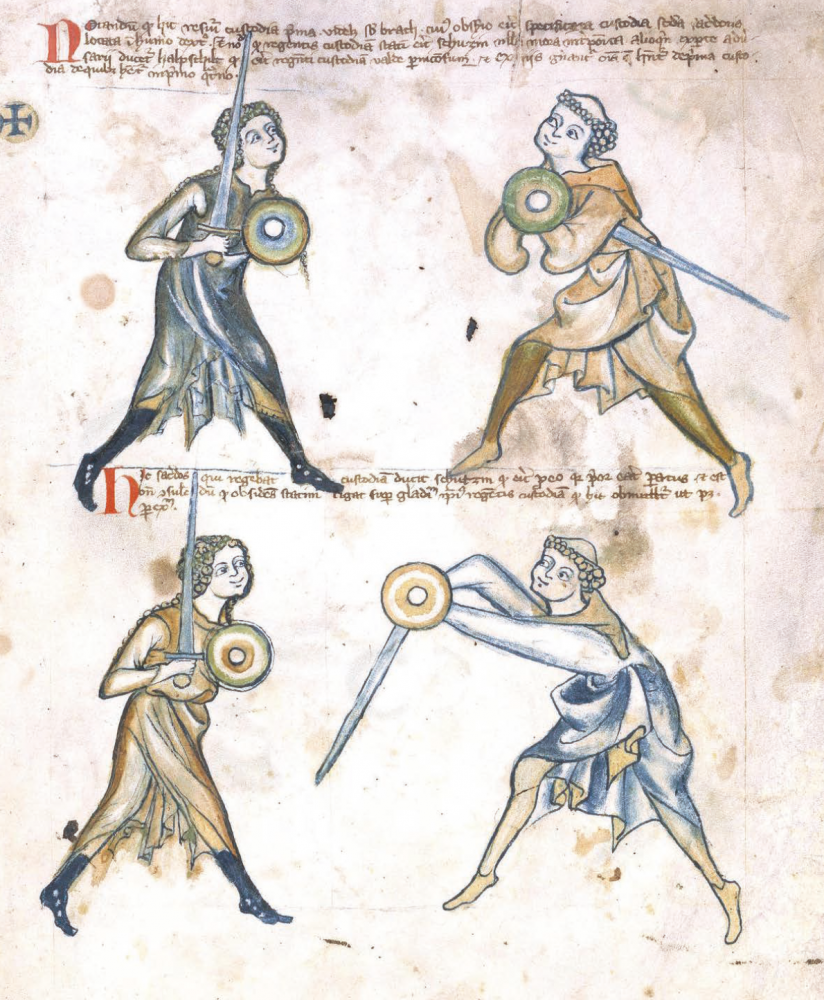

The article documents a conspicuous absence of women regarded as (possibly) equal combatants for nearly 700 years in combat literature, as gender became more codified in the European tradition. Jaquet marks a foothold in the timeline with this sword and shield technical manual in 1305 (Liber de arte dimicatoria), one of the last documentations of an assumed and illustrated gendered equivalence, at least for purposes of instruction.

There is a great deal to think about in this topic at large, but here I'm most interested in the effects modernization, or rationalization of a fighting art can lead to ideas of gender equality, under fighting arts. And some of the ways modernization can push against it was well. Jaquet's finishing remarks (above) speak to this basic, rationalizing idea. Bodies are all different, they are all capable of differing physical actions, amounts of force being applied, speed of reaction times, etc. It follows, just as physical weaponry like swords or shields are force amplifiers, so too are the analogical "weapons and shields" (techniques) when practiced in a fighting art. If you know how to throw (or slip) a punch, you are within a force amplifier. The rationalization of fighting arts is a modernizing concept of extracting aspects of a traditional process of embodied knowledge practice, and classifying it, for pedagogic reasons, analysis, or commercial use. Seeing gendered bodies as force equations is rationalization. If you follow my writings you know that I have a great deal of hesitance regarding the eroding forces involved in the rationalization of fighting arts, both in terms of teaching and commercial performance (we can lose valuable and hidden habitus as we re-contextualize practices), but this does not mean that I wholesale resist rationalization/modernization. Instead it can act as a scissor, weaving and unweaving as it goes. As Jaquet points out, modernization itself also brings forth conventions which can regard important, liberating rationalizations of a fighting art.

