All Activity

- Today

-

These are the descriptions from Peter Vail's dissertation which provided the low end estimates of rural fighting. As you can see his presents the possibility of even higher fighting income involving rural fighting. These numbers are from his research prior to his 1998 work. Using a low baseline of 1,000 baht per fight for 21 fights a year (21,000 baht clear of expenses), I built the statistical picture of an economy around local fighting. And...

-

The purport of this short essay thread is not to question the ethics of the improvement of poverty conditions, nor to nostalgically wist back to agrarian times. It is to look more closely at the relationship between Thailand's Muay Thai and its likely unwritten rural heritage, and to think about the likely co-evolution of gambled ring fighting, local Thai culture (festivals, Buddhism & the wat, traditions of patronage & debt), and subsistence living. And it is to think about the deeper, systemic reasons why today's Muay Thai fighting and practices does not compare with those of Thailand's past. The fighters and the fights are just quite substantively not as skilled. This opens up not only a practical, but also an ethical question about what it means to preserve or even rejuvenate Thailand's Muay Thai. Much can be vaguely attributed to the dramatic strides that Thailand has made in reducing the poverty rate, especially among the rural population. This allows an all-to-easy diagnosis: "People aren't poor so they don't have to fight" which unfortunately pushes aside the substantive historical relationship between agrarian living (which has been largely subsistence living), and the social practices which meaningfully produced local fighting. It leaves aside the agency & meaningfulness of lives of great cultural achievement. If the intuition is right that gambled ring fighting and rural farming co-evolved not only over decades but possibly centuries, and that it produced a bedrock of skill and art development, then it is not merely the increase of rural incomes, but also the increased urbanization and wage-labor of Thailand's population overall. Changes in ways of Life. We may be in a state of vestigial rural Muay Thai, or at least the erosion of the way of life practices that generated the widespread fighting practices that fed Thailand's combat sport greatness, making them the best fighters in the world. At the most basic level, there are just vastly fewer fighters in Thailand's provinces today, a much shallower talent pool, and a talent pool that is much less skilled by the time it enters the National stadia. In the 1990s there were regularly magazine published rankings of provincial fighting well outside the Bangkok stadia scene. You can see some of these rankings in this tweet: The provinces formed a very significant "minor leagues" for the Bangkok stadia. It provided not only very experienced and developed fighters (many with more than 50 fights before even fighting in BKK), more importantly it also was the source of a very practiced development "lab-tested" of techniques, methods of fighting and training that generationally evolved in 100s of 1,000s of fights a year. Knowledge and its fighters also co-evolved. The richness of Thailand's Muay Thai is found in its variation and complexity of fighting styles, and this epistemic and experiential tapestry derived from the breadth of its fighting, not only at its apex in the Golden Age rings of Bangkok. Bangkok fighting was merely the fruit of a very deep-rooted tree. If we are to talk about the heritage of Thailand's Muay Thai and think about how to preserve some of what has become of Thailand's great art, especially as its National stadia start bending Muay Thai to the tourist and the foreign fighter, and less for and of Thais, seeking to stabilize its decline with foreign interest and investment, it should be understood significantly rooted in the very rural, subsistence ways of life that modernity is seeking to erase. And if these ways are too completely erased, so too will the uniqueness and efficacy of Muay Thai itself be impaired or even lost. We need to look to the social forms which generated the vast knowledge and practices of Thailand's people, as we pursue the economic and emotional benefit in modern progress, finding ways to support and supplement those achieved ways of being at the local and community level. The aesthetics, the traditions, the small kaimuay. The festival. Thinking of Muay Thai as composed of a social capital and an embodied knowledge diversely spread among all its practitioners, including its in-person fans, the endless array of small gyms, the infinity of festivals and their gambling rings, and the traditional ways of life of Muay Thai itself must be regarded as the vessel for Muay Thai's richness and greatness. And much of this resides in the provinces. No longer is it the great contrast between what a local fighter can win and the zero-sum of a farming life burdened with debt which can drive the growth of the art and sport, but we must recognize how much the form of fighting grew out of that contrast and seek to preserve the aspects of the social forms that anchor Muay Thai itself, which co-evolved with agrarian life. Muay Thai must be subsidized. Not only financially, but ethically and spiritually. And this has very little to do with Bangkok which has turned its face toward the International appetite.

