-

Posts

2,264 -

Joined

-

Days Won

500

Everything posted by Kevin von Duuglas-Ittu

-

some of the above is in reflection of years of this kind of intense training below. Sylvie really did train like few others in Thailand, full sessions at multiple gyms for many years...the Muay Thai Library was actually born out of this tendency of looking for the best training possible, but greatest influences, piecing it together. Part of this was coming to realize that the full kaimuay training quality of the Golden Age, what made great fighters of the past, no longer really really existed in Thailand, especially in terms of availability for a female fighter. Thailand's Muay Thai was fragmented so optimal training had to be fragmented and assembled. Sylvie and Phetjee Jaa training Sylvie training with Jee Jaa's family, probably an entire year of this, about 10 years ago. She would go over for a full session after her full session at Phetrungruang, her 3rd of the day. Sylvie's film about 9 years ago capturing the full day of training back then: and the article that went with it: short film – A Day of My Training – Love the Grind

-

The Anchors of Muay Thai Training We actually heard this years ago, at Phetjee Jaa's family gym, where Sylvie trained for a year. The anchor of training - once you know the language of Muay Thai, from most important to least: To anchor Clinch Run In stretches, all other things can be skipped, this is your foundation. Everyday. In the West everyone is obsessed about "techniques" (learning them, perfecting them, drilling them, making them "muscle memory"), its how the West perceives Muay Thai, (aesthetic) biomechanically. In Thailand, its clinch and run. There are real, efficacious reasons for this. I'll write about this later, but they involve the DNA of Thai fighting, drawing out energy management in long-wave patterns that breakdown short exchange or burst fighting, in both the Muay Khao and the Muay Femeu fighter. To Improve Spar Shadowbox These are just so important, because properly done they produce longevity play and creativity, the heartbeat of true fighting. It depends on your sparring partner, and you should have a few of course, but these two aspects of training are the primary paths to improvement. To maintain and build Bagwork Padwork Outside of Thailand there is a lot of emphasis on padwork, mostly because Thailand does padwork like nowhere else, and a lot of the signatures of "authenticity" by non-Thai coaches come from imitating or approximating Thai padwork. In all my time I've only seen two Westerners who actually "get" what's happening in high level Thai padwork, and they both hold pads in an idiosyncratic way, not "like a Thai". They digested the qualities through years in Thailand, and came up with their own expression of it. Kaensak told us, padwork is just to "charge the battery" before a fight, its traditionally not really used as a teaching mechanism, and certainly not a drilling combos mechanism, though lots of padholders have taken it in that direction. Largely though, padwork, once you know the language of Muay Thai, is in the bottom rung of importance, in my opinion. There is an exception to this, in that if you find an extraordinary padman who can develop rhythms and distance shaping, through a very high level of feel (padwork is about these things, not about strikes), this can be very significant and make big differences in fighters over time...but, on the other hand, if you have padmen who have little sensitivity toward these things, or push into styles that are not conductive to your own, padwork can be even detrimental, giving you space and rhythm that will not help you much in fights and probably will be counterproductive.

-

Muay Roid, the New Art People starting to question the weight bullying, and roids in Muay Thai. Weight bullying has been pretty endemic in Thailand's Muay Thai, in part because Westerners are just bigger physically (and have to be accommodated in the tourist commerce of the sport), in part because those size differences reflect real economic powers. What isn't talked about too much is that Thailand has also long been a roid holiday center, a place where people come to cycle on. Put the two together and you end up producing serious power differentials, especially if you restructure the rules and aesthetics to favor clash fighting. This also comes with the glorification of the "alpha" body, which also drives the internet versions of the sport. It should also be noted that some Thais themselves likely have caught onto some of this weight bullying, and have also started to try to go up in size as much as possible, not only to keep from being so weight bullied, but also to reach into higher weight classes.

-

Almost all fights in Thailand are technically "pro" under full trad, or entertainment rules. You likely are already skilled enough for your first fight (all things being equal), if your gym is adept at finding matches (it depends on your size too). But, you'd probably want to train a month to acclimate yourself, develop training calluses (not actual calluses, but mental and physical toughness) to make your first fight more digestible. First fights are mental whirlwinds, and the more acclimated your are, the more enjoyable they'll be.