How Rationalized Jui-jitsu Changed the Early 20th Century Fight World

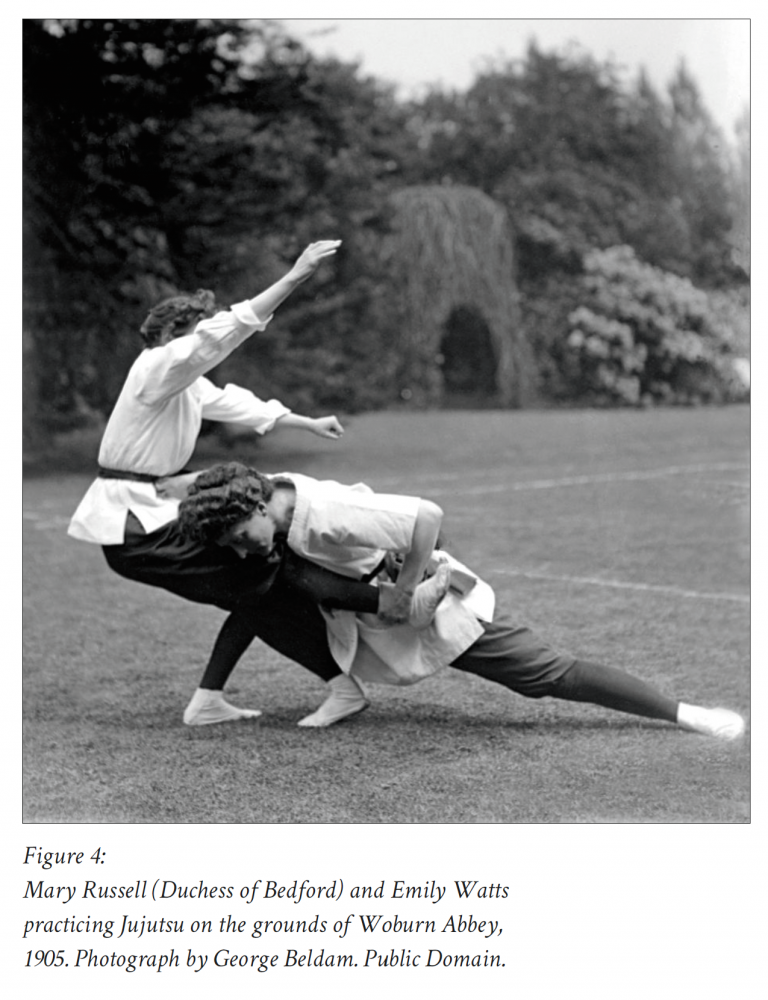

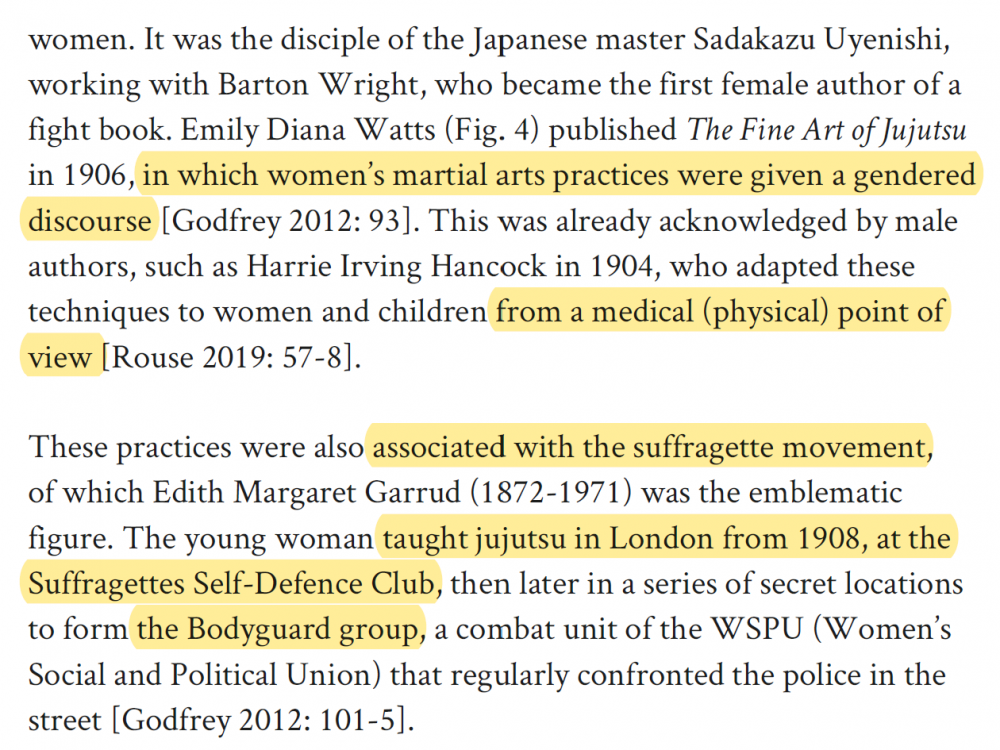

What I'm really interested in is something that Jaquet does not pursue, and it's something that I have only touched on in my reading. What follows therefore is going to be only a broad sketch of intuitions that would be interesting areas of study. I was particularly struck by this 1905 photo included in his article:

And the note tells us, this is the Duchess of Bedford training in Jiu-jitsu in England. I have not dug deeply into the history of Jiu-jitsu's immigration to England through Japanese masters, as well as other countries all over the world, but I assume this is part of a powerful rationalization impulse found in Japanese martial arts, much of it typified by Kanō Jigorō and his invention of Judo. Influenced by Western ideas of rational education and theories of utilitarianism Kano had the dream of modernizing traditional Jiu-jitsu along educational and health lines, and spreading this modernized version all over the world, eventually making it an Olympic sport.

Judo and other forms of modern-leaning Jiu-jitsu spread internationally at this time, and the Duchess of Bedford's Jiu-jitsu no doubt was a part of this diaspora of the fighting art. Famously, it reached all the way down to Brazil, eventually becoming today's Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, but at this time it it also reached Siam (Thailand). King Vajiravudh of Siam (reign 1910-1925) was actually raised and educated in England in his youth and young adulthood, for nearly a decade before taking the throne. He brought with him not only an appreciation for British Boxing (which would deeply shape the development of Siam's Muay Thai), but also, one might expect, Judo/Jiu-jitsu which had growing presence in Britain. In 1907, two years after the photo of Mary Russell the Japanese community in Bangkok is recorded as teaching Jui-jitsu, in 1912 Prince Wabulya returns from study abroad in London having learned Judo, and teaches it to enthusiasts and in 1919 Judo is taught at the very important Suan Kulap College, along side British Boxing and the newly named "Muay Thai". It is enough to say that the modernization of Muay Boran into Muay Thai in the 1920s, in the image of Western Boxing (at the time Siam is making efforts to appear civilized in the eyes of the West), was part of an even larger, in fact world wide rationalization effort lead by Judo/Jui-jitsu. When we see this photo of Mary Russell in England, this is part of the one-and-the-same British movements of influence that created modern Muay Thai over the next decades (gloved, weight class, fixed stadium, rounds). Rationalization is happening.

Notably, this unfolds it is in the context of King Chulalonkorn's previous religious reformation of Siam which would have lasting impact on the seats of Siam's Muay Thai, moving it away from temple teachings and magical practices. Siam is becoming a modern Nation, and the reformation of Buddhism (along with Muay Thai) is a significant part of that process:

Quote1902 – Religious Bangkok reforms outlawed non-Thammayut Buddhism mahanikai practices – these were often magical practices, but also boxing related activities were discouraged. It was a move towards orthodoxy that over decades would push muay teachings towards secular teaching (colleges, camps) and away from wat (temple) sources.

from The Modernization of Muay Thai – A Timeline

Returning to the rationalizing efforts of British Jui-jitsu which will almost necessarily un-moor rooted gender bias, with even political consequences. As Jaquet writes, the medical/physical perspective of empowerment and health ended up expressing itself in the Suffragettes Self-Defense Club, to aid in physical confrontations with police:

purportedly, the first photographically documented female fight in Siam (1929) image here

Women would be granted the right to vote in Thailand in 1932 (the first of Asia's countries, not far behind the UK's 1918. But, this rationalizing equality would not progress. In fact Siam/Thailand over the next decades would become busy "civilizing" itself in the eyes of the West by importing the strong Victorian-inspired views of powerful visual differences between genders. Modes of dress, differentiating the sexes, were even at one point legally mandated by the government in the 1940s. What we today read as quintessentially "Thai" traditional attitudes towards the differences between the sexes though complex is actually, perhaps best explained as a Western value and practice importation during the first half of the 20th century.

