-

Posts

2,273 -

Joined

-

Days Won

502

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

Defense Even the best intentioned don't train actual Muay Thai, the Muay Thai of Thailand. The foreigner, even quite knowing ones, train 90%-95% offense, when in fact Muay Thai is probably about 70% defense. There is a reason why in Thailand when you have the lead you defend the lead. This is the position of the superior. Every fighter who gains the lead learns how to defend it. This is what distinguishes it - in skill, in spirit. The foreigner only SEES offense. Trains its words and vocabulary, missing the entire thing. Even the high-so Thai, quite-Americanized, sought to take out as much defense as possible, every drop and drip of it, because even Thais can be very far from the root and tree of their sport, separated by class and commerce.

-

The Muay Thai Library is so incredible. Today I was realizing how many men we have filmed with who have passed. This is a generational greatness, and it is an honor to have met these men, and in some cases to have come to have known them. Taking a moment to think of them and feel them. Each of these men a universe of a muay within them, of which we have touched just a teaspoon. Andy Thompson Morakot Sor. Tammarangsi Sangtiennoi Sor Rungroj Namkabuan Nongkipahuyut Sirimonkol Looksiripat Kaisuwit Sungila Nongki

-

We've been watching a lot of David Lynch since he passed. Rewatches of Lost Highways, Wild At Heart, Blue Velvet, Inland Empire...and now working through Twin Peaks. I talk about it a lot. One of the things coming through is the way that he works with melodrama, and in Twin Peaks the soap opera tv form of it. It allows archetypal (in fact at times wooden) characters who are moving through scripts they repeat, stories that are told about these kinds of characters. As the actors say in Inland Empire (paraphrased), "I thought we were doing an original script, I wouldn't agree to do a remake". IN this sense Lynch is saying we are all doing "remakes" as we repeat the scripts we have inherited. But the characters are experiencing very real, intense emotions in these scenes, just like we do in our "real" lives. We are acting in scripts, doing "remakes", but living with tremendous pathos within them. Lynch, I imagine, is making two points about our pathos. There are two doors. The first is akin to Buddhistic (un)attachment. The only reason we are suffering (or enjoying) intensely is because we are attached to these wooden characters, the "remake" we are making. If we saw that these are just recycled characters the grip of our emotions would lessen. But, there is within his films & show another door. Sometimes characters suffer or intensify their experiences so thoroughly they transcend it, they are transformed, in a passion-of-Christ (archetype) type intensification, often it is female characters who pass through this door, with a sort of glowing, mixed divinity. As such with the Muay Thai fighter who is a woman, in a certain way. Female fighters especially are putting on the "clothes" of the fighter, because the fighter is a model of hypermasculinity in many cultural traditions.

-

Found the old footage of Sylvie's 2nd fight (Fight 12) vs Angela Hill, accidentally, waking up my very old YouTube account the other day. We thought the video of both those fights were lost, taken down by their team to keep opponents from scouting her, as it was, back in the amateur NY days. Sylvie tells the story on her blog, taking the fight vs the best female fighter on the East coast on 24 hrs notice (wrecked on fertility hormones because she was donating her eggs very soon to afford to come back to Thailand. Not training, giving up big weight, out of shape driving straight from work to the fight), it was quite a thing. Perhaps her most "raw" fight, never to win such a fight in a 100 years. Angela all crisp in her technique, she was a bit of a situational weight-bully back in the day as that was the ethic you took every advantage you could get, and she was properly feared as big, aggressive, skilled fighter, sometimes finding herself fighting the proper 100-102 lb girls who didn't even have a weight class at 105 lb; not a criticism, nothing unfairly done as there were so few girls, but few wanted to face her in that small scene where fighters really valued victories. She had big dreams as a fighter and later ended up having to fight up a ton in the big girls of the UFC, something that probably deprived her of the dominance that would have made her a big star, giving up all that weight in the ring. If she had been fighting down in the UFC it would have likely played out quite differently. In fighting if you fight enough it goes and comes around, you go through every permutation. Cool stuff. But, Sylvie didn't get knocked out, which was a big aim, and got to just be raw in there one more time. That's what it was about that time, that's what coming to Thailand was about then, just to find opportunities to fight...at all. Sylvie took every fight possible because you might not fight again. Each fight chance felt like it might be the last, and you just could not grow without fighting, a principle she would embody in the many years to come. In some ways its my favorite fight of Sylvie's, its not even close...but close to the beating heart of it all. After the fight Angela was on the mic before the crowd, this was about when she herself was running out of opportunities in Muay Thai, and she announced to the crowd something like "I bet Sylvie will fight again", like...this isn't Sylvie's last fight, even though I whopped her...two-hundred-and-74 fights ago. That was the beating heart then. I love this fight. You see the raw, the "what was about to happen" that's beneath all those hundreds of fights to come...if you have eyes for it, and all the documentation of the sport and its art, all the expertise she would seek and learn, because she had none of it then. In some ways, its proper for this fight to be private (and we'll keep it so). Because its the hidden crucible, just before we came to Thailand. Sylvie almost died on the donation table (at least I thought she was going to die as doctors came rushing in), so at least her heart probably stopped, they never told us. And we were landing in a plane in Thailand to actually LEARN Muay Thai properly and fight it properly 2 months later. She was in the ring a month after that. 2012. Fight 13.

