-

Posts

2,264 -

Joined

-

Days Won

499

Posts posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

-

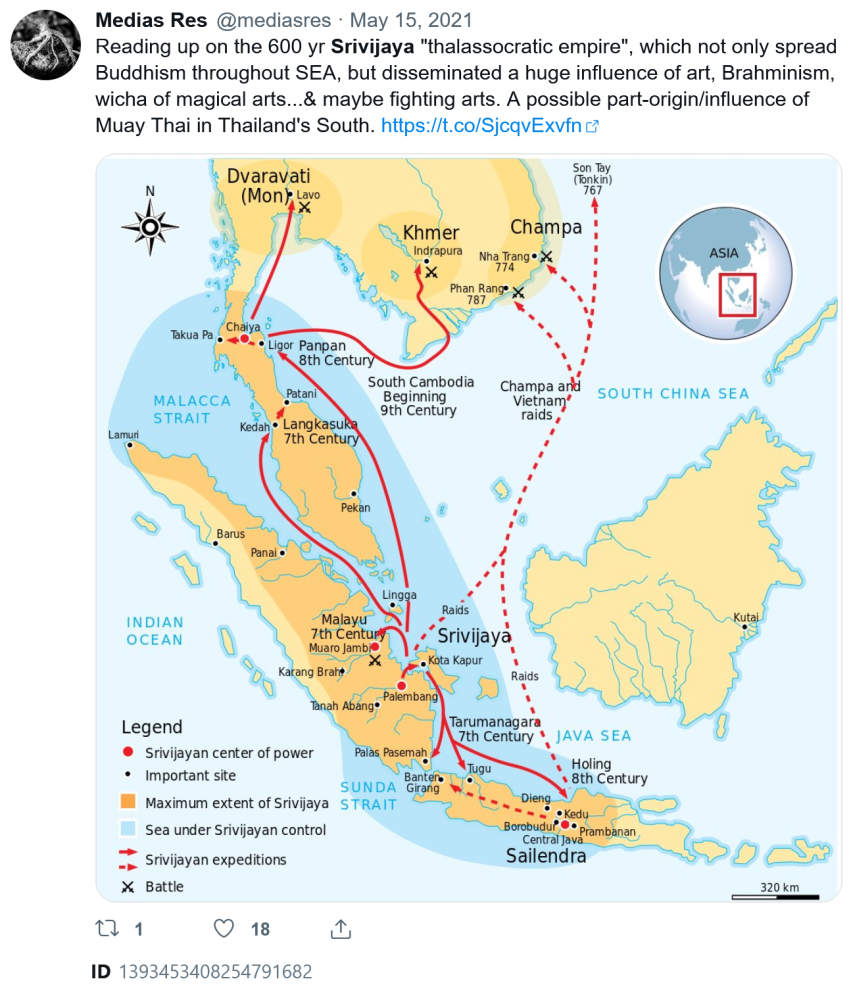

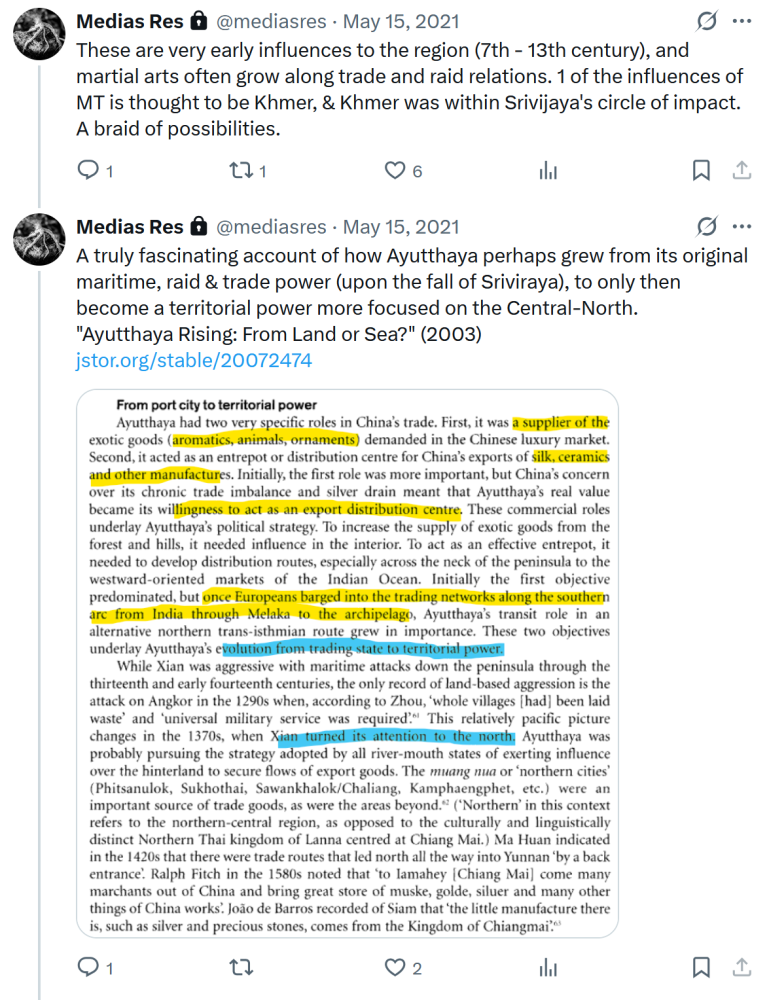

Speculatively, it seems likely that the real "warfare roots" of ring Muay Thai goes back to all the downtime during siege encampment, (and peacetime) Ayutthaya's across the river outer quarters. One of the earliest historical accounts of Siamese ring fighting is of the "Tiger King" disguising himself and participating in plebeian ring fighting. This is not "warfare fighting" and goes back several hundred years. One can imagine that such fighting would share some fighting principles with what occurred on the battlefield, but as it was unarmed and likely a gambling driven sport it - at least to me - likely seems like it has had its very own lineage of development. Less was the case that people were bringing battlefield lessons into the ring, and more that gambled on fighting skills developed ring-to-ring. In such cases of course, developing balance and defensive prowess would be important.