The visual differentiation of the sexes in dress: Thai cultural mandate #10 (1941): Polite international-style attire

Civilizing the Savage and Savagizing the Civil

What I'm interested in is the connection between the early 20th century rationalization/modernization of Jui-Juitsu in Britain, and today's rationalization-modernization of Muay Thai in Thailand. The schism between Thailand and Britain in terms of gender, under the guise of "civilization" recently and long last was symbolically bridged when women were finally integrated into Lumpinee Stadium promotion: The First Female Fight In Lumpinee Stadium Breaking the Prohibition. Note: the strong division between the genders of the late 1930s and 1940s in the "international-style" of work and dress is also in the context of the construction of Rajadamnern Stadium (1945) and Lumpinee Stadium (1956) under Thai fascism and Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (Prime Minister 1938-1944 and 1948-1957). It is unknown what gendered Muay Thai practices may have developed without this heritage of an imitation of the West. As an contemporary outsider we tend to assume these "traditional" gendered differences as purely and essentially "Thai" and not a product of Western example or influence.

Seeing these two photos, well over 100 years apart, in relationship to each other under the view of Internationalized Rationalization of fighting arts is fecund to examination. There is no clean line that leads between rationalization of the art and sport and the equality of the genders. Importantly, and not without irony, when King Vajiravudh modernized Muay Boran in imitation of British Boxing he was attempting to purge Siam and its fighting art of the impression of savageness. Contestants did die in the Kard Chuek ring (probably rarely) with rope-bound hands, but more importantly the use of feet and elbows of Siamese fighting was seen as primitive by British report. Codifying Muay Thai in the 1920s was no simple desire to just imitate the West as superior, as the West used the motive of civilizing "primitive" people to justify the colonization of peoples, including all the countries in Siam's orbit. No doubt King Vajiravudh had adopted many British aesthetics during his decade in British schooling, but there also something prophylactic to the transformation of Muay Thai before the eyes in the West.

Now though, with some irony, Thailand is bending its fighting art to the Internationalist tastes of greater violence, more aggression, as part of a vision that is pushing it to join what might be seen as a globalized Combat Sports Industrial Complex, battling for eyeballs. And, as I say ironically enough, with this comes the rising commercial viability of women seen as equals. As Lumpinee Stadium seeks to Internationalize itself it brings in women, and also it brings in the "savagery" for which Siam's fighting was (politically and colonially) stigmatized over 100 years ago, as MMA comes to its storied name. The "Be more civilized!" and "Distinguish the genders!" that was once demanded by the colonizing West has become "Be more violent!" and "Equalize the genders!" by the globalizing West...a globalization that is actually now an Internationalist vision.

What is missing from this story perhaps is the equivalence of Britain's Suffragettes Self-Defense Club, which is to say the way in which equality under a martial arts rationalization is connected to a broader political fight for women's equalities. From my view I suspect that the growing importance of respected female fighting in combat sports is an expression of the increased social and economic capital women have come to have in a globalized world. Women as having real and imagined physical prowess in the traditionally male-coded ring (and cage) symbolically manifests actual changes in female powers in society. Women in rings has grown out of the Suffragettes Self-Defense Club, not now equalizing themselves with embodied knowledge in the streets against police, but rather signifying their political and socio-economic heft to a globalized world. Yet, as all things bend back, the commercialized capture of symbolized female power in the ring is part of its re-domestication, as women's bodies become sites of judgement and eroticized re-packaging, problemizing any overriding narrative of liberty. As women are called to the ring under the auspices of aggression-first promotional fight theater in the double-bind navigation of globalized freedoms, the role of rationalization remains circumspect. Rationalization can and does lead to the re-codification of the genders, as we see with the conventions of institutional competition, as well as within the commodification of the female person and body by combat sport entertainment, yet it also holds the power to un-moor entrenched sexism and bias which work to restrict the possibilities of women as fighter who stands as proxy to the power of women in general.

-

1

1

-

-

A worthwhile gym to look at is Fight House in Singburi, where Kru Diesel has taken up shop after years of running FA Group. One of the best Muay Khao krus in Thailand. I don't know their roster right now, but he's a great trainer and sending Thai fighters to stadium fights.

-

1

1

-

-

8 hours ago, SLC said:

@Kevin - a follow-up question for you is once we find a gym we like should we book a longer stay or use our first four weeks to try many gyms? Would it be foolish in your opinion to spend time in 2 different areas of Thailand?

Hmmm. I guess this depends on how old your son is [edit in: sorry, I missed that he was 14], and more about your own tolerance, or enjoyment of change is. Me? I like to settle down in a place. It is only after 3 days or more that I feel ok. When I know where I'm eating, the way to the gym, etc. Then maybe at 7-10 days do I really feel like I'm in something. It also depends on how heavily or often you want to train. Every day? Twice a day? Or taking days off?

Just giving you my own sense, I'd say two weeks minimum for a single gym experience, once you know you like it, which means once you start moving again the next stay will feel shortened. When we first came to Thailand we committed in advance to two experiences over I think 6 weeks. I really loved our stay in Chiang Mai at Lanna at the time. Then, perfectly happy, we went down to Bangkok and Sasiprapa. The Bangkok experience wasn't bad in anyway, but we actually wished we had just stayed in Chiang Mai. It was far less gritty, the gym experience was really nice. It wasn't the worst thing to push for two, but it wasn't ideal.

I would maybe make a first choice of location, and then a list of 3 gyms in that location. I'd go to each of them for a day and just feel what it is like and go by intuition. Can I picture myself here for 2 weeks? If you find a great one, one you really vibe on, then just stop there, no need to push for more. I'd give myself 10 days in that first choice gym. After about 7 of those days I'd reassessed. Do I want to change gyms? Or do I want to change cities? If you are really happy where you are, just stay. It's pretty easy, and not that expensive to just hop on a plane and be somewhere else if you suddenly get the urge to have a different experience. Don't pay for lots of days in advance, especially in the time of COVID when tourism is going to be down. Everyone will be glad to have you. Keep things flexible.

-

1

1

-

-

There are good reasons to think about Kru Manop's gym in Chiang Mai. The first is that he's just an excellent instructor, with lots of technical awareness that comes from working with westerners over many years, and a patience that is very high level. His teaching muay is very high level, as he was once Saenchai's padman, and spent several years at Yokkao in Bangkok. Also, he's had lots of experience recently training on western boy, who now fights in Thai stadia. The boy and his father, I believe, have been at the gym for a couple of years.

https://www.facebook.com/Manop-Gym-2127920037423064/photos/2431860120362386

If you want to experience a big, Muay Thai gym complex like something like Tiger on Phuket, this certainly isn't that. But, if you want to spend a lot of time in a small gym with a personal touch, its the first gym that comes to mind for me.