-

A Test of Meksen Usually I could care less about ONE cards, but this Meksen vs Kana fight is very interesting, as Meksen has risked so much in joining ONE. She kind of have a somewhat protected kickboxing career in Europe (with some big wins), simply because the sport is fairly small, and made what seemed like a bid for what she felt was a highly coveted belt. She got involved in contract quicksand, the kind of which forced Iman Barlow into retirement, then was forced into the buzz saw of Phetjee Jaa...and then fighting UP in weight (which top fighters don't really like to do if they can avoid it) vs Buntan, a much less experienced by very capable, disciplined fighter. Meksen has a storied career of wins and in it not much experience with loss. If she loses to Kana that would make 3 losses in a row, which I imagine would be extremely difficult. Kana is a tough fighter who has some attacks off the pivot that could pose problems for Meksen's direct attacks. This is certainly a very meaningful fight for a fighter of Meksen's renown. I'm interested in how she handles it. The fight itself, I don't know. I'm not a fan of watching even the faux Muay Thai ruleset much (it takes a special fighter to make it interesting), and the kickboxing version even less, its just not made for me as an audience member. But, as a fan of female fighters there is very strong story here, bigger than even vs Phetjee Jaa I believe.

-

The Chinese Impact on Modern Siamese/Thai Culture Read this incredible description from 1855, and see just how "Chinese" Bangkok was well before the turn of the century. The rivers and canals were the life's blood of the city, and every liquid's edge was Chinese, pulsing with their culture, shops in Chinese. 200,000 in Bangkok alone then, most of them lining the waterfronts and tributaries. To understand Bangkok's Muay Thai one has to appreciate the intensity of the braiding of Siamese culture with Chinese commerce and culture, going back hundreds of years. This is not just an isolated China "town", the Capital was in many respects Chinese-driven economically. The history of the Chinese Bangkok Muay Thai promoter goes back to this anchorage. I've written about before how much the railroad changed Siam/Thailand, connecting hard to reach provinces to the capital 1900-1930, in terms of Muay Thai bringing provincial fighters in proximity to Capital fighting, mixing those styles, but before the railroad pulled the provinces closer to Bangkok, the arrival of the steamship in the mid-1850-60s, brought 100,000s of Chinese (and others) as emigrants to Siam, the flow of a huge workforce and commercial investment from abroad, burgeoning in the city and throughout its waterways and ports to the South.

-

Martial Influences from China One can make very broad assumptions about the likely cross pollination of mercenary martial influences upon Muay Thai (Boran), but seldom is there a specific example of possible influence. This is not direct evidence, but you have a grandson of a renown Fujian swordsman making his way to Songkla in Siam's South, doing battle against the Malay, to one day become a powerful Siamese figure. This is one account of literally 100,000s of Chinese who came to Siam in the 19th century, many of them settling into the South and becoming prominent in the culture. from A History of the Thai-Chinese, Pimpraphai Bisalputra

-

Thai Push Back Against Entertainment Muay Thai This Facebook posting, which reposts something written by a famous gym head in Thailand (and presumably deleted), after I believe a ONE Friday Night Fights where 5 Thais were KO'd. This is a growing sentiment, albeit a minority sentiment, regarding Entertainment Muay Thai which is basically designed for Western wins, in a Western aesthetic.

-

Preventing the KO in a Knockout Format Sylvie's 283rd fight, with her commentary we just put up. Just beautiful stuff. I kind of love how so many of the Entertainment Muay Thai shows are thirsting for KOs, especially by Westerners, but the show Sylvie loves actively works towards the opponent's health, and protects against the KO, despite being a "Knockout" show. Her overwhelmed opponent got to dig down into herself, get up, get up, get up, and then fight a dignifying 5th.