-

Cannot speak about Tiger as I don't know it as its a big camp and haven't been around it. I do know Silk. It's a pretty nice camp with a traditional Thai training aspect, and also Western friendly orientation. The training is hard, everyone is friendly. It seems like a great place for a long term investment.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

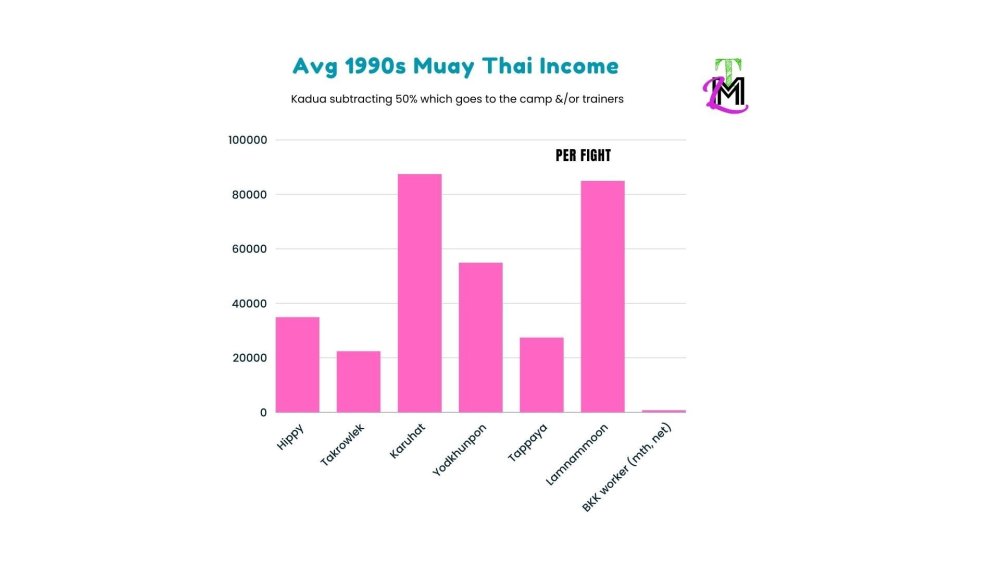

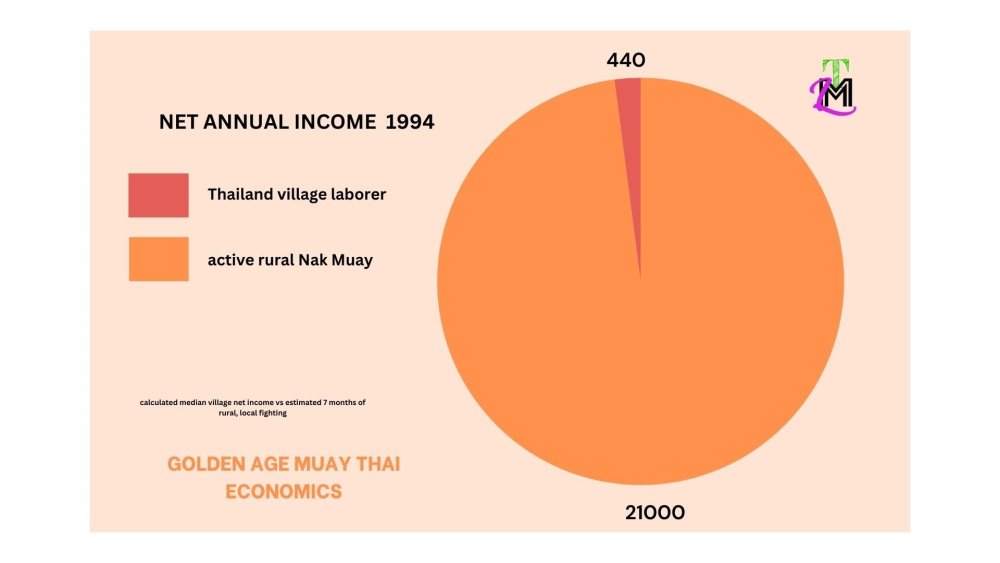

We tend to misunderstand Thailand when we think of individuals as discrete economic units. In a culture which is so heavily imbued with concepts of social debt, allegiance, patronage and hierarchy, the pure "individual" will always be a distortion, especially when thinking in terms of motivation. This being said, this piece is thinking about the economic motivations which shaped the prolific rural-regional fighting in Thailand's Golden Age of Muay Thai (1980-1995), mostly drawing on data and descriptions from Peter Vail's 1998 dissertation on Thailand's Muay Thai: Violence and Control: Social and Cultural Dimensions in Boxing, which I'm reading through for a second time now, the first being many years ago when we first moved to Thailand. One of the things I'm moving away from is the noted way in which Thailand's Muay Thai is characterized principally by its fights in the Bangkok National Stadia, which until recently held the international facing standard for its excellence as an art and sport. Muay Thai has been defined largely by its Rajadmnern and Lumpinee stadium example. Drawing back, it is meaningful perhaps to look beneath these high-profile fights and into the fabric which makes Thailand's Muay Thai like no other fighting art in the world: an historically persistent, vast rural-regional fighting practice and celebration, something which the economics of local fighting in Thailand in the 1990s sheds light on. In the larger frame, Muay Thai has been profoundly and prolifically fought throughout the provinces in Thailand (and Siam before that), intimately woven into its festival traditions for not only decades, but perhaps centuries. It has likely been part of its lasting agrarian culture, turning with the plantings and harvests, closely connected to the wat (Buddhist temple) and community, potential for millennia. It has an unwritten rural and regional heritage. And it has been this heritage and its widespread practice that has fed the stadia scene in the Capital for the last 100 years. Peter Vail is careful to point out that this robust fighting culture is not so much the case of a "hoop dreams" aim of long-shot stardom and life changing income, but rather one of a much closer, local practice. By the mid-1990s, with the Golden Age of Thailand's Muay Thai arguably coming to its close in the National stadia, rural, festival and regional Muay Thai was a very significant income source for the subsistence rural farming family, even for a modest, local fighter. The data Vail presents is from a 1994 survey, whose detailed accuracy may be question, but which also helps bring into broad picture the relative per capital wealth by region, and by urban and village groupings. "Savings" is qualified by the subtraction of expenses from income. Urban, more wage-oriented living was by far the more financially viable, with the best prospects in Bangkok. But even an average, non-exceptional fighter in local, festival fighting would in a single month - based on Vail's personal investigation, I believe primarily in Khorat - a very significant portion (a competitive sum) of even the annual savings that were possible