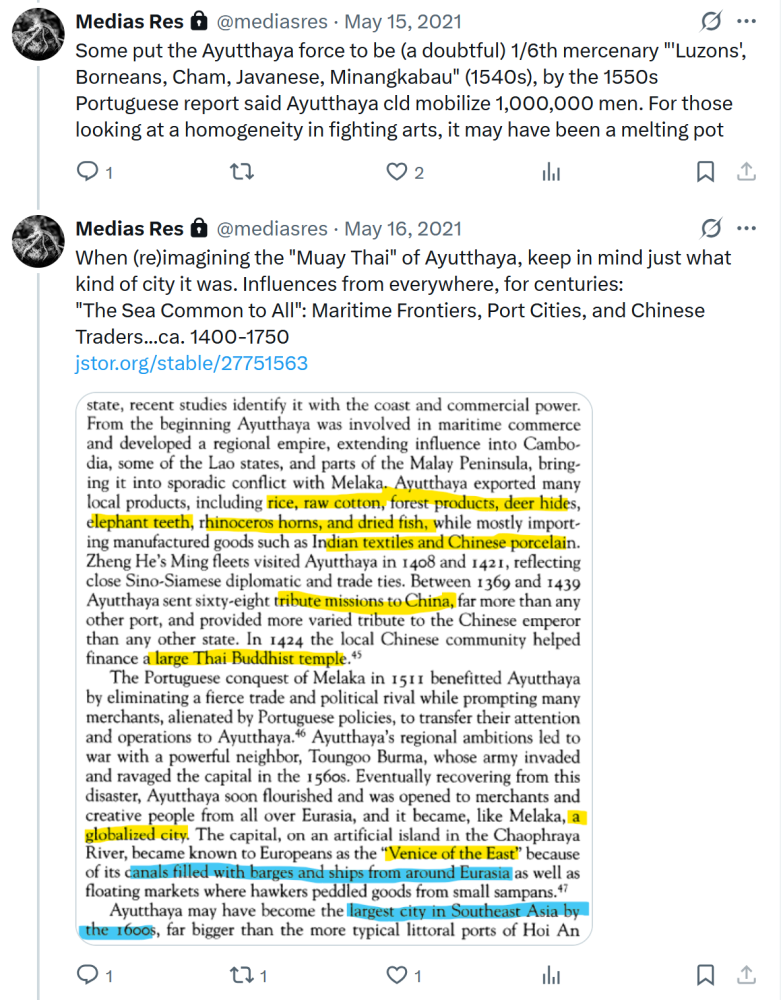

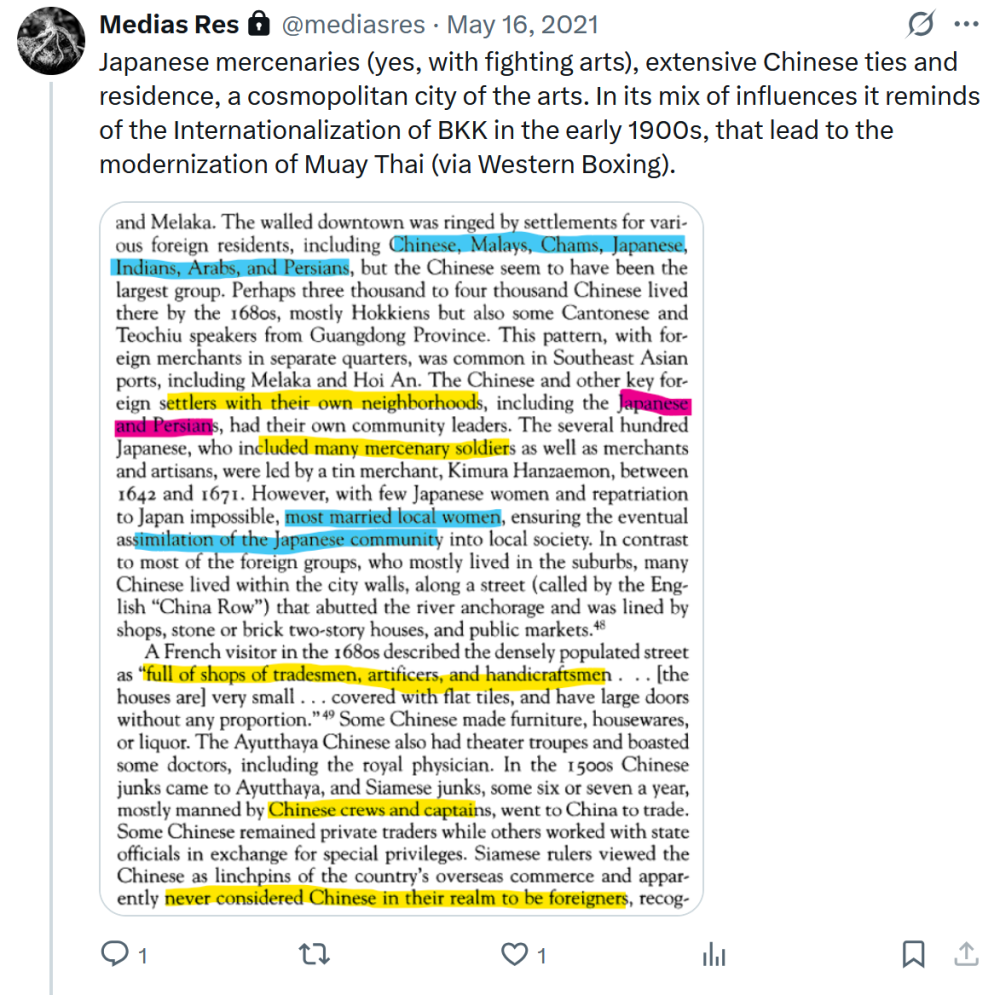

Incidentally, any such Ayutthaya ring-to-ring developments hold the historical potential for lots of cross-pollination from other fighting arts, as Ayutthaya maintained huge mercenary forces, not only from Malaysia and the cusp of islands, but even an entire Japanese quarter, not to mention a strong commercially minded Chinese presence. These may have been years of truly "mixing" fighting arts in the gambling rings of the city (it is unknown just how separatist each culture was in this melting pot, perhaps each kept to their own in ring fighting).

-

1

1

-

-

For anyone who follows my writings I do not argue for any sense of a "pure" Muay Thai, or even Siamese fighting art history. Quite different than such I take one of Siam and Thai strengths is just how integrative they have been over centuries of development (while, importantly, preserving its core identity). For instance Western Boxing has had a powerful influence upon the form and development of Muay Thai for well over 100 years, and helped make it perhaps the premiere ring fighting art in the world, but Western Boxing itself was a very deep, complexly developed art which mapped quite well upon traditional Muay Thai in many areas, allowing it to flourish. This is quite different than the de-skilling that is happening in the sport right now, where instead the sport is being turned towards a less-skilled development, for really commercial reasons.

The story of whether the influx of attention, branding, not to mention the very important monetary investment that Entertainment Muay Thai has brought will actually help "save" traditional Muay Thai is yet to be written. It very well might, as the sport was reaching some important demographic and cultural dead-ends, and it needed an infusion. But, let's not have it be lost, what itself is being lost, which is the actual very high level of skill Thailand had produced...and how it had developed it. Let's keep our eye on the de-skilling.

