Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 05/13/2024 in all areas

-

In November I'll be going to Thailand for 4 weeks mostly to train and hopefully fight. Last time I went to Phuket following @Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu's incredibly helpful advice, and muay thai-wise it was everything I wanted. However, I'm looking for a bit more of a pleasant place this time, maybe a bit less noisy and crowded. I'm considering Koh Samui, but I'm not sure if it fits that description, nor do I know anything about the muay thai scene there. Has anyone here fought in Koh Samui, or knows anything about the fight opportunities there? Any gym recommendations? Right now I'm fighting mostly pro-am (semi-pro?) in the UK, so I'm not exactly a beginner, but not a pro either. I walk around at 65-70kg and have a defensive, kick-heavy style. When I went to Phuket Fight Club I had no issues finding suitable sparring and clinching partners, but I'm wondering whether there are any gyms in Koh Samui that would provide that as well. I'm also open to other location suggestions1 point

-

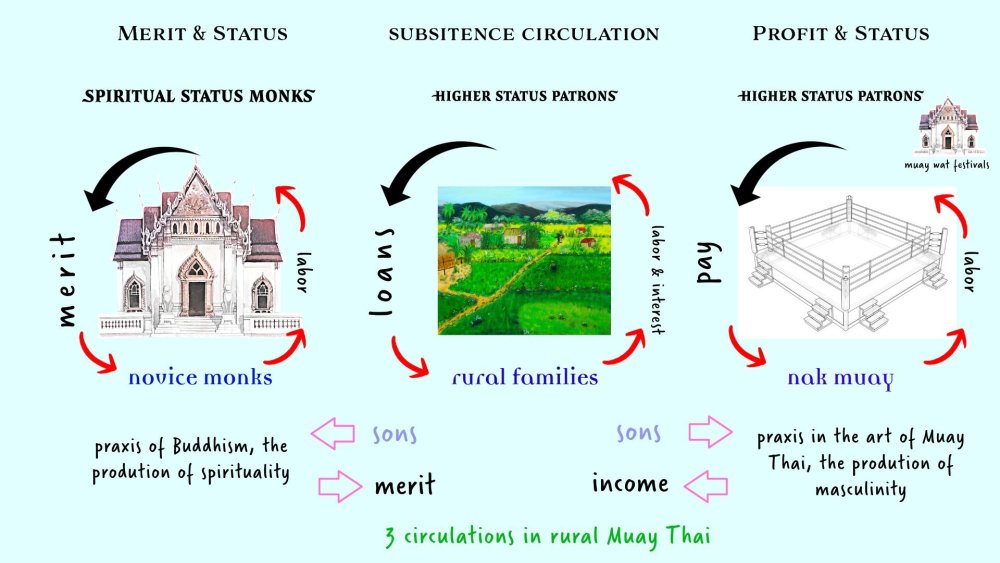

The above is a rough sketch of the triune circulations that engendered Thailand's rural Muay Thai, under the description of Peter Vail's dissertation "Violence & Control: Social and Cultural Dimensions in Thai Boxing" (1998). His dissertation captures Muay Thai just after its peak in the Golden Age (1980-1994), and focuses on the region around Khorat. what follows is just going to be some broadbrush patterning drawn from the work, and my other readings on Siamese/Thai history and that of Southeast Asia. One of the things that Peter Vail is really good at is bringing together Thailand's Muay Thai and Buddhism, especially in the production of (ideal) masculinity. In this post you can read about that nexus: Thai Masculinity: Positioning Nak Muay Between Monkhood and Nak Leng. The sketch above brings out the larger, more materialist aspects of the relationship between Buddhism and Muay Thai, the way in which Thai wats (temples) operate within the production of merit (positive spiritual karma), in parallel to how Thai kaimuay (camps) and festival fights (often on temple grounds) operate to produce earned income, through a gambling (chance-status) marketplace of fighting. These two economies flow both merit and income into the (here very simplified) subsistence economy of rice farming. Thai farming labor does not really make money, nor particularly symbolic merit, and its sons become novice monks or nak muay, just to name two options, each of which circulate in the community. Merit, social status & income flow from these into the family. And following Vail, the kaimuay-festival-fight machine produces a culturally ideal masculinity, just as the wat-machine produces spiritual capital (as well as its own idealized masculinity). Each of them supplement to the middle circulation. You can see more economic details and some graphs of the relationship between local fighting and rural subsistence, in this post: There is another really interesting aspect that comes to the fore when you drawn back and see these three circulations side by side. Historically Siamese kingdoms drew their power largely through seasonal slave raiding warfare. Whole rural, outlying communities were captured and relocated to nearby lands where they could work as farmers and also serve in the military. There was a double sided dimension to their capture and labor that then persists, transformed, in these 3 circulations. It is as if the rural economies of Muay Thai in the 20th century expressed the much older divisions of slave and then indentured service of Siam's past. Rural farmers no longer worked for the kingdom, but rather worked to pay back loans (in patronage relationships which operated like a safety net against unsure crops), and sons (as nak muay) not only served in the national military, but also produced a warrior hypermasculinity in the art form and local fighting custom of