of a Bangkok worker. (This graphic is based on Vail's somewhat conservative estimate that a local fighter could earn 3,000 baht fighting 3x a month in kadua fight pay alone - 1,000 baht a fight "take home" after a 50% cut taken by the gym). Because a fighter lives at the gym and has all his living expenses taken care of by the gym, potentially all of this income could clear expenses. This is leaving aside any income from fight gambling, tipouts from gamblers, or fighting in higher level local fights which would pay more. It's just an active, average rural-regional fighter in the mid-1990s. This would far outpace any of the annual totals of village labor averages in any of the four regions. In order to appreciate the economics of rural farming - and I certainly am no expert in this, only relating to the material - it seems important to understand that this is a subsistence way of life that somewhat systematically traded the possibility of increased income for the stability of loaned insurance against crop failures. Farming can be unpredictable, especially in the Northeast of Thailand which depends heavily on weather patterns as it does not irrigate from large rivers or lakes. Exchanging possible future gain for season-by-season stability builds in subsistence ways of life, and with them social stratification. This pattern goes quite far back in Siam to indentured labor, and farming practices that have been compared, perhaps with mixed accuracy, to Medieval fiefdoms, but in modern times it manifested itself in rural middle class loans. Peter Vail explains the circularity of loan-making and the ceiling it put on farmed income below. Importantly, this ceiling was not just economic, but also composed of social bounds, as the relationship between financial debt (borrowing money to plant crops) and social debt (alliances with those socially above you), in a very hierarchical society becomes quite complex. The "tradition" of the culture, and in many ways the nature of its paid social "respect" is also tied to financial debt, in the form of patronage. This is something to understand when thinking about the financial boon of local fighting itself. In a kaimuay the young fighter is given room and board, is trained almost as an adoptive son in a large family of other fighters, given skills developed in the gym not unlike a guild of knowledge, and is presented the opportunity to fight and make expense-free income that far, far exceeds that of his farming family, and there is a sort of infinite social debt and obligation as part of this relationship that is woven into the culture. Today these Muay Thai obligations are reified in legal contracts, but they run deep into its practices & history. Peter Vail on the Cycle of Rural Loaned Money The Fighter and the Average Worker I'm working from the low-end of Vail's estimates. If I project out his numbers to 7 months for the year (local fighting is seasonal falling to the patterns of planting and harvest) we end up with a broad picture like this. Even if Vail's 1,000 baht a fight estimates proved high for other regions beyond Khorat, there is enough play in these numbers to support the strenuous contrast. The average annual village worker in Thailand could save 440 baht (understood in the cycle of borrowings in Vail's description above). A local fighter could conceivably per capita outpace that to an enormous degree. Remember the data in question may not be precise, nor Vail's local fighter estimates. It just gives enough context for us to understand that what was driving local fighting in the provinces was not