-

1

1

-

-

One of the more slippery aspects of this change is that in its more extreme versions Entertainment Muay Thai was a redesign to actually produce Western (and other non-Thai) winners. It involved de-skilling the Thai sport simply because Thais were just too good at the more complex things. Yes, it was meant to appeal to International eyes, both in the crowd (tourist shows) and on streams, but the satisfying international element was actually Western (often White) winners of fights, and ultimately championship belts. The de-skilling of the sport and art was about tipping the playing field hard (involving also weigh-in changes that would favor larger bodied international fighters). Thais had to learn - and still have to learn - how to fight like the less skilled Westerners (and others). In some sense its a crazy, upside-down presentation of foreign "superiority", yes driven by hyper Capitalism and digital entertainment, but also one which harkens back to Colonialism where the Western power teaches the "native" "how its really done", and is assumed to just be superior in Nature. The point of fact is that Thais have been arguably the best combat sport fighters in the world over the last 50 years, and it is not without irony that the form of their skill degradation is sometimes framed as a return to Siam/Thai warfare roots. It's not. Its a simplification of ring fighting for the purpose of international appeal.

-

1

1

-

-

This is the difficult thing, as Muay Thai shifts to a tourism economy. Things like defense and balance development (along with timing) are very hard to develop in fighters. It takes years, and in Thailand much of it comes out of the kaimuay tradition of fighters raised and fighting since boys. Fights traditionally were scored to favor these things and the training reflected their higher-level maturation. They became embedded in the culture, and the significance of Muay Thai in Thailand, part of its "Form of Life". Teaching them required a rich subculture (which today is highly eroded), and knowledge was passed down in a non-instructive way. As Muay Thai becomes turned towards "action" moments, and incorporates the lessor-skilled non-Thai, defensive and balance roots are increasingly not fed, and will starve. Non-Thais become trainers, not developed in the kaimuay tradition, favoring things they can teach well, especially memorized offensive combos (the new signature of Entertainment sport). The deeper enrichments of balance, control and defense pass away, and notably, as fighters are discouraged from displaying these things offense-first, trade-oriented attacks actually become MORE successful. It becomes a self-feeding system of entertainment.

-

1

1

-

-

Some common sense thoughts. Leaving aside the obvious fantasy that somehow what people are doing in a commercial ring is anything close to martial combat on a field featuring a huge diversity of weapons, multiple lines of attack and various stratagems, there are some things about this image that not only gets things wrong, it gets them 180 degrees wrong.

Balance First - One of the essential elements on traditional Muay Thai is the scoring of "balance", both physical balance, but also psychological balance. Are you in "control" of yourself. In a field conflict the last thing you would want is to fall off balance, or go to the ground. And you certainly don't want to be emotionally out of control. Balance is hard to develop, so moving onto other more easy to train skills (like combo-ing) becomes tempting, as Muay Thai becomes "modernized" for tourism. Throwing 100% power, off-balance combos over and over is not really "martial".

Defense - On a SEA pre-modern complex "battlefield", unless you are just being Berserk, defense matters first. You do not expose yourself to even significant wounding (because deadly infection rates would be high). Instead, a priority would be defense-first. One of the aspects of traditional Muay Thai is that it largely emphasizes this A fighter who can defend and control the fight through defensive prowess was rewarded, scoring was biased along this slant for a substantial part of its history.

These two core aspects of Thailand's traditional Muay Thai, scored balance and scored defense, are really closer to "martial" principles than anything you'd find in a highlight reel.

What hyper-aggressive, low-defense, high-risk Entertainment Muay Thai does is make us FEEL like its war, largely from how we've come to feel about combat in cinema, from Kung-Fu showdowns to WW1 trench charges. Its there for Entertainment, and often really just to produce highlight KOs that can go into social media streams and spread the brand, so people don't even really have to watch the fight. That's okay, part of sport is just "entertainment", and can be swapped with the John Wick 4, or even cute sqeeee kittens on the Gram. But, let's not fool ourselves that it is somehow journeying back into its warfare roots, in terms of how its actually fought. Non-star Thai fighters today are constantly urged to give up all semblance of defensive control, to "sped up" with the new combos they are training on, and take high level trading risks with often bigger foreign opponents who train the same. The core, deeper aspects of fight prowess, control over oneself and defensive priority, is being left behind and some really may be lost.

Let's not even talk about the much deeper disparities between ring Muay Thai and much of the warfare in the 1700s in Siam. The battle field had European rifle regiments, elephants, cavalries and every fighter was armed with a blade (on the larger scale most were probably farmers who used their harvest blades), and great deal of it was siege warfare. People were not just giving up their bodies in swinging attacks over and over. There is also significant historical evidence that European warfare was very different than SEA warfare, in that killing the enemy was much less a goal than capturing and enslaving them, because captured "enemy", often full villages, meant wealth (labor). I believe I read an estimate that Burma took more than 10,000 Siamese back to Burma as labor, some for even high level artisan labor, when Ayutthaya fell. Warfare was often a game of capture, and it was fought seasonally - there was "war season" just as wild elephants were seasonally captured.