Chiang Mai is culturally slower and more conservative (traditional) than other parts tourist oriented parts of the country, and quite beautiful, the kind of city and surrounding region that seem perfect for a 4 week experience.

We shot this little short when visiting there a bit ago. Kru Manop is also in the Muay Thai Library if you want to see a couple of hours of training with him, privately:

#55 Manop Manop Gym - The Art of the Teep (90 min) watch it here

#85 Kru Manop Yuangyai 2 - The Art of the Sweep (57 min) watch it here

Once in Chiang Mai you could also check out Kru Thailand's gym, on the other side of the city. It would be more of an "authentic" gym in that he trains Thai boys to become stadium fighters. He too is a very good instructor. Their Facebook Page is here: https://www.facebook.com/Sit-Thailand-Muay-Thai-Gym-106840670828643/

They live stream their training often on Facebook, so you could get a sense of the atmosphere.

Ideally, I say to not book long stays around any one particular gym, but rather spend a couple of days in a gym just to see what it feels like.

-

Sometimes a fighting art can learn from the histories of other fighting arts, when contemplating what it means for it to be spread to countries non-native to its production. Muay Thai has lessons to learn from the Internationalization of TKD through the Olympics, as it reaches for Olympic status itself, involving important questions on the commercialization of the sport, the codification of its nature, and its marketing through children pedagogy. Muay Thai, which itself was modernized in Thailand in the 1920s, has much to learn from the rationalizing exportation of Judo, throughout the world at the same time, likely part of that same wave to educate and rationalize through a fighting art, or things to learn from how Okinawan Karate proliferated through its introduction to affluent Japanese university students. We learn when we look at the paths, patterns and market forces that have shaped other fighting arts and sports.

Its for that reason that the fate of Capoeira, as it spread over the world into cultures that were not of its own birth, holds an informing mirror of analysis. One of the great struggles of Thailand's Muay Thai is over how to preserve its own authenticity, and the rich character of it's knowledge, without losing essentially what it is, as it becomes transplanted in cultures which are not its own. How much of "Thailand", how much of the micro-economies and sub-practices, which create the habitus of Muay Thai, need to come with the art and sport, for it to remain its own? Or, is Muay Thai best thought of as a set of mechanics & moves that can be extracted from the place of its birth, more or less whole, preserving its essential efficacy, letting the cultural trappings fall away as a kind of dross? Can - and should - Muay Thai be mined?

Drawing from the article: Mexican capoeira is not diasporic! – On glocalization, migration and the North-South divideAuthor: David Sebastian Contreras Islas << download it here. I've also attached my highlighted version of the article: Mexican capoeira is not diasporic! – On glocalization, migration and the North-South divide.pdf

The article's great. In its early history Capoeria provides compelling parallels to Thailand's Muay Thai, in that it too has had an schizophrenic authenticity tension, between provincial or at least marginal origins with low associations with crime or vice, and a more proper, more artful expression driven by social elites. Capoeira went through this 100 years ago, Thailand's Muay Thai still operates according to this tension, a tension which helps make up much of its identity in Thailand.

These evolutuions of acceptability in fighting arts are important tellings in the history of a fighting art, and because Thailand's Muay Thai never passed into an "academy" stage, but rather maintained its ideological tension between provincial "commoner" Muay Thai (the muay of the North, Isaan and the South), and cosmopolitan, royal-patronage Bangkok Muay Thai, a tension that has been wrestled out in actual full contact rings for more than the last century, fighting efficacy has proved more salient than in Capoeira. But, what Capoeira does draw forward is that a fighting art can pull with it, perhaps even necessarily pulls with it, its cultural milieu, the material origins of its creation, and that struggles over authenticity become important ones in the globalized marketplace. What is important is that these struggles over origin and authenticity exist all the way back into the roots of the fighting itself, and in some respects the fighting itself is about these roots. While Capoeria's authenticity battles to some degree are resolved by displayed skills in the ring (ruga) - the author argues that Mexican masters prove their authenticity by being able to hold their own against Brazilian masters - Muay Thai authenticity battles are across 1,000s of rings, a laboratory of efficacy and cultural relevance.

The widest import of the article is on the differences between Globalized diaspora - the way that Capoeira has spread to Western countries like the United Kingdom, through the diaspora of Brazilians themselves, a function of the economic connectivity between nations, and what he takes to be the Glocalized spread of Capoeria to less economically advantageous countries like Mexico. The tension here is between Brazilians who necessarily bring much of the culture of Brazil with them, as they teach Capoeira, much of its habitus, and cross-cultural examples such as Mexico, where no Brazilian masters have settled, but where Capoeira has grown through Mexican masters...who may, or may not make pilgrimages to Brazil itself, in bids for authenticity.

One cannot help but see some parallels between the desire for, or at least pressure for, Western Muay Thai teachers to found themselves on some Thailand experiences in order to authenticate their teachings. In Western marketplaces like America there can be intense struggle over these questions of authenticity, which gyms have coaching trees tracing back to Thailand, or even have ex-Thai fighters, and which gyms approach Muay Thai perhaps as a study and promulgation of efficacy itself. In a world where MMA also exerts a kind of democratizing force upon martial arts of all kinds, and where digital access to very rich Thai knowledge archives, like our Muay Thai Library project, this struggle over authenticity becomes quite complex.

Market vs Ring

One of the most import distinctions in the questions of authenticity and glocalization between Brazil's Capoeira and Thailand's Muay Thai, especially under the glocalization perspective, is that the "authenticity" of Thailand's Muay Thai, unlikely that of Capoeira, has a foundational dimension of assumed efficacy in the ring. Which is to say, the cultural signatures of authenticity that surround a fighting art, like that of Muay Thai, involve the notion that authentic means efficacious. And disputes of authenticity away from the home country, in Muay Thai, also have to be disputes over fighting efficacy. Yes, the author does say that Mexican masters of Capoeira have to prove their capacities vs other Brazilian masters, in the "game" of Capoeira, but because Thailand's Muay Thai (and many of its cultural trappings/habitus) come out of the laboratory of 1,000s of fighting ring events, like for instance the art of western boxing, there is an assumed real relationship between cultural realness and fighting capacity. An example of glocalization taken up in the article is how Hip Hop traveled the world but became localized, as the music of Hip Hop came to express local circumstances, and be sung in local languages. Germany developed a "German" Hip Hop. Mexico, a "Mexican" Hip Hop. The phenomena of Hip Hop is found all over the world, but it is glocalized by different people. Hip Hop on the other hand, does not have a straight forward efficacy dimension to its expressive art. Western glocalized Muay Thai expressions, especially those which depart of Thailand coaching trees, and cultural habitus, do make arguments towards their own efficacies, perhaps merging "Thai techniques" with combination training, or borrowings from other fighting arts, under the claim that they are making a potent fighting approach. But, these are largely marketing claims. Which is to say positioning oneself in a market milieu. In the rings of Thailand, under the aesethetics of Thai fighting, there is. broadly, only one "authentic" efficacy -- itself splintered across the country in innumerable in-culture approaches: Muay Thai developed under the cultural habitus of Thailand. Muay Thai is not Hip Hop...but, it does have character and qualities that it shares with Hip Hop, and Capoeira, as it expresses artfully the culture from which it came, carrying an ethos with it. You can read more on the habitus of Thailand's Muay Thai here: Trans-Freedoms Through Authentic Muay Thai Training in Thailand Understood Through Bourdieu's Habitus, Doxa and Hexis