merely some unlikely strike-it-rich, become-a-star-in-Bangkok daydream. It was rather a quite robust and perfectly achievable fighting custom which outstripped the subsistence culture of farming and debt, which reached back for centuries. Gambling on ring sport seems to have very old antecedents possibly reaching back to the Indianization of Southeast Asia well over 1,000 years ago. In fact, one could imagine that the fight and festival gambling custom of Thailand's countryside developed in parallel to its subsistence farming practices, which themselves were defined by social bonds of patronage and social debt. Ring fighting among the youth of rural Thailand maybe seen less as something that the farming poor were forced to do, and more a dimension of the rural economy itself, the flow-back of moneys into the festival markets and the traditions of ring masculinity performance which characterized rural Thai identity. They were perhaps less supplemental income practices, and more co-evolved traditions or customs folded into larger practices of patronage and debt, tied to the rice harvest itself (and seasonal patterns of warfare, which were also tied to planting and harvest). Leaving aside the ethical criticism or moral rightness of these practices, understood within an economy of selves, rural-regional fighting in the 1990s made up a substantial avenue for social mobility (progression towards financially improving urban environments, the possibility of saved income, even the increased opportunity for education, which had to be paid for), and was woven into the rural culture & economy itself. The above paints a picture of the self-sustaining economic benefits of provincial fighting alone. There is no need to look to Bangkok for its motivation. But, if you look at Golden Age Muay Thai economics the picture gets even more stark. Below are average fight pay (after the 50% cut giving to the gym), of a few fighters we informally surveyed. These numbers are extremely ballpark, as fighter pay varied quite a bit depending on the stage of career (two fighters told us that the their first Lumpinee fight pay was only 2,500 baht, for instance), star power and at the higher levels, match-up. These are just "what did you make on your average fight" numbers, and memories could vary. Using the same 1994 data (Vail) one can see how even a lower level stadium fighter in an average fight far outstrips what the average Bangkok worker in a month could save. They are not even in the same economic worlds, and becoming a Bangkok laborer at this time was a significant draw to provincial Thailand. Provincial workers streamed into Bangkok due to the economic boom. Stadium fighters in the Golden Age of Muay Thai were towers above the average Bangkok worker, on a month to month basis. And this leaves out the very significant motivations of fame, social respect and idealized hypermasculinity that ring fighting provides. This can be seen as the "hoop dreams" aspect of the equation, but it's important to understand that at the systematic level the economics of Bangkok stadium fighting folded upon the already robust economics of local fighting in the provinces, when compared to the potential for laborers to save money beyond their expenses. We can leave aside the peak fight kaduas like Namkabuan's 250,000 baht, Kaensak's 380,000 baht, Karuhat's 240,000 baht, among so many others at the peak of the sport. At the level of the average fighter, the active participant in the scene, in the Golden Age of Muay Thai opportunity was economically profound when compared to rural Thailand.