-

1

1

-

-

I'm sorry I don't really know. Sylvie is in touch with a collector and this person is where she buys hers, but there are not multiple copies available. Maybe someone else would know of a larger source.

-

-

I think people are becoming aware that there is a kind of tourism pipeline that has developed, from commercial gyms to Entertainment Muay Thai, put on for tourists. Tourists working for tourists in tourism "shows", (notably a sport redesigned for tourists to win). There are a lot of things of value in these fights, but people are also becoming aware that they are on a conveyor belt that was made for them. The Muay Thai they came for is far from these experiences. It's very hard to work your way free from this "system" which has become pervasively pointed at the Westerner.

Gyms face the problem that people come to them and say: I don't want to fight on these shows, under these rules...because this is actually a tourism system. It's made for you. For you.

-

1

1

-

-

Somehow this is very beautiful (even if common). What a beautiful fight Crawford fought. I think there were some definite dangers in this fight, that people have been ungenerous with Canelo. That hook to the body was becoming a problem, and could even have won it, but Crawford solved it in a subtle and shifting ways.

-

Buntan vs Hemetsberger. Very cool to see Hemetsberger fight in such a disciplined, and really very Allycia way. And be so very well prepared.

-

There is a very strange thing happening. Waves of affluent tourism are being sent to what really is a Low Caste art and sport. Many do not realize that Thailand's society is still somewhat an operational, invisible caste system, itself formed from Siam's own, once widespread slavery and indentured servitude. The ironic thing is that some of Muay Thai's most beautiful, meaningful traditions of meaning - the things that lift it from just being a rationalized combat sport, or entertainment violence, and very likely also what made Thailand's nakmuay so incredibly effective as fighters - themselves are woven into and from that invisible caste system. It is quite extraordinary that this lower caste art and sport is becoming gentrified by both hi-so internationism and government tourism ambitions. That the sport itself is being altered so that the affluent can win, and so that traditions (and aspects of invisible caste) will be eroded. I'm not sure anything like this has ever happened before in history, I can't think of an immediate parallel.When (relatively) affluent adventure tourists attempt to partake directly in "traditional" Muay Thai they are crossing many invisible lines in the culture. A (relatively) high status person is trying to enter a low status position, blind to even the nature of "status".

-

1

1

-

-

What we are witnessing is really a kind of gentrification of Muay Thai.

-

https://www.instagram.com/reel/CuuXPkmp-SK/?igsh=MW1wcW1oZDZtMzgybg%3D%3D

A great little clip of legends Yodkhunpon and Samson clinching back in Roi Et where they were upcoming Isaan fighters. Notably, you see ZERO "pretzel" (the pretzel discussed here at some length: https://www.patreon.com/posts/130545342/ ); also Samson clearly the stronger clinch fighter technically, see how everything is wrists and hands and neck, whereas Yodkhunpon avoids any of those leverages, which Samson sews together somewhat relentlessly. Also, those two nice rips. Yodkhunpon a different sort of clincher, and Sylvie and I joke today that a reason why Yodkhunpon is so anti-clinch in their sparring is that he had to suffer through clinching with Samson on the comeup, a fighter here likely at least a weight class lower. Namkabuan used to talk about how having to train against his Muay Khao brother Namphon really shaped him.

-

1

1

-

-

-

There is a mode of perception that developing Thais have less of today. Ever notice how your Thai trainer can humorously imitated exactly what you are doing wrong in an exaggerated way? How they can cartoonize the body. This likely comes out of the mode of learning itself back in the day, the way that "ruup" (form) was a mode of education and emulation. Intelligent, affective projection and modeling, in play, was how the art was communicated. With today's attention spans, difference in motivations, and really radically different Gaze Economies in gyms, this channel of development is highly diminished. It's a lost skill of perception.

The rationalization of the sport, the mechanization and abstraction of the sport certainly doesn't help in this, because the sense of embodied "aura" has been lost. And Westerners enter the sport largely from this other direction, meeting the new gen of Thais in the middle, far from where the sport and art developed and was passed between persons.

