Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 05/07/2024 in all areas

-

Thanks for providing this. I am beginner as well been only training for about a few months and am looking to suscribe to the pattern to access some of these sessions. Just curious are there specific exercises or bag work drills or other things that the videos clearly lay out that we can practice or is it more the knowledge of the techniques and then we have to figure out how to put the techniques into practice? I also wanted to say thank you and Sylvie so much for putting this together. The videos I have watched of you guys on YouTube really put into perspective the real essence of the Muay Thai culture that I feel is sometimes lacking in the gym I train in here in North America. My gym I train at is good for training but I do not get the same kind of education about the philosophy, spirituality and ethics I get in some of your podcast videos so thank you. Are there any specifics videos on the library that you suggest that has learnings on the philosophy or spiritual side of Muay Thai from any of the legends or Krus. Thank you too much again, your work is great appreciated!2 points

-

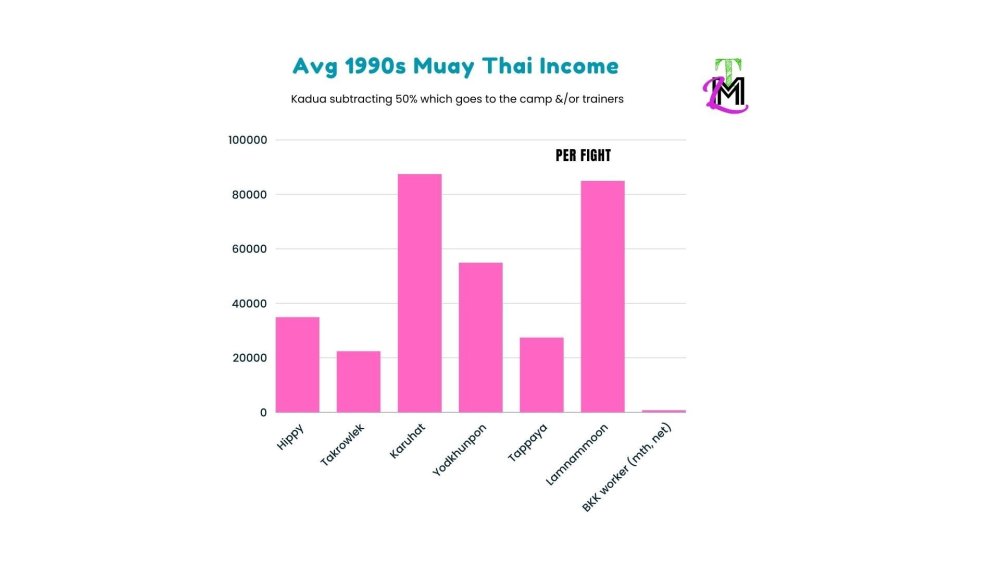

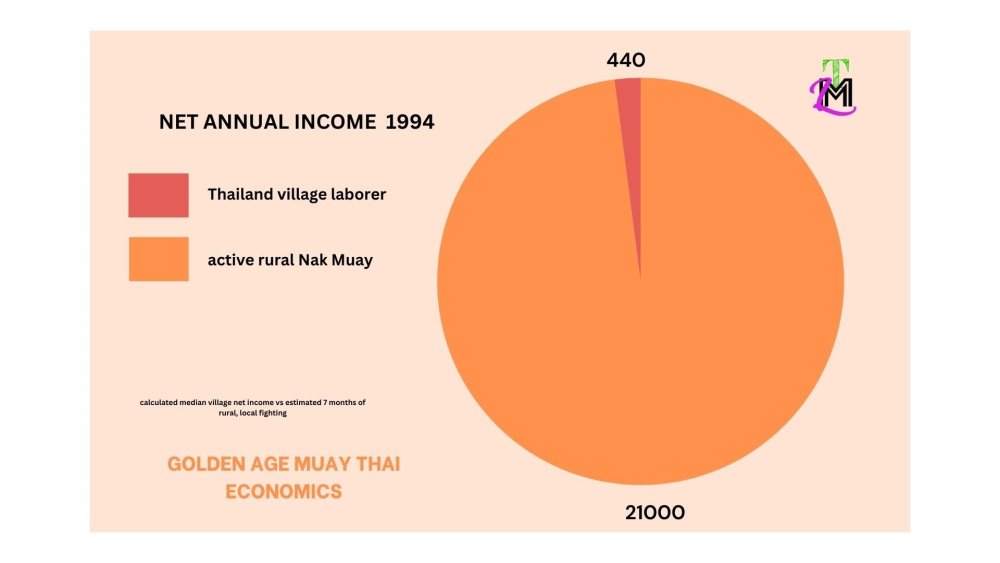

We tend to misunderstand Thailand when we think of individuals as discrete economic units. In a culture which is so heavily imbued with concepts of social debt, allegiance, patronage and hierarchy, the pure "individual" will always be a distortion, especially when thinking in terms of motivation. This being said, this piece is thinking about the economic motivations which shaped the prolific rural-regional fighting in Thailand's Golden Age of Muay Thai (1980-1995), mostly drawing on data and descriptions from Peter Vail's 1998 dissertation on Thailand's Muay Thai: Violence and Control: Social and Cultural Dimensions in Boxing, which I'm reading through for a second time now, the first being many years ago when we first moved to Thailand. One of the things I'm moving away from is the noted way in which Thailand's Muay Thai is characterized principally by its fights in the Bangkok National Stadia, which until recently held the international facing standard for its excellence as an art and sport. Muay Thai has been defined largely by its Rajadmnern and Lumpinee stadium example. Drawing back, it is meaningful perhaps to look beneath these high-profile fights and into the fabric which makes Thailand's Muay Thai like no other fighting art in the world: an historically persistent, vast rural-regional fighting practice and celebration, something which the economics of local fighting in Thailand in the 1990s sheds light on. In the larger frame, Muay Thai has been profoundly and prolifically fought throughout the provinces in Thailand (and Siam before that), intimately woven into its festival traditions for not only decades, but perhaps centuries. It has likely been part of its lasting agrarian culture, turning with the plantings and harvests, closely connected to the wat (Buddhist temple) and community, potential for millennia. It has an unwritten rural and regional heritage. And it has been this heritage and its widespread practice that has fed the stadia scene in the Capital for the last 100 years. Peter Vail is careful to point out that this robust fighting culture is not so much the case of a "hoop dreams" aim of long-shot stardom and life changing income, but rather one of a much closer, local practice. By the mid-1990s, with the Golden Age of Thailand's Muay Thai arguably coming to its close in the National stadia, rural, festival and regional Muay Thai was a very significant income source for the subsistence rural farming family, even for a modest, local fighter. The data Vail presents is from a 1994 survey, whose detailed accuracy may be question, but which also helps