Globalization and Glocalization

There is another distinction worth carrying forward when thinking about glocalization. In the article it is used generally to describe somewhat favorable artistic particularizations of a world-wide art, adopted by a community. The glocalization process is seen as one of enrichment. David Sebastian Contreras Islas describes how traditional song might be translated into a new native tongue, or even how native expressions may mimic the original intent of practices, but in new way. To take a small, yet layered example perhaps, in Muay Thai one finds gyms in the West practicing the Japanese Karate "Ous" in groups, as a sign of respect, in Muay Thai contexts, not really something that reflects Muay Thai practice at all, but rather mimes Western practices of "Martial Arts culture". This is to say, there is a necessary translation of arts into new culture, while still hoping to preserve the conditions and practices that worked to create it, to some degree. There is a kind of artistic tug-of-war which possibly produces enrichment but also degradation.

But, there is an older, and perhaps far more salient meaning to Glocalization, which brings to mind International brands like Coca-Cola and McDonald's. The term was created to describe the ways that globalizing brands can penetrate new, culturally diverse markets. Sometimes this meant changing the taglines of brands, or brand associations. Sometimes recipes of fast foods need to be altered to fight a local palate. In fact there are any number of ways that global brands have learned to particularize themselves to fit into local contexts...to penetrate the market. One of the benefits of the glocalization concept is to help see how globalizing forces - forces that many have argued work to homogenize, to monocrop - actually use practices of particularization to take foothold in local contexts. It looks and feels local, but there is a globalizing force, and organization and ethos of homogeneity, working behind those individual tailorings. Of course digital media has taken this well beyond the level of the community, where globalization becomes glocalized in highly individualized news feeds and product exposures, made not only for your sub-set, but for you. Celebrating glocalization, and its enrichment, can give us to miss the globalizing forces (and intents) behind those particularities.

So from my perspective the article on Caipoeira has at least two aspects of importance for Thailand's Muay Thai, as it spreads to countries and cultures around the world. The first is that it brings forward the very real and sometimes painful struggle for authenticity of a practice outside the homeland of its origin. This is something that plays out in a marketplace, carrying with it a burden of fighting efficacy, but...also, these new adaptations of the art have the potential for glocalized enrichment, cultural inventions of, or re-inventions of the art in a new land. The second aspect though points to the globalizing practices that involve the spread of the art and sport, which may hide behind glocalized individuation. These forces tend to push towards a homogenization and the erasure of the living signatures of the origin of Muay Thai. The uniqueness of the sport and art intentionally become sanded down to remove any friction between cultures. In the name of an ease of comprehension or consumption the richness and variation of origin can become effaced. We see these trends in globalizing brands of Thailand's Muay Thai in IFMA amateur and Olympic aims, or instance, or ONE Championship's commercial fighting, each of which has worked it its own way to smooth out the differences of Thailand's Muay Thai so that it can more frictionlessly slip into other cultures and their consumption - not to mention changes in practice within the Thailand itself, designed to appeal to Internationalized & tourist-oriented tastes. Turning Muay Thai into a kind of "kickboxing" (which it definitionally is not), modifying rules and scoring so as to no longer reflect Thai cultural strengths and qualities, so that it can be to some degree monocropped in a variety of climates and soils, brings with it danger...the danger of effacing the differences of origin so much that those differences erode in the country of origin itself, such that it may no longer be able to produce Muay Thai as it has been historically known. These homogenizing trends can lurk behind legitimate and sometimes enriching glocalized struggles for authenticity, as David Sebastian Contreras Islas describes.

-

This very interesting description of how the legalization of Caipoeira in Brazil was linked the teaching of the art to the more affluent, turning into a "Martial Art" in the Asian model. This is roughly the same 1920s-1930s time frame when Okinawa Karate was first taught to affluent university students in Japan. Even at the time, there was a strong cultural identity issue at play, notably among Brazilian intellectuals:

-

A really great article that pulls so much together on the events surrounding the opening of Lumpinee Stadium to women, read Emma's:

The First Women’s Fights at Lumpini: How We Got Here and What’s Next

-

1

1

-

-

This is a really difficult question. On one level it is easy to answer: Yes you need a good coach for self-correction and guidance...but, you can also probably get a lot more out of self-training and video study than many people think. The reason for the coach...and honestly, it's more than a coach, it's an entire team of people you can spar with, experiment with, grow with, is that its extremely hard to self-correct. It's like tickling yourself. You can "kinda" do it, but it really is the intersubjectivity that creates the growth, and the real-world sparring that lets your body figure things out. Otherwise, it can be something like learning to surf, but not going into the water much.

On the other hand, things like Sylvie's Muay Thai Library project are kind of incredible. These are real life training sessions with some of the greatest fighters and krus on the planet, krus well beyond pretty much anyone you'd run into in a typical gym. So the knowledge and lessons in these are off the charts. It is possible to kind of prime yourself for when you eventually do go to a coach or a team, taking to heart the experiences in those videos.

Another thing you can do, by yourself, is lots and lots of shadowboxing, in the method Yodkhunpon teaches. He molded himself with very little training equipment and little coaching, at least early on, through rigorous, lengthy shadow boxing. You can see some of that here:

The above is part of a full length 1 hour study of Yodkhunpon's shadowboxing philosophy in the Muay Thai Library. In it there is discussion of how he felt like his shadowboxing really primed him for high-level fighting in Bangkok. There is NO substitute for a team of co-fighters and coach, but there are lots of things that you can do to build out a scaffolding which later can make teamwork better.