-

1

1

-

-

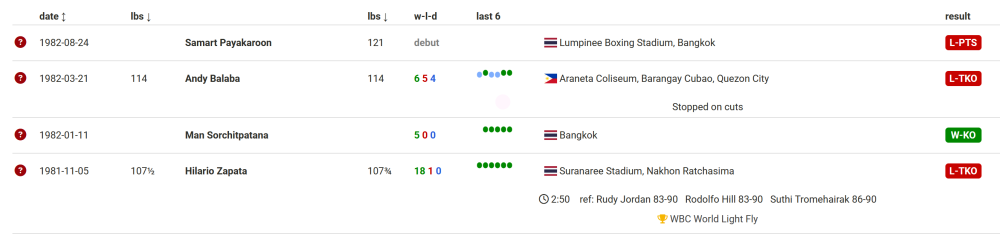

Wow, just had an amazing conversation with Karuhat, him telling us about a Saturday Boxing show put on by OneSongChai which featured lots of Thai Muay Thai stars, in which he fought twice, losing to Nungubon and to a Muangsurin fighter whose name escapes me. Most amazing is that he said that he had no special boxing training, in terms of kru, just mixing up boxing imitation training in his small Sor. Supawan gym, and Thai principles (he's not a bad boxer even today). He lost both fights, but he also said he WANTED to lose, because if you showed promise you would be drafted onto the Thai National team at the time (he even DID get drafted onto the team, it seems, fighting on am boxing fight on the King's Birthday vs a Cuban who was incredibly fast). Amateur boxing meant lots of hard training, but not a lot of fighting, and the pay was horrible. It was the last thing he wanted. He was a star in Muay Thai, had great kaduas, fought every month, honed his femeu style. Even pro boxing wasn't that lucrative because fighters only kept 30% of the purse (in Muay Thai it was 50%), and usually didn't fight that much. He said in one of his boxing fights he even stuck his head out of the ropes, he wanted so not to do this.

I asked him who was on the Thai National team the brief time he was there and he said Sittichai, Jongsanan and Coban came to mind.

I also asked why it was that fighters like him could just kind of develop boxing skills without specific boxing instruction, but Thai fighters today can have all kinds of boxing instruction, even from legends, and not develop the same level of boxing skills. He said "electronics"...all the distractions. The phones, etc. He said that you used to really pay attention, go to fights and emulate fighters, really absorb their powers and ways, imitate them in the gym, steal from everywhere, now Thai fighters are just doing what they are told and going to their phones. There is no attentiveness.

I asked about Namkabuan (who is in one of these SongChai boxing fights below vs Chatchai), and his "nongki bounce" footwork which seemed unusual for Muay Thai, if that came from boxing. And he said that this is just normal Muay Thai to him. You can see some of that in this clip (really, look to the Muay Thai Library session to see so much more).

When asked about where Namkabuan got his boxing (in the video below) he said Nongkipahayuth probably (Karuhat spent time up there because he was friends with Namphon). Maybe some from Muangsurin (a big boxing gym the brothers sometimes trained at), but he really didn't think knowing boxing as Namkabuan did was the result of special training.

-

1

1

-

-

Was talking to Sylvie about this very interesting historical cycle involving gambling in Siam and then Thailand. To be very cartoonish about it, provincial farmers would sell their crop and put the money in the ground, literally burying it. This would take the money out of the economy. Gambling worked as a counter to this trend, recirculating currency...but, when they would come to the capital to sell their crops in the 1900s this worked too much to the extreme. Chinese mafia and dens of gambling would drain them of their payouts, leaving them and their families enslaved (servitude). So, capital Chinese mafia gambling, which was very pronounced (gambling at one point in the early 20th century accounting for more than a quarter of the government's income through tax farms) developed a strong moral taint, farmers would loose their livelihood and fall into servitude in dramatic, destructive trends. King Vajirivudh ended up outlawing gambling in the 1920s. But, there is a kind of moral-economic tension or spectrum, between the money that stays in the ground (a traditional picture), and money that circulates in the wider, urban economy, with corrosive effects. And even to this day you have this pattern in Muay Thai, with Chinese ancestry Bangkok promoters who have been aligned with mafia and gambling (scene as a moral vice still), and the provincial fighter, who comes to the capital, looking to win big. There is a tension between tradition and custom in the land, and the (International) urban Casino. What is interesting though, the custom of local market gambling also is that which shaped provincial Muay Thai itself, which I detail here:

On the history and psychology of gambling, I wrote about this here (there you can find the pdf of Gambling, the State and Society in Siam, c. 1880-1945 by James Alastair Warren which is very, very good):

-

1

1

-

-

to hold perception (from which we get aesthetics), meaning "to be quick to sense" (Aristotle, Arist.EN1098a2). Aesthetics in this sense is developing the hair-triggers of perceptive experience, to attune. Animals are very quick to perceive, attuned by evolutionary pressures, through aesthetics humans attain something of the animal, in the intensity and the speed.

