Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'fighting styles'.

-

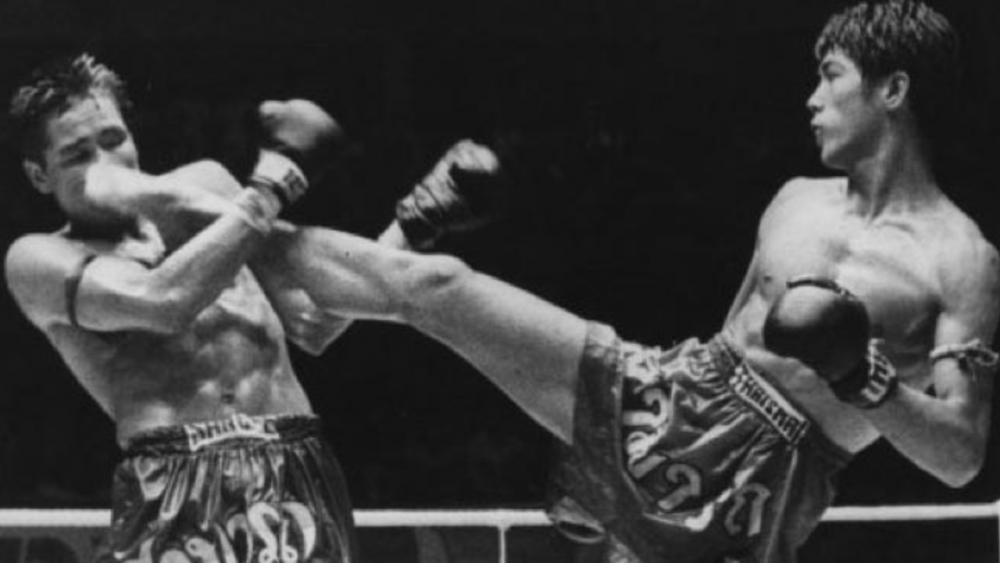

One of the most difficult things when trying to train pretty much anything is that the human organism, in fact all organisms operate with a profound sense of homeostasis. When the system finds its equilibrium it sets its internal thermostat to stay there. The human body regulates its temperature to fall within a certain zone, ideal for its chemical interactions. The alcoholic (just to pick something) stays within the circularity of habits that maintain a symbiotic relationship to the substance alcohol. Each is a system composed of a network or networks that circles back on itself, stabilizing the relations. One may be at the bio-chemical level, the other may involve friends, conversations, work habits, advertisement consumption, diet and many other things (also perhaps reduce-able to bio-chemical chains). How does one change a homeostatically driven system? The first thing to appreciate is that if you have any "bad habits" they are likely part of a homeostatic system. They are part of a sameness, a stability. They aren't just "bad", they are "good" in a set of relations. If you keep dropping your hands in sparring or on the pads, this isn't just an error. It's also something that your body is reading as right or helpful in maintaining itself. If you don't figure out how to replace the "good" that is being done with another, more operative good, it's very hard to convince the system to make the change. In fact, it's pretty much impossible. An example from Sylvie is that we've figured out that she lowers her hands at times in her movement. In particular we were thinking about how she starbursts them when kicking, for instance, instead of being more in guard. They aren't just dropping out of laziness. In fact they are forming part of a balancing mechanism, probably brought on by leanbacks in her kick, when her head moves off of the centerline. Her hands are part of a system of stability. IF you want to stop lowering your hands then you probably need to stop leaning back. You have to teach the whole system a different kind of balance. You can keep yelling at yourself to keep your hands up, but what you are telling the system is: "Don't save yourself." It isn't going to happen. There is a reason they are down. There are probably several reasons, in fact. A single thing like lowering the hands can play a role in several stabilizing systems, physically, mentally, emotionally, etc. But the point is: look to the system. Look to what stability is being accomplished. This is a long way of saying, if you are trying to change one thing you probably need to change the whole thing. Sometimes you can change the whole thing by really pushing hard on the one thing. For instance, you can tie your hands in place, and make it so you can never drop them, and the whole system of balance would be forced to learn another way. That's a brute force approach. It's usually better to globally try and shape the whole system, that way all the connective tissue between parts gets touched. This is one of the reasons play in training is a powerful tool, it pulls more and more into the system, and guides it all to evolve without critical judgment. So, onto the Critical Brain. Some ruminations on the possible nature of the brain and how that might help us see mental (and physical) training under new models. With new models come new expectations and methods. The best article to read on this is the recent Ars Technica Rat brains provide even more evidence our brains operate near tipping point but the quotations in this article are from the Quanta article Brains May Teeter Near Their Tipping Point, Quanta Magazine. Both are summarizing the consequences of a new paper presented on how brains may be structured around criticality. In taking up the idea of training away and through criticality we can see homeostasis in a new way. This theory of the brain suggests that it fluctuates just below criticality, which is in very crude terms like a sandpile. How the Brain is Like a Sandpile The stability of the sandpile system comes from it's inherent instability. What is interesting is how they are very broadly analogizing sandpile avalanches to biological processes, and brain activity like cascading neurons firing to some effect. For instance, waking up. How is it that a sleeping brain moves to becoming awake? What is the process? What is it like? This theory suggests that it's very much like a sandpile. It gets dripped on by grains and slowly moves toward its big avalanche, the cascade of neurons that in unison moves it into a waking state. You can read the articles and see how this may only be a rough analogy, but it's helpful. It's talking about how the organism moves between stabilizing and destabilizing states, and positions itself between. How the Brain is Like an Atomic Bomb The above positions the human brain between thresholds of Noise and dumbness, ever balancing itself in a Goldilocks zone which allows a helpful rate of cascading. I present it here just for digestion. I'm going to veer off on my own tangent. It's