- Yesterday

-

verloren joined the community

- Last week

-

Billy B started following 3 month camp

-

Hi all I’m looking to come out to Thailand for 3 months or longer and am looking to to train while I’m here I have no previous experience but it’s something I’ve always wanted to do I’ve currently been looking at Silk mauy Thai and Tiger mauy Thai any and all information or advice would be much appreciated. cheers Billy

-

Billy B joined the community

-

udangasammanis changed their profile photo

-

udangasammanis joined the community

-

Vino79908 joined the community

-

Link Vao W88 joined the community

-

LargoW joined the community

-

Amon ra joined the community

- Earlier

-

Ringer started following Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

Ringer joined the community

-

twicsybuyinstagramlikes joined the community

-

Komal Ahuja joined the community

-

More footnoting. Peter Vail in his 1998 dissertation sketching out a socio-religious basis for gambling, and Muay Thai gambling in particular, as an aspect of masculinity and charisma. See also this piece on Peter Vail's comparison of Muay Thai Masculinity to the Monk and the Nakleng (gangster): Thai Masculinity: Postioning Nak Muay Between Monkhood and Nak Leng – Peter Vail

-

One of the most confused aspects of Western genuine interest in Thailand's Muay Thai is the invisibility of its social structure, upon which some of our fondest perceptions and values of it as a "traditional" and respect-driven art are founded. Because it takes passing out of tourist mode to see these things they remain opaque. (One can be in a tourist mode for a very long time in Thailand, enjoying the qualities of is culture as they are directed toward Westerners as part of its economy - an aspect of its centuries old culture of exchange and affinity for international trade and its peoples.). If one does not enter into substantive, stakeholder relations which usually involve fluently learning to speak the language (I have not, but my wife has), these things will remain hidden even to those that know Thailand well. It has been called, perhaps incorrectly, a "latent caste system". Thailand's is a patronage culture that is quiet strongly hierarchical - often in ways that are unseen to the foreigner in Muay Thai gyms - that carries with it vestigial forms of feudal-like relationships (the Sakdina system) that once involved very widespread slavery, indentured worker ethnicities, classes and networks of debt (both financial and social), much of those power relations now expressed in obligations. Westerners just do not - usually - see this web of shifting high vs low struggles, as we move within the commercial outward-facing layer that floats above it. In terms of Muay Thai, between these two layers - the inward-facing, rich, traditional patronage (though ethically problematic) historical layer AND the capitalist, commerce and exchange-driven, outward-facing layer - have developed fighter contract laws. It's safe to say that before these contract laws, I believe codified in the 1999 Boxing Act due to abuses, these legal powers would have been enforced by custom, its ethical norms and local political powers. There was social law before there was contract law. Aside from these larger societal hierarchies, there is also a history of Muay Thai fighters growing up in kaimuay camps that operate almost as orphanages (without the death of parents), or houses of care for youth into which young fighters are given over, very much like informal adoption. This can be seen in the light of both vestigial Thai social caste & its financial indenture (this is a good lecture on the history of cultures of indentured servitude, family as value & debt ), and the Thai custom of young boys entering a temple to become novice monks, granting spiritual merit to their parents. These camps can be understood as parallel families, with the heads of them seen as a father-like. Young fighters would be raised together, disciplined, given values (ideally, values reflected in Muay Thai itself), such that the larger hierarchies that organize the country are expressed more personally, in forms of obligation and debt placed upon both the raised fighter and also, importantly, the authorities in the gym. One has to be a good parent, a good benefactor, as well as a good son. Thai fighter contract law is meant to at bare bones reflect these deeper social obligations. It's enough to say that these are the social norms that govern Thailand's Muay Thai gyms, as they exist for Thais. And, these norms are difficult to map onto Western sensibilities as we might run into them. We come to Thailand...and to Thailand's gyms almost at the acme of Western freedom. Many come with the liberty of relative wealth, sometimes long term vacationers even with great wealth, entering a (semi) "traditional" culture with extraordinary autonomy. We often have choices outside of those found even in one's native country. Famously, older men find young, hot "pseudo-relationship" girlfriends well beyond their reach. Adults explore projects of masculinity, or self-development not available back home. For many the constrictures of the mores of their own cultures no longer seem to apply. When we go to this Thai gym or that, we are doing so out of an extreme sense of choice. We are variously versions of the "customer". We've learned by rote, "The customer is always right". When people come to Thailand to become a fighter, or an "authentic fighter", the longer they stay and the further they pass toward that (supposed) authenticity, they are entering into an invisible landscape of social attachments, submissions & debts. If you "really want to be 'treated like a Thai', this is a world of acute and quite rigid social hierarchies, one in which the freedom & liberties that may have motivated you are quite alien. What complicates this matter, is that this rigidity is the source of the traditional values which draws so many from around to the world to Thailand in the first place. If you were really "treated like a Thai", perhaps especially as a woman, you would probably find yourself quite disempowered, lacking in choice, and subject only to a hoped-for beneficence from those few you are obligated to and define your horizon of choice. Below is an excerpt from Lynne Miller's Fighting for Success, a book telling of her travails and lessons in owning the Sor. Sumalee Gym as a foreign woman. This passage is the most revealing story I've found about the consequences of these obligations, and their legal form, for the Thai fighter. The anecdote of the disorienting photo op meet is exemplar. While extreme in this case, the general form of obligations of what is going on here is omnipresent in Thai gyms...for Thais. It isn't just the contractual bounds, its the hierarchy, obligation, social debt, and family-like authorities upon which the contract law is founded. The story that she tells is of her own frustrations to resolve this matter in a way that seems quite equitable, fair to our sensibilities. Our Western idea of labor and its value. But, what is also occurring here is that, aside from claimed previous failures of care, there was a deep, face-losing breech of obligation when the fighter fled just before a big fight, and that there was no real reasonable financial "repair" for this loss of face. This is because beneath the commerce of fighting is still a very strong hierarchical social form, within which one's aura of authority is always being contested. This is social capital, as Bourdieu would say. It's a different economy. Thailand's Muay Thai is a form of social agonism, more than it is even an agonism of the ring. When you understand this, one might come to realize just how much of an anathema it is for middle class or lower-middle class Westerners to come from liberties and ideals of self-empowerment to Thailand to become "just like a Thai fighter". In some ways this would be like dreaming to become a janitor in a business. In some ways it is very much NOT like this as it can be imbued with traditional values...but in terms of social power and the ladder of authorities and how the work of training and fighting is construed, it is like this. This is something that is quite misunderstood. Even when Westerners, increasingly, become padmen in Thai gyms, imagining that they have achieved some kind of authenticity promotion of "coach", it is much more comparable to becoming a low-value (often free) worker, someone who pumps out rounds, not far from someone who sweeps the gym or works horse stables leading horse to pasture...in terms of social worth. When you come to a relatively "Thai" style gym as an adult novice aiming to perhaps become a fighter, you are doing this as a customer attempting to map onto a 10 year old Thai boy beginner who may very well become contractually owned by the gym, and socially obligated to its owner for life. These are very different, almost antithetical worlds. This is the fundamental tension between the beauties of Thai traditional Muay Thai culture, which carry very meaningful values, and its largely invisible, sometimes cruel and uncaring, social constriction. If you don't see the "ladder", and you only see "people", you aren't really seeing Thailand.