When one changes the aesthetics of the sport, its rule set, its judgements, one is changing the speeds of perception, and to what one is attuned. But, culturally, deeper aesthetics develop over time, are embedded in layers, in sediments of perception, in habitus, so external imposition of aesthetics, for instance Westernized or Internationalized fighting aesthetics, messes with perceptual DNA, and with the very experiences of watching.

In this way the learning of Thailand's traditional Muay Thai is not learning "techniques", or even principles of action. It's learning to sense, to perceive. It is for this reason that proprioceptive things like "balance" and ease (ning) as well as external signatures of each, as well as "ruup" (form) are hidden decisive elements in traditional scoring (and important aspects of training, well beyond things like technical precision).

-

https://www.instagram.com/p/DNJE3xmsiks/

This is how far Entertainment has pervaded. Tapaokaew vs Nuenglanlek. Nuenglanlek losing the fight in the clinch asks Tapaokaew to go toe to toe for the end of the 5th round so fighters can get the bonus. This is basically...let's stop fighting a "real" fight, you know, one fighter out-skilling another, and instead let's "put on a show" for the Entertainment bonus. That RWS itself posts this, selling the action, just is a deeper dive into building a "content" generator sport. This is just the shaping of the sport by commerce and moving to online content and in-person tourism, away from in-person passionate, knowledgeable fandom...which I suspect isn't sustainable as a business model, and certainly won't develop the highest level skills (building the sport long term). It's also an interesting reversal of the supposedly "fake" dance offs in the 5th round, now there is a "show" of action. This likely will become a trend as fighters learn new ways to play the 5th round out. RWS has a tough line to ride, as the nexus space, the limnal space between pure Aggro ONE marketing and gambled traditional stadium Muay Thai. These are nuances and changes in that space.

-

1

1

-

-

timestamped, Kristen Stewart says an interesting here on what would happen if the entire Hollywood machine of movies came crashing down, small film culture would still persist in pockets, people making small films. In a flash I repositioned on what would happen if Bangkok Muay Thai just broke down and was no more. This isn't to say that there isn't important advocacy, or that globalizing, commodifying, tourism-izing trends can't destroy something...but it is to say that there is resilience.

-

1

1

-

-

Two experiments in images from the other day. Exploring lines of force inside movement and position.

-

1

1

-

-

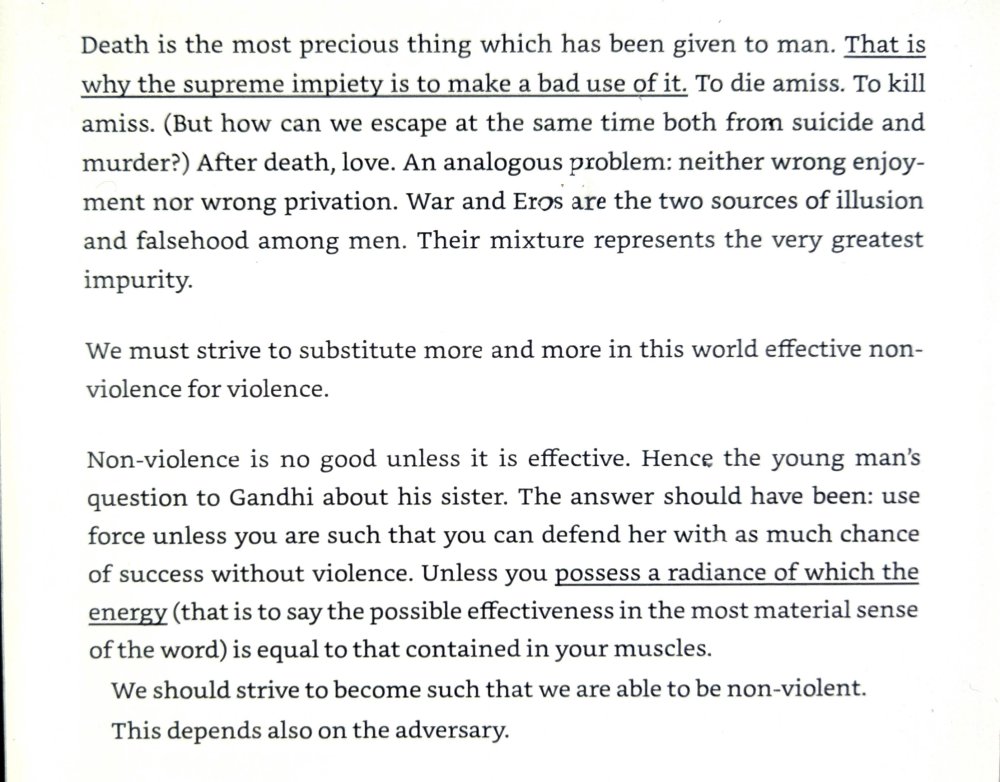

Nak Muay as pathogenisis creation, the path of suffering (Greek, pathos, to undergo), in the name of surpassing violence with violence as your possible tool. Weil says of the tree of Life, it is only vertical. It has no fruit.