-

Sylvie Beating Size and Excellence Love this fight several years ago, Sylvie beating Thanonchanok giving up 6 kgs on the scale. Thanonchanok is probably the most decorated female fighter in Thai history, holding multiple World titles across several weight classes. 2 months after this fight Thanonchanok would fly to Japan and win yet another World title. Just took a look at the fight again.

-

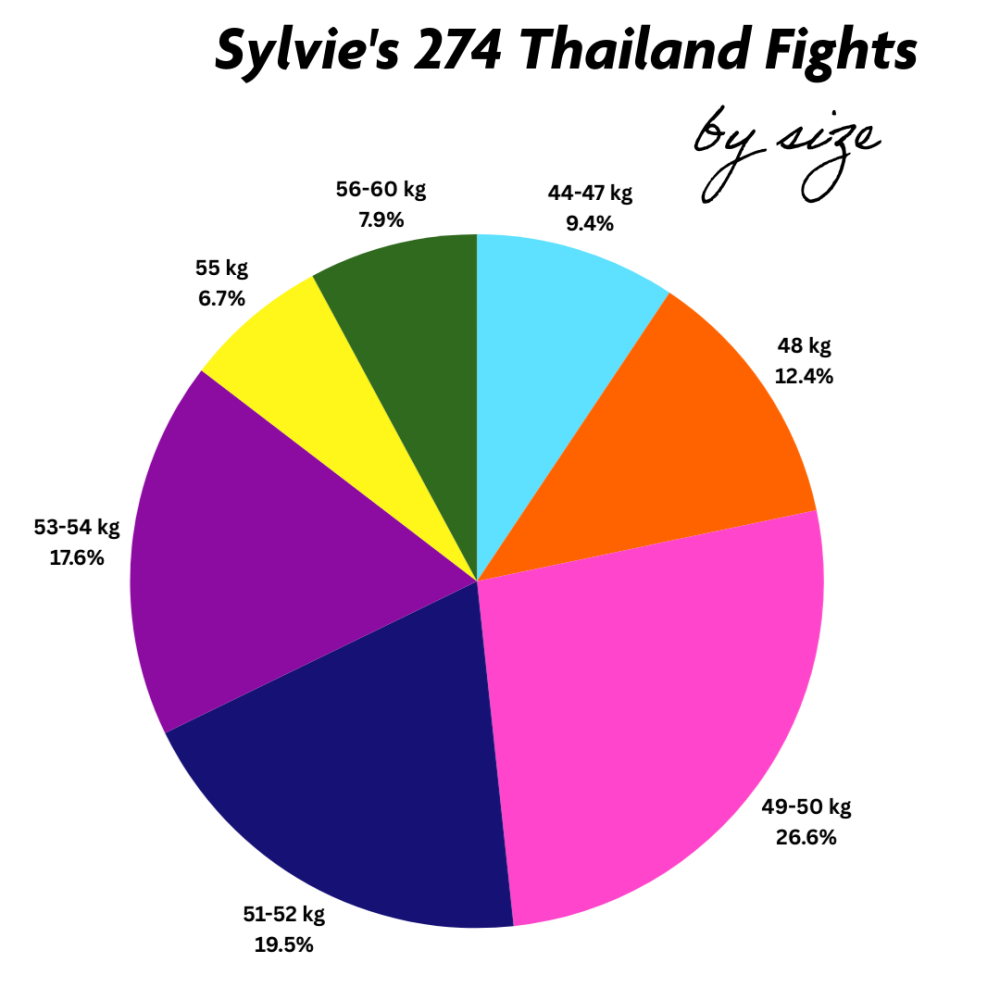

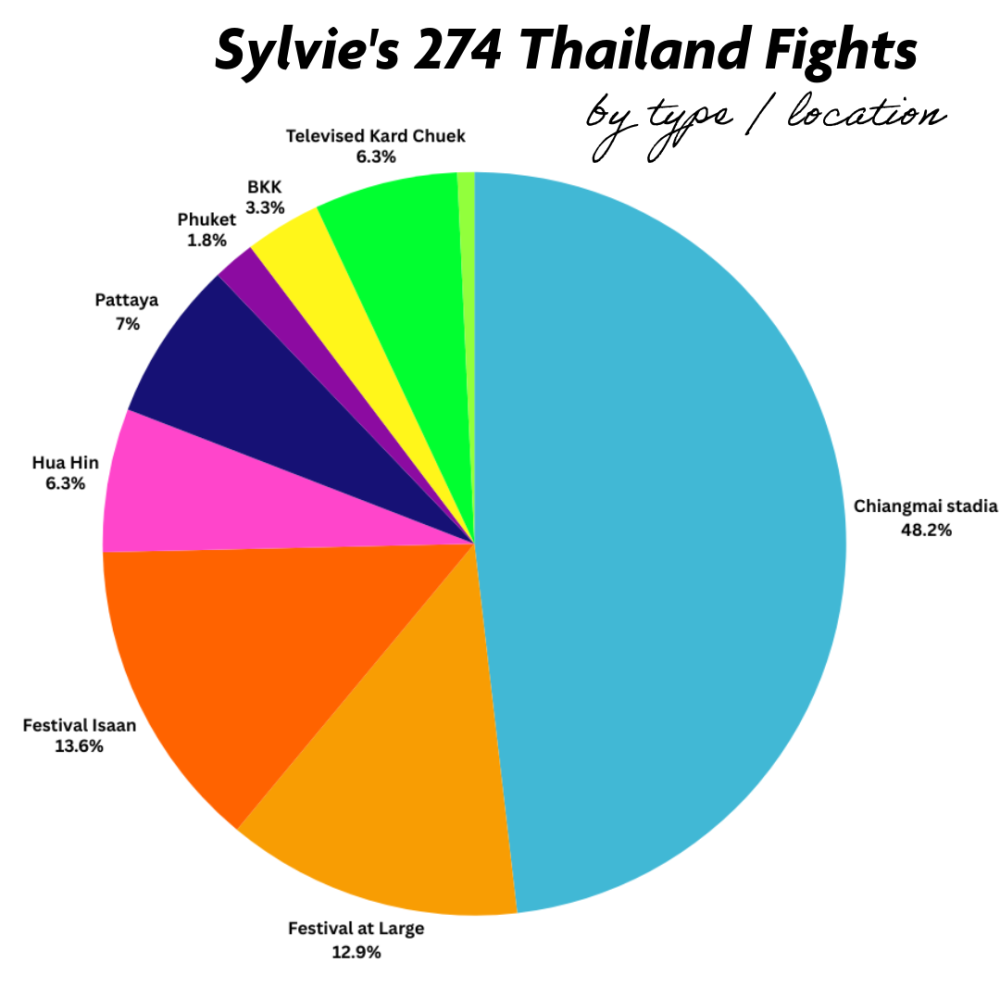

One of the hard things to do is to get scope on what Sylvie has achieved in Muay Thai. The female fighter, of any combat sport, who has fought more documented pro fights than any other in history. You can see video of all of Sylvie's recorded fights here, and her complete fight record here. Because people are often unfamiliar with Thailand's fighting, and some may generalize from their own experience, it seemed good to put together a few percentage distributions of Sylvie's fights. She is likely the most documented female fighter in history, if not fighter of either gender. Sylvie's Fights By Size These weights were often on the scale without weight cutting, the larger weights were either eye-balled or confirmed by asking (there's video of every fight so you can take a look yourself). Everything at 47 or below is Sylvie's weight class. For much of her career she probably was a 44 kg fighter (below the lightest weight class, sub 100 lbs) if she cut. Most fights at 48 kg were already fighting up a bit, though earlier in her career she walked around at 47-48 kg, then in the heart of it (on Keto, etc) she was about 46 kg walking around. In the last year she's spent a lot of time in the weight room and is back between 47-48 kg. Only about 10% of Sylvie's 274 fights in Thailand