bring into broad picture the relative per capital wealth by region, and by urban and village groupings. "Savings" is qualified by the subtraction of expenses from income. Urban, more wage-oriented living was by far the more financially viable, with the best prospects in Bangkok. But even an average, non-exceptional fighter in local, festival fighting would in a single month - based on Vail's personal investigation, I believe primarily in Khorat - a very significant portion (a competitive sum) of even the annual savings that were possible of a Bangkok worker. (This graphic is based on Vail's somewhat conservative estimate that a local fighter could earn 3,000 baht fighting 3x a month in kadua fight pay alone - 1,000 baht a fight "take home" after a 50% cut taken by the gym). Because a fighter lives at the gym and has all his living expenses taken care of by the gym, potentially all of this income could clear expenses. This is leaving aside any income from fight gambling, tipouts from gamblers, or fighting in higher level local fights which would pay more. It's just an active, average rural-regional fighter in the mid-1990s. This would far outpace any of the annual totals of village labor averages in any of the four regions. In order to appreciate the economics of rural farming - and I certainly am no expert in this, only relating to the material - it seems important to understand that this is a subsistence way of life that somewhat systematically traded the possibility of increased income for the stability of loaned insurance against crop failures. Farming can be unpredictable, especially in the Northeast of Thailand which depends heavily on weather patterns as it does not irrigate from large rivers or lakes. Exchanging possible future gain for season-by-season stability builds in subsistence ways of life, and with them social stratification. This pattern goes quite far back in Siam to indentured labor, and farming practices that have been compared, perhaps with mixed accuracy, to Medieval fiefdoms, but in modern times it manifested itself in rural middle class loans. Peter Vail explains the circularity of loan-making and the ceiling it put on farmed income below. Importantly, this ceiling was not just economic, but also composed of social bounds, as the relationship between financial debt (borrowing money to plant crops) and social debt (alliances with those socially above you), in a very hierarchical society becomes quite complex. The "tradition" of the culture, and in many ways the nature of its paid social "respect" is also tied to financial debt, in the form of patronage. This is something to understand when thinking about the financial boon of local fighting itself. In a kaimuay the young fighter is given room and board, is trained almost as an adoptive son in a large family of other fighters, given skills developed in the gym not unlike a guild of knowledge, and is presented the opportunity to fight and make expense-free income that far, far exceeds that of his farming family, and there is a sort of infinite social debt and obligation as part of this relationship that is woven into the culture. Today these Muay Thai obligations are reified in legal contracts, but they run deep into its practices & history. Peter Vail on the Cycle of Rural Loaned Money The Fighter and the Average Worker I'm working from the low-end of Vail's estimates. If I project out his numbers to 7 months for the year (local fighting is seasonal falling to the patterns of planting and harvest) we end up with a broad picture like this. Even if Vail's 1,000 baht a fight estimates proved high for other regions beyond Khorat, there is enough play in these numbers to support the strenuous contrast. The average annual village worker in Thailand could save 440 baht (understood in the cycle of borrowings in Vail's description above). A local