Child Boxers: Stam and Pet

Also see my Skype Interview with Director Todd Kellstein

Buffalo Girls opens on a shot of the rice fields of rural Thailand. The wet and green of the landscape under sunlight is beautiful, sleepy and feels empty. The scene then cuts to an equally empty boxing ring being swept clean as tables and chairs are set under strings of light. In both shots the quiet spaces alludes to use that is not present, to the hard work of the farmer and the refined bodies of boxers as they move through the ring, throngs of gamblers shouting and gesturing and cheering them on as limbs crash into bodies toward a victorious outcome.

In the case of this film those bodies are of 8-year-old girls, Pet and Stam, who earn an income by fighting Muay Thai in their rural villages in eastern Thailand. Director Todd Kellstein shoots their fights from just outside the ropes, providing a charged view without really allowing the film’s audience to follow the fight itself. And in many ways it doesn’t matter whether it’s clear who’s winning the match because the energy of the clash is a true expression of the fighting itself.

After the initial bout between Pet and Stam a rematch is requested and a 100,000 Baht bet is established (Roughly $3,333 USD). Right away it is evident that this is not Little League or Sunday Soccer for western kids, this is professional Muay Thai fighting; it’s work for the fighters and it’s business for gamblers and trainers.

Stam is tiny. At 8 years old she is 22 kg (48.5 lbs) and through the duration of filming (3 years) she remains 22 kg. To a viewer that is familiar with Muay Thai it is clear when she’s in the ring that she is well trained, strong and has the heart of a fighter. When she’s training she is focused and even toughens up a male teammate when he complains that she’s hitting his stomach too hard during sit-ups – “it’s alright if it hurts!” – and yet she is also very much a child in so many scenes. Her smile covers the width of her face and she erupts in shy giggles as she stands before the camera to speak or makes big eyes and grins in jest as she’s running (doing “roadwork” as boxers refer to it) or doing sit-ups. There is no moment at which Stam’s training or fighting feels out of synch with her being a kid.

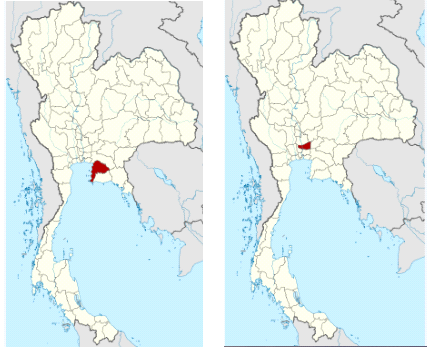

Stam lives and trains in Kleang, Rayong Province at Sor Kon Lek Gym

Several times in the film Stam is the focus when the fight breaks between rounds. Her tiny body is lifted into her corner and plopped down onto a stool as a group of men (her father, her trainers) rub ice and water over her limbs, pour water over her head and face and give instructions from all directions. It’s disorienting, to be sure, but the message gets in. Voices are telling her to “stab in” with her knees, to stop turning in the clinch, to keep turning if she’s already turned, to stop slouching when she counters, that she “must win” and “cannot lose” when the stakes are high. Stam listens and nods, turning her head to acknowledge each of the four or five speakers in turn. This is Muay Thai. I am an adult woman and a westerner besides and this is exactly the experience I have in my corner between every round at every fight. It’s how it’s done and if the focus were on Pet’s corner it would look very similar.

Pet’s face is arresting on film. Without visible eyebrows her very expressive eyes eclipse the youthfulness of her face. Her head is shaved except for two circles on the back of her head where a school girl’s pigtails would be. There she has two pigtails, sometimes braided and sometimes let loose to hang behind her like a lion’s mane. It’s a strange look for a little girl and makes her look a little like a novice monk (whose heads and eyebrows are shaved during their ordination), but it is also less and less androgynous the more you see it. And Pet is not a fan of the style. She explains that when she was little she had a heart condition and was sick all the time. So the monks told her mother to make a deal with the spirits which resulted in this haircut. “I would disappear from the spirits without disappearing from the world,” Pet says. It’s an incredibly beautiful concept and one that many of us outside of Buddhism and Thai anamism/spirits can only partly understand or appreciate. But the sacrifice of Pet’s hair in exchange for her health seems so small and the result makes her anything but invisible.