my intuition - and I did not read this hypothesis in the literature, and I have no particular reason to think it true - that the way that a cascading, avalanche prone brain dampens its sensitivity (super criticality) is likely that the overall critical system is nested. Which is to say that when a rice grain falls on subsystem x, this grain is released by another, more localized sandpile, if you will. You have hour glasses linked to hour glasses. And at times they cascade all together. At times, in fact many times, the cascade is well below the threshold of consciousness or action. Nested criticality is a very interesting model of development. If we are perusing a physical change, say perhaps snapping back on the jab, or maybe more interestingly developing a quality, let's say being light on your feet, it may be productive to think of this element as a nested subsystem of criticality. Which is to say, we are building sandpiles. Many times we are working on something and it just seems like nothing is happening at all. We are just wasting our time. And, we very well may be. On the other hand, we may be also dropping rice grains with the aim creating a sand pile, which will then critically balance itself with cascades of the desired effect. What is kind of interesting about this is that we tend to look at states in very idealized ways. A good fighter is always calm. A good fighter is always on balance. This fighting style is quick and accurate. But in nested criticality there is no absolute quality. This particular sandpile tends to avalanche, to cascade with this effect, over time. At any one particular moment, a single fall of a rice grain, the system might express that quality, or it may not. If it does not, it isn't failing. It's only a tendency of that subsystem, a tendency to cascade. When we watch someone like Mike Tyson we are struck with significant essentialism. He is just so powerful. He is powerful in all things he does. But it isn't really that way. Many shots aren't powerful. Many shots miss or are miss timed. But then that huge shot lands, accurate, fast, explosive. That's a sandpile avalanching. Lots of grains fell in that fight in which there were only tiny avalanches, and lots fell when there was nothing. Instead of imagining that those were misfires, or failed, perhaps we imagine them as a system near criticality. His training, the state he had developed, was one when power tended to manifest itself. The whole fighter would cascade with a certain effect. The same thing with maybe someone like Samart who is so slick, so on balance. The illusion he creates, often by virtue of great moments in fights when everything avalanches, is that he is ALWAYS this way. He isn't, he's off balance all time, he mistimes things, but he catches himself, the system is tending toward slickness, towards timing. The reason why this is important, or productive, is that it's a way into seeing into the nature of "error" or even unresponsiveness. The failure of a system to produce the desired effect is quickly read in very critical terms. It is broken. It needs fixing. The first thing is to understand that the system, any system, is already not broken. It is operating under a homeostasis already. If the theory of the criticality of the brain is anywhere close to being true, at minimum any particular state a person is in, any habit they have, is part of a pretty delicate and miraculous balancing act of hovering near a tipping point of maximum efficacy. As we try and train that system to have different qualities, we are just moving its tipping points. We do that by addressing nested subsystems and their criticality. The other aspect of criticality and error is that just because the sandpile isn't cascading with the desired effect doesn't mean that it is broken. It just may be that not enough grains of sand have fallen for it to reach criticality. It's just a fairly insensitive pile as yet. Yeah, you flinch still in sparring. Not enough grains have tumbled down. Your eyes and other senses haven't seen enough yet. Yes, you can train bad habits, create sandpiles that cascade in an undesired way, but if you understand that you are building sandpiles in the first place, the role of error or unresponsiveness can be seen in a different way. You are not trying to create a perfect response, as in mechanical views of the world where you push a button, and gears turn, and then the gumball drops out. The same way every time. That is the model we often think of in training. Instead, you are creating sandpiles which tend toward certain effects, certain qualities. And, once you have a pretty good sandpile you are fine tuning its sensitivity to inputs, making it more and more prone towards sensitivity and flow. But, there is no "perfect" state of the sandpile. Even the most revered fighters existed in states where if a single grain fell, nothing would happen. Its only if when enough grains fall, beauty happens.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.

Footer title

This content can be configured within your theme settings in your ACP. You can add any HTML including images, paragraphs and lists.