Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation since 01/23/2026 in all areas

-

Many are curious or questioning why I’ve become so focused on fighters of the Golden Age, if it might be some form of nostalgia, or a romance of exoticism for what is not now. Truthfully, it is just that of the draw of a mystery, the abiding sense of: How did they do that?, something that built up in me over many years, a mystery increasing over the now hundreds of hours I’ve spent in the presence of Golden Age fighters - both major and minor. Originally it came from just standing in the ring with them, often filming close at hand, and getting that practically synaptic, embodied sense that this is just so different, the feeling you can only get first hand - especially in comparison. You can see it on video, and it is apparent, but when you feel it its just on another order, an order of true mystery. When something moves through the space in a new or alter way it reverberates in you. How is it that these men, really men from a generation or two, move like this. It’s acute in someone like Karuhat, or Wangchannoi, or Hippy, but it is also present in much lessor names you will never know. It’s in all of them, as if its in the water of their Time. I’ve interviewed and broken down all the possible sources of this. It seems pretty clear that it did not come to them out of some form of instruction. It was not dictated or explicitly shown, explained (so when coaches today do these today they are not touching on that vein). It does not seem sufficient to think that it came from just a very wide talent pool, the sheer number of young fighters that were dispersed throughout the country in the 1980s, as if sheer natural selection pulled those movements and skills out. It did not come from sheerly training hard - some notable greats did not train particularly hard, at least by reputation. It’s not coached, its not trained, its not numerical. A true mystery. Fighters would come from the provinces with a fairly substantial number of fights, but at a skill level which they would say isn’t very strong, and within only a few years be creating symphonies in the ring. Karuhat was 16 when he fought his first fight (with zero training) and by 19 was one of the best fighters who ever lived. Sirimongkol accidentally killed an opponent in the provinces (I would guess a medical issue for the opponent, a common strike) and was pulled down to Bangkok because of this sudden "killer" reputation, but he’d tell you that he was completely unskilled and of little experience. Within a few years he was among the very best of his generation. We asked him: Who trained you, who taught you?, expecting some insight into a lineage of knowledge and he told us “Nobody. I learned from watching others.” This runs so hard against the primary Western assumptions of how Knowledge is kept, recorded and passed, but it is a story we heard over and over. Somehow these men, both famous and not, developed keen, beautiful (very precise) movement and acute combat potency without direct transmission or even significant instructional training. The answer could be located nowhere…in no particular place or function. Sherlock Holmes said of a mystery: Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.. All these things that we anticipate make great fighters, these really seem to be the impossible here. They were not the keys, it seems. Instead it appears that it was in the very weave of the culture, and the subcultures of Muay Thai, within the structures of the kaimuay experiences, in the richly embedded knowledges of everyone in the game, in the states of relaxation of the aesthetics of muay itself, in the practices of play, in the weft of festival fighting, the warp of equipmentless training, in endurance, in the quixotic powers of gambling, the Mother’s Milk of Muay Thai itself, which is a very odd but beautiful thing to conclude. It does pose something of a nostalgia, because many of these cultural and circumstantial elements have changed - some radically altered by a certain modernity, some shifted subtly - so there is a dimension of feeling that we want not to lose all of it, that we might still pull some substantial threads forward into our own future, some of that cultural DNA that made some of the greatest fighters ever what they were. It's not a hope to return to those past states, but a respect for what they (mysteriously) created. As we approximate techniques, copy movements, mechanize styles, coach harder and harder, these are all the things that make up a net through which everything slips out. Instead, this mystery, the how did they become so great, so proficient, so perceptive, so smooth, so electric, so knowing, stands before us, something of a challenge to our own age and time.1 point

-

I am 5’8 155 lbs. pk Saenchai seemed like a gym I would go to after years of training which I have not had. By the time I go to Thailand I will have 6 months of solid training. (About 13 hours a week soon to be 18.) I am visiting Thailand first, and then planning on finding where I want to make my home base after about 6 months. I have little experience in the clinch, but I know that I want to be a heavy clinch and elbow fighter, as watching yodkhunpon inspired me. I have never seen a fighter that made me want to copy them before. Thank you for the reply and all you guys do.1 point