-

AlanP started following Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu

-

Chor Hapayak Gym - still closed off to foreigners?

Snack Payback replied to riveranton's topic in Gym Advice and Experiences

He told me he was teaching at a gym in Chong Chom, Surin - which is right next to the Cambodian border. Or has he decided to make use of the border crossing? -

Leaving aside the literary for a moment, the relationship between "techniques" and style (& signature) is a meaningful one to explore, especially for the non-Thai who admires the sport and wishes to achieve proficiency, or even mastery. Mostly for pedagogic reasons (that is, acute differences in training methods, along with a culture & subjectivity of training, a sociological thread), the West and parts of Asia tend to focus on "technical" knowledge, often with a biomechanical emphasis. A great deal of emphasis is put on learning to some precision the shape of the Thai kick or its elbow, it's various executions, in part because visually so much of Thailand's Muay Thai has appeared so visually clean (see: Precision – A Basic Motivation Mistake in Some Western Training). Because much of the visual inspiration for foreign learned techniques often come from quite elevated examples of style and signature, the biomechanical emphasis enters just on the wrong level. The techniques displayed are already matured and expressed in stylistics. (It would be like trying to learn Latin or French word influences as found in Nabakov's English texts.) In the real of stylistics, timing & tempo, indeed musicality are the main drivers of efficacy. Instead, Thais learn much more foundational techniques - with far greater variance, and much less "correction" - principally organized around being at ease, tamachat, natural. The techne (τέχνη), the mechanics, that ground stylistics, are quite basic, and are only developmentally deployed in the service of style (& signature), as it serves to perform dominance in fights. The advanced, expressive nature of Thai technique is already woven into the time and tempo of stylistics. This is one reason why the Muay Thai Library project involves hour long, unedited training documentation, so that the style itself is made evident - something that can even have roots in a fighter's personality and disposition. These techne are already within a poiesis (ποίησις), a making, a becoming. Key to unlocking these basic forms is the priority of balance and ease (not biomechanical imitations of the delivery of forces), because balance and ease allow their creative use in stylistics.

-

Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu started following Chor Hapayak Gym - still closed off to foreigners?

-

Wangchannoi is no longer at the gym, he has moved to a small gym in Cambodia. Bangsaen had indicated westerners were welcome to train with the gym, but it Isa true Thai gym and ther aren't many options nearby so staying at the gym seems most likely the only accommodation if you intend to stay beyond a couple days. They don't have social media in English, so I'd recommend just going to the gym and pleading your case: https://maps.app.goo.gl/4N8wMms2sU3xkeBbA

-

When we spoke to them during our filming they at first said that they were closed to non-Thais, but a little while later they changed their mind and said they were open to it, but that if you trained there you could not come and go, ie, you would have to treat it like a camp, and train in the restricted Thai fashion. I think this would be very difficult to manage if you did not speak Thai, to be honest about it. Most western friendly Thai gyms have enough English to get by, but Chor Hapayak is very, very Thai, at least as we encountered it. Also of note, believe that Wangchannoi is no longer a trainer there, though Bangsaen Tor. Kotsan (who is also in the Muay Thai Library) still is.

-

Further afield, here is a discussion of Thailand's Muay Thai in terms of the Aesthetics of Deleuze, especially as it relates to the Western student/fighter in Thailand. This also is a grasping of aesthetics as it is distinguished from ethics, and addresses the idea of Living One's Life as a Work of Art.