Pet is from Sri Racha (left), but lives and trains in Pathum (right) at Sitpanamrung gym.

One of the most amazing images of this unique documentary is of Pet running. She keeps a steady and strong pace along a paved road parallel to an open field. The sky above is gray and moving toward sunset, still glowing with light in the clouds while the land itself dims – a great separation of land and sky before the distinction collapses in darkness. Pet is filmed with a slight upshot, her arms and shoulders moving with strength and rhythm like the front of a racehorse and her eyes are fixed on the road in front of her. At her fast pace her cheeks bounce slightly from the impact of each foot on the pavement and her two braids stream and dance behind her like ribbons. The image comes just after Pet, sitting and smiling, says that she believes girls can be boxers, too, “because we are strong,” she says. I don’t know that any fighter, any inspirational video on the internet of athletes with voice-overs about training through pain, has ever inspired me as much as that sequence of Pet’s words, followed by her wordless expression of their truth.

Thailand and Women in Muay Thai

There is a great deal of Thailand that is expressed in Buffalo Girls. On my first viewing I was astounded at how much of my own experiences as a fighter in Thailand (coming from a place that is entirely different from these two girls, socially, economically, culturally, and in my motives) were present in the fighting scenes. I was also struck by how much the complex issue of gender in the world of Muay Thai did not come forward. There are glimpses of gender struggles, all of which revolve around Pet: a few times she is teased (even by her own grandmother) for being mistaken for a boy and when she cries after a loss she is chided with, “boys don’t cry, you know?” And in an interview a referee explains that female Muay Thai is “a hit right now,” to answer why there are “so many” female fighters. These are tantalizing details beneath which perhaps a different story could be told.

At 8 years old, these two fighters weren’t even born yet when women were first allowed into rings in Thailand in 1995. There are still many stadiums in which women are not permitted to fight or even enter the ring, something that Pet and Stam don’t likely encounter fighting in rural Thailand. And at 8 years old Pet and Stam’s gender is not yet pronounced in their bodies or their social roles – although they may experience more of those gender role expectations in school. But at this age the girls don’t seem to notice being female fighters and are more focused on the opportunity and honor of being able to financially help their families. The onus to help financially support the family is in Thai culture, incidentally, placed on female children much more than on male children, but interestingly these girls are accomplishing this through a predominantly masculine means. And doing very well at it: Pet’s parents live almost entirely off her fight earnings when her father cannot work due to injury and Stam’s fight earnings allow her family to finish building their family house. Their age and their gender are both at odds with this kind of income and perhaps it is the uniqueness of being children and girls in the ring that gives rise to the large sum bets which are placed on their fights.

Gambling

Betting is the third major character in this film, without really being directly examined. Gambling on Muay Thai fights is huge in Thailand and from any stadium to any field which serves as a host to a boxing ring you will find large numbers of professional gamblers. My own trainer often tells me, “the gamblers are who truly know Muay Thai; they see you fight and they know more about your fighting, your technique, your strengths and your weaknesses than even your trainers do.” He adds without any hint of jest, “if they come to the corner to give you advice you should listen to it.” Whether attending a night of fights in person or watching on TV you can always see the gamblers, their hands gesturing wildly in the air, signaling fighters to go, screaming for them to kick, clinch, or knee; and when a fighter is winning sometimes you will see them give the stop signal, telling the fighter to hold his position and ride out the rest of the round for a sure victory. The energy is akin to the high-stakes din of the stock market in Hollywood depictions and bookies take bets from every direction and huge sums of money change hands over the course of a night of fights. And the betting is complicated. I’ve asked many people to explain it to me and the westerners who think they have an idea of it admit how limited their knowledge is. In an early scene in Buffalo Girls a bookie – who only takes bets on children’s fights – explains some of the hand signals and how betters can “inject” a fighter with cash promises to encourage or motivate the fighter’s performance. Many times in Stam’s corner, among the group of trainers working on her body and advising her, the gambling takes to the ring as well, echoing through the voices of the throng outside the ropes and through the mouths of her trainers and father as they tell her she’s been “injected” for a few thousand Baht so she must win. The gambling, unlike the crowd itself, is granted access to the ring. I learned more in those two minutes of explanation than I have in two years of asking.