-

Hi, I just started Muay Thai and I want a pair of gloves that will last me more than a year and I could use as a all around glove for training and also sparring for when I like rank up. I am 250 lb, 6'1 so I am a bigger guy and I was thinking getting the Twins Special BGVL3 16 oz gloves? Are these good for what I want or are there better options for a similar/cheaper price?1 point

-

New Film Evidence on Early Modern Muay Thai History The above video edit study of the best fighter in Thailand, Samarn Dilokvilas, is taken from one of the most remarkable film records of early modern Muay Thai. This post contains various treatments & edits of the archive footage, highlighting its aspects. Previously of the early modern period we've primarily had short very clips produced for newsreel, with opponents of unknown skill, edited to present to the foreign eye something exotic and unusual (a playlist of early modern Muay Thai footage here). With newsreels we never really know how much the action has been chosen and constructed, or how distortive that may be. The colonial British regarded Siam as comparatively "uncivilized" and the few glimpses of fight footage feel like they were chosen with that view in mind. They are brief, clashing keyholes into the art, but now read almost like puppet shows for theater goers, from a far away land. There was also a Thai filmed dramatic reenactment of a fight, which for some time was taken as genuine fight footage, the earliest on record. It suffices to say that before this film, our visual evidence for how Thailand's Muay Thai (Muay Boran) in its early modern period was fought was deeply fragmented and full of artifice. You can watch the full archive footage of the Samarn vs Somphong fight for the unofficial title of Best in Thailand, from which my edits are cut (the story of this fight and who the fighters were is further below): this footage originally was published in this longer Thai Film Archive. In this case we have lengthy, if significantly edited, fight footage purporting to cover all the rounds of a fight, as well as the showcase of some bagwork, sparring fight preparation and coverage of the historical context of the fight. And, the two fighters are thought to be two of the very best in Thailand, a showdown of great magnitude. It is far more than a keyhole. We get the sense that we are watching an actual, continuous fight from 1936. It gives us insight into the relationship between Thailand's Muay Thai and Western Boxing. You can see Samarn's Western Boxing influenced bagwork in this short edit, as well as an excerpt from General Tunwakom teaching the "Buffalo Punch" of Muay Khorat, which Samarn includes in his light work: The State of Early Modern Muay Thai and British Boxing Beginning with the first decade of the 1900s Bangkok itself was undergoing powerful modernizing influences, much of which embodied by its relationship with the British Empire. Bangkok was a deeply cosmopolitan, thriving Southeast Asian city. It has been estimated that there were as many 3,000 British serving with the Siam police in 1907. The future King of Siam, HM King Vajiravudh, who would modernize the sport would spend near a decade coming of age in Britain in college and military school (he would be given the honorary rank of General in the British army in 1915 and even thought to fight for the British in WW1). Regular Boran Kard Chuek fights were held at the city pillar (and likely in many other undocumented city locations), but there was no stadium or fixed ring in the city until King Vajiravudh came to the throne and implemented Western Boxing's influence. It was a gambling sport of the people whose gloveless, violent nature would ruffle British sensibilities. At a time when colonial powers were using the excuse of beneficently civilizing peoples of Siam's bordering countries as their governance was taken control of, British sensibilities did matter. When prince Vajiravudh's father, the famed King Chulalongkorn, formalized the three regional Schools of Muay Boran (Lopburi, Khorat and Chaiya, bestowing teaching authority to tournament winners) in 1910, he was not founding these styles, but rather consolidating them up (and to some degree