fighter could conceivably per capita outpace that to an enormous degree. Remember the data in question may not be precise, nor Vail's local fighter estimates. It just gives enough context for us to understand that what was driving local fighting in the provinces was not merely some unlikely strike-it-rich, become-a-star-in-Bangkok daydream. It was rather a quite robust and perfectly achievable fighting custom which outstripped the subsistence culture of farming and debt, which reached back for centuries. Gambling on ring sport seems to have very old antecedents possibly reaching back to the Indianization of Southeast Asia well over 1,000 years ago. In fact, one could imagine that the fight and festival gambling custom of Thailand's countryside developed in parallel to its subsistence farming practices, which themselves were defined by social bonds of patronage and social debt. Ring fighting among the youth of rural Thailand maybe seen less as something that the farming poor were forced to do, and more a dimension of the rural economy itself, the flow-back of moneys into the festival markets and the traditions of ring masculinity performance which characterized rural Thai identity. They were perhaps less supplemental income practices, and more co-evolved traditions or customs folded into larger practices of patronage and debt, tied to the rice harvest itself (and seasonal patterns of warfare, which were also tied to planting and harvest). Leaving aside the ethical criticism or moral rightness of these practices, understood within an economy of selves, rural-regional fighting in the 1990s made up a substantial avenue for social mobility (progression towards financially improving urban environments, the possibility of saved income, even the increased opportunity for education, which had to be paid for), and was woven into the rural culture & economy itself. The above paints a picture of the self-sustaining economic benefits of provincial fighting alone. There is no need to look to Bangkok for its motivation. But, if you look at Golden Age Muay Thai economics the picture gets even more stark. Below are average fight pay (after the 50% cut giving to the gym), of a few fighters we informally surveyed. These numbers are extremely ballpark, as fighter pay varied quite a bit depending on the stage of career (two fighters told us that the their first Lumpinee fight pay was only 2,500 baht, for instance), star power and at the higher levels, match-up. These are just "what did you make on your average fight" numbers, and memories could vary. Using the same 1994 data (Vail) one can see how even a lower level stadium fighter in an average fight far outstrips what the average Bangkok worker in a month could save. They are not even in the same economic worlds, and becoming a Bangkok laborer at this time was a significant draw to provincial Thailand. Provincial workers streamed into Bangkok due to the economic boom. Stadium fighters in the Golden Age of Muay Thai were towers above the average Bangkok worker, on a month to month basis. And this leaves out the very significant motivations of fame, social respect and idealized hypermasculinity that ring fighting provides. This can be seen as the "hoop dreams" aspect of the equation, but it's important to understand that at the systematic level the economics of Bangkok stadium fighting folded upon the already robust economics of local fighting in the provinces, when compared to the potential for laborers to save money beyond their expenses. We can leave aside the peak fight kaduas like Namkabuan's 250,000 baht, Kaensak's 380,000 baht, Karuhat's 240,000 baht, among so many others at the peak of the sport. At the level of the average fighter, the active participant in the scene, in the Golden Age of Muay Thai opportunity was economically profound when compared to rural Thailand.1 point