Sometimes there are very good reasons why someone doesn't have a coach. Maybe its where they live. Or, the coach that is available isn't a very good coach, or someone who is helpful. A bad coach can be worse than no coach. Or, there just is no money for a coach right now. It doesn't mean that growth has to stop. There are always ways forward.

-

1

1

-

-

In a bit of history, Sylvie reported on the early MMA scene in Thailand way back in 2016 when ONE Championship put on a combination MMA and rock concert event in Bangkok. At the time MMA was, I believe, illegal in the country as it was seen as a threat to Muay Thai heritage, but Chatri and ONE managed to get an exception (or even change the law, I'm not sure). Sylvie's article including an interview with a Thai MMA fighter who was working his way through the very early scene. Some are pointing out that the new announcements regarding New New Lumpinee includes Lumpinee concerts. Perhaps they are thinking of doing similar concert + combat sport events. Read the article here: Insight into Thailand’s MMA Scene – Interview with MMA Fighter Itti Chantrakoon

You can see Sylvie's 2016 interview with one of Thailand's proto-MMA fighters here:

-

1

1

-

-

I understand that we are talking about broadening the scope of viewership, and even the very identity of Thailand's Muay Thai. One can never really be sure if something new is coming to save, or destroy something old or traditional that is waning. I really believe that, but we do need to keep track of where this is going.

It's worth noting that Fairtex Pattaya also hosted something called Fight Circus, a bunch of oddity fights November 6th, streamed to the adult cam site Camsoda, and tweeted out in parts. You can read about this show, and see more event examples here Bloody Elbow: Fight Circus 3 videos: Watch insane ‘Siamese kickboxing,’ literal phone booth fighting, more oddities. Pretty incredibly Australian Muay Thai fighter Celest Hansen fought a Phone Booth "Leithwei" fight, streamed 8 days before she became part of the first female bout to fight in the Lumpinee Stadium ring, a huge historic moment in the Muay Thai Thailand. It's highly unlikely that this Phone Booth fight was filmed when streamed, so near the Lumpinee fight, as Celest is cut in the video. It was probably just fed into the Nov 6th stream as if live, or tweeted it out then; who can tell. Celest lives in Phuket, not Pattaya, and again this was only 8 days before she entered the ring at Lumpinee Stadium. But, in the context of changes coming to Thailand's Muay Thai the juxtaposition of the two fights in time is striking.

Here is "Siamese Kickboxing" tweeted out from the oddities show.

Here Celest is coming out of the Lumpinee ring 8 days after the stream, making huge history, photo series here:

You can see Celest fighting the historic fight at Lumpinee on November 13th here [full fight]:

The fight oddities streaming show was put on, separately, at Faritex many hours before another historic fight in the evening, also hosted at Fairtex: the WBC World Championship between Souris Manfredi and Dangkongfah. This epic fight marked the first time the new WBC female Muay Thai rankings resulted in a Westerner vs Thai World Championship, which you can see here. In the day fight oddities, in the evening a big WBC female title fight:

Aside from the sheer toughness and badassness of Celest being in both of these events, it also provides a jarring snapshot into just how far we can be stretching the tradition <<<>>>new eyeballs spectrum. MMA isn't even the full limit of "extreme" in that reach. And also it brings into view the unique place female fighters find themselves within it. Female fighting, as legitimate, became internationally stamped as legitimate through MMA,, and the transformations that Ronda Rousey forced open in the UFC. Then headlining female fights were embraced by ONE Championship, in some imitation of the UFC, and then by Fairtex itself who set upon creating a female MMA fight team - one of the first in Thailand to do so - starting with Stamp Fairtex. Female fighters in a certain respect represent, or even embody the possibility of new, modern fighting. But as in this case, with commericialization and the need to reach new audiences, one also risks farce and even circus. This occurs just as when female fighters themselves yearn for and reach to be integrated in the traditions and honor of Lumpinee which has excluded them. What does it mean for MMA to be included in Lumpinee? It's a really interesting question with no simple answer.

-

2

2

-

-

On the Pedagogy of Thai Padwork

The Fighting Scholars anthology cited above carries with it that demand that theory accommodate conscious experiences in practiced skill acquisition, because they speak to training milieu. Ideally, theory and description would take us all the way down, from the most conscious practices and overt skills, into the roots of an art, practice, sport and culture, the unconscious qualities of bodily disposition. In that view, one of the more rich, regular examples of skill acquisition is Thai style padwork. While in the West padwork often is the occasion for the training of combinations, in Thailand padwork is much more about discovery of positions and tempos, wordlessly directed through the padman as he frames, changes aspect, pressures, pivots and tempos. The best padmen actually mimetically sculpt a fighter along the lines of a style, pulling forth qualities that cannot be effectively described, or even mechanically directed for imitation. Instead, it becomes a symbiotic intersubjectivity which creates possibilities and subtitles, and...importantly, invites the fighter themselves to create spatio-temporal solutions to constantly posed puzzles and problems. This is the vital uniqueness of Thailand's padwork. Because padmen are often retired prolific stadia fighters themselves they are communicating their own bodily knowledge, their own inscriptions, gained not only through their ring fights, but also their own pedagogy experiences since early youth. They are not teaching mechanics so much as an undermusic. In the kaimuay they aren't even really teaching at all, consciously. Padwork traditionally was a way of simulating fighting energies, and as Kaensak told us, "charging the battery" before fights. It has evolved since the traditional kaimuay into a more guided experience because of the influence of Western students who are more in need of instruction, but with a good padman it still is not the transfer of mechanical instruction. It's a pulling of qualities of style and efficacy, especially in terms of a stylistic musicality. Padwork presents a specific case-study which stretches below the threshold of the conscious and the rational. This is where Bourdieu's concept of habitus fills in many of the unseen holes in what Thai padwork is communicating and creating.

Three Video Examples

I present three videos below, for example. The first is with the yodmuay legend of the sport Attachai. The reason this is a great example is that he's "teaching" his stylistics (fight preferences) to Sylvie who he has never trained with before. Because they do not know each other, in the example you can see through the dis-junction of unfamiliarity where he is leading. Padwork is most deeply unconscious fomulation when the padman and fighter know each other well. Then the under-patterns, which have become much more ingrained as pathways, and the fighter's own creative positional solutions have entered into an extensive dialogue.

The second video is an hour long discussion of Sylvie's padwork with Pi Nu from 2017. They know each other with great familiarity. She describes the various intersubjective tactics Pi Nu uses to draw out qualities and technicalities in her strikes and positions, ultimately a music of muay.