were properly at her weight. More than 50% of her fights were at least 2 weight classes up, the bulk of those 4 weight classes or higher. She's probably fought up more than any documented fighter in history, other than perhaps Saenchai, who specialized for a long time giving up big weight to non-Thai fighters in Entertainment Muay Thai, and also had a long career of fighting up in the Bangkok Stadia. Sylvie's Fights By Type and Location Sylvie fought a lot of her fights in the Chiang Mai stadia, almost half. At the time it was the best female fighting in all of Thailand because the scene was grounded in Thai vs Thai fighting, not catering to Western fighters. You can read about the scene here, in Sylvie's 2017 article: Why Chiang Mai Has the Best Female Muay Thai Fighting in the World. We haven't been up to Chiang Mai for a long time so we aren't really sure of how it is now, a lot has changed since COVID. Things to note though is that more than a 1/4 of her fights are festival fights, a large number of them in Issan. We found this is the heart of Thailand's fighting style, because festival fights are usually governed by gambling interests (and not set up by a promoter looking to produce paid for content). Thailand is incredibly rich in skilled female fighters, and when you enter the side-bet world that is where matchups tend to be most opponent varied and challenging. Also worth noting, despite Sylvie's resistance to Entertainment Muay Thai (3 round, Westernized rulesets), she has actually fought 17 times in Kard Chuek on television, an Entertainment Knock-out or draw format. The most beautiful thing is that she's fought all over the country, and faced close to 150 different Thai female fighters.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