-

People think its the padman's job (in Thailand) to make you tired. No...its your job to make your padman tired, especially if you are a dern fighter. But this does NOT mean go harder. It may mean that, but it does not principally that. Understand, you are learning when you do padwork, and if what you are learning is "This guy makes me tired", that is one of the last things you want to learn. Instead, use padwork to find the inner-patterns of rest, both physically and psychologically, the quiet ways experienced padmen work to recover, breathe, pace, control the tempo. And learn to take these, quietly, away. If you can do it to your experienced padman, you can do it to your opponent.

-

Watching yet another very skilled Japanese Muay Thai fighter on Phetyindee the other day, I remain convinced - very broadly - that though Japanese fighters definitely hold the Thais, in fact Thailand's Muay Thai, in allure, they principally train in the aesthetic of Anime. This is to say, they are guided by a visual aesthetic that almost entirely forgets the art of Time, which is where almost all the art of Muay Thai is. They honestly, at some very deep level, "doing" Anime, which isn't Muay Thai at all.

-

Caring for Arjan Gimyu Sylvie did a very good deed today. Arjan Gimyu in his 80s, 2x Coach of the Year, kru of Kaensak and so many other champions, has been somewhat confined to his room because of the air quality and his asthma. He lives a very spar life on a government check, just really a room and a radio and a fan. He usually drives over to Rambaa's gym in the afternoons so he can be in a kaimuay, the real form of the sport where kids are developing, pads and bags popping everywhere, but he's had to stay home lately. Sylvie bought a good Hepa airfilter he can run at night to clean the rooms air, dropping it off, plugging it in and showing him how to use it. She texts with him regularly when he can't make it to the gym, talking about how fighters did and such, keeping in contact. Just knowing that someone cares just a little bit more than expected goes a very long way.

-

Starting this journal because I really am becoming part of a resistance to Social Media, which is a form of pulverization. I just have to have somewhere to put my aesthetic impressions or thoughts. I'm not sure how much this will continue, but starting it helps. Saw two spectacular movies I really didn't know. The Big Risk (1960) with Lino Ventura and Fassbinder's Love Is Colder Than Death (1969). Wow, both visually arresting. The Big Risk full of vistas, framed out interiors, face portraiture, a beautiful serial on-the-run story that filled me with visual imagination. Love is Colder Than Death has incredible blownout compositions with dark figures (scenes on white walls exposed to the black leather jackets, etc). Both have those Living Greys where grey becomes an unbelieveable White in the Mind's Eye.

-

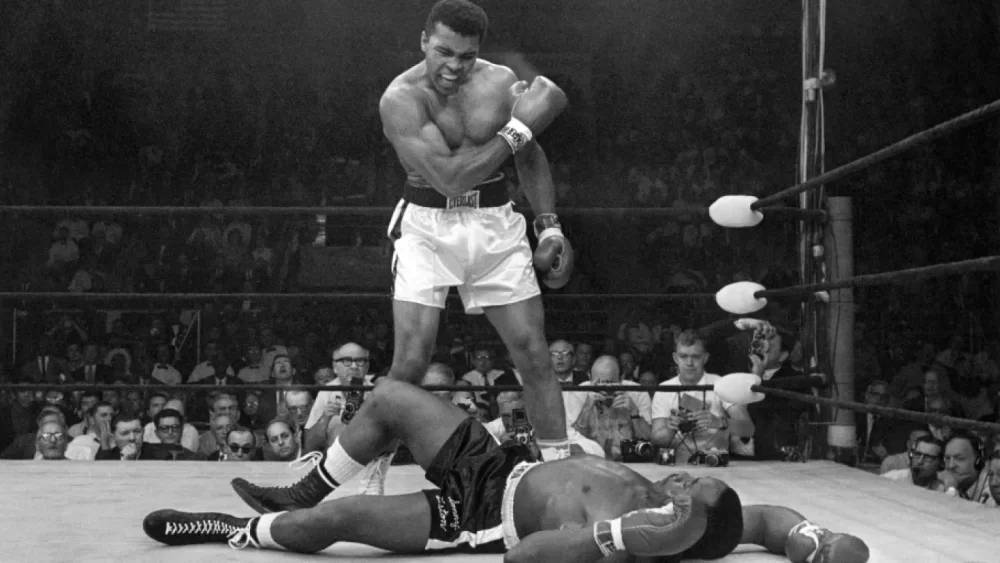

You get some of this in the somewhat wide shot of Ali's famous "What's My Name?" photo vs Ernie Terrell (1967). You need the rest of the "world" to feel the meaning of this moment. You need the composition including the white faces of photographers, you need the darkness of the crowd. The eye does go immediately to his asserting face, but it also swims around, settling on the prone opponent. It's hard to get these kinds of shots (and this one is once in a 100 years). But cameras in the day forced a development of compositional focus. Thinking and seeing in wide requires using wide.