-

This thesis of the aesthetic is perhaps most telling in its (very rare) failure, in the two losses of Samart Payakaroon, the acknowledged greatest fighter of Thailand's Muay Thai. Below are the two fights, he is not at his peak as a fighter in both cases. Unfortunately there is no preserved video from his prime, when he was a regular stadium fighter before he left for boxing. Both of these fights are interesting from the aesthetic question, for you get to see Samart shift into aesthetic attempts to take flight over difficulties...in these cases to have such a flight fail. In the negative you can imagine how such styles must have operated at this time of true greatness, of which we only have eye-witness report: Dieselnoi vs Samart Wangchannoi vs Samart In the negative you can also see Karuhat's failed attempt to climb to victory using the aesthetics of his style in his 3rd fight vs Wangchannoi (a fight he to this day felt like he won), or his early fight vs Hippy. In these negative examples you can see the role of style, as it doesn't-quite-cross the chasm. Karuhat vs Wangchannoi After two losses to Wangchannoi Karuhat really set his mind to winning the third fight vs the much bigger Wangchannoi. You can visibly see Karuhat style climbing on him, seemingly to real effect, but the judges ruled it just wasn't enough. And Karuhat vs Hippy This fight is quite extraordinary, very early in Karuhat's career before he fully matured, in that Karuhat seeks to style climb on Hippy, and Hippy style climbs right back at him. What I mean by "style climb" in the above are the ways in which Thailand's traditional Muay Thai rewards stylistic displays of being above or beyond the fight, aspects of which are culturally coded (for instance certain body positions (ruup), or qualitative tempos, or musicalities. You can read about the role of dominance in the traditional form of the sport here: The Essence of Muay Thai: 6 Core Aspects Which Make it What it Is. More obviously fighters which employ stylistics are of the more Muay Femeu (technical, artful) variety, though there are distinct stylistics to its counterpart, Muay Khao.

-

This beautiful quote from The Magician's Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction uncovers a powerful observation on the function of style for an artist. What is in question is the way in which Nabokov comes to what really are aporias - difficult crossings - in his writing, discussions of the roots of knowledge or of ethics. It is the particular way in which Nabokov can dive down into some of the most beautiful writing in the English language, only to then surface into parodies of literary styles, or even almost parody of himself. The quote places the leverage point at the level of the difficulty of the answer. What this opens up is a separable understanding of the uses of aesthetics, of style, itself. The way in which style can be used to overcome doubts, or certain impassible gaps, an aesthetic solution to the next moments of living. It is as if one's style, if fully invested, can briefly give you wings to cross short chasms until you can land on the other side, when the style becomes more grounded, has more footing. What comes to mind, if we allow ourselves to leave literature and enter the traditional Muay Thai ring is the fighting style of Karuhat Sor. Supawan, who may be the greatest stylist of Thai history. What the stylistics of traditional Muay Thai can teach us of the pragmatic role of style is the very firm-footed nature of these brief flights into personalized aesthetics. When you study Karuhat's fights - you can find 32 of them here - especially as he matures as a fighter, you can locate very contested sections of fights where he will almost inexplicably pass into style. He may or may not be scoring, but it is the weightlessness of his ascent, at those very times that feel the most difficult, most uncrossable, that displays the power of style. It is as if, when you do not know what is next, what can be done, you pass into style, almost as if humming the bars of a song you have forgotten the words to, passing into pure melody. And, once alighting on the other side, you return again to the lyrics. Karuhat's style has many components, techniques, pieces, bars. His side shuffle along the rope, the interruptive trip-out, the snake-charmer's sway, the delay on an already released kick, the syncopated swing step, short popping crosses or hooks, all techniques in a deepseated personal melody. And at a time of great crisis he can pass into style alone. This Muay Thai Scholar video will give you some reference to elements of Karuhat's Style: While I would consider Karuhat Thailand's greatest stylist, I believe this aesthetic rule, the pragmatism of Style can be found throughout the legendary fighters of Thailand's Golden Age: from Samson's drumming dern, smothering tempos, to Samart's deer-like escapes, nonchalance and unexpected power; from Dieselnoi's early round, wading-in, spider-like defensive rhythms, to Wangchannoi's stubborn heavy hand pressures. Samart, widely considered the GOAT of the sport is a great case in point, himself a great stylist. In fact I believe you can see this aspect of aesthetics in the face of difficulty especially in his two notable loses, against Dieselnoi and Wangchannoi, where you can if you watch closely his appeal to style, which does not quite carry him over - a proof in the negative. What is most interesting about Thailand's Muay Thai is that while it is one of the more violent sports in the world, it simultaneously is an art, and this dimension of aesthetics is what shows itself in the efficacy of performance. Style, in brief wing-beats, can carry you across brief chasms of doubt, all the while remaining within the physically constrained grounds of an actual fight, full of real material dangers. The transcendent nature of Thailand's Muay Thai, as an art, resides in this aesthetic dimension, which made its Golden Age fighters the best fighters in the world. As Muay Thai changes, coming under the influence of more commercial, more casual (tourism driven) demands, it is losing its aesthetic dimension. Thai fighters less and less have recourse to individual styles which can guide them across difficulties. Vestigial aspects of Thai aesthetics still remain in the 5th round retreat, the emphasis on defense, the reward of balance, but fewer and fewer fighters have fully developed, personalized style - something also seen in the Thai principle of sanae (charm). The recourse to "techniques" (in particular increasingly memorized combinations), of which styles are more ideally composed, to carry one through difficulties, the dumbing down of styles into practiced singular strikes, is progressively sinking the sport into less expressive states, a movement which ultimately will rob it of its larger meaning and value to the world...its art. Muay Thai is in a certain sense, the literature of fighting. This opens up important questions as to the relationship between the study of techniques, and the development of styles. The Magician's Doubts quote at top also carries another quality of style, which is that when the answer is easy style can become simply "signature", almost a kind of excess. We see this in actors, perhaps like Di Nero whose inimical style in youth became caricature in older age, how a fighter like Saenchai, whose subtle effects carried him through the stadium ranks, then became pure signature and show vs a pool of requisite non-Thais on Thai Fight, according to his late maturity. At its most ideal a fighter's style in a fight would perhaps weave between these poles, ascending to style during a fight's greatest impasses (witness Ali's rope-a-dope or late-rounds shuffle), but also the signing of fights, in during its easier stretches, in displays of style, the author's signature. And in between these poles, the boots-on-the-ground fighting, by which leads are fashioned or protected, a pragmatism of two bodies in conflict caught in the context of twin aesthetic freedoms.