Race, Class and Privilege - Making History Western women, including White Women, as female Muay Thai fighters, if they are to ascend in a sport respected throughout the world, really need to have this kind of attitude toward Thai female fighters. Much more than even black female basketball players, Thai female fighters made the sport of Thailand's women's Muay Thai - they've been sport fighting in the ring for over 100 years, at least. It is their sport, they excel at it --- even as everyone seeks to change it's rules, Westernize it, as a commodity, there is a certain whitening of the sport. Westerners come into Thailand to train and fight with immense privilege and freedom, joining themselves to a sport and art that already existed whole. Great Thai female fighters need to be lifted up, carried to greater awareness, and supported. Some of this lack of support is the language barrier, some it the exoticization of Thailand, but too many times Thai opponents are just "a Thai" in people's minds. And in the past it has been much worse than that, with racist stereotypes about Thai women and Thailand abounding. Thailand's Muay Thai is in a state wherein, due to Soft Power initiatives as a response to the COVID scare, it is being remade FOR the Westerner, not only as a consumer, but also as a participant (laborer, actually). As the sport tries to lift the prominence of the Western (often White), or generally non-Thai fighter, we just lift the Thai fighter up, across that culture and language barrier.

-

Sylvie's been training with Chatchai 2x a month, and even had her first official Box Rec boxing fight. I've long been fascinated with how inside boxing styles like those Duran had could compliment and complexify Thai clinch, in that they take place in that no-man's-land of 2 ft, where a lot of comboing fighter simply bite down or even close their eyes. These two feet, where inside boxing lives, is often a very undeveloped space in Thailand's Muay Thai, especially these days as fighters have devolved (in part because Western boxing no longer influence the sport as it once did). Duran, Inside Boxing and Clinch above a compilation video made some time ago, on some beautiful Duran teaching arm control and framing up close, and some Muay Thai parallels. Gimyu, Orachunnoi and Samson As mentioned previous Arjan Gimyu who is 80+ hangs out at Rambaa and comments on training. He was a top Thai boxer in his day, fought into his 40s, and was an elite kru of Kaensak and Lakhin and so many others. Among those was Orachunnoi. As Sylvie was boxing sparring and really concentrating on Duran like body attacks he (apparently) came alive, saying how much this was like Orachunnoi back in the day. The fight edit at top flowed out of is comments as sometimes the best way to study someone is to edit their fight. Arjan Gimyu back in the day above, today below: There are lots of fights where Samson uses pressure hands, mixed with Muay Khao clinch, the most memorable perhaps is his defeat of Pepsi after two draws, in the final round, letting go of clinch almost all together, and ripping uppercuts: And his fight vs the great Muay Maat fighter Thongchai, if I recall, featured a lot of boxing to clinch transitions. In the Muay Thai Library Samson teaches his pressure boxing and clinch style. Here is the Thongchai fight, two absolute legends: We even have photos of Arjan Gimyu holding near 80 years of age, for Samson. They must have been Golden Age enemies at point point because Arjan Gimyu was Lakhin's kru when Lakhin and Samson had their famous trilogy of fights, Samson winning 2-1.

