Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 01/02/2022 in all areas

-

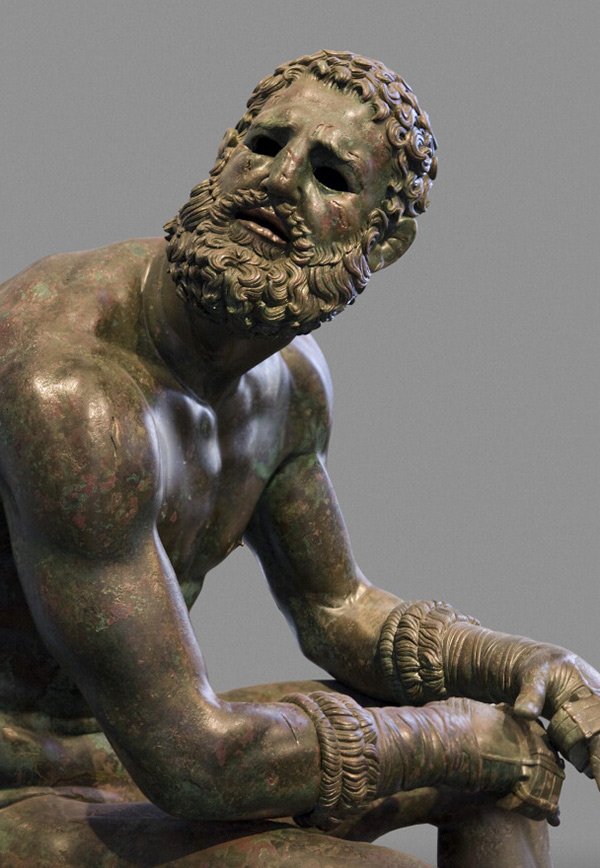

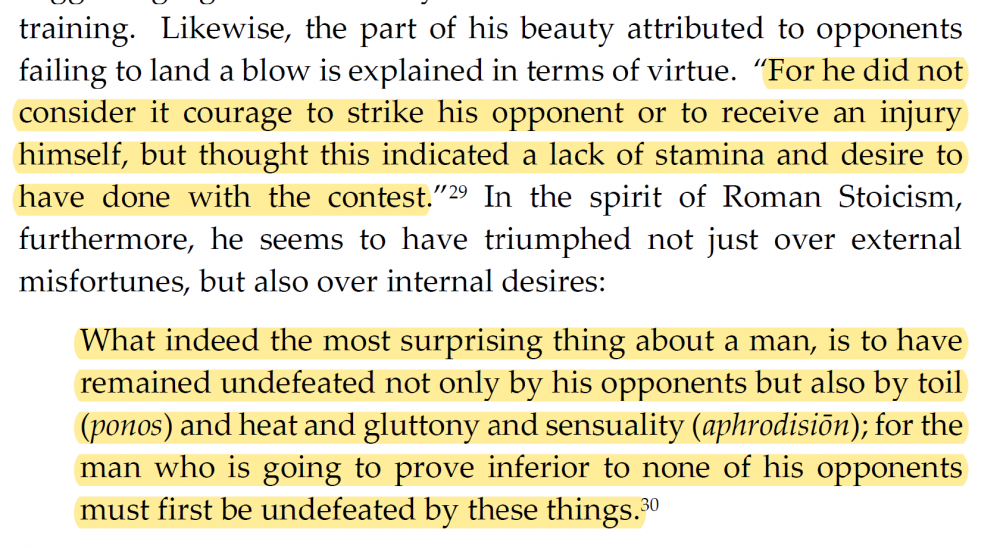

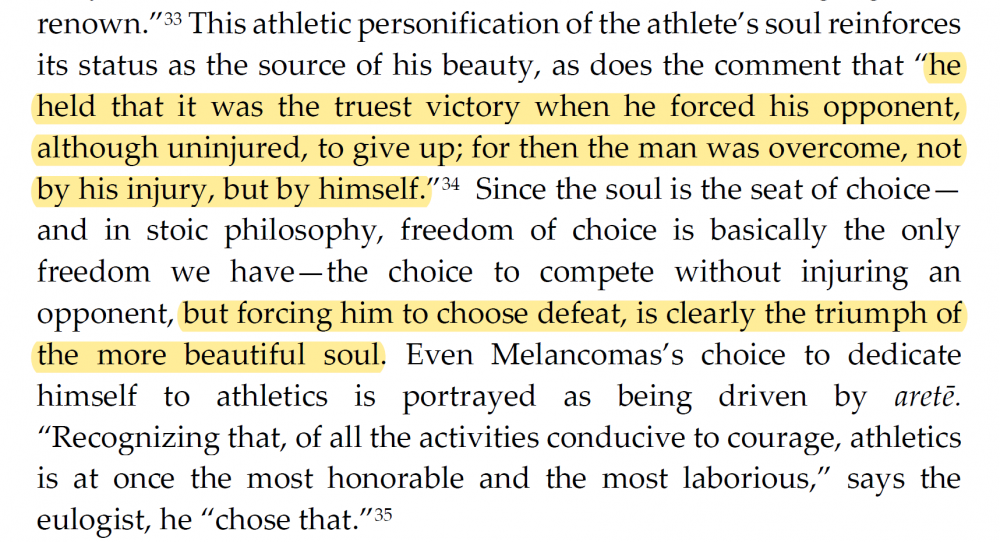

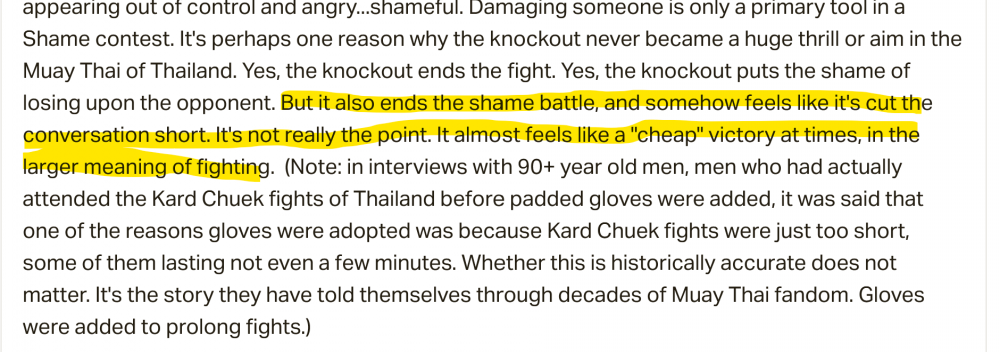

The famed trainer of Mike Tyson Cus D'Amato had a spectacular theory on what made fighters tired. Fear: “Fear is the greatest obstacle to learning in any area, but particularly in boxing. For example, boxing is something you learn through repetition. You do it over and over and suddenly you’ve got it. …However, in the course of trying to learn, if you get hit and get hurt, this makes you cautious, and when you’re cautious you can’t repeat it, and when you can’t repeat it, it’s going to delay the learning process…When they…come up to the gym and say I want to be a fighter, the first thing I’d do was talk to them about fear…” “The next thing I do, I get them in excellent condition….Knowing how the mind is and the tricks it plays on a person and how an individual will always look to avoid a confrontation with something that is intimidating, I remove all possible excuses they’re going to have before they get in there. By getting them in excellent condition, they can’t say when they get tired that they’re not in shape. When they’re in excellent shape I put them into the ring to box for the first time, usually with an experience fighter who won’t take advantage of them. When the novice throws punches and nothing happens, and his opponent keeps coming at him…the new fighter becomes panicky. When he gets panicky he wants to quit, but he can’t quit because his whole psychology from the time he’s first been in the streets is to condemn a person who’s yellow. So what does he do? He gets tired. This is what happens to fighters in the ring. They get tired. This is what happens to fighters in the ring. They get tired, because they’re getting afraid….Now that he gets tired, people can’t call him yellow. He’s just too “tired” to go on. But let that same fighter strike back wildly with a visible effect on the opponent and suddenly that tired, exhausted guy becomes a tiger….It’s a psychological fatigue, that’s all it is. But people in boxing don’t understand that.” …[Heller, 61] Trainer of one of the most vicious and entertaining knockout artists in modern boxing reveals how it is fear that can drive the knockout. One of the more inscrutable aspects of Thailand's traditional Muay Thai is that classically the knockout is seldom chased. There have been a handful of knockout artists, but the most esteemed fighters, legends of the sport were not knockout fighters. You'd see an elite fighter with 120 fights against top tier competition and maybe 10 or 12 KOs. In the West we thirst for the knockout. It's practically the entire entertainment goal of watching fighting. Highlight cut-ups are filled with starchings. It's the porn of fighting. Why do Thais - who by many measures make up some of the most skilled fighters in combat sports - not esteem the knockout? A large measure of this is that aggression is not viewed in the same way in Buddhistic Thailand as it is viewed in other cultures. It lacks self-control, a big aesthetic dimension of traditional Muay Thai is the exercise of control over oneself. But I turn to Cus D'amato's quote because I ran into a very interesting passage on the boxing of antiquity. The Greek orator Dio Chrysostom (c. 40 – c. 115 AD) is describing the virtues of the undefeated boxer