secularizing) them as the sport itself was likely beginning to experience change in the face of Bangkok's modernity. This was an act of preservation and commandeering. Through the religious reforms of 1902 outlawing non-Thammayut Buddhism mahanikai practices the National government had begun discouraging customary Muay Thai pedagogies within the wat, moving it away from their magical practices. Fight wicha & magical wicha were likely seen both seen as fighting techniques. The aim was to put more martially trained men under royal auspices and in rationalized contexts. By 1919 British Boxing was taught along side Muay to police and all civil servants at Sulan Kulap Collage. The modernizing, internationalizing art of Judo was also offered. King Vajiravudh, returning to Siam to eventual ascent to the throne saw British sport as key to a society's modernization and Nationalization, and Muay Boran ring fighting was to be shaped to reflect the more rationalized (rule governed, safety concerned) character of British Boxing. The first fixed roped rings in Bangkok (1921, 1923) held both British Boxing fights and Muay Thai fights. you can see a Modernization of Thailand's Muay Thai timeline here It is enough to say that in the Muay Thai of the 1920s a modernization movement was significantly modeled on and inspired by British Boxing, and much of how Muay Thai is today comes from this modernization effort a century ago. But...did this influence change how fighters actually fought in these new rings? And if so, how much? Did Muay Thai/Boran on the one hand adhere to their own characteristics which were purposely counter to Western Boxing, pushing back to maintain its own identity resisting its influence? Or were fighters synthesizing Western Boxing with Muay Boran fighting styles? Was what was happening in the ring a combination, or an uneven example of both? We have so little visual evidence its really hard to say, but this one film (which actually seems to present two fights, more on that further down) is our deepest, most substantive look into the early history of modern Muay Thai as it actually was. My own feeling has been - and I should get that in front - is that while we may prefer to think of Thailand's Muay Thai has possessing its own pure lineage, tracing lines of of styles back even hundreds of years, the true nature of Thailand's Muay Thai is that it is, and has perhaps always been an absorbing art, a synthesizing art, which has taken numerous threads of influence and experience (including international influence) and woven itself into something absolutely unique: an at least 100 year old highly optimized, deeply tested ring fighting art. And substantive to modern Muay Thai has been its dialogue with Western Boxing from its inception in the early 1900s. Not only did British Boxing and Thailand's ring Muay Thai exist side by side in Bangkok, and not only was Muay Boran remodeled on the rules and engagements of British Boxing, but the fighters themselves fought in both sports. The cross-pollination was unavoidable, and probably in some ways quite effectively pursued. The 1936 Fight For Who Was the Best in Thailand: Samarn vs Somphong The fight in question in fact is purported to be for who was the best Muay Thai fighter in Thailand. I think the record is probably a little thin on this, but Alex Tsui provides a very powerful picture of the build up to this fight. Please read his original write up which contains many more details on it here. an excerpt: It was Samarn vs. Somphong III, fought at the Pattani Municipal Government Hall, on 29 April, 1936. Samarn Dilokvilas (career 1926-52), was the grand champion of Siam, from 1933 to 1939, and in those years, he was truly invincible and widely revered as a national hero. His rival, Somphong Vejasidh (career 1930-51) was the most dangerous puncher during the same period, being unbeaten all the way until he captured the 128-pound title at Suan Sanuk arena. A showdown with Samarn was inevitable. Samarn versus Somphong, the most fabulous arch-rivalry in muaythai (then called Siamese boxing in the western media) before the Second World War, enacted a total of six encounters stretching from 1933 to 1939, each a classic in its own right, that