The third video is an extreme slow motion film of padwork with Pi Nu from 2019. Padwork is usually done in the context of the rest of the kaimuay, the fighting Thai boys, but in this case it was with the winding down gym. What one can feel in the film are all the ways that padwork between a trainer and a student/fighter is connected invisibly to all of the social space in the gym, and many of the unconscious or semi-conscious intersubjective play of looks, pauses and postures also become more apparent. These 3 videos are part of the vast ethnography that Sylvie has created, in documenting the Muay of Thailand. At bottom is a link to a thorough 1 hr discussion of the padwork of Chatchanoi, who she feels is the best padman in Thailand.

The Chatchanoi session for patrons sketches out in some detail the building of an initial vocabulary of one of the best padman in all of Thailand. It's great documentation of what padwork can be, as it seeks to build a style: watch it here

-

5 hours ago, Richard Weston said:

Gambling and Thailand are one in the same

This really is so. The bold experiment is going to come up against some very intractable aspects of the sport and culture...or it's Muay Thai is going to become so radically changed, one would have to question if it is still the Muay Thai of Thailand. I'm pretty interested in just how they are going to try and walk this line.

Admittedly, the problem probably isn't gambling per se, but very powerful gamblers who can shift and set odds, and basically call-in a win or a loss. When wins and losses start to just become manipulated, then the fabric of what sport is starts to tear and fray.

-

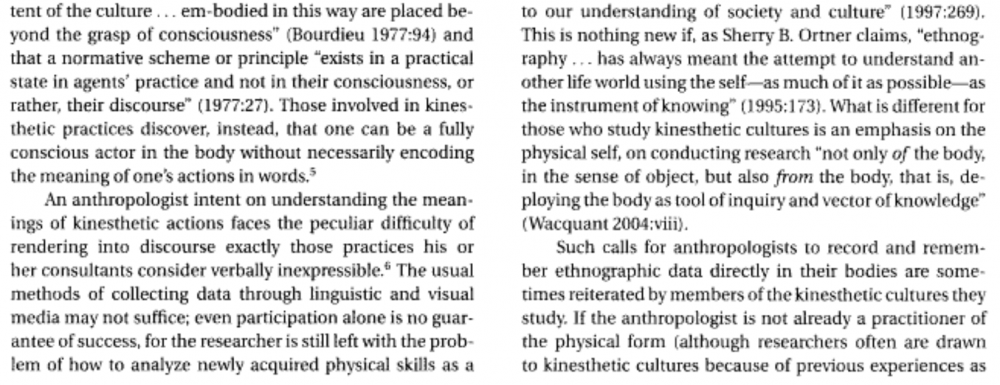

Thick Participation

Memory in Our Body: Thick Participation and the Translation of Kinesthetic Experienceby Jaida Kim Samudra (The JSTOR Google sign-in allows 100 online articles read per month)This essay which presents the concept of Thick Participation is a seminal one in the discussion of embodied knowledge. One of the early pages of the essay. Note, one of the aspects of contention is Bourdieu's insistence upon unconscious knowledge as the basis of the habitus. Those who study practiced arts, like combat sports, or dance, find it important to make room for practiced, but yet non-verbal knowledge. One can definitely see the value of those kinds of conscious-but-non-verbal awarenesses and practices, but in terms of deeper meanings, its the unconscious elements that are rooted beneath those practices that may carry the weight of what an art is:

In its discussion of Silat it picks upon the role of confusion, the lack of verbal answers given, and the need to experience and explore the answer. Methodical, rational "counter" teaching in the West often elides this method of discovery:

I wrote about this "not being given the answer" aspect of kaimuay learning in Thailand, discussing the benefits Sylvie experienced over many, many months, under a very difficult lock being done to her...until she eventually started inventing solves:

-

Here is the entire "White Men Don't Flow" article in video scroll. I was pretty surprised by the kaimuay Muay Thai relevance of the ethnographer's perspective, on a fighting art that may not be widely embraced as efficacious or even authentic, perhaps complicated by the public YouTube popularity of it. I put it here for you to decide for yourself. I also really enjoyed its incredible variety of influences, its meaning & lore and assorted veracities.

-

-

-

This quotation from "White Men Don't Flow: Embodied Aesthetics of the 52 Hand Blocks" of the Fighting Scholars anthology has a really good description of the embodiment of techniques at the emotional/affective level, something Sylvie's talked a great deal of. 52 Blocks has a kind of Internet disdain as a fake fighting style, but it makes a great case history because its influences, practices and pedagogies are so incredibly eclectic. It's very hard to pair away the "boxing" influence from the 1970s Hong Kong Kung Fu movie influence, because its a bricolage art deeply buried in a subculture. This makes a sociological study of it of some interest, because categories of description have to flow over a varied landscape.

This description of a student, the author, not taking the right affective disposition in learning a technique is actually quite close to something Sylvie has repeatedly insisted upon when documenting the muay of legends of the Thai ring. Each legend has his own affective disposition which is expressed through his muay, itself an individuation, and sometimes an amalgum of, larger Muay Thai fight styles, which hold their own aesthetics. In this example, from 52 Blocks, the author/student does not have enough disdain. The affects and habitus patterns which ground a great fighter's style in Thailand, which animate it and make it do what it does, have to be inhabited, in order to understand (and execute) the techniques within. You cannot have Karuhat's "kick" without something of Karuhat's aloof, floating, artful grace, affectively. It comes out of that affective matrix. Sylvie insists that in learning the muay of legends, it is best to actually impersonate them, everything about them. How they talk, stand, walk. Be them. These are embodied techniques.

This goes against the grain of much of the rationalized, mechanical abstraction Thailand's fighting techniques, mining them from not only the fighters who expressed them in the ring, but also the micro-cultures and conditions which bore them. The rational mind seeks to just harvest the "efficacy", often, without the affective truth which holds that efficacy together. Techniques can become modular, mechanical plug-and-plays in a constructed fighting apparatus, placed into an assembly line of students.

In this slow motion treatment of the very famous padwork video of Dieselnoi, at the peak of his greatness, you can feel the disdain (or some related, relentless affect) which is necessary for the technique of his knees. They are not separable.