-

The purport of this short essay thread is not to question the ethics of the improvement of poverty conditions, nor to nostalgically wist back to agrarian times. It is to look more closely at the relationship between Thailand's Muay Thai and its likely unwritten rural heritage, and to think about the likely co-evolution of gambled ring fighting, local Thai culture (festivals, Buddhism & the wat, traditions of patronage & debt), and subsistence living. And it is to think about the deeper, systemic reasons why today's Muay Thai fighting and practices does not compare with those of Thailand's past. The fighters and the fights are just quite substantively not as skilled. This opens up not only a practical, but also an ethical question about what it means to preserve or even rejuvenate Thailand's Muay Thai. Much can be vaguely attributed to the dramatic strides that Thailand has made in reducing the poverty rate, especially among the rural population. This allows an all-to-easy diagnosis: "People aren't poor so they don't have to fight" which unfortunately pushes aside the substantive historical relationship between agrarian living (which has been largely subsistence living), and the social practices which meaningfully produced local fighting. It leaves aside the agency & meaningfulness of lives of great cultural achievement. If the intuition is right that gambled ring fighting and rural farming co-evolved not only over decades but possibly centuries, and that it produced a bedrock of skill and art development, then it is not merely the increase of rural incomes, but also the increased urbanization and wage-labor of Thailand's population overall. Changes in ways of Life. We may be in a state of vestigial rural Muay Thai, or at least the erosion of the way of life practices that generated the widespread fighting practices that fed Thailand's combat sport greatness, making them the best fighters in the world. At the most basic level, there are just vastly fewer fighters in Thailand's provinces today, a much shallower talent pool, and a talent pool that is much less skilled by the time it enters the National stadia. In the 1990s there were regularly magazine published rankings of provincial fighting well outside the Bangkok stadia scene. You can see some of these rankings in this tweet: The provinces formed a very significant "minor leagues" for the Bangkok stadia. It provided not only very experienced and developed fighters (many with more than 50 fights before even fighting in BKK), more importantly it also was the source of a very practiced development "lab-tested" of techniques, methods of fighting and training that generationally evolved in 100s of 1,000s of fights a year. Knowledge and its fighters also co-evolved. The richness of Thailand's Muay Thai is found in its variation and complexity of fighting styles, and this epistemic and experiential tapestry derived from the breadth of its fighting, not only at its apex in the Golden Age rings of Bangkok. Bangkok fighting was merely the fruit of a very deep-rooted tree. If we are to talk about the heritage of Thailand's Muay Thai and think about how to preserve some of what has become of Thailand's great art, especially as its National stadia start bending Muay Thai to the tourist and the foreign fighter, and less for and of Thais, seeking to stabilize its decline with foreign interest and investment, it should be understood significantly rooted in the very rural, subsistence ways of life that modernity is seeking to erase. And if these ways are too completely erased, so too will the uniqueness and efficacy of Muay Thai itself be impaired or even lost. We need to look to the social forms which generated the vast knowledge and practices of Thailand's people, as we pursue the economic and emotional benefit in modern progress, finding ways to support and supplement those achieved ways of being at the local and community level. The aesthetics, the traditions, the small kaimuay. The festival. Thinking of Muay Thai as composed of a social capital and an embodied knowledge diversely spread among all its practitioners, including its in-person fans, the endless array of small gyms, the infinity of festivals and their gambling rings, and the traditional ways of life of Muay Thai itself must be regarded as the vessel for Muay Thai's richness and greatness. And much of this resides in the provinces. No longer is it the great contrast between what a local fighter can win and the zero-sum of a farming life burdened with debt which can drive the growth of the art and sport, but we must recognize how much the form of fighting grew out of that contrast and seek to preserve the aspects of the social forms that anchor Muay Thai itself, which co-evolved with agrarian life. Muay Thai must be subsidized. Not only financially, but ethically and spiritually. And this has very little to do with Bangkok which has turned its face toward the International appetite.1 point

-

Cannot speak about Tiger as I don't know it as its a big camp and haven't been around it. I do know Silk. It's a pretty nice camp with a traditional Thai training aspect, and also Western friendly orientation. The training is hard, everyone is friendly. It seems like a great place for a long term investment.1 point

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

.thumb.jpg.723d772fd0407ec9ce090c692de37cff.jpg)