-

Teeps Like Samart, Lowkicks Like Wichannoi, Punches Like Samson Above is my little edit of 2x Lumpine Champion Orachunnoi in his fight versus Phetphayao, the first Thai to medal in any Olympic sport (Bronze in Boxing), and thus a National hero. Orachunnoi is famed for fighting up, and looks small vs Phetphayao who some years later would become the WBC Superflyweight World champion in boxing. Phetphayao would be great recognition to Arjan Surat of the Dejrat gym who trained him, his success likely insuring that the gym would be filled with Muay Maat fighters with a boxing influence. Orachunnoi himself was an Asian Amateur Gold medalist in Boxing, and acquitted himself well with lots of inside boxing, and fast hands in this fight. Orachunnoi, Golden Fist and The Poorman's Favorite, was trained by Arjan Gimyu who Sylvie has trained with, in fact my attention was drawn to him in this fight because of Arjan Gimyu. I was pretty moved watching this fight. He's giving up size against a big Thai star, and the way he handles Phetphayao is amazing. His combination of teeps and lowkicks in the early rounds is just so skillful, two weapons that don't often go together, finally giving way to his famed inside boxing. It's a beautiful thing to see Thailand's Muay Thai in such a femeu way melded to boxing in this inside fashion, skills at all distances. The heavy influence of Western Boxing on Thailand's Muay Thai is something that's been occluded by much of the superficial coverage of the sport in English, which imagines Muay Thai as an exotic art cut off from the world. Here you have two really wonderful boxers fighting in full weaponry in Muay Thai. Watching the fight it also saddens me that such a gifted fighter is practically forgotten by English language history. He really has a teep as adept at Samart's, and beautiful hands that do not require distance. Putting the edit together was a powerful aesthetic experience, just enjoying all his timing, his power and suddenness, despite his size. As we've found, small fighters like him were very ill-respected in the 1960s, and it wasn't until the 1970s that they started getting better placement on cards. And like so many great fighters he was forced to fight up, for lack of opponents. Chamuakpet Puts Hims 2nd All Time in his GOAT List You can see Chamuakpet choose his 5 greatest below. This was the first time Orachunnoi registered for us, we had only barely heard the name of this 1970s hero. Watch the fullest video of his fight vs Phetphayao below

-

A Book? I've had several ideas for a book, but a small one comes to mind, I'd like to write. Inner Muay Thai, discussing the "inner" aspects of the art as sport, things that are hard for the West to replicate/imitate, but that are key to understanding and appreciating it. And the reason why most, perhaps unconsciously, are drawn to the sport from around the world, and travel to the country to train and fight. So far, only 3 chapters, so maybe 3 parts. Inner Psychology Inner Space Inner Country Three dimensions of innerness.