Melancolmas. And one of the things that really struct me was that he claimed that knocking out an opponent was an act of cowardice. A fear of endurance: source notes linked Nearly 2,000 years ago in Hellenic Greece the same equation of fear, fatigue and aggression that Cus D'amato harnessed to produce the great Mike Tyson, was already understood, but fell in another light. The rule set of Greek boxing appears to have favored defensive fighting, and depending on your source, either consisted of a boxer fighting multiple opponents in succession, or fighting one opponent until collapse or relent. The fear and fatigue, the prospect of endurance was real and heightened. The praise for Melancomas was that he never took the easy way out and sought to end the fight, the test of himself, to end the fear by knocking his opponent out. It was rather through mastery of his opponent - and himself - that he would win. In the mouth of Chysostom we also find the aesthetic of Thailand's femeu fighter. He is the fighter who masters both himself and the space, and produces a victory out of the crumbling of his opponent's character. He chooses defeat, or collapses under the weight of its inescapability. When I read this I was quite struck, even feeling that I had never quite thought about this before, but somewhere in my mind it must have been registering that I had all the related thoughts that make this up, because I also stumbled on an old essay I wrote about how knockouts can feel like they have taken the "cheap" way out: you can read that essay here "Shame and Why Fighting Signals the Glue of What Holds Us Together" What's telling is that both Cus D'Amato and Chrysostom believe the same thing. Fear rises and the fighter is looking for a way out. Cus directs that fear into an instinct to end it all with a KO, Hellenistic Greece 2,000 years ago - and in many quarters of Thailand's traditional Muay Femeu greatness - counted the endurance of that fear, and its resolve through self control, and the control of the opponent as the greater art of fighting. This coincidence of fight philosophy came out of my research into the Terme Boxer, or The Boxer at Rest. A bronze sculpture of a boxer who has been bloodied and scarred by the endurance of his match. Contrary to the Greek classic ideal of the Apollonian athlete, depicted as standing, flawless and physically beautiful, this statue embraces the realism of the boxer 2,000 years ago. Scholars are not entirely sure why he is so realistically shown, but some feel that it was in answer to an over indulgence, an eros, in the image of the untouched boxer. Some feel that the sculpture depicts in inner beauty of a man facing that fear and enduring it, overcoming himself: What is interesting is that if the fighting arts / sports are to have culture value beyond the sheer visceral release of watching people get starched, some semblance of the idea that the knockout is an act of cowardice needs to take hold. Some sense in which "just wanting to end this thing" might be looking for a way out. We are conditioned to feel that the retreating fighter is the cowardly one, and we can certainly understand how that might be so. But perhaps best is to understand that there are two exits from the fear, one in disengagement, and the other in trying to cut it short through sudden violence. If a fighter is being forged like a blade, it's the lasting presence in the heat which creates the transformation and the perfection of the steel.1 point