captured nation-wide interest and media coverage, in pre-war days of Thailand. Samarn had won the first showdown, an unprecedented ten-round muaythai match at the constitution celebrations, 1933, in what was always remembered by critics as one terrific epical battle. The rematch, in early 1934, was likewise very close, and Somphong managed to clinch a draw, at Suan Sanuk. Thereafter, both went separate ways abroad to campaign in pro boxing, which was a premier spectator sport on the international scene. Samarn fought in Penang and Burma, raking up a record of 9-1, having lost once to Young Tarley, but won the rematch. His last oversea outing was a knockout victory, in four rounds, against George Goudie, lightweight champion of Burma, on 14 October, 1935. Samarn’s ring savvy was so tantalizing that the media in Penang had given him the rather adorable title “Gentleman of Siam”. Somphong’s overseas campaign was just as enviable. A 10-1 record in Singapore (Asia’s most popular boxing hub right up to the 50’s), all against proven pugilists on the international circuit speaks for itself. His last outing was a kayo over Japanese champion Yoshio Natori in four. So, when the two top fighters of the kingdom were set to meet again, for the third time, it was national news, for the question after the two bitter battles had remained to be decided – Which of the two was the best fighter in Siam? So we have two of the best Muay Thai fighters in Thailand, arch rivals, facing off after each has also been a dominant professional boxer in the Southeast Asian boxing circuit. The two fighters embody, one could say, the acme of the sport as it was in relation to its modern inception in dialogue with Western Boxing. They are Muay Thai fighters and boxers. How would they fight? The fight is a remarkable document of the relationship between Western Boxing and Muay Thai in early modern Thailand. It's boxing influence is visibly pronounced. And, there is telltale Muay Boran presence as well. In my film-study edit of the style of Sarman Dilokvilas you can see the boxing footwork, the slips, the jabs, the angle taking, but also the reverse elbows, the throws, the spins, stance switching. It is an amalgam. There are some problems with the footage that I discovered in frame by frame study. The first of course is that it isn't' continuous. It has been edited to capture the "action". And, given the rest of the archive film, and its purpose, this seems likely done by someone who wasn't particularly knowledgeable about fighting (at least by class). This to me means the cut of the film itself probably left out a great deal of the art of fighting, the distance taking, the manipulation of tempo, moments of defense or delay. It presents a very clashy fight. It may have been like that, but editing is a powerful aesthetic tool, and to properly edit a fight take a knowledgeable eye. This is to say, this footage in my view likely suffers some from the same interpretative problems as Newsreel footage. Compounding this problem, the edit itself reuses action sequences, repeating them at different times in the fight, sometimes cutting them into different rounds. I started documenting these by timestamp, but as their number grew I just left it to another day. This just adds to the artificially constructed, and perhaps mis-representational nature of the film, not something that would be immediately apparent. above an example of many repeated action sequences This being said, there is still a lot left on the bone. Lots of techniques and exchange moments. Editing these clash-like exchanges into quick repetitions and a slow motion copy (the video at the top of this post) is to help reveal both their technical nature and to capture their rhythms (removing them from the master, original film edit, whatever it's intention). It seeks to catalogue the fighting techniques of Samarn Dilokvilas, who purportedly was the best Muay Thai fighter in Thailand. How much of a window into the state of 1930's Muay Thai does this fight between Samarn Dilokvilas and Somphong Vejasidh give us? These are both fighters who moved to the professional, international boxing circuit after dominating Thailand's Muay Thai, to great acclaim (mirroring the career patterns of later World Boxing Champions Saensak in the 1970s, Samart, Samson, Weerapol in the 1980s and 90s). They fight with a boxing influence. Sarman on the bag looks like a boxer, again: Did much of Thailand's Muay Thai reflect this? Or was this pocketed knowledge. A small piece of evidence toward understanding this is also found in the archive film. There is another fight in the footage, also edited for action (also with duplicated sequence cuts). It looks like it was a pre-fight show the day before the big fight. You can see that the rope configuration is different, with only two ropes instead of three. So these fighters may very well be important Muay Thai fighters in the Pattani (southern Thailand) scene. While the Sarman vs Somphong fight edit features very little clinch or grappling, this fight as it was edited is almost completely clinch and grappling, peppered with clashing entry strikes. Clinch breaks are still very quick, there is little fighting for position, but we really don't know how much this presentation has been manipulated by the editor of the footage. He might very well have liked to produce a contrast between the two fights, aesthetically, and may have cut out a lot of the art of the fight as boring to non-fight fans. Early Modern Muay Thai and Grappling How much clinch or even grappling (with a possible Judo influence?) was in Thailand's Early Modern Muay Thai is an interesting question. A 1922 Australian news report says that while throws are permitted, clinching is not, while it is unclear how clinch. This possible prelim fight which is filled with grappling-type action is perhaps the best evidence for the role grappling played in some Muay Thai contests in this era. Here is a slow motion edit of those clash entry grappling exchanges, as well as the complete archive footage of the fight: Conclusion What we are left with are two Muay Thai fights, one that features two of the best in Thailand which is quite boxing heavy in style, and the the other a possible prelim fight that is predominately grappling and clash entries. Two very different "Muay Thais". My own suspicion is that Muay Thai in the 1920s-1940s was very eclectic. When the railroads were built in the first decades of the 1900s the diverse knowledge of provincial Muay Thai and its fighting styles were suddenly becoming more connected. Chiang Mai and Lampang fighters could much more readily fight fighters of Pattani and Nakhon si Thammart in the South, or Khorat in Issan. The melting pot of the railroads, nexus'd in Bangkok, but actually in various hubs (this significant fight was in Pattani) must have produced a great influx of new fight knowledge, with styles interacting with styles. It is notable that the symbol of modernization, the train, features prominently in the film, and there are no Thai "wais" in that footage. Everyone is shaking hands proudly in a Western manner. Modernization. If we add in that Bangkok itself, the heart of Thailand's modernization and growing Nationalism, Boxing in part a symbol this internationalizing standard, at first by the King himself and other royal elites, but then systematically within the Thai government, police and civil service. Thailand was encircled by a Southeast Asian professional boxing circuit, born of regional colonialism, in Burma, Singapore, the Philippines, and international boxing surely represented the world standard of fighting within Thailand. It was honorific for Thailand's Muay Thai fighters to succeed in the Southeast Asian circuit, and Thai fighters likely successfully boxed abroad before even the turn of the century. In thinking about the state of Thailand's Muay Thai in the 1930s we must consider these flows of people, from the provinces into Bangkok via railroad, the outward international interaction with the Southeast Asian boxing circuit, and place that Boxing held in the royal and government concept of modernization itself. At this time Muay Thai was rich, eclectic and evolving, full of cross-influences, but also likely held areas of strong resistance, local knowledge bases which preserved and hardened themselves in terms of identity. It was as true mixed martial art ecology of fighting.1 point