-

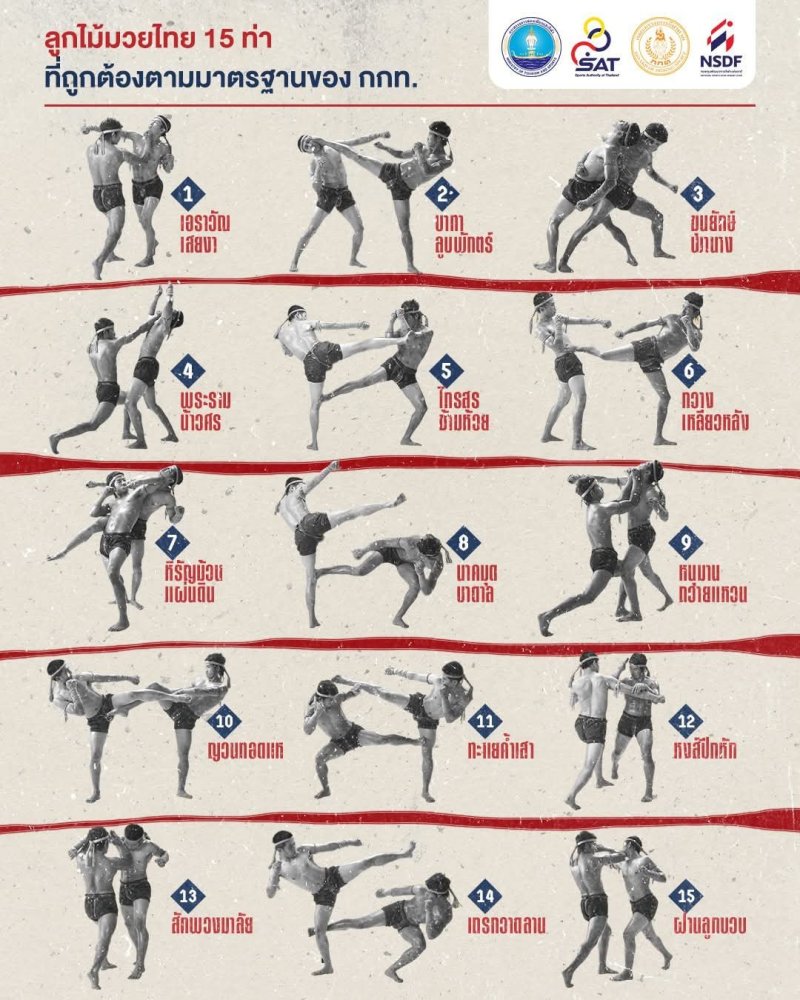

Just dropping this here, the SAT approved Mae Mai (mother wood) Muay Thai (Boran), probably illustrated for some kind of licensing initiative. Not for ring Muay Thai. Noteable is 3, which shows a back of the leg throw showing that before the anti-wrestling and anti-Judo prohibitions, these moves may have been substantive to the art/sport.