-

On 8/10/2025 at 7:58 AM, Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu said:

Non-Violence, Radiance and Muay Thai

Simone Weil uncovers the rite-like secret to the beauty of Muay Thai's emphasis on control...the production of Radient Energy. This can only come from the potentials of violence. This is why its a martial sport and features the escalation of skill and spirit. A martial sport.

What is compelling is that one cannot develope non-violent (less violent) skills without facing violence or without losing to violence in parts and inches.

Following on this thought, Simone invokes such a poetic picture of wearing oneself through Time and Space (here, the ring, the kaimuay) which parallels the Nak Muay. There is something here.

-

There is an entirely separate dimension of gaze economy in mixed-culture gyms that I'd love to write about, but bookmarking here so to maybe pick it up another day, and that is the way in which visiting Westerners enter training spaces and do not even look so much at Thais in the space, for orientation (despite all that I wrote so far above on this), and really look horizontally at other, longer term farang in spaces. Writing even from our first experiences in Thailand, in mixed-culture gym spaces, visiting Thailand even in the most touristed areas can be a very intense experience of foreign-ness, and entering a Muay Thai gym, even the most commercial of these spaces (which are themselves quite scocially agonistic and competitive) can be an emotional experience without compass. One enters these spaces looking for "how to do it", and immediately one takes social cues from all the other Western traveling fighters. The at-first imitative, and oriented gaze is towards longer term Westerners who "know the ropes", eventually will become emulative, because part of training in Thailand is learning how to be a traveling fighter, involving many things other than simply the training. Everything from where and when to drink water, to where eat, to how to comport oneself, the sum total of "how to go about things" largely learned through imitating longer term traveling fighters. We remember - and this is just a small thing - that Sylvie at Lanna so many years ago (Lanna being one of the more established "authentic" mix-culture gyms in Thailand, with a lengthy history), had to mentally separate herself out from the 40 minute hand-wrapping beginning of training that had grown among Western traveling fighters, to begin every morning's training, where you not only wrap hands, quite slowly, coming back from your run (for those that ran, most did a pretty substantial run), but really just talking, shooting the breeze, or just being a part of that mini-habitus of training preparation, sitting on the bench with others, even if you kept by yourself. This was a sub-culture of "how to begin training" that had developed around longer term fighters, really a small thing, but it was its own reality, its own pace, an important part of the traveling culture of the gym at the time, quite apart from the Thai-led training. It was emulative.

Our time at Lanna then, but also at several other gyms, made us quite aware of how gyms actually were in laminate layers of habitus, a Thai and non-Thai side, and that long term fighters, or adventure tourists played a very large part in creating and bearing the Western sub-culture, in part because it was constantly fed by new, fairly disoriented participants.

******

We are left with a mirroring hypermasculinity, between two cultures / sub-cultures. The Westerner engages in a Hard Body hypermasculinity, and probably a (pomo) Colonialist adventurist hypermasculinity, and the Thai Nak Muay is participating in a hypermasculinity which somewhat resides in his (her) past, that out of which the art and sport of Muay Thai has grown (Peter Vail cited above). The Nak Muay is encountering the project of developing and expressing the (somewhat classic, somewhat nostalgic) hypermasculinity of his (her) own culture, but also caught in the globalized commerce, the subjectivity of Internationalization, which brings these two cultures / sub-cultures together. The newly arrived traveling fighter from the West is thrown in between these two performances in really what can be a heady, transformative way, emulating well-grounded Westerners, weaving himself (herself) into that fabric, fashioning that hypermasculine identity and performance, that gaze economy, while that masculinity itself has been in the longer term developed in emulative fashion on the Thai Body, at least in terms of the transformation being attempted, to lean into Thai, classic hypermasculinity. In this several things map between the two hypermasculinities, but really many more do not. All this while, Thai Nak Muay in these spaces are also being swept up toward a new, globalized masculine, following the new gaze economies the body is exposed to, including those digital economies of gaze.

-

1

1

-

Journaling - Readings, Muay Thai, Concepts and Articulations

in Kevin's Corner - Muay Thai, Philosophy & Ethics

Posted

Baudrillard. This is the art of Muay Thai.