-

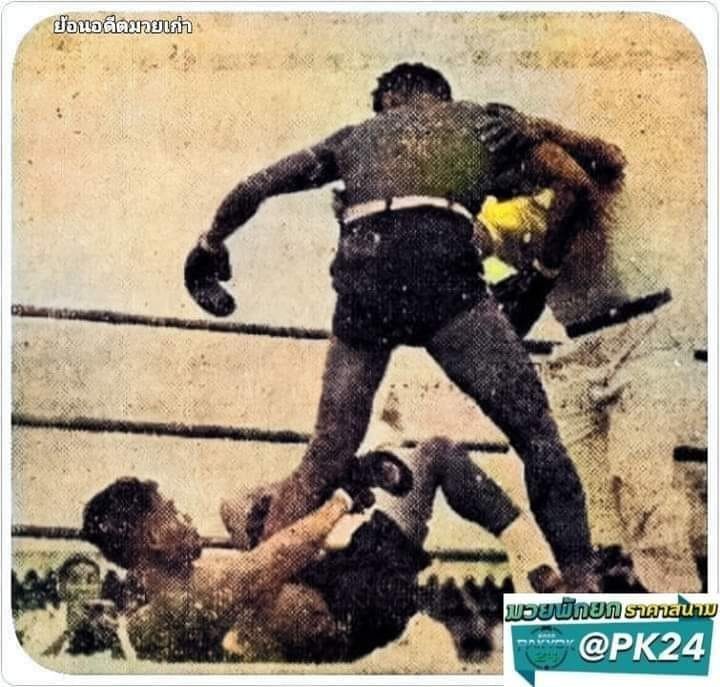

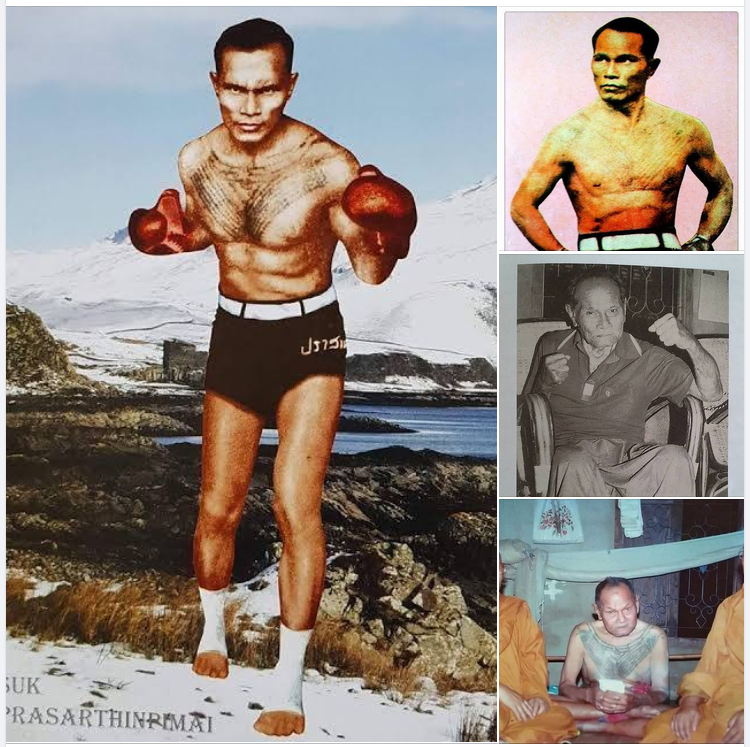

He Returned To The Mongkol A bit of historical context, Somphong who lost vs Samarn above would return to the Muay Thai ring in 1948 to face the feared "Giant Ghost" Suk (grandfather to Sagat), a former imprisoned murderer, who attacked and knocked down Somphong so violently that his corner threw in towel, and it was reported that Suk was boo'd by the crowd for how brutal he was. Suk was a figure of terror in the Muay Thai scene in his day. Historians have pointed out that he was in direct contrast to the more gentlemanly matinee idol starts of Muay Thai and boxing of the 1930-1940s (images of masculine charm and handsomeness persisted through the Golden Age), and was in part promoted by the Fascist regime to move away from reflected composed Royalty, and Royal political power. His transgressive, violent image was a nakleng symbolic of a politics of The People ("Das Volk") as the Phibun dictatorship represented them (it had been aligned philosophically and militarily with Hitler & Japan in WW2). Somphong was nicknamed "atomic fist" (it seems), after the American power that ended the war with Japan. Suk Prasarthinpimai was about 36 years old here, said to have fought into his 40 or even 50s. from this Facebook Post here "ยักษ์ผีโขมด ดวลโหด ซ้ายปรมาณู" วันนี้เมื่อ 76ปีก่อน... วันที่ 16 พ.ค.2491(1948) ศึกชิงยอดมวยไทย ณ สนามกีฬากีฑาสถานแห่งชาติ กรุงเทพมหานคร .."ยักษ์ผีโขมด" สุข ปราสาทหินพิมาย ตำนานยอดมวยไทยผู้ยิ่งใหญ่จากโคราช โชว์โหดถล่มแหลกไล่ถลุง เอาชนะน็อคยก3 "ซ้ายปรมาณู" สมพงษ์ เวชสิทธิ์ นักชกกำปั้นหนักจากเพชรบุรี ดีกรีอดีตแชมป์มวยสากลรุ่นเวลเตอร์เวทและมิดเดิลเวทของประเทศสิงคโปร์ ผู้กลับมาสวมแองเกิลชกมวยไทยอีกครั้ง ...โดยก่อนเกมส์การชกใครๆก็มองว่าสุขจะสู้พลังกำปั้นซ้ายอันหนักหน่วงรุนแรง และความเจนจัดบนสังเวียนของ สมพงษ์ เวชสิทธิ์ ไม่ได้ แต่พอเอาเข้าจริงปรากฎว่า สุข ถล่ม สมพงษ์ อย่างเหี้ยมเกรียม เอาเป็นเอาตาย ไม่มีคำว่าปราณี จนพี่เลี้ยงของสมพงษ์ต้องโยนผ้ายอมแพ้ในยกที่3 ...สุขถึงกับโดนแฟนมวยโห่ หาว่าชกโหดร้ายทารุณเกินไป คิดฆ่าเพื่อนร่วมอาชีพ (ดราม่าเลยว่างั้น) ทำให้ไม่ค่อยมีใครอยากขึ้นชกกับสุข และสุขจึงหาคู่ชกที่เหมาะสมยากมากยิ่งขึ้น ..