-

This photo accomplishes something, a focus, that is quite hard to achieve outside of ultrawide. You need the rest of the world, the gym world as a space to indicate how this very small thing is the focus. It's the contrast. You can miss the pointing finger, and that's the point. The feet are so much of the key to effective movement, which is key to effective striking & fighting. You don't want the finger to be the "point" of the photo, but rather its after-point, which communicates a wide (sic) range of relationships the information and the gesture. Not only the case in teaching, in Muay if the eye is very close and selective, one can frame very important details of a moment in a great complex of composition.

-

What's nice is that the lens distortion which sometimes might be seen as a drawback can actually bring forth the actual form of strikes and movements, extending lines and speaking the truth about the moment in a way that a visually "accurate" lens would not, as in this shot where the wide stance, and the rotation coming out up from the floor has a kind of lyrical quality. You can see the communication through lines of force.

-

I shot close to the floor as is often suggested on ultrawide, and I've had very dramatic shots from below with the lens in the past, but honestly I prefer the straight on tableau effect. Though, one of the benefits of being low is that architectural elements can really pop an give that Escher like effect (like here). I do like these photos, a lot, but I'm drawn to the wide lens I think much more in terms of that tableau 1960s cinema effect.

-

Just some notes from today's casual shoot. I don't always photograph at Chatchai's (we go 2x a month), but it is a great opportunity to just experiment with aesthetics, or to change the way I see. Ultrawide & Wide for Muay Thai Photography I've always been very drawn to wide lenses for Muay Thai photography, if only to get away from all the focus on "the action" and the proverbial sweat-spray shot. Mostly I've shot with longer lenses to get away from this moving in the opposite direction, to explore more the psychological aspects of fighting, and to locate what might be called sculptural body forms, but honestly, I've wanted much more to shoot in wider lenses, because I think the sense of space, of emptiness, is really what the art of fighting is about, like scuba diving is about what you do IN the ocean. Its harder to do in fights themselves because you don't have control over your setting and are locked more or less into one or only a few vantage points. I've been lately interested in the Contax 645 35mm lens (27mm full frame), (above), adapted for the GFX system, in part because it seems to give that "what the eye sees" kind of field of view, something that I find in many of the beautiful films of the 1960s, and some early documentary photography. You can see a short article on the lens that attracted me. I want a little more of that tableau feeling, with some beautiful sample shots. I love this sort of photography, and I'd like to bring that nobility to Muay Thai. What I'm interested in with this Contax lens is that many times I encounter situational muay, often with older fighters, scenes that are full of details and composition, that it just feels like it has to all be captured, rendered, brought forward. With that in mind I went back to my Fujifilm 8-16mm (12-24mm ff), above, which I really forget how much I love, a wide angle zoom on the X-series cameras that is underrated in the images it can pull. I have shot some very memorable photos with it. Today I shot Sylvie training with Chatchai at his Thai Payak gym in Bangkok just to get reacquainted with the wider view. I want to get used to seeing-in-wide again. You can maybe see what I see even in these somewhat casual shots, the way that the space envelopes the figures, and the figures almost arise from it. Note. I'm not a super technical photographer, and not really a gear person. I see things I like in my mind, my hands, and then look for ways to achieve it. I do like the 8-16mm, and its zoom is really very helpful in muay settings where you cannot change your position easily to alter the composition. With ultrawide this is really important especially regarding the distortion, not only how much distortion there is, but what it is that is distorted. The zoom is super valuable. photos on this thread are unfortunately compressed and lose sharpness. I'm hoping to see more wide angle and even ultra wide treatment of the sport, because the art is really all about the spaces that hold it. And I've ordered the Contax lens and the adapter, the first time I'll have shot with a vintage lens. I'm very excited to see what will show up on the very large and detailed GFX files.

-

Sometimes I muse that Muay Thai, Thailand's Muay Thai is like the elephant. One time integrated within the society, at the village shore at the forest for instance in Surin (a folding of the human & the elephant culture), and then become the tank of the military empire, then the diesel truck of the lumber and other industry, now almost entirely existing within the country for the tourist, a bend of fate I do not want for Muay Thai...but today, visiting this one who lives near our house, I feel the depression, the majestic depression of her. Today I feel her. A short film study I made.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.