Muay Thai. What was slavery (or a strongly indentured/corvee hierarchy) developed into a community of rural farming (with little hope for social advancement) and the art of Muay Thai festival fighting, which provided income in supplement to the farming way of life. When Slavery was abolished in Siam, by the Slavery Act R.S. 124 (1905), the Military Conscription Act came along with it, binding the newly freed young men to military service. In 1902, three years prior, religious reforms were passed against non-Thammayut Buddhism mahanikai practices – (often including magical practices). Siam sought to standardize Buddhism, but it was also working to shift political power away from regional wats and religious leaders. The Siamese wat likely carried its own largely unwritten history of Muay Thai heritage, a keeper and trainer of the technical art of Muay Thai (Boran), along side the arts of magical combat. (The history of the famed early 20th century policeman Khun Phantharakratchadet and his training at Wat Khao Aor is a very good case study). This was a potentiated martial force. Undermining the martial powers inherent in wat training, placing young men nationally under military conscription, and secularizing Muay Thai (including the formalization of Muay Boran schools and training, and its teaching in civic schools), moved trained man-power away from regional wats and the community. You can read a great account of this struggle between a central government and local religious power in "Of Buddhism and Militarism in Northern Thailand: Solving the Puzzle of the Saint Khruubaa Srivichai" (2014). For some time, after the Military Conscription Act, the main method of its legal avoidance was to become a monk. Siamese regional Buddhism and National military conscription stood at tension, as political and perhaps even to some degree martial man-powers. Several reforms worked to keep men from evading conscription via less-than-committed monkhood (for instance the institution the testing of the literacy of monks). This is only to say that the long history of Siamese Buddhism in the community, organized around the wat and the labor of village sons as novice monks, including the pedagogy of Muay Thai (Boran) lay in tension with the formation of a centralized, newly modernize Nation. When we see the circulation of sons' labor and merit in the wat, and the parallel festival fighting often under the auspices of the local wat, this is a deep rooted, historical connection. Muay Thai and the wat go together, and have gone together for perhaps much more than a century. These 3 circulations put the two in context with the 3rd of rural farming. above, the sacred cave of Wat Khao Aor near Phattalung in the South, where acolytes could undergo rites to make themselves magically invulnerable, my photograph The last provisional note I'd like to make is that in these 3 circulations you find a very ancient production. O. W. Wolters, a preeminent historian of Southeast Asia takes pains to draw a picture of mainland kingdom leadership which saw the ideal masculine chief as possessing what he calls "soul stuff". This soul stuff is an animistic vital relationship to power that expresses itself spiritually and martially. A King or chief is chief not because of bloodline, he argues, but because of his spiritual and martial prowess, the union of these two dimensions of power. It is a mistake in perception to take Thailand's Muay Thai practices in isolation. In that it makes sense as a meaningful production, a production of various surpluses (not just monetary, but also cultural surpluses), both strands, Buddhism and Muay Thai, need to be seen in the braid, I would argue. As ancient chiefs were once regarded as martially and spiritually formidable, rural Muay Thai circulations have also been braided in the wider sociological sense, in the production of merit and masculinity. You can see Wolters' notes on Soul Stuff and Martial/Spiritual prowess here:1 point

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.