Gambling is what makes this world of children earning income for their families possible. The children do not take part in it, although nearly everyone else does, including trainers, parents, grandmothers, etc. When asked if her rematch with Pet is a betting fight, Stam answers that she doesn’t know – that’s the adults’ business. But this does not mean that the children are unaware of betting or its importance. Even while preparing for sparring during a training session, Stam’s training partner – an equally tiny young boy – teases her that she’s “going to get it and then [her] price will go down.” If I understand it correctly, the boy is implying that if Stam looks as though she’s losing she will become a “long shot” and the price for betting on her will go down, as the underdog. The kid is not using terminology that he doesn’t understand – he knows exactly what he’s saying and what it means.

Way of Life

The scene with her boy training partner concludes with Stam sitting outside to complete her sit-ups while her family watches a TV program inside the house. She laments she wants to watch also. It illustrates in a beautiful, quiet manner the overarching message that I took from the film. The same message was expressed in an answer to the question posed to Stam’s father, himself an ex-fighter, of how long she would keep fighting. He says that if her body holds up she can keep fighting but that in the future when she gets older she can choose for herself if she wants to continue, she can choose her own way. Then he pauses before speaking the words that, to me, in their simplicity explain all of what the film reveals, that Muay Thai is a “way of life.” The expression on his face when he says them – open, flat, matter of fact, at peace – as someone who has lived them, is remarkable.

Surely some western viewers will take issue with watching children fight in a ring, just as some may view the notion of children working to support their families with disfavor – the girls do attend school, to be clear. I’m an adult woman, who makes my own choices, and I am often offered the unasked for opinion that “women shouldn’t fight,” for much the same reason that children shouldn’t fight: because we are fragile. When interviewing director Todd Kellstein (below) BYOD interviewer Ondi Timoner responds as a mother of an 8-year-old boy to the physical violence and emotional pressure of the girls’ Muay Thai fight scene with near revulsion to such treatment of what she calls “fragile beings.” Kellstein’s answer is not simply of disagreement, but of clarification: “that’s an interesting way to put it: ‘fragile beings.’ No, these kids are really really tough; they train six days a week and workout more than you can possibly imagine, so they’re not fragile beings. These are really tough kids.”

Todd Kellstein Interview for BYOD

Kellstein spent three years shooting this documentary and saw countless hours of these girls training. He includes in the film questions to the parents about whether they worry if their daughters will be hurt and both mothers reply firmly that they know how hard their daughters train and so they do not worry. I spend seven hours a day, six days per week training. No, neither I, nor Pet, nor Stam are fragile. There is no question that the work of a farmer is hard; there is no discussion of whether or not it is emotionally difficult to live in poverty; and children are not excluded from work or hardship within the struggles and realities of their families. Buffalo Girls is not a story about breaking under the yokes of these hardships but about finding freedoms within the limits of possibility. Maybe in the future there will be choices for another way, but for the Buffalo Girls and the 30,000 child fighters of Thailand, Muay Thai is a way of life. I encourage everyone to see this film.

Buffalo Girls opens in NYC at the IFC Center (323 Sixth Avenue at West Third Street | (212) 924-7771) on Wednesday, November 14th;

Shadowbox Film Festival at the SVA Theater (333 W. 23rd Street) on Friday, November 30th: 9:00 pm;

Laemmle’s NOHO 7 (5240 Lankershim Blvd., North Hollywood, CA 91601) from Friday, December 7th through the 14th.

I’m checking with the people at Buffalo Girls to see what the future viewing of the film looks like, after it has opened in New York and California. I’ll provide whatever information I get once I hear back. Hopefully it will be available online for widest distribution and viewership.

Visit the Buffalo Girls website and Facebook Fan Page

Official Trailer