-

twicsyfreeinstagramlikes changed their profile photo

-

How much did it cost you to train at the gym? this sounds like an amazing experience. Definitely wanna go there.

-

riveranton started following Chor Hapayak Gym - still closed off to foreigners?

-

Thanks to Sylvie and Kevin, I've learned about Wangchannoi and I've been so impressed by his style of fighting. One of my goals this year is to train in Thailand, in particular with Wangchannoi at Chor Hapayak. But I had a few questions that I'd like to know in order to help me plan: - Is Chor Hapayak still closed off to foreigners? I've heard it's quite exclusive/not open to farang - Does anyone have an address or contact details that I can reach out to? In particular for privates with Wangchannoi or potentially booking general training sessions at the gym? - Does anyone have any knowledge about how the training is structured there? Thanks in advance.

-

Helpful Videos for Beginners

ChaiSL replied to Leto's topic in Patreon Muay Thai Library Conversations

Thanks for providing this. I am beginner as well been only training for about a few months and am looking to suscribe to the pattern to access some of these sessions. Just curious are there specific exercises or bag work drills or other things that the videos clearly lay out that we can practice or is it more the knowledge of the techniques and then we have to figure out how to put the techniques into practice? I also wanted to say thank you and Sylvie so much for putting this together. The videos I have watched of you guys on YouTube really put into perspective the real essence of the Muay Thai culture that I feel is sometimes lacking in the gym I train in here in North America. My gym I train at is good for training but I do not get the same kind of education about the philosophy, spirituality and ethics I get in some of your podcast videos so thank you. Are there any specifics videos on the library that you suggest that has learnings on the philosophy or spiritual side of Muay Thai from any of the legends or Krus. Thank you too much again, your work is great appreciated! -

Hi Warren It was very quiet when I was there. A few local guys and 2-4 foreigners but that can change and I'm sure this gym has got more popular. You can schedule privates for whenever you want. The attention to detail here is unbelievable and I highly recommend you train at this gym. In my experience, everyone was really good training partners and I learnt loads everyday.

- 3 replies

-

- 2

-

-

- coaches

- gym experience

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

You can look through my various articles which sometimes focuses on this: https://8limbsus.com/muay-thai-forum/forum/23-kevins-corner-muay-thai-philosophy-ethics/ especially the article on Muay Thai as a Rite. The general thought is that Thailand's traditional Muay Thai offers the world an important understanding of self-control in an era which is increasingly oriented towards abject violence for entertainment. There are also arguments which connect Muay Thai to environmental concerns.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

buymagicmushroomsomh changed their profile photo

-

Can anyone recommend any clinch fighters that were usually smaller than their opponents to study ? In the MTL or not.

-

Hi @TRTdoc I'm going to be in Thailand to train for 2-3 months and this gym has been recommended in this forum and elsewhere. Would it be safe to assume that the private lessons were between the 2 classes? Or where they after the 3pm session (or both)? Lastly, How many people were at the group classes? Thanks!

- 3 replies

-

- coaches

- gym experience

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

I was a student there for 2 years straight, the longest of any foreigner there. I loved it. I grew a lot, you chose well.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

.thumb.jpg.723d772fd0407ec9ce090c692de37cff.jpg)

.thumb.jpeg.77eb46029d1a4b88cb8d755d0889bdce.jpeg)