The article on 52 Blocks also draws elements of importance from posture and symbolic signaling, and also the specific rhythms of fighting, both things can be hidden or hard to learn aspects of Thailand's kaimuay Muay Thai. I was somewhat surprised by how much of the ethnographer's conclusion could map onto Western attempts to learn the kaimuay Muay Thai of Thailand:

-

Two Published Resources on Habitus and Fighting Arts

Searching around there actually is a "embodied knowledge" approach to fighting sports and martial arts that I was not aware of. It largely stems from the work of Wacquant and boxing:

Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer by Loic Wacquant

"When French sociologist Loic Wacquant signed up at a boxing gym in a black neighborhood of Chicago's South Side, he had never contemplated getting close to a ring, let alone climbing into it. Yet for three years he immersed himself among local fighters, amateur and professional. He learned the Sweet science of bruising, participating in all phases of the pugilist's strenuous preparation, from shadow-boxing drills to sparring to fighting in the Golden Gloves tournament. In this experimental ethnography of incandescent intensity, the scholar-turned-boxer supplies a model for a "carnal sociology" capable of capturing "the taste and ache of action." Body & Soul marries the analytic rigor of the sociologist with the stylistic grace of the novelist to offer a compelling portrait of a bodily craft and of life and labor in the black American ghetto, but also a fascinating tale of personal transformation and social transcendence."Stemming from Wacquant's work is this anthology of the application of Bourdieu's concepts to martial and fighting arts:

Fighting Scholars: Habitus and Ethnographies of Martial Arts and Combat Sports Raúl Sánchez García (ed.), Dale C. Spenser (ed.)

‘Fighting Scholars’ offers the first book-length overview of the ethnographic study of martial arts and combat sports. The book’s main claim is that such activities represent privileged grounds to access different social dimensions, such as emotion, violence, pain, gender, ethnicity and religion. In order to explore these dimensions, the concept of ‘habitus’ is presented prominently as an epistemic remedy for the academic distant gaze of the effaced academic body. The book’s most innovative features are its empirical focus and theoretical orientation. While ethnographic research is a widespread and popular approach within the social sciences, combat sports and martial arts have yet to be sufficiently interrogated from an ethnographic standpoint. The different contributions of this volume are aligned within the same project that began to crystallize in Loïc Wacquant’s ‘Body and Soul’: the construction of a ‘carnal sociology’ that constitutes an exploration of the social world ‘from’ the body."My observations: To be honest, reading through this anthology I felt it was very uneven. I do understand that this is a nascent field of study, but some of these approaches seem to have two worlds to them. One is just the repetitious framing of the theoretical perspective, positioning the article within academic discourse, and in many times directly within Wacquant's work, and the other world can be rather banal "recording" of facts of training or transmission, in the role of ethnographic "notes" (being objective and science-ish). Inserted between these two worlds can be biographical descriptions of the author, which supposedly work to mediate between them. I've not completed the anthology yet, but the Muay Thai chapter was a specific disappointment, just mashing short term "field notes" with some Bourdieu sociology and a story of gym hopping. What seems lacking in some of these articles is insightful and inventive connection between the two worlds, sewing them richly together. I will say "The Teacher's Blessing and the Withheld Hand" on the South Indian martial art kalarippayattu in Chapter 8 was one of the stronger ones in terms of personal report around two vignettes, and "White Men Don't Flow: Embodied Aesthetics of the 52 Hand Blocks" has some very interesting points of observation which I quote from in posts below, mapping onto Thailand's kaimuay Muay Thai. And "Japanese Religions and Kyudo (Japanese Archery): An Anthropological Perspective" is philosophically expressive, melding practice/habitus to Deleuze's actual/virtual.For me a perhaps more intellectually robust anthology is Making Knowledge, exploring more of the connective tissue between theory and embodied practice, though with only one chapter on fighting arts (Capoeira):

-

Such an interesting political development in Muay Thai. Covid has put so much economic pressure on Muay Thai it has forced customary ways of doing business into new forms. Phuket kind of lost out its privileged position as THE fighter's destination, something they held a few years ago but seemed to lose out some of that to Chiang Mai in the North. With the sandbox advantage and the rise of Channel 8 fights on the island, it seems so smart to band together and make something of this momentum. Phuket seems poised to reach for something higher. I love that there is an interest in developing the kaimuay dimension of fighter production, and that 5 round fights are not just falling away to 3 round Entertainment Muay Thai.

-

This is Sylvie and my Muay Thai Bones podcast we recorded a few days before the historic event. We discuss in great detail all the circumstances we have led to the inclusion of women in this historic ring of Thailand:

One of the things we talk about in our podcast is that this fight was first scheduled as a 5 round fight, then with some disappointment changed to the 3 round fight. Amazingly, the Western fighter Celest did not even know until she came back to her corner after the 3rd round, thinking the fight was over, that it indeed once again it was changed back to a 5 round fight. Her Thai opponent also might not have known.

.thumb.jpg.3f2071842e33ba527b904a46d08f5366.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.5b2661c6373af5cb48784182cb59c38f.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.e2839e074849ccb0bd0c246f4a22b4a6.jpg)

Sylvie's Two Vlogs 11 Years Apart: The Drive to Expose Your Flaws To Everyone and the Heart of Muay Thai

in Open Topics - men and women - General Muay Thai Discussion and News

Posted

Two things may have persisted through all these years. Sylvie just has always patchworked her training approach. At the time of the the first video she's taking the train down from Fort Montgomery where we lived in a little rented house next to a National Park, to train in Manhattan. We were just piecing training together because there was no real path to where she wanted to get as a fighter, no "Point A to point B, just do all the work, listen to all the right people and you'll get there" path. 11 years on we are in the exact same place. There is no point A to point B path. She's much, much further down a path of her own invention, to be sure, tinkering steps forward up a rock wall, but everything unstable that she faced 11 years ago is still right there. She's training sometimes at her old gym, sometimes alone working on self-curation, daily in sparring at another gym, privately with Yodkhunpon, and all the intermittent training in filming legends and great krus in the Library. But, from at least my perception, nothing has changed at all in this. She is not being carried by a process, or by powerful others, and in this sense is exposed. There is no safe port. And because her process involves sharing her flaws with others - unlike every other fighter I've ever seen, where it is regular to hide your flaw and amplify your best qualities - this exposure is hard to carry. The other aspect that has persisted is that because she's a true disruptor in the sport, doing things outside of the expectations and ways of others who are invested quite differently, there is a constant social current she is swimming against. In the first video she's talking about YouTube criticism, but more this is just push back against who she is. So many have come to support her over the last decade, and lent their voices & resources to make the path possible, but still there is, and may always be a detractor audience, which in part comes from the fact that she's still doing things that nobody else does. In the second vlog she's matured into her place in the sport, taken root in herself...to some small degree, but personally the same pressures of resistance press upon her. The road is no easier at this point, than it was 11 years ago. In fact in many ways its even more difficult...but, what has changed and deepened is the richness of what she has built up inside, with 268 fights and a decade of sharing her flaws with others for over a decade. She has more substance and standing and belief in what she is doing. This is what I see.