-

Thanks for the reply. I agree with you on the buddhistic herritage of seing agression as weaknes, all though to me it seem more like agression out of control. And sometimes I feel we westerners have a bit too romantic and classic view on thai society and culture. All though I know you live it and know it well. Rodtang for instance, a huge name in the biggest stadiums in Thailand. Probably because of his agression and K.O abillity. And for Tyson, maybe it was his fear that made him so agressive, but it had to be power and technique landing those K.Os. He has become a very humble and smart man indeed, so naturaly he will be a great self critic. Thank you again for answering. Big fan1 point

-

Yes, very much so. Which brings us to perhaps a coincidence of how both Stoicism and Buddhism treat or have programs of self-control. I suspect that the real reason that Dio Chrysostom can speak to virtues that approximate scoring tendencies in traditional Muay Thai 2000 years later is that Thailand's Muay Thai is Buddhistic. So what we are really seeing is that Stoicism (and other Hellenic aesthetics) and Buddhism share a perspective on human affects, especially those of anger and aggression. Thanks for the links, I'll enjoy looking through them. Attached is the article: Athletic Beauty as Mimēsis of Virtue The Case of the Beautiful Boxer which talks about the prevalent social and philosophical attitudes around boxing in the era of The Terme Boxer. Athletic Beauty as Mimēsis of Virtue The Case of the Beautiful Boxer.pdf1 point

-

I’m looking forward to reading your blog post. I think you make a good point about not just hearing peoples feedback but also reacting appropriately and thoughtfully. I am going into business with another person and I’ve made it clear that poor behavior will get someone shown the door. I also want to be proactive instead of reactive to all types of problems within gyms. I mentioned to Sylvie above but in regards to sparring, I think I would like to have a regular class that teaches people how to spar safely and respectfully that covers all the common problems, including the ones that are specific to men and women sparring with one another. Communication, safety, controlling power, keeping ego in check, making sure to let them know that speaking to the coach about an issue is always an option, how to be a good training partner with other genders, etc. Doing an on boarding seems like it might be a proactive step to prevent problems.1 point

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

_Museu_Nacional_Rom_(Palau_Massimo)_Roma_(Vista_general).thumb.jpg.179a44581b5176b6af48cffe0e26b6e9.jpg)