สุข เผยว่าที่ตนต้องชกแบบนั้นเพราะว่ากลัว ซ้ายปรมาณูของสมพงษ์เหมือนกัน จึงต้องการรีบเผด็จศึกเร็ว ไม่อยากให้ยืดเยื้อ อนึ่งการชกครั้งนี้.. "สุข ปราสาทหินพิมาย" ได้เงินรางวัล 30,00บาท นับว่ามากที่สุดเป็นประวัติการณ์ ในสมัยนั้น พักยก24 : ระบบใหม่ เล่นง่าย ราคาสนาม ออกตัวได้ มีครบทุกความมันส์ (poor) Google Trans: "Giant Ghost, Brutal Duel, Left Atom" Today 76 years ago... Date: 16 May 1948 (1948) Muay Thai Champion At the National Athletic Stadium Bangkok .."Yak Phi Khom" happy at Prasat Hin Phimai The great Muay Thai legend from Korat. Brutal show of destruction and destruction. Defeated by knockout in round 3 "Left Atomic" Sompong Wechasit, a heavy puncher from Phetchaburi. Defeated by knockout in round 3 "Left Atomic" Sompong Wechasit, a heavy puncher from Phetchaburi. แพ้น็อกยกที่ 3 “อะตอมซ้าย” สมปอง เวชสิทธิ์ นักชกหนักจากเพชรบุรี Defeated by knockout in round 3 "Left Atomic" Sompong Wechasit, a hard-fisted fighter from Phetchaburi. แพ้น็อกยกที่ 3 “อะตอมซ้าย” สมปอง เวชสิทธิ์ นักชกหมัดเด็ดจากเพชรบุรี Former welterweight and middleweight boxing champion of Singapore. Who returns to wear the mongkol in Muay Thai again. ...Before the fight game, everyone thought that Suk would fight with the power of his heavy left fist. and Sompong Wechasit's expertise in the ring is not But when it came to reality, it turned out that Suk brutally attacked Sompong. Seriously There is no word of kindness. Until Sompong's mentor had to throw in the towel and surrender in the third round. ...Suk even got booed by boxing fans He said that the punch was too cruel and brutal. Thinking about killing a professional colleague (Drama, that's all) causing not many people to want to fight with Suk. And Suk found it even more difficult to find a suitable fight partner. ..Suk revealed that he had to fight like that because he was afraid. Somphong's atomic left is the same. therefore wanted to quickly put an end to the war I don't want it to drag on. Incidentally, this fight.. "Suk Prasat Hin Phimai" Receive a prize of 30,000 baht It was considered the highest in history at that time. Rest round 24: New system, easy to play, field prices, easy to start, has all the fun.1 point

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.