-

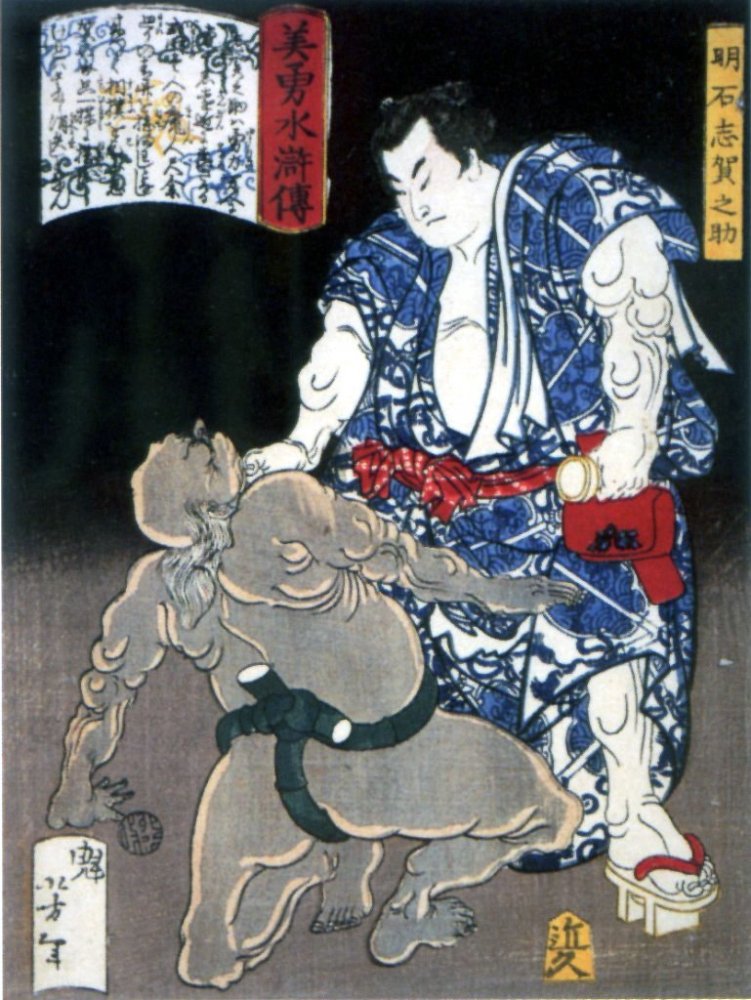

The History of Japanese Sumo and What it Says for Thailand's Muay Thai above Akashi Shiganosuke, the legend of the 1st Yokozuna, perhaps in parallel to Muay Thai's Naikhanomtom Reading today into the history of Japanese Sumo. I've always felt like Sumo could shed an interesting light into aspects of Thailand's Muay Thai, because it is an ideologically intense, rite and tradition framed art/sport, which has resisted acute commercialization and globalization (retained its traditions), but also because it is known for its associations with urban mafia and gambling scandals. Books like: Japanese Sports: A History, Allen Guttmann -- 2001 -- University of Hawaii Press Sumo: from rite to sport, Weatherhill, 1st ed., New York, New York State, 1979 this book I cannot find (maybe its a dissertation?): Boyadjiev, Nickolay T. 1999. Sumo Exposed: The Invention of Tradition in Japan’s National Sport. Boston: Harvard University this book I ordered the paperback The Way of Salt: Sumo and the Culture of Japan Below is a section on Sumo's retraditionalization (invented traditions) from Guttmann's book. Sumo was strongly bonded to Shinto, and became retraditionalized with the rise of Japanese Ultranationalism (also bonded to Shinto). It's affiliation with Shinto aligned Yakuza mafia (like Japanese Kickboxing), put it in particular relationship to Japanese politics. Thailand's Muay Thai has its ideological dimension, with important links to Thai Royalty, and has a limited religious expression (in its relationship to Brahmin ritual and Thai magical rites), but it really lacks that cohesive fusion of politics and religion, in art and sport, that Sumo has, which may explain why nobody is calling for the "natural" evolution of Sumo into a globalized sport, breaking it away from its tradition and meaning (even an re-invented one), while in Muay Thai some are. Because my care for Muay Thai falls along two specific axes: #1 the maintenance of its efficacy which reached its apex in a historical period which is no longer, under social conditions which may not be desirable, #2 the preservation of its meaningfulness, including its cultural instruction upon the nature of violence, it makes sense to think of it in reflection of Japanese Sumo, at least in the sense that both became "modernized" in the 20th century in its engagement with the West, and both anchored themselves in preserved tradition.

-

The Development of Muay Thai in the Siamese Populace An interesting point about the corvee system of labor (established 1518) in the same work, is that it tied the population not only to the land, but also to the proto-state, in terms of movement. This rotation between one's land and state works, which included military service, would ostensibly train an outlying populace in warfare, circulating them back into their villages, so trained. This would work as a dissemination process of martial skills, as returning men themselves could train youth. If indeed (gambled) festival fighting throughout the village networks existed for centuries, developing a practice of inclusion/exclusion, this would account for a steady State driven effulgence that did not require a learning process of actual warfare (though slave labor capture campaigns were regular). It makes an interesting contrasted: a circulating farming populace continually training on rotation, and practicing that training in festival fighting, landed, and a far reaching and mobile non-Thai (Chinese, and others) merchant class, that transversed the region. The landed circulation of corvee work would augment my own thoughts that martial prowess also developed in general raiding patterns outside of the proto-states and their fortified capitals.

-

In the early 20th century there was concern over the "revolutionary" identity shift among Chinese in Phuket. Most of the Chinese had cut off their cues (long, traditional ponytail). Reading now The Crown and the Capitalists: The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai Nation to get a better perspective on Siamese/Thai and Ethnic Chinese relations as they shifted through the decades of the 20th century. During WW2, when Thailand had allied itself with Japan (which had invaded China), there was still fear that China would use its rather vast nationalized Chinese education system (if I understand it right) within Thailand, to possibly turn Thailand into a Chinese colony. Chinese in Thailand were educated AS Chinese, and to some regard taken to be Chinese citizens, even though Thailand considered them Thai. Thailand in this case had a large number of transnational citizenry, whose alliance was not known.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.